A

COMPLETE SET OF FINGERPRINTS

An Annotated

Checklist of the Fingerprint

Mystery

Series published

by

Ziff-Davis,

by Bill Pronzini,

Victor Berch & Steve Lewis

Ziff-Davis was a Chicago-based company that seems to

have formally set up shop in 1935, according to John Tebbel, A History of Book Publishing in the United

States, primarily as a magazine publisher. Besides

periodicals on new hobby activities such as radio and aviation,

Ziff-Davis was also heavy into photography, publishing both magazines

on the subject

(Popular Photography) and by

1939, hardcover books such as Flash

Photography and Composition

for the Amateur.

In 1941, when Ziff-Davis moved to new quarters on the seventh floor of

the

Michigan Square Building, the company’s publications were reported to

have been Flying and Popular Aviation, Popular Photography, Radio News and All Wave Radio, and the Ziff-Davis

fiction group.

The owners of Ziff-Davis were William Bernard Ziff (1898-1953), who is

buried in Arlington National Cemetery, and Bernard G. Davis

(1906-1972), who died in Korea and was cremated there. In 1942,

when the

company merged with the Alliance Book Corporation, based in New York,

William Ziff is

stated as being the chairman of the board, with B. G. Davis as the vice

president and editorial director. (Of significance to mystery and

detective fans is the fact that when the latter left the company in

1958 to form his own company, Davis Publications, one of the magazines

he purchased from Mercury Press and published for many years was Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine.)

Pulp collectors in particular have good reason to be

familiar with the name Ziff-Davis. The fiction magazines

Z-D published in the 1940s

included Mammoth

Detective, Mammoth Mystery,

Mammoth Western, South Sea Stories, Amazing Stories

and Fantastic Adventures.

And not so incidentally, the word “mammoth” should

be taken literally. Before the wartime paper shortages kicked in,

their pulps were huge chunks of magazine, verging on an inch thick.

In 1942 the Ziff-Davis hardcover line of books had

expanded

to cover sports (table tennis, baseball, bowling and so on). It

was not until 1943 that the company began to branch out into other

fare,

which included for the first time mystery fiction, taking over

Alliance’s already existing line of Fingerprint Mysteries. For

Ziff-Davis, Amelia Reynolds Long’s The

Triple Cross Mystery and

Phyllis A. Whitney’s Red Is for

Murder were published on the same day in October of that

year. (The primary focus of this checklist are the books and

authors Ziff-Davis series of Fingerprints. For information on the

earlier Alliance

books, of which there were four, follow the link to a separate section

at the end of this page.)

Starting a new line of books right in the middle of

World War II must have proven to have been quite a challenge.

Books in the Fingerprint line appeared only sporadically until late

1946, which was well after the hostilities had ceased. Thirteen

books

appeared in 1947, but Ziff-Davis had published only five in 1948 before

they closed up their mystery

line for good in the middle of that year, deciding to concentrate on

what the company did best:

non-fiction and their stable of magazines.

Poor distribution was the most likely culprit, with

disappointing sales the result. While somewhat uneven in quality,

the mysteries themselves were generally as good as those of nearly

every other publisher, and in some cases better. They paid higher

advances, thus persuading a number of well-known authors to shift

to Ziff-Davis for financial reasons: Virginia Rath for her last two

novels and D. B. Olsen for a pair. Brett Halliday and Bruno

Fischer joined the Fingerprint Mystery list with the same rationale,

but in

the end the moves proved not to be successful. Except

for Rath, most of them either returned to their original publisher or

found new ones. FOOTNOTE. FOOTNOTE.

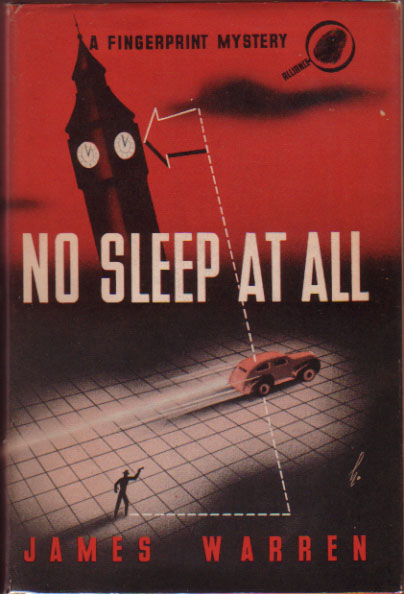

Ziff-Davis had

one primary logo which appeared on the spine of all of their books and

usually on the spines of the jackets as well.

This basic one consisted of a flying horse encircled by the company’s

name. If it appeared elsewhere, it was usually in a

linear design. The additional

logo that appeared on the books in the Fingerprint series was a

fingerprint inside a

stylized

magnifying glass. Surprisingly enough, this eye-catching design

appeared only on the back covers, never the front. Examples of

all these should be

visable in the images seen to the left. The words “A Fingerprint

Mystery”

appear on the front flap under the title on most, though not all of

them.

The books below are presented first alphabetically

by author, and

then for each author in order of publication. The second

listing

is a

chronological one, in overall order of publication. Jacket covers

included for all of the books.

We thank Al Hubin for his help

on the biographical notes for the authors whenever needed.

Steve’s daughter, Sarah Johnson, was also of assistance in tracking

down information on Milton K. Ozaki. Of great service to us once

again was Jeff Falco, who made several suggestions of considerable

importance in regards to the Ziff-Davis story, and we are in his debt

for doing so. Any remaining errors of fact or interpretation are

wholly ours, however.

In all likelihood, as more research is done, the

information on

this page will change accordingly. There will be revisions,

additions,

and perhaps even corrections. Please keep that in mind and return

to

this page every so often for the latest information as to what we know

then about whom.

FOOTNOTE.

We’ve learned a bit more, but not enough to do more than make some

conjectures. Sometime in 1946 through 1947, coincident with the

marked increase in publication of the Fingerprint books, author Clayton

Rawson took over as the mystery editor. Bruno Fischer was already

an early and regular contributor to the Z-D line of pulp magazines, but

based on the fact that the two were personal friends, we believe that

Rawson had a large hand in getting his work published in the

Fingerprint line. (Also note that Fischer’s first Ziff-Davis

hardcover, The Pigskin Bag,

appeared first in the November 1946 issue of Mammoth Detective, and his second, More Deaths Than One was the lead

story in the June 1947 issue of Mammoth

Mystery.)

Rawson

was also probably responsible for Dave Dresser (Brett Halliday) coming

over to Ziff-Davis for the three books he did with them, as once again,

the latter was friends with both Fischer and Rawson. (Halliday’s Counterfeit Wife first appeared in

in the June 1947 issue of Mammoth

Detective.)

Our earlier statement was that higher advances were the reason a number

of authors switched to Ziff-Davis from other publishers. We can’t

confirm that Clayton Rawson was responsible for this, but we suspect

that he was. Another factor entering into our thinking is that

all three, Rawson, Dresser and Fischer, had a hand in the formation of

the Mystery Writers of America (MWA).

From

an MWA

web page,

in describing the history of the organization, Lawrence Treat is quoted

as saying: “A publisher, Ziff-Davis, signed our model

contract and writers flocked to the Z-D banner, which waved for a

couple of years until Z-D gave up its mystery line, for reasons I don't

know, but which may have had something to do with breaking the solid

front of publishers, who would neither sign our model contract nor even

think about our share-the-rental program, because it involved (perish

the thought) some bookkeeping.”

Another website

describes the contract in more details as follows: “Mysteries at the time were sold at a standard, set in stone,

price of $2.00, and were sold primarily to rental libraries. Such

a book could bring in more than $10.00 for the store, but the writer

would never see more than twenty cents in royalty payments. The

MWA pushed a revolutionary idea of raising the price of the books to

$2.50, and splitting the fifty cent increase between the author and

publisher. They even put together a model contract that would

give the author a fairer share of the subsidiary rights.

Ziff-Davis

signed the model contract, and enjoyed flocks of mystery writers

rallying around them until they discontinued their mystery line.

No

other publishers would touch the model contract or the MWA’s ideas

about sharing in the rental profits.”

RICHARD

BURKE

The Red Gate

|

1947

|

|

Sinister Street

|

1948

|

Quinny Hite

|

Over a relatively short writing career, Richard

Burke had ten mystery novels appear from six

different publishers between 1940 and 1948. This pair of

Fingerprint Mysteries from

Ziff-Davis were the last two he did, although he lived until

1962. Five of the ten books featured a Broadway private

detective

named Quinny Hite, an ex-cop noted for wearing a derby while on the

job. His final appearance was in Sinister

Street.

Of note is the first case that Hite solved,

The Dead Take No Bows

(Houghton

Mifflin, 1941), which was the basis for DRESSED

TO KILL, one of a series of Michael Shayne movies that starred

Lloyd Nolan in the 1940s. Lightning

did not strike twice, however, and nothing else that Burke wrote was

picked up by Hollywood.

The Red Gate is one of those tales

where a young girl from a poor background marries an old guy (rich) and

when the old guy (a

judge) dies, the young girl gets the blame. Clumsily plotted,

says the review in the The New York

Times, while conceding at the same time that Sadie has some

charm. The book itself is dedicated to “Helen and Dave,” whom we

presume to be Helen McCloy and Davis Dresser, aka Brett Halliday.

According to his obituary,

Burke died on the job as a typesetter for the Santa Barbara News Press at the age

of 76, having worked for more than 60 newspapers over the years.

The information on the dust jacket refers to him as having been on the

staff of the Daily Times in

Santa Maria, California, for many years, a theatrical photographer, a

Shakespearean actor and a world traveler.

HELEN

FARRAR

Murder Goes to School

1948

Herself

a schoolteacher, Helen Farrar’s only mystery novel also had an academic

setting. College and university settings are quite common in

detective fiction, but not so high schools, which is where Farrar’s

leading character, Sherry Cornell, finds herself in the

middle of a murder case.

Sharing the detective work with

Cornell, a language instructor at Los Lomas High School, is the local

county sheriff, Jim Ericksen. Bill’s judgment is that the book is

a good one, and that Cornell and Ericksen made an excellent sleuthing

team together. Regrettably, such a series never happened, as a

second book from Helen Farrar was never written or published.

According to the dust jacket, the

author was the daughter of a university professor, educated at the

University of California, studied at Oxford, Cambridge, and the

Sorbonne, and taught English, French, and history in half a dozen

schools and junior colleges, mainly in California where the novel is

set.

She is also not to be confused, as

we were for a short while, with Helen Graham Farrar, who wrote two

gothic novels in the early 1970s.

BRUNO

FISCHER

The Pigskin Bag

|

1946

|

|

More Deaths Than One

|

1947

|

PI Ben Helm

|

The Bleeding Scissors

|

1948

|

|

Before turning to writing

for the pulp magazines in 1936, Bruno Fischer, born in Germany in 1908,

held a

variety of other jobs after high school: he was a sports reporter,

rewrite man and police reporter for a Long Island newspaper, he was a

truck driver and chauffeur, and he did book reviews and political

columns for New Republic and

other similar magazines. FOOTNOTE

Once established in the pulp field, however, Fischer

became a full-time writer, producing hundreds of mystery, detective,

and weird menace stories for just about every magazine under the sun,

using both his own name and the pseudonymous Russell Gray.

Fischer’s first hardcover mystery novel, So Much Blood, was published by

Greystone Press in 1939. His primary series character,

medium-boiled private eye Ben Helm, first appeared in The Dead Men Grin (McKay,

1945). Helm, who was married and was perhaps as much a

criminologist as he was a PI, ended up in a total of six mystery

adventures in hardcover before he was through.

Fischer left the pulps and hardcover fiction behind

in the early 1950s, and much of his reputation among collectors today

rests on the large number of original crime novels he began doing then

for Gold Medal. After 1969 he gave up writing to assume the

positions of executive editor of Macmillan's Collier Books and

education editor of the Arco Publishing Company, both of which he held

for over a decade.

As for Fischer’s books in the Fingerprint series, The Pigskin Bag is a finely crafted

suspense novel about a man who finds the eponymous bag in his garage,

it having belonged to a man who died in an accident witnessed by his

wife. Before he can take the bag to the police, it is stolen and

a murdered man left in its place in the garage. Reviews were

uniformly excellent. Will Cuppy in the Saturday Review, for example,

called it “exciting, fast-moving, with some spine-tingling moments.”

The Bleeding

Scissors is another suspense novel, this one involving a man

whose wife suddenly and inexplicably turns up missing, a New York City

play called The Virgin Mistress,

an apparent hit-and-run death, and a villainous private detective

(not “Nameless”).

More Deaths Than

One, the middle entry among Fischer’s Ziff-Davis mysteries, is

Bill’s own favorite among the three. This one is an unusual

detective story told in alternating first-person viewpoints among six

principal characters, one of whom is Ben Helm, and another one of whom

is the cleverly and fairly concealed murderer of a womanizing artist in

a small upstate New York town.

Fischer was particularly good at drawing believable

characters whose actions and motivations are psychologically sound, an

ability he demonstrated to good advantage in More Deaths Than One, and equally

so in The Evil Days, his

final work of crime fiction (Random House, 1974). Failing

eyesight regrettably prevented Fischer from doing others, as he had

planned. He died in 1992.

FOOTNOTE.

The entire Fischer family emigrated to the US in 1913.

R. L. GOLDMAN

R. L. GOLDMAN

The Purple Shells

1947

Raymond Leslie Goldman,

to use the author’s full name, was born in 1895 and is said to have

taught creative writing in Nashville after serving in World War

I. His writing career began in the pulps and the occasional

slick magazine, his first published story

being “Smell of Sawdust,” which appeared in Collier’s Weekly in 1917.

Leaving the pulp magazines after the 1920s, Goldman became a regular

contributor of stories and articles to the Saturday Evening Post, Pictorial Review, Delineator et al.

His first mystery novel, the hard-to-find The Hartwell Case (Skeffington,

1929) was published only in England, as was his second, The Murder of Harvey Blake

(Skeffington, 1931). A quote from the jacket of the latter

suggests that: “As in The Hartwell

Case, even the most enthusiastic amateur detective reader will

prove unable to probe the mystery surrounding the murder, though the

author distributes his clues with a lavish hand.”

This second book is also notable for the first

appearance of Goldman’s long-running

series characters, newspaper editor Asaph Clume and his “irrepressible

red-headed reporter” Rufus Reed. Clume and Reed

appeared together in six detective

novels, including four published by Coward-McCann (1938-42). The

final one, and Goldman’s last mystery, was The Purple Shells for

Ziff-Davis.

Reed, who is the narrator, is also the

principal

character, although Clume also has a role. Set in a

fictional midwestern town, the story involves the murder of a biology

professor, strangely found with purple sea shells lying beside

him. It may be one of the few conchologist mystery novels in

existence. Bill calls the book well-written, as he deems all

of Goldman’s work.

FOOTNOTE:

Three

of Goldman’s stories were the basis for cinematic productions. BING BANG BOOM (1922) was

adapted from the serial novel of the same name in Argosy All-Story Weekly, July 31 -

August 28, 1920. BATTLING

BUNYAN (1925) was based on his story Battling Bunyan Ceases to Be Funny,

which appeared in Saturday Evening

Post, March 15, 1924. The source story for the two-reeler THAT

RED-HEADED HUSSY (1929) has not yet been identified.

FOOTNOTE:

Most of Goldman’s novels appeared as by R. L. Goldman. Not all,

however. His last Coward-McCann mystery, Murder Behind the Mike, has the

full Raymond Leslie Goldman byline everywhere on book and jacket except

for the spines, which have it R. L. Goldman in both cases. On The Purple Shells, the byline is R.

L . Goldman on the jacket cover but Raymond Leslie Goldman on the front

flap, and on the title and copyright pages of the book. Don’t you

just love writer and publisher consistency?

BILL GOODE

The

Senator’s Nude

1947

The author of only the

one mystery novel you see to the left, Bill Goode was the pen name of

William F. Goodykoontz (1914-1990), at one time a reporter for the Washington Daily News, for which he

wrote a regular police and courts beat column called “It Happened in

Washington.” He later switched from crime to political reporting,

covering the White House and the House of Representatives for various

news sources, including the Washington

Post.

Perhaps you can tell from the front cover of the

dust jacket (seen to the left) that The

Senator’s Nude was not intended to be an Advise and Consent type of

novel. More from the blurb on the inside flap:

“Headlines throughout the nation rock Washington

society when they tell the world: NUDE GIRL FOUND MURDERED IN SENATOR

SMUDGE’S BED! You’ll rock too – with laughter – as the Senator

protests frantically that he has never seen the girl before ...

“Bill Goode’s uproarious mystery novel gives you

suspense until the last page, detection at high speed, laughs in every

lethal line, and introduces you to a new and scintillating team of

detectives – Stoney Hawk, a night editor with a remarkable nose for

news, and Larry C. King, who by emulating Casanova, helps solve the

year’s most hilarious homicide.”

Not the Larry King we all know and adore today, we

presume.

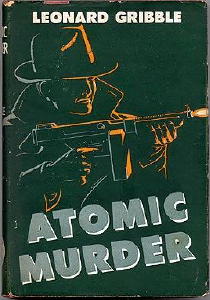

LEONARD GRIBBLE

Atomic Murder

1947

If there were a ringer

among the list of mysteries Ziff and Davis did in their Fingerprint

line, this is the one that it would be. It is, for example, the

only book written by a British author, and the only one reprinted from

a prior publication. Why they happened to choose this one is a

... mystery.

All of the other books in the series are solid

Americana, pure and simple. Take a quick run through all of the

authors and all of their books, and you will see what we mean.

Nor was Gribble especially well-known in this

country. Of the fifty or so published under his own name, in a

career spanning from 1929 to 1986, only a small fraction have ever been

published in this country, and many of those came later on, in the

1950s. FOOTNOTE

This is not meant to diminish Gribble’s

accomplishments or his abilities. His long-running series

character, Scotland Yard’s Supt. Anthony Slade (who also appears in Atomic Murder) must have been

popular in England, but as John Creasey also discovered for a long

period of time during the 1940s and 50s, being popular in England does

not mean that it carries well over here in the US. One source on

the Internet describes Slade as being described elsewhere as an

“imaginative but cautious”

policeman.

A review in the New

York Times was less encouraging, however. Describing the

plot as one in which Slade must investigate the machine gun slaying of

the prime mover behind a project to harness nuclear energy for

industrial use, the reviewer went on to say, “It is quite possible that

the reader will weary of it all before Slade gets his man.”

No matter what, it also means that Atomic Murder is also the only

definitive police procedural in the Fingerprint series, qualifying it a

second time over for its outlier status.

FOOTNOTE.

Here is a list of the other names that Gribble wrote mysteries under

over the course of his career: Sterry Browning, James Gannett,

Leo Grex, Louis Grey, Piers Marlowe, Dexter Muir and Bruce

Sanders.

BRETT HALLIDAY

Series character: private eye Michael Shayne in all titles.

Blood on Biscayne Bay

|

1946

|

|

Counterfeit Wife

|

1947

|

|

Michael Shayne’s Triple Mystery

|

1948

|

Contents:

Dead Man’s Diary (Black Mask,

September 1945)

Dinner at Dupre’s (Mystery Book Magazine, September

1946)

A Taste for Cognac (Black Mask, November 1944) |

Among author Davis Dresser’s other pseudonyms

were Asa Baker, Matthew Blood, Hal Debrett (with Kathleen Rollins

Dresser) and Anderson Wayne, but it was as “Brett Halliday” that he

made both his fame and fortune. Never a prolific writer for the

pulp magazines, in spite of the collection of three novelettes that

made up the Triple Mystery

collection, both Brett Halliday and Mike Shayne first started to appear

in book form very early on.

The first Halliday-Shayne combo was Dividend on Death (Henry Holt,

1939). After four more books for Holt, the Mike Shayne

books switched to Dodd, Mead & Co., where he stayed for most of the

rest of his hardcover career, a run interrupted only by the short stay

with Ziff-Davis before returning to the folks at Dodd, Mead.

Beginning in 1965, however, the adventures of Mike Shayne began to

appear as paperback originals from Dell, where his books had been

reprinted almost from the beginning.

Also worthy of note is that even before the change

to the paperback originals, Dresser had begun to farm out the Mike

Shayne franchise to two other writers, Ryerson Johnson and Robert

Terrall.

For a short while toward the beginning of the series

Mike Shayne’s adventures took place in New Orleans (as did the stories

that were part of the 1948 radio series starring Jeff Chandler), but

the locale with which he will always be associated is Miami. The

cases solved by the tough, red-headed private eye, known for (yes) a

taste for cognac were featured not only in the books and on the radio,

but he was played in seven 1940s B-movies by Lloyd Nolan (there were

twelve in

all) and on television for one season in 1960-61 by Richard Deming.

There was also a Mike Shayne comic book, and of

course his adventures continued for many years after the books ended in

a mystery magazine named after him. Few of these later stories

were written by Dresser (as one of the collaborators on this checklist

knows full well) but one thing is certain. Few authors have ever

come up with a character as well known in his time as Davis Dresser

did.

LEONARD

LEE

The

Twisted Mirror 1947

Although Leonard Lee has only

this one entry in Crime Fiction IV,

it hardly seems appropriate to refer to him as a one-shot writer.

Born in 1902 and educated at Princeton, Lee wrote a number of stories

for The Saturday Evening Post

in the 1930s, and in the 1940s he became one of the contributing

authors to the Sherlock Holmes

radio program.

Even more significant is his career as a

screenwriter in Hollywood, including among the films to his credit such

crime entries as DRESSED TO KILL,

with Basil Rathbone and Nigel Bruce starring as Holmes and

Watson; THE FAT MAN, based on

the famed radio series; SPY HUNT,

based on a Victor Canning novel; and THE

GLASS WEB, based on the Max Ehrlich novel.

Lee eventually moved to television, working on such

series as 77 Sunset Strip and

Border Patrol before his

death in 1964.

While The Twisted

Mirror is his only novel, a play, Sweet Poison, was performed in 1948

and was the basis for two made-for-TV movies, once in 1959 under Lee’s

title, and again in 1970 as Along

Came a Spider.

Mirror is

a suspense novel in which a series of murders begins to happen in a

small California town, and it is up to Lt. Gregory and his men to stop

the killer responsible. The actual protagonist, however, is the

narrator,

newspaper editor Steve Ross. A pretty good novel, in Bill’s

judgement, tense, with the climactic scenes in a fogbound amusement

park especially well done.

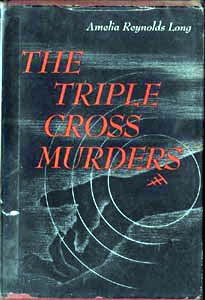

AMELIA

REYNOLDS LONG

The Triple

Cross Murders

|

1943

|

Edward

Trelawney

|

Death

Looks Down

|

1944

|

Edward

Trelawney & Katherine “Peter” Piper |

Symphony in Murder

|

1945

|

Edward

Trelawney

|

Before Amelia Reynolds Long began a second career in

writing mysteries, she was a poet and author of many tales of fantasy

and science fiction. One of the few women in the field in the

1930s, she was a steady contributor to magazines such as Weird Tales, Strange Stories, Amazing, and Astounding. After the

publication of The Shakespeare

Murders (Phoenix Press, 1939), however, she became almost

exclusively a writer of hardcover detective fiction. FOOTNOTE (1)

Most of these books also appeared under the Phoenix

imprint, both before and after her stay with Ziff-Davis. Long

eventually became the most prolific contributor for Phoenix, a

publisher of books largely designed for the lending-library

market. In all, she wrote 30 or so mysteries in the period

between 1939 and 1952, both under her own name and as Adrian Reynolds

and Patrick Laing.

Uneven in quality, her books were not well reviewed

at the time. Anthony Boucher, for example, referred to them at

various times as “lightweight” and “filled with cardboard

characters.” The books often seem to feature an ingenious plot

setup, only to be undone by development and explanations seemingly

unable to match the skillfulness in how they are begun.

Long’s books do remain popular, however, and they

continue to be sought out by collectors. Coming more or less at

the height of her mystery-writing career, the ones done for Ziff-Davis

are perhaps as typical as any other of her novels. FOOTNOTE (2)

The Triple Cross

Murders concerns the murder of a well-known surgeon and lecturer

at the Philadelphia University Medical School. A severed hand

with a triple cross tattooed on the wrist, disappearing bodies, an

alleged ghoul, and a character colorfully dubbed Louie the Hop figure

prominently. The case is solved by one of Long’s series

characters, Edward Trelawney, a criminal

psychologist and a special consultant to the D.A.’s office.

Death Looks Down

features murder most foul in the American Literature Room of the

Philadelphia University library, and involves a group of Edgar Allan

Poe scholars, the theft of what is alleged to be the original

manuscript of Poe’s “Ulalume,” a disappearing corpse (a Long staple)

and four gruesome murders. (Another great setup that fizzles

toward the end.) Trelawney is once more on the job, this

time with the assistance of another of Long’s series characters,

mystery writer Peter Piper (female).

In Symphony in

Murder, the

new conductor of the Philadelphia Philharmonic is mysteriously shot

during a performance of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony. Trelawney

again

does the sleuthing.

FOOTNOTE

(1). The Shakespeare

Murders was not quite Amelia Reynolds Long’s first mystery

novel. In 1936 she wrote a book entitled Behind the Evidence, based on the

Lindbergh kidnaping. Published under the pseudonym of Peter

Reynolds by the Visionary Publishing Company, only 75 copies were

printed. Most of these, it is reported, were distributed to

friends of the author.

FOOTNOTE

(2). The one I’ve found to be the most satisfying (Bill

speaking here) is The Leprechaun

Murders, an Adrian Reynolds effort (Phoenix Press, 1950) and

perhaps her least typical – this one because leprechauns, real ones,

figure prominently in the story (!).

A NOTE OF

THANKS: For much more information on Amelia Reynolds Long, we

recommend you to a website

dedicated to her by Richard Simms, who most graciously provided us with

the cover image of The Triple Cross

Murders.

D. B.

OLSEN

Widows Ought to Weep

|

1947

|

|

Cats Have Tall Shadows

|

1948

|

Rachel Murdock |

Besides the mysteries that appeared under her own

name, D(olores) B(irk) Olsen also wrote as Dolores Hitchens, Dolan

Birkley and Noel Burke. She was born in Texas but spent most of

her life

on the West Coast – California, Oregon, Washington. She had two

children by her first husband, a Mr. Olsen whom she shed after a

short marriage.

Her second husband, Bert Hitchens, was a railroad

detective and her collaborator on five railroad mysteries in the

1950s, but we will continue to refer to her as Olsen throughout these

notes. FOOTNOTE

Her first published work was a poem in a motion

picture

magazine when she was 13, and she later won a prize for an

inter-scholastic book of poetry while in college. Olsen’s first

novel, A Clue in the Clay,

was published

by Phoenix Press in 1938, while her second novel, The Cat Saw Murder (Doubleday Crime

Club, 1939), introduced her spinster sleuth, Rachel Murdock, the

heroine of a dozen atmospheric “cat” mysteries. Another series

character, English Literature professor A. Pennyfeather, appears in

five novels.

She did her best work as Dolores Hitchens, producing

several very good suspense novels and two excellent private eye novels

featuring a character named Sader. One of these, Sleep with Slander, Bill considers

the best traditional male private eye mystery by a woman, just edging

out Leigh Brackett’s No Good from a

Corpse.

Olsen was a very versatile writer, experimenting

with several different types of crime fiction over the course of her

career. She even published one first-rate western novel, Night of the Bowstring (Doubleday,

1962), again using her D. B. Olsen byline.

The first of the two books she did for Ziff-Davis, Widows Ought to Weep, is an eerie

blend of suspense, ghostly terror, and sly humor. From the jacket

blurb: “When Mr. Trimble, surburban carline conductor, looked at the

frightened girl ... and then beyond her at the dark and monstrous shape

with the gleaming yellow eyes, he felt a cold shiver run up his back.

And later, when his erudite and fanciful friend, Isaac Puckett,

finds the dead yellow hairs where the thing had been sitting, Mr.

Trimble wishes he had never seen [the girl], and wishes more fervently

that he had never become involved in the mystery about her Uncle

Merlin, eccentric electrical wizard, and his three oddly assorted

ex-wives.”

Cats Have Tall

Shadows is a Rachel Murdock whodunit, set in a hotel on the

Oregon coast and involving an odd assortment of characters, a couple of

murders, and a collection of porcelain cats.

FOOTNOTE.

The first version of this statement referred to Bert

Hitchens as a railroad superintendent. An email from Jim Doherty

corrected us on this point, and he goes on to say: “Specifically,

he was an investigator for the Southern Pacific Railroad Police, which,

coincidentally, was the same department my grandfather, the first

member of my family to go into law enforcement, worked for.

“The five novels she collaborated on with her

husband were police procedurals about a squad of railroad cops in L.

A. Each book put on a different cop or set of cops in the

lead. They’d recede into supporting roles in other books in the

series. Debuting a year before McBain's first 87th Precinct book,

they actually anticipate his concept of a ‘corporate hero.’

“Indeed, they actually carry that concept to fuller

fruition, since, in the 87th Precinct series, Steve Carella very

quickly became ‘first among equals,’ while in the Hitchens’s railroad

police series, no one character ever rose to that level of prominence.

“I’m certainly a big fan of these books. She

was almost unique in being able to switch back and forth between a more

traditional, ‘cozy’ style as Olsen, to a hard-boiled style as Hitchens.”

|

|

MILTON

K. OZAKI

The Cuckoo Clock

|

1946

|

Caldwell & Brinks

|

A Fiend in Need

|

1947

|

Caldwell & Brinks |

Born in Wisconsin in 1913, Milton K. Ozaki’s first

two detective novels were published by Ziff-Davis, the only two

mysteries of his that were published in hardcover. He went on to

be a prolific author of numerous other paperback PI and suspense novels

in the 40s and 50s, but before any of this Ozaki had been at various

times a newspaperman, an artist, a tax accountant and (this is

significant) the owner and operator of the Monsieur Meltoine beauty

salon in the Gold Coast section of Chicago. FOOTNOTE (1)

Fans of obscure fictional private investigators may

recognize Ozaki as the creator of the following medium- to hard-boiled

detectives: Rusty Forbes, Max Keene, and Carl Guard. The latter,

according to www.thrillingdetective.com,

may be only a slight variation of another PI named Carl Good, whose

adventures Ozaki wrote about under his most frequent choice of

pseudonym, Robert O. Saber.

Both of the Fingerprint books, however, were cases

for the sleuthing team of Professor Androcles Caldwell, head of the

psychology department at North University in Chicago, and his Watson,

Bendy Brinks. Lt. Percy Phelan is the representative of the

Chicago police force who appears in both books.

The Cuckoo Clock

takes place in a beauty salon similar to the one Ozaki himself once

owned, as mentioned above, the case itself being of the “locked

room” variety. In the second book, A Fiend in Need, a corpse is found

in the self-service elevator of an apartment house, and all of the

suspects seem to have airtight alibis. FOOTNOTE (2)

The last non-reprint work of mystery fiction

appearing as by either Ozaki or Saber appeared in 1960. In 1973

the former president of the Chicago chapter of the MWA made small

headlines in the Washington Post

and the New York Times in

quite a different way. Having moved to Colorado, Milton K. Ozaki

became the self-named president of all but non-existent Colorado State

Christian College of the Church of the Inner Power, Inc.

Headquartered in a small cabin on an isolated mountain road, the school

offered doctorates in many specializations in exchange for donations of

$100 or more. The New York State Supreme Court took exception to

this scheme.

FOOTNOTE (1): He

was the son of Frank J. and Augusta Ozaki, his father having emigrated

to the US from Japan in 1899, found his way to Kenosha, Wisconsin, and

married Augusta, a native of the state. His father adopted the

name Frank, but his Japanese name was Jingaro (preserved in his middle

initial J. Even though he was the product of a mixed marriage, we

believe that Milton K. Ozaki is among the earliest mystery writers of

Japanese heritage writing in English as his (or her) primary language.

FOOTNOTE (2):

Fourteen years after her father’s death in 1989, Gaila Ozaki Perran,

took the plot of The Cuckoo Clock

and rewrote the

story as Ticked Off!

(Authorhouse, 2003, trade paperback), modernizing it and changing the

locale

from Chicago to upscale Westport, Connecticut. The downtown

beauty salon is still present, as is Lt. Phelan, but the two amateur

sleuths are now Professor Sanford, of Fairfield University, and his

assistant, David Trent.

The locked room aspect is described thusly: “The

owner of the [...] salon is found dead in his apartment, with a knife

wound in his back. The knife, wiped clean, is on the table beside

him. Every door and window is locked from the inside and there

are no fingerprints anywhere.”

NOTE:

For an overall look at the Ozaki oeuvre,

you cannot do better than Bill Crider’s in-depth investigation of his

work, complete with checklist and cover photos.

HUGH PENTECOST

Memory

of Murder 1947 Four

short novels. Series character: Dr. John Smith.

● Fear Unlocked. First

publication as yet unknown.

● Memory of Murder. The American Magazine, August 1946.

● Secret Corridors. The American Magazine July

1945. (Luke Bradley also appears.)

● Volcano. The American Magazine December 1945.

Both under his own name, Judson (Pentecost) Philips and as

his primary alter ego, Hugh Pentecost, this author of over 100 mystery

novels and collections, not to mention countless short stories for the

pulp and digest magazines, came up with as many series characters as

some writers do books. FOOTNOTE

Here is a list of the ones who appeared in

book form: Luke Bradley, Dr. John Smith, Lt. Pascal, Grant Simon,

Uncle George Crowder, Pierre Chambrun, John Jericho, Julian Quist, Jeff

Larigan, Alan Quist, Carol Trevor & Max Blythe, Coyle &

Donovan, and Peter Styles. This does not include his pulp fiction

characters, of which the members of the so-called Park Avenue Hunt Club

are perhaps the most well known and best remembered.

Dr. John Smith, who appears in this, Pentecost’s only

book in the Fingerprint series, is a psychiatrist by trade and a

detective by avocation, but as Mike Grost suggests on his website, “like a

lot of psychoanalytic fiction, it is grim and joyless stuff. A

character in ‘Volcano’ is a jovial artist with a huge red beard; he

seems like a dry run for the author’s later artist-sleuth, John

Jericho.”

Bill speaking here. I concur. He’s too

colorless (literally, according to how he’s described) for my

taste. Of all of the books that Philips-Pentecost wrote, there

are many others that would be a better choice as a first one to read.

Pentecost’s last mystery, Pattern for Terror, was published

by Carroll & Graf after his death at the age of 85 in 2002.

At his peak he wrote as many as three books a year. According to

his obituary in The New York Times,

he kept writing up until his death, dictating and using a magnifying

glass to compensate for failing eyesight.

FOOTNOTE.

Victor speaking. As to the origin of his pseudonym, Hugh Owen

Pentecost (sometimes the name is spelled Pentacost, incorrectly) was

Judson’s uncle, who died shortly after Judson was born. An

interesting sidenote is that Hugh Owen Pentecost had married Ida

Gatling, daughter of the inventor of the Gatling gun.

The Philip Owen pseudonym Philips used for one book (Mystery at a Country Inn, Berkshire

Traveller Press, 1979) is derived from his uncle’s middle name and

Judson’s own last name.

ALAN PRUITT

The Restless Corpse

1947

The author of only two

mysteries, of which The Restless

Corpse was the first, Alan Pruitt had a much more productive

career in the real world under his real name, Alvin Rose. As a

newspaperman in Chicago in the 1920s and 30s, he was one of the first

reporters on the scene of the 1929 St. Valentine’s Day massacre on

Clark Street. FOOTNOTE

Upon leaving the Navy in 1946 as a Lt. Commander,

Rose took over the job of commissioner of welfare for Chicago. He

served the city until 1967, when he retired as the executive director

of the Chicago housing authority. At the age of 64, he and

his wife then planned to move to the San Diego area where, according to

a newspaper article, he intended to write mystery novels and possibly

teach journalism.

He may have taught but no further books were

forthcoming. Rose died in 1983, the last fifteen years of his

life having been spent in California.

Not diverging far from his first career, both of his

two mysteries, the second one being Typed

for a Corpse, a Handi-Book paperback original which came out in

1951, featured Chicago Globe reporter Don Carson as their

protagonist. He is assisted in the sleuthing department by April

Holiday, the runaway daughter who is at the focal point of The Restless Corpse.

The blurb on the jacket of this latter book promises

“a new

high mark in breezy entertainment,” a case complicated by the body of

the walking dead man who just wouldn’t stay where he was put, an

ex-Capone mobster who quotes

Shakespeare, a white jade Buddha, and a telegram composed of chess

symbols. “It’s fast, funny, and furious, and the dialogue

sparkles as Don Carson and April Holiday set a new high in breezy

entertainment...”

Bill mildly disagrees, suggesting that this is

typical publisher hyperbole and that the book is not nearly as

wonderful as the description.

FOOTNOTE.

Born in Chicago in 1903, Rose almost assuredly came up with the his

pseudonym from his mother’s maiden name: Winona Pruitt.

|

|

VIRGINIA RATH

A Shroud for Rowena

|

1947

|

A Dirge for Her

|

1947

|

Virginia Rath was a native Californian who for much

of her life was active in San Francisco literary circles. Born

Virginia McVay in 1905, she taught high school in a mountain railroad

town, married a railroad telegrapher and worked in a railroad telegraph

office during World War II. FOOTNOTE (1)

Her career in writing detective fiction began much

earlier, however, beginning in 1935 with Death at Dayton’s Folly, one of the

Crime Club mysteries published by Doubleday. The book also marked

the first appearance of deputy sheriff Rocky Allan, who appeared in six

titles between 1935 and 1939, all with a California

setting. FOOTNOTE (2)

In Rocky Allan’s final appearance, Murder with a Theme Song, Virginia

Rath’s other series characters also played a role as a married couple

named

Michael and Valerie Dundas, who invariably used San Francisco as their

base of operations. They had arrived on the scene one year

earlier (1938) in the book The Dark

Cavalier.

As Rocky Allan faded out of the picture, the

Dundases appeared in Rath’s last eight books, including the two from

Ziff-Davis. The Dundases are amateur sleuths, but not in the Mr.

& Mrs. North vein. He’s a renowned San Francisco couturier

and does most of the detective work. Their cases are not cozys

exactly; they’re conventional whodunits in the Frances Crane/Leslie

Ford mode, usually involving S.F.’s upper crust, but the narration

includes scenes from the points of view of other characters, some of

whom are more earthy types, and there is plenty of wry humor.

Worth reading, says Bill, though he prefers her Rocky Allan stories.

A Dirge for Her

concerns a murdered movie actress, a missing six-year-old boy,

blackmail, family skeletons, and a $100,000 ransom demand. A Shroud for Rowena deals with a

suddenly vanished heiress, a private eye of dubious repute (again, not

“Nameless”), a couple of murders, burglary, and a putative ghost.

S.F. settings in both.

Although Shroud

was officially Virginia Rath’s last book, the lady was also one of the

authors behind the “Theo Durrant” group pseudonym, there being twelve

of them responsible in all, including Anthony Boucher, Eunice Mays

Boyd, Lenore Glen Offord and other members of the California branch of

the MWA. The book they wrote, The

Marble Forest, was published in 1951, but Rath did not live

until then, dying regrettably young at the age of 45 in October,

1950.

FOOTNOTE (1).

Virginia

Rath’s husband was Carl H. Rath. The town where they lived and

where

she taught school in was Beckwourth, CA. Looking at the census

records for 1930, almost everyone in town worked for the

railroad.

Beckwourth was named after a rather famous African-American, James

Pierson Beckwourth, an early California trader and

pioneer.

FOOTNOTE (2).

While in the process of jointly preparing these notes on the

Fingerprint authors, Steve came across an essentially unknown novel

written by Rath, one that appeared four years earlier than the first

mystery she did for Doubleday. Never published in book form, “The

Murders at Hillside” was the lead story in the July 1931 issue of Complete Detective Novel Magazine,

one of the few mystery pulps not completely indexed in the Cook-Miller

bibliography. At over 60,000 words in length, a rough count, it

is indeed a full-fledged novel. (Sometime pulp publishers

exaggerated a little.) None of Rath’s usual series characters

makes an appearance, so it not a tale that gained a new title when it

was published in hardcover. As a story not known to exist before,

its discovery came as quite a surprise.

PHYLLIS A. WHITNEY

Red Is for Murder

1943

Of the various authors

who wrote books for the Fingerprint line, Phyllis A. Whitney may not

have the honor of having written the most books in her career – that

honor goes to Judson Philips / Hugh Pentecost – but the time span

involved in her case is surely the longest. Red

Is for Murder was her first work of adult fiction, published

when she was 40 years old. The most recent of her approximately

forty novels is Amethyst Dreams

(Crown, 1997), which was published when she was 94. That book is

still in print, as are many of her earlier ones. FOOTNOTE

In 1988 the Mystery Writers of

America gave Ms. Whitney their Grand Master award for lifetime

achievement, the highest honor they can bestow. As for

the type of story on which her reputation is based,

she is an author whom the New York

Times once called the “Queen of the American Gothics.”

Last year at the age of 102, it is reported,

she was working on her

autobiography. (The link will take you to her home page.)

For several years after Red Is for Murder, Whitney

concentrated on children’s fiction. (Her first book, A Place for Ann (1941) was also in

the young adult category.) Her next adult mystery, The Mystery of the Gulls, did not

appear until well after the war was over, in 1949. The majority

of the titles for which she is best known were published in the 1960s

through the 1980s.

The jacket blurb for Red Is for Murder reads in part as

follows:

“How does it feel to be in a big [Chicago] department store after the

customers have hurried home and the lights have been darkened so that

eeriness reigns over the vast reaches of the floors? To Linell

Wynn, who writes sign copy for Cunninghams’, such a scene has always

seemed perfectly natural until the day that murder walks the floors at

dusk.

“The matter-of-factness of the police as they

question people whom she knows, works with every day, does nothing to

dispel the feeling that they are only temporarily holding back the

powers of darkness. Evil has struck once – and evil is hovering,

waiting to strike again [and soon] she stumbles upon death for the

second time.”

FOOTNOTES. Phyllis A. Whitney was born in Yokohama

of

missionary parents. Her middle name is “Ayame,” which is the

Japanese word for “iris.” Her mother’s first marriage was

to Gus Heege, who claimed to be the originator of the Swedish dialect

play, his most famous being “Yon Yonson.” After Whitney’s father

died in Japan, she and her mother returned to the US, where in 1920

(according to census records) she lived with her mother in the Devin

household, where her mother worked as a maid. In 1930 as Phyllis

Garner, she worked as a librarian in a circulating library in

Chicago. She must have married George Garner around 1925, as she

claimed to have been married for five years. For more information

on her long and productive life, follow the link above to her home

page.

THE ALLIANCE FINGERPRINT MYSTERIES

The Alliance Book Corporation was established in New

York City in 1938, and according to short notes in the New York Times (July 9 and Oct 24

1938), its original intention was to handle “the works of German and

Austrian authors living outside Germany and Austria, and [to] publish

these works in the German language,” as well as in English.

Their first list, Fall and Winter 1938-39, included works

by Vicky Baum, Thomas Mann, Emil Ludwig, and others.

President of the company at its founding was Henry G.

Koppell (1895-1964; born Heinz Guenther Koppell) who had founded the

German Book Club in Germany in 1924.

In May, 1942, it was announced that Ziff-Davis had purchased the

Alliance Book Corporation, with Koppell continuing as president, but he

left the company later that year ( New

York Times, 11 Dec 1942). Initially the Alliance imprint

was meant to have been kept as a separate entity, but according to the Times (11 Jan 1943) all three names

were to appear on the books of the firm.

Before its takeover by Ziff-Davis, Alliance had

published four books in its “Fingerprint Mystery” line. The

announcement of this new publishing program was made in the New York Times (22 June 1941), with

one of the first of these books being I

Am Saxon Ashe, by an anonymous author.

The first Fingerprint Mysteries published by the

Alliance Book Corporation:

|

Author

|

Title

|

Date of Publication

|

Review Date

(New York Times) |

1941

|

Saxon Ashe

|

I Am Saxon Ashe

|

August 29, 1941

|

September 7, 1941

|

|

James

Warren

|

No Sleep at All |

September

25, 1941

|

September 28, 1941

|

1942

|

Saxon Ashe

|

Saxon Ashe – Secret Agent

|

March 3, 1942

|

April 19, 1942

|

|

Gelett Burgess

|

Ladies in Boxes

|

April 24, 1942

(Previously published

in the Toronto Star Weekly,

May 17, 1941.)

|

May 3, 1942 |

A mystery entitled Murder

with Music, by Gilbert Riddell, is listed in Hubin’s Crime Fiction IV as being

published by Alliance in 1935, but this was a company called Alliance

Press and a

totally different entity.

The two Saxon Ashes are spy/adventure novels

featuring “the exploits of Bibobi the agile mimic, boxer, acrobat [the

public persona of Saxon Ashe], and of his twin brother Sir Hubert

Darendyck – both employed as secret agents by the English Intelligence

Service.” Saxon Ashe – Secret

Agent takes place in Amsterdam and

other parts of Holland and behind enemy lines in Germany, and concerns

the thwarting of Nazi efforts to infiltrate and invade Holland. A

copy of I Am Saxon Ashe is

not at hand, but

a blurb on the back jacket of the Warren novel says of it, “Take a dash

of the Scarlet Pimpernel, a bit of

Bulldog Drummond, a touch of Buchan, shake well and add the special

qualities of this anonymous author’s skill and imagination, bring to a

boil in the Second World War, and you may have a faint idea of the

thrills and excitement that await you.”

Copyright records for the second Saxon Ashe book

have revealed that the previously unknown author was Victor

McClure [sic]. More than likely, this was meant to be Victor

MacClure, 1887-1963, who had a dozen mystery thrillers published under

his own name between 1923 and 1937. In his

review of the book in the New York

Times Book

Review, Isaac Anderson didn’t think too

highly of

it, commenting that “despite the violent and

perilous exploits with

which it deals, the book makes dull reading.”

Perhaps Mr. MacClure

should have remained anonymous.

As you will see from the front cover of

the second Ashe novel, the Fingerprint logo is prominently displayed on

the front cover.

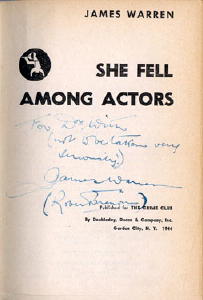

No Sleep at All,

by James Warren, was also published first in England. It is a

moderately hardboiled, Peter Cheyney-type mystery narrated by a

protagonist also named James Warren, a young Scotland Yard detective

constable who investigates murder and devious doings among London’s

pre-war night club set. Fast-paced and well-written, says Bill,

with credible characters and clipped dialogue.

This was Warren’s first mystery in a career that

lasted from 1941 to 1958, eight books in all, but only the one from

Alliance. A gent by the name of James Weston appeared in several

of the later books, all somewhat tamer than the first, one of them

being She Fell Among Actors,

which was

published by Doubleday’s Crime Club in 1946. (According to Al

Hubin, “James Warren” was almost certainly a pseudonym, and which books

Weston was in, as opposed to Warren, is currently being

investigated.) FOOTNOTE (1)

The greatest mystery behind Gelett Burgess’s Ladies in Boxes may be why there

are no copies available for sale anywhere at the moment online.

Bill confesses that not even he has a copy. Burgess, of course,

was (and is) far better known as a humorist and a poet – you probably know the one about

the purple cow. He also wrote a few works of crime and mystery

fiction, listed in Hubin. The most well-known of these

may be Find the Woman

(Bobbs-Merrill, 1911) . FOOTNOTE (2)

From a review in the New York Times (May 3, 1942),

we learn that the boxes are coffins, not suprisingly,

and they are filled with three exquisitely beautiful women whom a gypsy

palmist predicted would die within a week. All three die the very

next day, and the question is, who killed them? There are any

number of suspects, all members of a high society set. “The man

who eventually solves the problem is Bob Catfield, a police detective

familiarly known as ‘Bobcat.’ It is quite easy to believe that

all of the characters in this story are imaginary. Not one of

them suggests anything more lifelike than a puppet.”

Ouch. This was the last of Burgess’s seven

entries in Hubin, and the last Fingerprint Mystery from Alliance before

Ziff-Davis took over. It was the only one of the four from

Alliance to have been published in the US first, and in fact it had no

British publication.

FOOTNOTE

(1). As we continue to discover more information,

it will

be included in these notes as we go. Here is the first of two

such examples, this one courtesy of Al Hubin. Prompted to look

further into the matter of pseudonymous James Warren, he found two

items offered separately on ABE but each connecting Warren somehow with

the

name Robert Brendon. The implication was that Warren was a

pseudonym of Robert Brendon, but without knowing, of course, it could

easily be the other

way around. Al emailed both booksellers, and replies came

back quickly.

Doug Sulipa of Comic World in Manitoba,

Canada, responded first, saying that he had run across a story or an

article by Brendon in an obscure magazine, perhaps a men’s adventure

type, that suggested that Brendon was actually James Warren. He

had kept a note on the reference but no longer had the magazine.

Even with Doug’s input to go by, this did not get

around the fact that the leading character and the stated author are

one and the same in No Sleep at All.

This is what made it still seem more likely that the James Warren

byline was the pseudonym and not the reverse.

Then came an email reply from Paula Chihaoua of Addyman Books in Hay-on-Wye

in the UK, and this was the clincher. Their copy of She Fell Among Actors was inscribed

by the author on the title page, as you will see in the image to the

right. He signed it first as James Warren and underneath,

in parentheses, as Robert Brendon, his real name. One more piece

of data verified.

FOOTNOTE (2). One

of Burgess’s earlier works of crime fiction, The Master of Mysteries, was

published anonymously by Bobbs-Merrill in 1912. Subtitled

“Being an Account of the Problems Solved By Astro, Seer of Secrets, and

His Love Affair With Valeska Wynne, His Assistant,” the book is a

collection of short stories, all cases solved by one Astrogen Kerby, or

‘Astro’ for short.

Quoting a

website dedicated to The Classical English

Detective Novel, as one source, we learn more:

In America, in 1912,

the occult detective – crystal and all – [in the form of] Astrogen Kerby, who appeared in The Master of Mystery

by Gelett Burgess, was introduced. The book was very cryptic and

mysterious in the sense that it was published anonymously.

However, if

you take the first letter in each of the 24 short stories you get the

following message: “The

Author is Gelett Burgess,”

and if you take the

last letters you get: “False

to Life and False to Art.”

This kind of thing is not unique. If you get the chance, try to

read the first letter of each chapter of The Greek Coffin Mystery by Ellery Queen and

see what kind of message it yields.

The Master of Mysteries is a Queen’s

Quorum selection, and while it is scarce, three copies are

available at the moment on ABE. (The asking prices are in the

$150-$200 range.) What Victor has discovered about Ladies in Boxes, however, from a

small news item in the New York Times

for April 9, 1942, is that advance copies were called back from book

reviewers before publication. “It seems that Mr. Burgess, as is

his way, had worked in an acrostic and that printing difficulties had

garbled the cryptogrammic message. Reprinting done, the book is

announced for April 24.”

All we can do is wonder

what the acrostic was in this case. (A copy is on order from

Inter-Library Loan, so we may soon know.)

Copyright

© 2006, 2009 (slightly revised version) by

Bill Pronzini, Victor

A. Berch and Steve Lewis

THE ZIFF-DAVIS FINGERPRINT

MYSTERIES

A Chronological

Listing, by Victor Berch

|

Author

|

Title

|

Publication

Date (*)

|

Review

Date (**)

|

|

|

|

|

|

1943

|

Amelia Reynolds Long

|

The Triple Cross Murder

|

Oct 26, 1943 *

|

Oct 31, 1943

|

|

Phyllis A. Whitney

|

Red Is for Murder

|

Oct 26, 1943

|

Oct 31, 1943

|

|

|

|

|

|

1944

|

Amelia Reynolds Long

|

Symphony in Murder

|

June 3, 1944

|

June 8, 1944

|

|

|

|

|

|

1945

|

Amelia Reynolds Long

|

Death Looks Down

(***)

|

March 15, 1945 *

|

April 1, 1945

|

|

|

|

|

|

1946

|

Milton K. Ozaki

|

The Cuckoo Clock

|

July 5, 1946

|

Aug 4, 1946 (CT)

|

|

Brett Halliday

|

Blood on Biscayne Bay

|

Oct 31, 1946

|

Nov 24, 1946

|

|

Bruno Fischer

|

The Pigskin Bag

|

Dec 6, 1946

|

Dec 22, 1946

|

|

|

|

|

|

1947

|

Brett Halliday

|

Counterfeit Wife

|

May 13, 1947

|

May 25, 1947

|

|

Virginia Rath

|

A Shroud for Rowena

|

May 27, 1947

|

June 1, 1947

|

|

Bill Goode

|

The Senator’s Nude

|

May 29, 1947

|

June 8, 1947

|

|

Alan Pruitt

|

The Restless Corpse

|

May 29, 1947

|

June 22, 1947

|

|

D. B. Olsen

|

Widows Ought to Weep

|

June 4, 1947

|

June 22, 1947

|

|

Milton K. Ozaki

|

A Fiend in Need

|

June 6, 1947

|

June 29, 1947

|

|

Bruno Fischer

|

More Deaths Than One

|

July 15, 1947

|

July 27, 1947

|

|

Leonard Gribble

|

Atomic Murder

|

Sept 23, 1947

|

Oct 5, 1947

|

|

Leonard Lee

|

The Twisted Mirror

|

Oct 1, 1947

|

Nov 3, 1947

|

|

Richard Burke

|

The Red Gate

|

Oct 21, 1947

|

Dec 7, 1947

|

|

R. L. Goldman

|

The Purple Shells

|

Oct 21, 1947

|

Nov 16, 1947

|

|

Hugh Pentecost

|

Memory of Murder

|

Oct 28, 1947

|

Nov 16, 1947

|

|

Virginia Rath

|

A Dirge for Her

|

Oct 28, 1947

|

Oct 31, 1947 (CS)

|

|

|

|

|

|

1948

|

Helen Farrar

|

Murder Goes to School

|

Jan 13, 1948

|

Jan 18, 1948

|

|

Brett Halliday

|

Michael Shayne’s Triple

Mystery

|

March 4, 1948 *

|

May 9, 1948

|

|

Richard Burke

|

Sinister Street

|

March 16, 1948 * |

April 28, 1948 (SRL)

|

|

D. B. Olsen

|

Cats Have Tall Shadows

|

March 29, 1948

|

April 11, 1948 (SFC)

|

|

Bruno Fischer

|

The Bleeding Scissors

|

April 23, 1948

|

May 2, 1948

|

|

|

|

|

|

NOTES:

* = Copyright registration date. ** = All reviews from the NY Times except where noted.

CT = Chicago Tribune; CS = Chicago Sun; SFC = San Francisco Chronicle; SRL = Saturday Review of Literature.

*** = The copyright date is 1944, which

could be a typographical error or the date of a serialization of some

sort. Or, even a story or condensed version under a different

title. Or, even still, it was intended for publication in 1944

and production was delayed.

Copyright © 2006 by

Victor

A. Berch.

YOUR COMMENTS ARE WELCOME.

|