Robert Allison “Bob” Wade

(1920-present) and H. Bill Miller (1920-61) penned their novels using

the joint pseudonym of Wade Miller. Their writing tandem followed

the highly successful Ellery Queen team of Frederic Dannay and Manfred

B. Lee, who produced top-notch mystery fiction from 1929 to 1958. Robert Allison “Bob” Wade

(1920-present) and H. Bill Miller (1920-61) penned their novels using

the joint pseudonym of Wade Miller. Their writing tandem followed

the highly successful Ellery Queen team of Frederic Dannay and Manfred

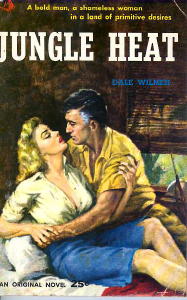

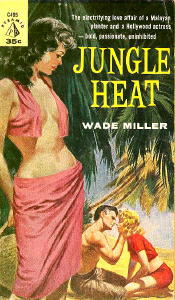

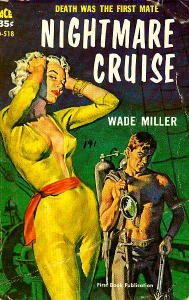

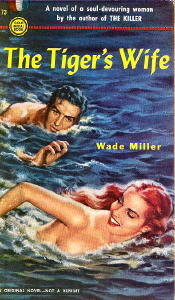

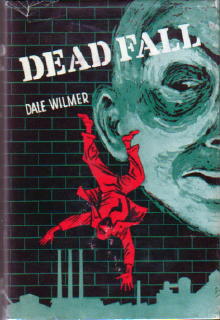

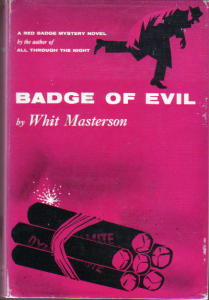

B. Lee, who produced top-notch mystery fiction from 1929 to 1958.Other bylines for Wade Miller such as Will Daemer, Dale Wilmer, and Whit Masterson were also pressed into service. Between the years 1946 to Mr. Miller’s premature death on August 21, 1961 from a sudden heart attack, they produced some thirty-three books. Counting two made-for-TV movies, nine titles were filmed in all. This includes Orson Welles’ noir classic TOUCH OF EVIL, which was adapted from their novel, Badge of Evil. The two future authors first met while 12-year-olds taking violin lessons. Friends for life, they attended San Diego State and together edited the campus newspaper and literary magazine. After leaving in their senior year in 1942, they enlisted in the Air Force and after the war resumed their joint ventures. Fawcett Gold Medal published the brunt of their creative output. In addition, they wrote novelettes, short stories, and television plays, including for Alfred Hitchcock Presents. The back cover copy to Evil Come, Evil Go which included a photograph of the team also lent some insights about their collaborations: The first question asked them is always:

‘How do you work together?’ Their usual answer is: ‘Wade writes

the nouns and Miller the verbs.’ Actually, their method is

similar to building a house, each man contributing his particular

talents and skills. After discussing an idea at length, they

outline extensively. Then Wade rushes through a first draft,

Miller rewriting close behind, and they revise the result aloud, which

amounts to a third draft. But the real secret to the success of

this method is that, after thirty years, Wade and Miller think so much

alike they have never had a major argument regarding their work.

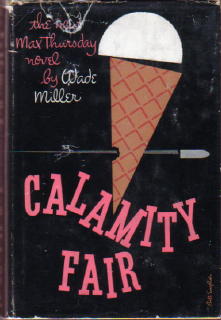

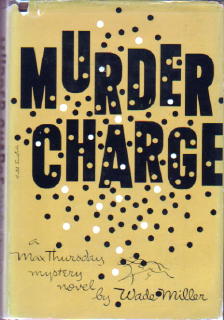

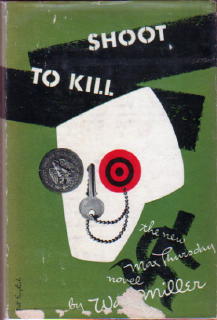

Among the Wade Miller early entries was the PI Max Thursday series generally held as one of the best from the post-war era. Something of an alcoholic and loner, the PI Max Thursday character was also flawed and complex enough to escape the private detective cliché. Thursday’s life and career, moreover, evolved in interesting twists and turns throughout the series. Mr. Wade mentioned in a March 1984 interview that he had worked on a manuscript to revive PI Max Thursday, but it has never been published. After 1961, Mr. Wade went on alone to publish hardcover noir and such police procedurals as 711–Officer Needs Help and Play Like You’re Dead under the Whit Masterson pen-name with Dodd, Mead. By the close of the 1970s, he had abandoned his solo efforts. His last published novel was The Slow Gallows in 1979. All totaled, Mr. Wade had a hand in writing forty-six novels, a prodigious yet high quality output. In the ensuing years, Mr. Wade wrote for television and the cinema. His clients included Walt Disney and the San Diego Zoo. The Private Eye Writers of America’s 1988 Lifetime Achievement Award recognized Mr. Wade for his contributions to the genre. The award presentation was made at the San Diego Boucheron conference. A generation earlier in 1956, the Wade Miller tandem had been awarded the Mystery Writers of America Edgar Allan Poe Award. The Wade Miller team was also nominated for Best Short Story in 1956 (“Invitation to an Accident” in the July 1955 EQMM). More recently, Mr. Wade was given the 1998 City of San Diego Local Author Achievement Award. Still an active octogenarian, he writes a monthly mystery wrap-up column called “Spadework” for the San Diego Union Tribune. From this vantage point, he can survey past and present crime writing. He has praised such crime authors diverse as Martha Lawrence, Robert Crais, Rochelle Krich, Sue Grafton, Donald Westlake, Marianne Wesson, and Janet Evanovich. While researching “Wade Miller” on a google search, most of the hits refer to the Houston Astro’s right-hand pitching ace with the same name. For some perspective, this Wade Miller was born in 1976 about the same time Mr. Wade was winding down his novelist career. Indeed, the author tandem Wade Miller has all but passed from the current literary scene. That is a shame, too. As Bill Crider posed in his Gold Medal column from Mystery*File #40, today’s crime authors don’t write books like they use to in the 1950s. Wade Miller has attracted some recent notice. In 1993 HarperPerennial reissued four PI Max Thursday titles: Calamity Fair, Murder Charge, Shoot to Kill, and Uneasy Street. Their works have been translated into as many as sixteen foreign languages including Swedish, Japanese, French, German, Italian, and Finnish. Modern practitioners in the crime writing genre such as Bill Crider and James Reasoner find much to admire about the Wade Miller oeuvre.  For me, it’s always a

style thing. The Wade Miller titles typified the top-notch Gold

Medal books. Their novels, clocking in at around 160 pages, show

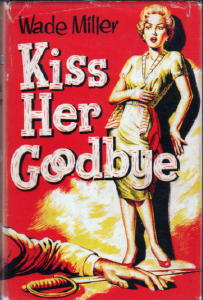

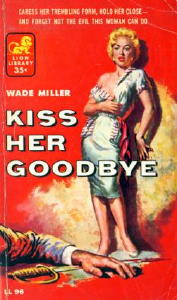

lean prose, tight plots, and controlled voice. Kiss Her Goodbye was a stand-alone

title issued not by Gold Medal, but Lion Library out of New York

City. Lion House was a paperback house also publishing the likes

of noir-meister Jim Thompson and Mississippi novelist Ben Ames Williams. For me, it’s always a

style thing. The Wade Miller titles typified the top-notch Gold

Medal books. Their novels, clocking in at around 160 pages, show

lean prose, tight plots, and controlled voice. Kiss Her Goodbye was a stand-alone

title issued not by Gold Medal, but Lion Library out of New York

City. Lion House was a paperback house also publishing the likes

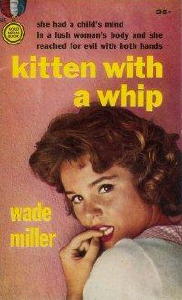

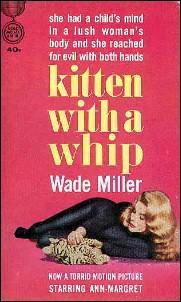

of noir-meister Jim Thompson and Mississippi novelist Ben Ames Williams.Kiss Her Goodbye appeared in 1956, three years before the authors’ most colorfully titled novel, Kitten with a Whip. This novel became a movie in 1964, a drive-in theater fare starring Ann-Margret and John Forsythe. Wade Miller later wrote the screenplay for KISS HER GOODBYE, a homonymous movie slated to star Charlton Heston, Robert Taylor (the antagonist), and Barbara Lang, a Marilyn Monroe lookalike starlet. When that deal fell through, it was made into a largely forgettable film in 1959 starring Andrew Prine, Steven Hill (the DA in the original Law and Order TV series), and Sharon Farrell. The movie, however, treats the female lead as only a precocious, adult-looking girl. The novel, however, concerns a young, beautiful, but also mentally challenged young lady named Emily Darnell. This premise leaves open many possibilities for cheap exploitation: men having their way with a full-figured desirable woman having the mind of a twelve-year-old. The lusty blurb topping the front cover almost suggests this: “Caress her trembling form, hold her close – and forget not the evil this woman can do.” The lurid cover art illustrates a curvaceous blonde with the reddest pouty lips, her flimsy white sundress ripped from one shoulder down to the upper hemisphere of her breasts. Intrigued, I recently plunked down the three dollars for a paperback that in 1956 cost 35 cents. Thankfully, the book is a far, far cry from how the still bright crimson wrapper portrays it. The opening sentences, terse and spare and vivid, are the narrative hook:  Where the earth is unmasked it is called

desert. It is the naked face of the earth and it is strangely

expressionless. Where the earth is unmasked it is called

desert. It is the naked face of the earth and it is strangely

expressionless.The two people in the car had driven all day through the searing heat. The man’s name was Ed Darnell, the girl’s name was Emily. It was nearly sundown but the heat was still fierce and the sky still vast and bright. Under a sky that size, not even the earth seemed very important. Reading about this desert landscape echoes the prose style of W.R. Burnett, Bill Pronzini, and to nail down the point, Tony Hillerman. We are sucked into the setting from the sheer force of its description, beginning with the first two lines’ stark imagery. Ed Darnell and his sister Emily have fled Bakersfield, California for a new chance with hopefully better odds in Barstow. They make it as far as Jimmock and beset by an automobile breakdown are forced to rent a cabin from an older man named Tubbs. Tubbs looks out his office window at Emily: Emily stood before a jasmine bush, her

lithe figure outlined in the glow of the headlights. The white

radiance pierced the gossamer of her frock here and there, intimating

the turn of her thigh, the upsweep of her breasts.

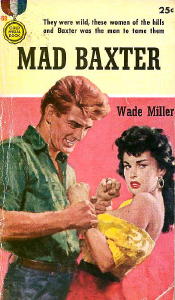

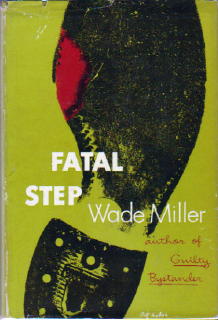

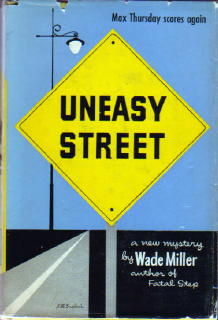

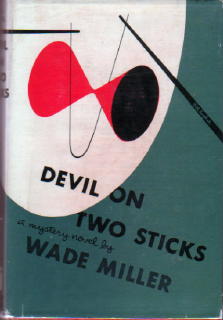

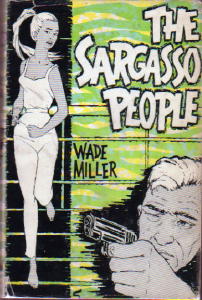

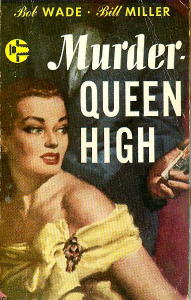

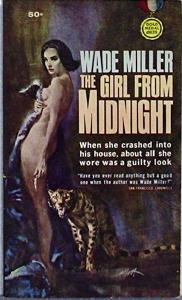

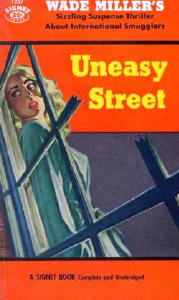

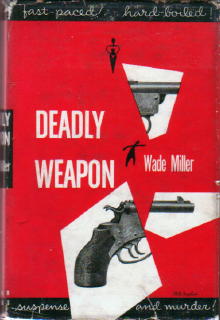

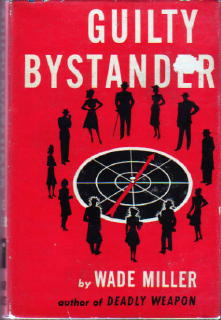

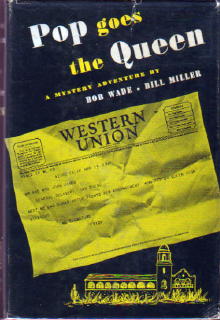

Of course, therein lies the rub. Nobody believes Ed’s glib explanation that Emily is his half-witted sister and must be protected. While Ed hunts for gainful employment, Emily lounges around the cabin, unsuspectingly attracting all sorts of men trouble. Among her ardent admirers is a married alcoholic lout named Cory Sheridan. Ed, meantime, fixes his romantic interests on a local business lady, Marge. Cory Sheridan, through a sly contrivance transparent to all except Emily, lures her to his mansion when his wife is out of town. The seduction scene is brief. Later, Cory is discovered murdered and suspicion falls on the hapless Emily. Again, Ed is forced to go to incredible lengths to rescue her. Without giving away the novel’s ending, all this conflict plays out in a sensitive while unsentimental manner. Ed remains a sympathetic protagonist. All the hallmarks making for effective hardboiled writing are present here. Dialogue is laconic; action verbs are visceral; monologues are streamlined. The writing style is unadorned and plain but the prose is not parched and parsed to the point of becoming soulless or tedious. I don’t grow tired of reading it. By contrast, most paper blockbusters in every supermarket throughout America bore me to tears. One aspect I find appealing about a Gold Medal book is the assemblage of 1950s lore and pop culture. You can almost see and smell and hear the insides of old movie theaters, cars, and rented cabins. Take rented cabins, for instance. Today I drive by the cinderblock ruins to such a refuge. I wonder, Who lodged there? Now I know. Ordinary but desperate folks like Ed and Emily Darnell. With highway expansion slated in a few years, these ruins will be bulldozed into oblivion. Another Gold Medal book rich in its 1950s details is John D. MacDonald’s Dead Low Tide (1953). Both books evoke nostalgia but the kinetic plot of each tale leave little time for savoring it. Wade Miller wrote and published about the same time as such hard-boiled writers as Mickey Spillane. The Wade Miller novels, however, are stronger on story line and characterization. Perhaps their one-two punch approach to the writing process resulted in creating novels more accomplished in these aspects. Wade Miller titles:  Deadly Weapon. Farrar, hc, 1946. Guilty Bystander. Farrar, hc, 1947. [PI Max Thursday.] Pop Goes the Queen. Farrar, hc, 1947. aka Murder–Queen High, Graphic, pb, 1949. Fatal Step. Farrar, hc, 1948. [PI Max Thursday.] Uneasy Street. Farrar, hc, 1948. [PI Max Thursday.] Devil on Two Sticks. Farrar, hc, 1949. aka Killer’s Choice, Signet, pb, 1950. Calamity Fair. Farrar, hc, 1950. [PI Max Thursday.] Murder Charge. Farrar, hc, 1950. [PI Max Thursday.] Devil May Care. Gold Medal, pbo, 1950. Stolen Woman. Gold Medal, pbo, 1950.  The Killer. Gold Medal, pbo, 1951. The Tiger’s Wife. Gold Medal, pbo, 1951. Shoot to Kill. Farrar, hc, 1951. [PI Max Thursday.] Branded Woman. Gold Medal, pbo, 1953. The Big Guy. Gold Medal, pbo, 1953. South of the Sun. Gold Medal, pbo, 1953. Mad Baxter. Gold Medal, pbo, 1955. Kiss Her Goodbye. Lion, pbo, 1956. Kitten With a Whip. Gold Medal, pbo, 1959. Sinner Takes All. Gold Medal, pbo, 1960. Nightmare Cruise. Ace, pbo, 1961. aka The Sargasso People (British hc)  The Girl From Midnight. Gold

Medal, pbo, 1962. The Girl From Midnight. Gold

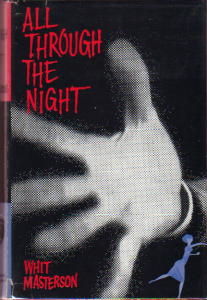

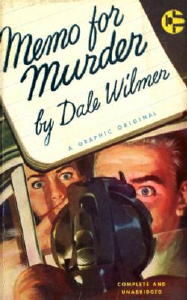

Medal, pbo, 1962.Will Daemer title: The Case of the Lonely Lovers. Farrell, digest pbo, 1951. Dale Wilmer titles: Memo for Murder. Graphic, pbo, 1951. Dead Fall. Mystery House, hc, 1954. Jungle Heat. Pyramid, pbo, 1954. -Reprinted as by Wade Miller. Whit Masterson titles: All Through the Night. Dodd Mead, hc, 1955. aka A Cry in the Night, Bantam, pb, 1956. Dead, She Was Beautiful. Dodd Mead, hc, 1955.  Badge of Evil. Dodd Mead, hc, 1956. aka A Touch of Evil, Bantam, pb, 1958. A Shadow in the Wild. Dodd Mead, hc, 1957. The Dark Fantastic. Dodd Mead, hc, 1959. A Hammer in His Hand. Dodd Mead, hc, 1960. Evil Come, Evil Go. Dodd Mead, hc, 1961. NOTE: Evil Come, Evil Go was the last collaborative effort of the two authors, and The Man on the Nylon String was the beginning of Robert Wade’s solo efforts. The Man on a Nylon String. Dodd Mead, hc, 1963. 711–Officer Needs Help. Dodd Mead, hc, 1965. aka Warning Shot, Popular Library, pb, 1967. Play Like You’re Dead. Dodd, Mead, hc, 1967. The Last One Kills. Dodd Mead, hc, 1969.  The Death of Me Yet.

Dodd Mead, hc, 1970. The Death of Me Yet.

Dodd Mead, hc, 1970.The Gravy Train. Dodd Mead, hc, 1971. aka The Great Train Robbery, Pinnacle, pb, 1976. Why She Cries, I Do Not Know. Dodd Mead, hc, 1972. The Undertaker Wind. Dodd Mead, hc, 1973. The Man with Two Clocks. Dodd Mead, hc, 1974. Hunter of the Blood. Dodd Mead, hc, 1977. The Slow Gallows. Dodd Mead, hc, 1979. Robert Wade titles: The Stroke of Seven. Morrow, hc, 1965. Knave of Eagles. Random House, hc 1969. Movie Adaptations:  Guilty Bystander (1950) adapted from Guilty Bystander. Starring Zachary Scott and Faye Emerson. A Cry in the Night (1956) adapted from All Through the Night. Starring Edmond O’Brien and Natalie Wood. Touch of Evil (1958) adapted from Badge of Evil. Starring Charlton Heston and Janet Leigh. Kiss Her Goodbye (1959) adapted from Kiss Her Goodbye. Starring Andrew Prine, Steven Hill, and Sharon Farrell. The Yellow Canary (1963) adapted from Evil Come, Evil Go. Starring Pat Boone and Barbara Eden. Script by Rod Serling. Kitten with a Whip (1964) from Kitten with a Whip. Starring Ann-Margret and John Forsythe. Screenwriter & director: Douglas Heyes. Warning Shot (1967) adapted from 711–Officer Needs Help. Starring David Jansen and Ed Beagley. Television Screenplays: [This section is almost assuredly incomplete.] South of the Sun. March 3, 1955. CBS Climax series. Starring Jeffrey Hunter and Margaret O’Brien. The Woman in His Life. 1958. NBC The Investigator series. Starring Jeff Pryor and Lloyd Pryor. Invitation to an Accident. 1959. CBS Alfred Hitchcock Presents series. Starring Gary Merrill. The Manhunter. Adapted from the novel The Killer. 1968. Ron Roth Productions at Universal TV. Directed by Don Taylor. Starring Sandra Dee and Roy Thinnes. The Death of Me Yet. Adapted from the Whit Masterson novel of the same name. 1971. Aaron Spelling Productions. Directed by John Llewellyn Moxey. Starring Doug McClure and Darren McGavin.

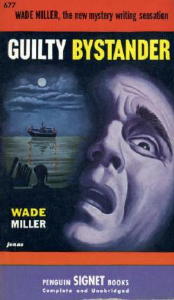

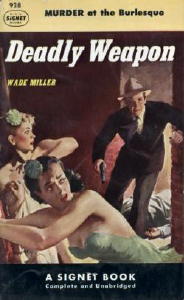

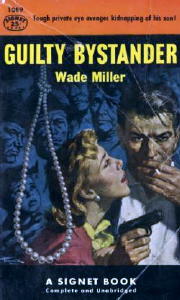

It seems that by the application of a literary Gresham’s Law, bad private detectives drive out good ones. How else can one explain the short career of Max Thursday who left the scene after only six novels, published 1947 to 1951, while Mike Hammer, with his appeal to the horny teenager in many of us, went on so much longer. Thursday was the creation of Wade Miller, a joint pseudonym of Robert Wade (1920- ) and Bill Miller (1920-1961). The first Wade Miller novel, Deadly Weapon (1946) is a precursor to the Max Thursday series. Though Thursday never appears, a leading protagonist is his good friend, Austin Clapp, head of San Diego’s Homicide Squad, investigating a series of murders beginning with one in a local burlesque theatre. Anthony Boucher called it a “highly satisfactory debut” and praised its ending; Edward D. Hoch has called that ending “unique.”  Clapp appears in all the

Max Thursday novels. As the

first of these, Guilty Bystander

(1947), begins, Thursday is sleeping off an alcoholic binge in a seedy

Skid Row hotel where, by the charity of the owner, he is house

detective. He is awakened by his ex-wife Georgia; their

five-year-old son has been kidnapped. It is with this compelling

opening that the short career of Max Thursday begins. Guilty Bystander was filmed in

1950, with Zachary Scott as Thursday. Clapp appears in all the

Max Thursday novels. As the

first of these, Guilty Bystander

(1947), begins, Thursday is sleeping off an alcoholic binge in a seedy

Skid Row hotel where, by the charity of the owner, he is house

detective. He is awakened by his ex-wife Georgia; their

five-year-old son has been kidnapped. It is with this compelling

opening that the short career of Max Thursday begins. Guilty Bystander was filmed in

1950, with Zachary Scott as Thursday.Thursday had been an operative for the Consolidated Detective Agency before leaving to serve in the Marines. He returns to civilian life, after serving in the bloody invasion of Saipan, with “bum nerves.” When his marriage breaks up, partly because he refuses to go into another profession, Thursday begins to drink. He eventually turns his life and career around. However, throughout the series he displays a hair-trigger temper, so much so that he is reluctant to carry a gun, fearing he will use it in anger. Thursday is in his mid-thirties, a tall, thin man with very black hair and “a face that escaped sheer ugliness by the highness of his cheekbones and the strong arch of his nose.” His gaunt appearance seems at first due to his drinking but then later due to hard work and little sleep. He is a man of literary tastes. On two occasions when Miller allows him to relax, he is reading novels by Conrad and Cabell. One of the breed of honest Southern California private detectives, Thursday is self-deprecating regarding this, saying, “Anybody that makes loud noises about ethics like I do isn’t any paragon, you can bet.” Still, we never see any evidence to doubt his honesty, and he was perhaps best characterized by the client who described him as “a sort of cavalier manqué.” His friends are few except for Clapp, the hard-bitten, veteran detective whose personal philosophy is an important part of each book. Clapp sees the human propensity for violence. His observation “Man is the only deadly weapon” was used in the title of Miller’s first book. Thursday’s girl friend in the series is Merle Osborn, crime reporter for the San Diego Sentinel. Their relationship is never smooth, but always interesting. Written in far less permissive times than the present, the series is evidence that those times brought out the best in both writer and reader. The writer had to use greater skill, and the reader greater imagination. Sex is handled with considerable subtlety, and the result is actually more erotic than the novels written since the “swinging sixties.” Even cursing is kept to a minimum so that, when employed, the words emphasize frustration and anger.  San Diego is

portrayed with the obvious knowledge of

the authors. They are especially good at conveying the influence

of the U.S. Navy base on the city and its economy and the nearness of

Tijuana, Mexico. San Diego is

portrayed with the obvious knowledge of

the authors. They are especially good at conveying the influence

of the U.S. Navy base on the city and its economy and the nearness of

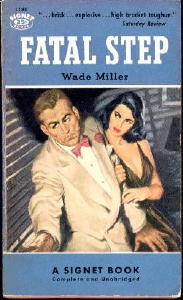

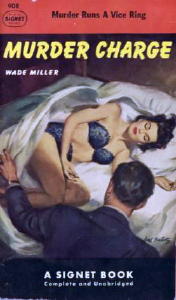

Tijuana, Mexico. The plots of the Thursday novels are not wildly original, but they generally have some element that makes them unusual. In Uneasy Street (1948) Thursday is hired to deliver an antique music box which proves to contain $100,000. Fatal Step (1948) has a well-realized carnival setting, and in Murder Charge (1950), arguably the best book in the series, Thursday has to infiltrate a criminal syndicate. The Thursday books were all published in hardcover by Farrar, Straus. After that series ended, Miller began publishing paperback originals, mainly for Gold Medal, and in 1955 they began an association with Dodd Mead, publishing in hardcover under the pseudonym “Whit Masterson.” Their few short stories are also noteworthy. “Invitation to an Accident” (1955) and “A Bad Time of Day” (1956) won Second Prizes in EQMM’s then-annual contest. A later story, the “The Memorial Hour” (1960), is even better but was published in year when the contest was not held. In 1952 Dorothy B. Hughes, one of our best critics and novelists, said of Wade Miller, “No one writes the hard-boiled mystery better.” Yes, there was Hammett and Chandler, but she wasn’t far off the mark. NOTE: This is a

considerable revision of an article that first appeared in The Armchair Detective, Vol 8, No

3, 1975.

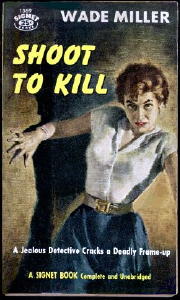

Very little is known about Max Thursday’s early life except that he attended State College. Prior to WWII, he worked as a P. I. for an agency called Consolidated. He then joined the Marines and served in WWII. After the war he could not find work and Max started drinking. His alcoholism led to the breakup of marriage. When we first meet him, he has been divorced from his wife Georgia for four years. They have a son named Tommy who is 5 ½ years old. Max is 6’ tall, has blue eyes, black hair and is a smoker. Max is the Bridgway Hotel chief detective working for the free room and board. The hotel is located between Island and J on 5th Avenue in San Diego. Max’s police contact is Lt. Austin Clapp of the San Diego Homicide Department (a character who also appears in the one book about P. I. Walter James by Wade Miller). GUILTY BYSTANDER (Farrar, 1947) takes place in February and Max has let his P. I. license expire. The story begins when Max gets a visit from Georgia whose current husband Dr. Homer Mace has left town and disappeared. Worse, she has received a ransom note for Max’s son Tommy. Max’s first step on the case is to interview Mace’s partner, Dr. Randolph Elder. When Elder is murdered the cops figure either Max or Georgia are the perpetrators, and believe that is strengthened when Homer’s dead body is also found. A single pearl left in Elder’s desk leads Max and cop pal Lt. Austin Clapp on the trail of some hot jewels that seem to inspire the worse in any person who gets anywhere near them. This leaves a trail of corpses across the San Diego landscape, and the action leads back to the hotel and a confrontation with a killer. Very hard-boiled, very well written and this near classic is highly recommended.  FATAL STEP (Farrar, 1948) takes place in August, six months after Guilty Bystander. Max has a new fourth floor office in the Moulton Building with “Private Investigator” on the glass door. He has moved his living quarters to one half of a white stucco duplex at Union and Ivy in the Middleton section of San Diego. He has renewed his P. I. license and purchased a gray Oldsmobile sedan. He is reading Cabell’s Figures of Earth. On this case, he meets Merle Osborn, a reporter for the San Diego Sentinel, and they become friends. In Fatal Step, Max is on the scene at Joyland when a young Chinese boy is slain. The boy’s father asks Max to clear his son’s name from the accusations that arise after the murder. Working his investigation hand in hand with Lt. Clapp, Max has to form an unwanted alliance with Merle Osborne in order to penetrate the gambling empire of Larons and Ulaine Tarrant. The illegal gambling houses seem to be the focus of the murder, a gang war, and some arson. Max is a strong character, here left brooding over the consequences of the use of his gun in Guilty Bystander, making him a tough character with a sensitive inner soul. A well-organized plot coupled with well-drawn supporting characters, both major and minor, adds real insight in the human condition and makes this another highly recommended title in the series. UNEASY STREET (Farrar, 1948) takes place in December. Max has sold his guns and turned in his P. I. license as he is troubled by the deaths he has caused. Handed a music box by a dying woman, Max finds himself set up for murder and then rescued by the same mysterious blonde who set him up. The dead woman’s instructions about the case lead Max to her senile old employer Oliver Arthur Finch who denies hiring Max. Yet, the $100,000 concealed in the music box makes Max think differently. When Oliver’s alcoholic son Melrose’s girlfriend turns out to be Max’s blonde tormentor, Max know the motive for the woman’s murder may be right in the Finch family. When the blonde spins another tale, this time of blackmail, Max almost is killed on the streets of Tijuana. A second dead body appears in a hotel, then disappears just as fast, and Max finds himself on step ahead of Lt. Clapp as the two try to avoid spoiling Christmas with these murders. When the case wraps up on Christmas morning there are enough twists and turns to entertain any mystery reader. Part of the action of this novel is set in the fictional town of Point Loma, as well as the familiar San Diego and Tijuana locations. A homage to The Maltese Falcon, the book is equal in pace and characterization, but not quite the equal in plot to Hammett’s work. Yet, because it is powerful piece of hard-boiled writing, I am willing to call this a classic in the field. CALAMITY FAIR (Farrar, 1950) takes place in August. Max has returned to work as a P. I., and charges his client $25 a day plus expenses. He now employs a Telephone Secretarial Service. Although he still has a relationship with Merle, he sleeps with Quincy Day from the Night and Day Agency. Max knows his client is a phony but he cannot resist trying to recover the gambling debts of “Irene Whitney.” Things heat up when gambler George Papago’s body is found dead in an alligator pen, with Max having just spent the evening hunting for George. Hiding his involvement from the cops, Max begins to follow the trail left by blackmailers who love to use things like gambling debts to plague their victims, bleeding them dry. This plan puts Max up against San Diego D. A. Leslie Benedict, an extremely honest man who still resents Max for the killings that occurred in earlier books in the series. Although the flavor of the period comes through loud and clear, the plot’s attempt to be convoluted is so forced it becomes irritating. A weaker effort in this series, this can just be rated average. MURDER CHARGE (Farrar, 1950) takes place in November, and Max admits to being in his mid-thirties. Mob front man Harry Blue gets shot in San Diego and he is hospitalized. Lt. Clapp, D. A. Benedict, and the F. B. I. think Max should impersonate Blue from them. Blue is in San Diego for unknown reasons, and with Max’s impersonation the police could nip any mob action in the bud.  What makes this book so good is that Max must betray all that he believes in order to become Blue, including his reporter girlfriend Merle. The authors allow Max to find it too easy to be bad, and one characters says, “I think you’ll get by as Harry, all right. That same nose – and that same cold something about both of you.” This is hard-boiled noir at its best, with a false identify, a limited amount of time to solve the crime, ravenous women, and death. After the disappointment of the last book in the series, this book comes roaring back to be highly recommended. SHOOT TO KILL (Farrar, 1951) takes place in October, and Max admits to being less than forty. Max’s business has expanded and the frosted name on the glass door of his office now says, “Seaboard Investigation Service.” He employs four part-time ops. It is a sad day when Max discovers his girl Merle Osborn is dumping him for Bliss Weaver, one of Max’s clients. The night the trio becomes a duo, Bliss’s wife is strangled. Max, who had been tailing Bliss out of jealousy, tries to strengthen the evidence against Bliss by adding something to the crime scene. Caught in the act by his cop friend Lt. Clapp, Max must spend the entire novel redeeming that rather incautious act. As hopeless an effort as ever told in the hard-boiled canon, it is almost reminiscent of the same decent Max made in Guilty Bystander. The irony of Max’s situation, so important to the idea that every noir protagonist is responsible for making the one bad decision the sends them down the wrong path, finds Max eventually beginning to believe that Bliss may be innocent. This highly recommended title is sadly the last in a series that is certainly worthy of being ranked as a worthy successor to Hammett and Chandler. Asked to write something on Wade Miller’s Max Thursday novels, I realized that it had been nearly thirty years since reading my way through the series. I was a beginning writer and somewhere on the writer’s grapevine I had heard that the Thursday novels were worth seeking out. My lingering memory was of a series well-written, very hard-boiled but with a hero that I vaguely recalled being “distant.” Looking up Wade Miller in Twentieth Century Crime and Mystery Writers, Edward Hoch notes that “…it’s odd that virtually no attention is given to the early works of Wade Miller. Certainly Miller’s private eye, Max Thursday, is not in the same class as Spade, Marlowe, and Archer, but he is still someone worth knowing, and his six cases, written during a five-year period (1947-1951), are still a pleasure to read.” In revisiting the series I hoped to discover clues why the series was not better known. Before returning to the series, I read what Hoch had to say about the duo’s first novel Deadly Weapon (1946) which he called “excellent.” The novel features San Diego police Lt. Austin Clapp, a mainstay of the Thursday series. This became my starting point as I had a copy of the novel, unread over the many decades. There was one more Station of the Cross to touch before beginning. I turned to The Anthony Boucher Chronicles, Reviews and Commentary 1942-1947, Volume II: The Week In Murder edited by Francis M. Nevins. Here is Boucher’s review of Miller’s first novel as published in the August 18, 1946 issue of the San Francisco Chronicle: “Burlesque house and marihuana racket

shape

background to San Diego murder starring private eye Walter James and

police lieutenant Austin Clapp. Machinegun tempo, tight writing,

unexaggerated hardness and unorthodox and overwhelming ending mark

highly satisfactory debut of new publishers and new writing team.”

Hoch also said that the book’s ending was “unique in the private-eye genre.” Snatching up my copy of Deadly Weapon was like grabbing hold of a line of 110 house current. It may not kill you but you can’t turn it loose no matter how hard you dance and shake. Quickly it seemed to me that Hammett was the model here. The Hammett of The Maltese Falcon, as Atlanta private eye Walter James lands in San Diego on the trail of his partner’s killer. It was apparent that modern readers would need to overcome instinctive reactions to racial and other slurs. This is a novel written in 1946 featuring people with the attitudes and language of the times. In addition to the racial slurs the cast of characters includes a lesbian couple and writing today the descriptions would be quite different. Notwithstanding the fact that Walter James punches out one of them, the two lesbians do come through as very human characters. The pace is hell-bent and galloping along I tried my best to anticipate the boffo ending. Even tipped that magic was about to happen, I guessed wrong. This was a stunning debut novel. It would be a shame if the language of the times kept it from revival. Let’s turn to the first Max Thursday novel Guilty Bystander (1947) and begin again with the review by Anthony Boucher: “Ex-detective Max Thursday pulls himself

out of

alcoholism to rescue the kidnapped son he has never seen, tangling with

every sinister aspect of the San Diego underworld to do it. Less

startling than Miller’s first but a sound, meaty hardboiled

novel.” (April 6, 1947)

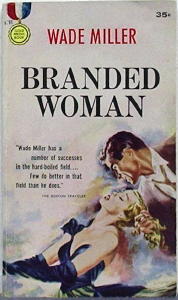

A good assessment although incorrect to say Thursday had never seen his son. He busted up with the mother when the kid was 18 months old and had not seen him since. The novel opens with his ex-wife seeking out Thursday in the flop-house hotel where he works as a house detective. Their son has been kidnapped. The boy’s stepfather is a doctor off to a convention. Warned against contacting the police, the mother turns to Thursday. The description of Thursday as a drunk is unsparing and immediately it appears that trusting him was a bad mistake on the mother’s part. Quickly the police are involved because of Thursday’s loose tongue. Before that Thursday goes to the medical practice of the missing husband (and he quickly is missing) and meets with his doctor partner. This is very early in the novel and oddly the doctor greets Thursday with a drawn pistol. It is apparent this doctor is very involved in whatever schemes resulted in the kidnapping. Along the way Thursday is aided by the owner/proprietor of his flophouse hotel, a middle-aged woman named Smitty, who clearly loves Thursday. In fact, everyone seems to end up at this hotel at some point or other.  Guilty Bystander is a very good novel and stands up quite well to the fifty-plus years that have passed. It is also a ground-breaking novel in that it is a very early example of the overtly flawed private eye hero. Now it is something of a cliché as Lawrence Block’s Matt Scudder and Tucker Coe’s (Donald Westlake) Mitch Tobin and a host of lesser imitations have come along. Most of the flawed heroes have a solid “back-story.” Not all of these “back-stories” are sympathetic. For example, Mitch Tobin was traumatized when he was laying a woman while his partner answered a call without backup and was killed. This isn’t sympathetic but it is very human and understandable. The depiction of Thursday as an alcoholic is acutely realistic. He is not someone anyone would choose to associate with – an angry, disheveled drunk. His reasons for going down into alcoholism would seem inadequate to the average reader. When Thursday returned from World War II service, San Diego was crowded with private eyes, yet his wife refused to move from the city to some location where PI prospects were more promising. So Thursday drinks himself so deeply into the gutter that he does not bother to attempt to maintain a relationship with his young son. The average reader might well say “Suck it up, big boy. If you are that tough, you should find a way. Even if you flounder professionally, why couldn’t you find a way to maintain contact with your son?” No, Thursday simply dives into the bottle. And here is the final deciding point: Is Thursday at all regretful? Not that I can tell. Oh, he reluctantly sobers up and gets his butt in gear but his son remains an abstract goal more than anything he feels on a gut level. What is more realistic: Mitch Tobin’s human failing or the inexplicable abandonment of family by Max Thursday? Drunks are usually inexplicable, causing great havoc among those that love them for no reason anyone can fathom. The writers do nothing to make Thursday more easily accessible to readers. In the words of a great George Jones song about drunks, Wade Miller delivers “The Cold, Hard Truth.” So let us examine why, as various critics have wondered, the Max Thursday series is not better known, more appreciated, and – most of all – reprinted. My mind was buzzing around this problem when I read something the late (and much lamented) William DeAndrea wrote in his Edgar winning Encyclopedia Mysteriosa (1994). After praising the series, DeAndrea said “Better appreciated by other mystery writers than by the public…” As I discovered the series as a novice writer seeking advice from the more experienced, there is an underground appreciation of the Thursday novels. It is odd that they are not, as Hoch noted, more appreciated by academics. I do think I understand why the novels have not been a bigger public hit and revived more often.  The fundamental problem is that readers do not connect with Thursday on any personal level. Take his exact contemporary Mike Hammer. Some readers identified with the avenging angel of Mike Hammer but even those that did not, understood and “believed” in the avenging character. Hammer is “real” even to those repelled by the character. Thursday is a drunk and there are no soft edges to his alcoholism. Readers are given nothing on which to hang any understanding, much less sympathy. It is realism that may be too acute for many readers. Let’s look at the final Thursday novel Shoot to Kill (1951). The authors are continuing to break tradition and push readers into areas not generally visited by the PI hero. The novel introduces an unpleasant client and then quickly Thursday learns that he is being dumped by his girlfriend of four years for this jerk of a client. This is very much turning the concept of the PI hero on its head, although it is very realistic. The humiliation of Max Thursday is unsparing and all the more startling for readers seeking hero wish-fulfillment. So even as the authors abandoned Thursday, they continued to experiment in the series until the very end. It may be this very trait that makes the series so well-remembered by writers but less admired by the average reader. First up: Bill Crider  One of the things I like about eBay is that now and then (not nearly often enough, however) I run across a book that fills a long-time gap in my collection This happened a few weeks ago when a copy of Dale Wilmer’s Memo for Murder turned up. It’s a Graphic Books original from 1951, and I wasn’t about to let it get away, as it was the only pbo by the Wade Miller duo that I didn’t already own. Naturally I was expecting some good reading, and I wasn’t disappointed. The narrator, C. O’John, is a private investigator. Or at least that’s what he calls himself. He’s sort of the anti-Philip Marlowe in that he’s an ex-cop who’s using his PI license as a cover for his real occupation as a blackmailer. Everyone calls him Johnny because he hates his first name (Chapman) and never tells anyone what it is. (This turns out to be a major plot point.) The setting is Hollywood, always a good place for decadence and blackmail, and there are some dandy scenes with a young woman named Autumn, who’s about as decadent as they come. There are a couple of other young women, too, and O’John becomes involved with all of them in one way or another. There’s a murder, of course, and before he solves it, O’John absorbs an incredible amount of punishment, and there’s a harrowing scene involving dental torture. I thought William Goldman had invented this particular tactic in Marathon Man, but Wade and Miller were a couple of decades ahead of him. (I wouldn’t be at all surprised to find out that Goldman had read Memo for Murder in his formative years.) O’John seems to be working toward some sort of redemption for himself by the end of the novel, but we’re left to wonder whether he finds it or not. I’m certainly glad I finally got a copy of this one, even if I never did figure out what the title had to do with anything in the book. Ted Fitzgerald handles the next three: Every summer, I strive to pull a few of those Gold Medals off the shelf and actually read them. This past year, as it happens, I went on a Wade Miller kick. Not the Max Thursday novels, which I read years ago, when they were reissued in trade paperback, but the stand-alones. Their first novel, Deadly Weapon (Farrar & Straus, hc, 1946) is one of the all-time great private eye novels, with a fantastic twist. I re-read it last summer and it still holds up, even knowing how it comes out. In fact, I appreciated it more, admiring how well the writers cloaked their story.  DEVIL MAY CARE (Gold Medal, pb, 1950) Aptly titled. Biggo Venn is a soldier of fortune currently without a war, reduced to giving ten dollar lectures to libraries to earn eating money. In Cleveland, he’s approached by Dan’l Toevs, a former comrade now too old and weak for the game, who offers Biggo a chance at an easy $20K. All he has to do is go to Ensenada, Mexico and snag a copy of a deathbed confession that will exonerate a deported mobster and allow him to legally re-enter the USA and take back his rackets. There are, of course, parties who do not wish this to happen. Once in Mexico, Biggo finds his contact murdered. Then he s mickey-finned by a B-girl, framed into the hoosegow by an old adversary, shot at, bested in a fist fight, rescued from jail by a beautiful young woman with whom he falls in love. There’s a lot of “What the hell?!” attitude in this fast-moving book, but there’s also subtle humor beneath its brawny approach, provoking smiles instead of guffaws. Biggo reads the Bible, not for religious reasons, but to study the battle tactics of the Old Testament warriors. It’s almost a burlesque at times, but one with a serious undercurrent. For, in the course of his adventures, Biggo – duped, drunk, doublecrossed and disillusioned – undergoes a change, questions his age and abilities and life’s work. This would have made a great Robert Mitchum movie at the time. STOLEN WOMAN (Gold Medal, pb, 1950) La Mujer Robada (The Stolen Woman) is a nightclub in the border town of Mexicali. Burke is the American piano player who’s also tickling the ivories of the owner’s wife. Burke accidentally kills her husband when he unexpectedly returns while Burke is in bed with the missus. A crooked Mexicali cop blackmails Burke into taking a package across the border into the US. The fun really begins when an American narcotics agent spots Burke and begins to squeeze him for his own purposes. The narc wants Burke to play along in hopes of identifying “Uno,” the Mr. Big of a local dope smuggling racket. Burke is then approached by and attracted to the daughter of a prominent Mexicali physician. As things develop, Burke is used and doublecrossed by just about everyone, secrets are revealed, the dead come back to life and Burke falls in love a couple of times. Ultimately, Burke confronts his destiny, assigns value to something, messes up the dope racket and delivers a body blow to the book’s ultimate bad guy. Stolen Woman is more ambiguous than Devil May Care, but in both books, an American journeys across the border finds his assumptions challenged and reappraises his life and world view. And once again, the story is told briskly and colorfully.  BRANDED WOMAN

(Gold Medal, pb, 1952) BRANDED WOMAN

(Gold Medal, pb, 1952)As good as the first two books are, this is the money shot. Certainly an early example of a story with a hardboiled woman protagonist. Cay Morgan is a con artist who, five years earlier, ran afoul of a faceless smuggler known as The Trader who punished Cay by branding a small “T” into her upper forehead. Now, Cay’s tracked one of his henchmen to Mazatlan in hopes of identifying, then killing, The Trader. Things go awry: she’s attacked, loses her gun, is kidnapped, drugged, dropped in the ocean and rescued by a broken-down fisherman who becomes the first man to penetrate her defenses. Her associate is murdered, she allies herself with a variety of blackguards (including a roadshow version of Casper Gutman and Joel Cairo), nearly gets killed again and falls in love. She ends up exiled to a remote village but returns to an island off Mazatlan to locate hidden gold and wreck cold vengeance on The Trader. The familiar elements are here: threats, double-crosses, the dead coming to life, betrayals, but Miller leaves the most shocking twist for the book’s final paragraph, a development that, depending on your point of view, is either enormously frustrating or haunting, and suggestive of an intriguing sequel Miller never wrote, as far as I know. As noted above, this book is remarkable, especially in its time, for presenting an unapologetic, hardboiled heroine. To be sure, Cay softens in spots, falls in love. She even gets rescued, but you never once think of her as a victim. She gives as good as she gets. Pretty much everything that happens to her – every attack, betrayal, assignation – mirrors what would happen to a man in a similar story. Yet she never surrenders either her toughness or her femininity. And when it comes time to settle accounts ... let’s just say that guys like Jack Reacher could learn a thing or two from Cay Morgan. Wade and Miller were unusually perceptive in their portrait of this woman. (Did their wives vet the manuscript?) This is a book worth rediscovery. Read in close order, the three books highlight certain themes and motifs the authors returned to time and again: a focus on shadowy masterminds, dope rings, respected physicians with beautiful daughters, spurious deaths, doublecrossses extraordinaire, and dandy twist endings. What a pleasure these guys are to read.

Q: Did your experiences from military service during World War Two influence your writing in the late 1940s and into the 1950s? How might it have directly or indirectly shaped your prose style or the themes that you chose?  RW: WWII influenced

my career profoundly, probably more than any other single event in my

life. I spent two and a half years in combat situations,

participating in two amphibious invasions (North Africa as a rifleman

with the 1st Infantry Division, Southern France as a member of a bomber

crew), served on a counter-intelligence team in Tunisia and Sardinia,

and covered the air war in the Mediterranean as an Air Force combat

correspondent. From those varied vantage points, I was privileged

to observe men under extreme stress and witness the many faces of

courage, all experiences which served me well in my future writing. RW: WWII influenced

my career profoundly, probably more than any other single event in my

life. I spent two and a half years in combat situations,

participating in two amphibious invasions (North Africa as a rifleman

with the 1st Infantry Division, Southern France as a member of a bomber

crew), served on a counter-intelligence team in Tunisia and Sardinia,

and covered the air war in the Mediterranean as an Air Force combat

correspondent. From those varied vantage points, I was privileged

to observe men under extreme stress and witness the many faces of

courage, all experiences which served me well in my future writing.Q: You have mentioned your admiration for Raymond Chandler whom you also knew. Could you elaborate on how he was influential on you as a writer, both as Wade Miller and in your solo work? Are there other authors that you think you learned from? RW: I fell under the influence of Raymond Chandler early, and he, along with Dashiell Hammett and the films of Alfred Hitchcock, did the most to shape my writing – Chandler for his marvelous style, Hammett for his hardbitten realism, and Hitchcock for his plot construction. Of course, all writers learn from other writers, so there are a number of other names I could add to the list, including (but certainly not limited to) James M. Cain, Horace McCoy, Cornell Woolrich and Dornford Yates. Q: In your collaborative literary efforts with Bill Miller, can you tell us why it was so solid and successful? Did you, for instance, complement each other’s strengths and weaknesses? RW: The Wade Miller collaboration worked successfully largely because it began so early. We teamed up at the age of 12, the beginning of our formative years. Added to that is the fact that we would have been close friends even if writing had not been our special bond. We shared similar tastes, enjoyed each other’s company and respected each other’s ability. Each of us exercised the power of the veto without arguments or hard feelings. We deliberately did not compartmentalize our work (e.g., one plotting, the other writing), knowing that there would come a time when one of us would have to be able to do it all. Sadly, that time came much sooner than anticipated but – thanks to our foresight – I was able to continue alone. Q: How did Mr. Miller and yourself create the various pseudonyms your titles appeared under? How did you arrive at such colorful titles, like Kitten With A Whip? RW: Throughout our pre-war writing (newspapers, magazines, plays, radio, etc.) we used Wade & Miller for our byline. When we sold our first novel, Deadly Weapon, the publisher asked for a single author’s name – so we dropped the &. Later, when we wanted to diversify, we stuck with WM and created Whit Masterson. Dale Wilmer and Will Daemer are anagrams for Wade Miller. We would have preferred Earl Mildew but couldn’t convince others. As for our titles, we bounced possibilities off each other until one stuck.  Q: Mr. Miller died tragically young at

41. What can you tell us about him as a man and as a

writer? Did he do any writing under just his name? Q: Mr. Miller died tragically young at

41. What can you tell us about him as a man and as a

writer? Did he do any writing under just his name? RW: Bill was the most intelligent, witty and talented man I’ve ever known. His interests were wide ranging and his curiosity was boundless. He was also a shy and introverted man who preferred the company of a good book to that of others. However, those close to him found that he was great fun to be with. Writing did not come easily to him; he was a perfectionist who labored over every word. But what he produced was choice. Q: How where the PI Max Thursday series received critically? What did you think of the film version of GUILTY BYSTANDER, and did Zachary Scott, who played Thursday, come anywhere near their conception of the character? Why did you decide to stop writing the series after six books? RW: The Thursday books were reviewed enthusiastically by most critics. There must have been some negative voices raised – there usually are – but I can’t recall them. Of course, it could be selective amnesia. At the time that GUILTY BYSTANDER was filmed (1949), the motion picture code forbade depiction of the kidnapping of a minor child. Since that was at the center of the story, the producers were faced with a problem they could not solve. The result was a nearly incomprehensible and thoroughly unsatisfying movie. Even a strong actor would have had a tough time bringing Thursday to life – and, alas, Zachary Scott was not a strong actor. He probably did the best he could under the circumstances but he came across as something of a wimp – which was certainly not our conception of dear ol’ Max. As for ending the series, we simply became bored with doing the same thing over and over. We wanted to escape the straitjacket a series imposes, to experiment with different kinds of stories and different kinds of characters. To us, a story in which the protagonist doesn’t face a major crisis and achieve some kind of catharsis was unsatisfying – and how many major crises can one man face before it becomes ridiculous? A few series writers – Bill Pronzini is a prime example – have handled that problem skillfully but most, in my opinion, fall into a rut, fail to grow and so never reach their true potential (but they do make more money!). Q: Did you know fellow Gold Medal writer Charles Williams either professionally or personally? Were you ever in touch with such crime writers like Charles Willeford or Richard S. Prather? RW: I didn’t know or communicate with either Charles Williams or Charles Willeford; I know them only from their work. I did correspond sporadically with Dick Prather, but I met him only recently at a paperback book signing event. Q: Can you tell us how paperback writers were generally received by critics in the 1950s? Did mystery critic Anthony Boucher, for instance, review the Wade Miller oeuvre? RW: Authors of original paperbacks were almost universally ignored by the mainstream critics. Top reviewers such as Anthony Boucher, Will Cuppy, James Sandoe and others were happy to review Wade Miller in hardcover but paid no attention to Wade Miller in original softcover. This literary snobbery was especially evident when it came to the Gold Medal Books, which pioneered the original paperback movement. A joke popular among those who labored in the GM vineyard: “Don’t tell my mother that I write for Gold Medal. She believes I’m a pimp.”  Q: What books of yours do you find most satisfying? Are there any of your novels that you don’t like as much now, looking back on them? Which books were the hardest to write? RW: Asking this question is like asking me to evaluate my children. I love them all. Q: From your vantage point as a reviewer for the San Diego Union Tribune in your monthly column “Spadework,” what are the most striking differences that you observe between crime novels now and those from the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s? Which modern practitioners do you think closest adhere to the hardboiled, noirish tone common in the 1950s and continue that school of writing? Who are some of your favorite female mystery writers? RW: The mystery-suspense-thriller has gained considerably in respectability since the ‘50’s. With increased prestige has come better money, which has attracted better writers. In the noir field, there are a number of authors equal to the old masters, among them Elmore Leonard, Ed McBain, Michael Connolly, Bill Pronzini, Tony Hillerman, Loren D. Estleman. And we mustn’t forget the women – Ruth Rendell, Nevada Barr, Sue Grafton, Sharyn McCrumb, Marcia Muller, to name a few – who are in many respects superior to their legendary sisters of the past. Thank you Mr. Wade for taking the

time to talk to us. It was a pleasure.

_________RW: Thank you for your heartwarming appreciation of our work. This tribute to Robert Wade and Bill Miller first appeared in Mystery*File #42, February 2004. Copyright © 2004 by Steve Lewis. All rights reserved to contributors. Ed Lynskey’s overview of their career also appears online at Al Guthrie’s Noir Originals website.

YOUR COMMENTS ARE WELCOME. |