Wed 16 Apr 2008

MIKE NEVINS on Giants of Film Noir, Ellery Queen on Radio, and Richard Hugo.

Posted by Steve under Authors , Columns , Crime Films , Old Time Radio[4] Comments

by Francis M. Nevins

In the second half of March, film noir lost three giants. First and youngest was 54-year-old Anthony Minghella, who died on March 18 of a hemorrhage following surgery. The son of Italian immigrants who owned an ice-cream factory on the Isle of Wight, Minghella came to the attention of mystery lovers when he wrote the scripts for three of the early Inspector Morse telefilms: “The Dead of Jericho,” “Deceived by Flight” and “Driven to Distraction.”

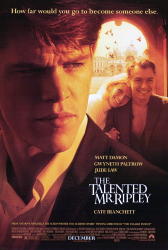

Then he moved to the big screen and made a much larger mark in contemporary noir as director and screenwriter of THE TALENTED MR. RIPLEY (1999). From Colin Dexter to Patricia Highsmith: that, friends, is range. Just before his death he had completed the first two-hour film in what may well become another series of Morse-like longevity, THE NO. 1 LADIES’ DETECTIVE AGENCY, based on the novels of Alexander McCall Smith.

Less than two weeks after Minghella’s death we lost Jules Dassin, the last survivor of film noir’s first generation of directors, who died in Athens on March 31 at age 96. Despite his name, Dassin was born and raised in New York. In the years before the McCarthy-era blacklist forced him to leave Hollywood he directed four noir classics in a row: BRUTE FORCE (1947), THE NAKED CITY (1948), THIEVES’ HIGHWAY (1949), NIGHT AND THE CITY (1950).

He relocated to Paris in the early Fifties but had to learn French before directing the celebrated noir Euro-heist movie RIFIFI (1954). He was married to Greek actress Melina Mercouri and directed her in NEVER ON SUNDAY (1960) and TOPKAPI (1964).

Between the two directors, Richard Widmark, who had starred in Dassin’s NIGHT AND THE CITY (above) and played lowlifes in a number of other noirs, died at 93. And now in the first week of April we lost Charlton Heston, who will always be remembered as the embodiment of larger-than-life figures from Moses to Michelangelo but also contributed to film noir, making his movie debut as star of THE DARK CITY (1950) and, between THE TEN COMMANDMENTS and BEN-HUR, co-starring with director Orson Welles in the superb TOUCH OF EVIL (1958).

May they all rest in peace. Their film work survives them and will outlive us too.

Thanks to Steven Slutsky, a professor of economics at the University of Florida, I recently learned of a little book that will fascinate all fans of Ellery Queen. The 107-page CHILLERS & THRILLERS was published in 1945 by Street & Smith and exclusively distributed by the Special Services Division of the Army Service Forces.

It appeared as Volume 18 of the “At Ease” series, whose purpose was “to assist the Special Service Officer, the Theatrical Advisor and all other military personnel concerned with the development of the Army recreation program.” These volumes were “not to be resold or made available to civilians.”

Pages 40 through 107 of CHILLERS & THRILLERS are devoted to three episodes of the long-running ELLERY QUEEN radio series: “The Blue Chip” [June 15/17, 1944], “The Foul Tip” [July 13/15, 1944], and “The Glass Ball” [March 23/25, 1944; based on “The Man Who Wanted To Be Murdered,” December 3, 1939].

Each episode was adapted for live impromptu staging in GI recreation halls, “with the performers reading from scripts and acting out the action without the use of scenery, costumes or props.” It was expected that these unrehearsed performances would include plenty of boners, which were supposed to “add to rather than detract from the audience’s enjoyment.”

In charge of each staging was a Master of Ceremonies, who “helps the players, prompts them and carries the action when it shows any signs of faltering. He bridges the scene changes and time passages by telling the audience what is happening. He pantomimes such actions as swimming, climbing stairs, walking, running, etc. He simulates sounds when necessary. He may in the course of a sketch become a prop, a corpse, a ferryboat, a radiator or any of a dozen things that are required for the action.”

In lieu of the guest armchair detectives of the radio series, these versions call for “a jury composed of members of the audience. These jurors should be the men in the unit who would be most amusing on the stage, such as the CO, the mess sergeant, the company clerk, and any other ‘characters’ among the men….The jury should be an odd number of men, to avoid a tie vote.”

After the GI playing Ellery announces that he knows who the murderer is, “the jurors are called onstage and polled individually… As they give their choice[s], the MC should question them on the reason for such selection….After the last juror has been polled, the jury is told that it must decide among them which [suspect] is the criminal.

“All discussion of the case takes place in front of the audience. When the MC thinks the discussion has reached the ballot-taking stage, he directs them to vote. After the vote has been taken, the play is resumed and the true solution is unveiled. Prizes are then awarded to the members of the jury who have guessed the correct culprit.”

None of the three EQ scripts has ever been published elsewhere, although “The Foul Tip” is available on audio. CHILLERS & THRILLERS is a must-read volume not only for Queen fans but also for anyone interested in how the men of “The Greatest Generation” were entertained as they fought their war.

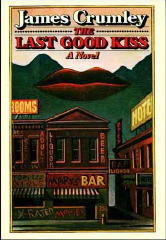

In our Poetry Corner this month is someone who – surprise! – is actually well-known as a poet. Richard Hugo (1923-1982) published his first volume of poetry in 1961 but remained unknown to the mystery-reading world until the appearance of James Crumley’s THE LAST GOOD KISS (1978), one of the finest private-eye novels ever.

Crumley dedicated the book to his friend and fellow Montanan, whom he called the “grand old detective of the heart,” and took its title from Hugo’s “Degrees of Gray in Philipsburg” (“The last good kiss/you had was years ago”).

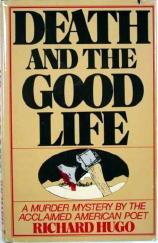

Hugo made his own pass at the crime genre with DEATH AND THE GOOD LIFE (1981), whose protagonist Al Barnes is a cop, based in western Montana but stopping over in Portland to look into the one ax murder that a recently apprehended serial killer didn’t commit.

Some cop! Overwhelmingly gentle, optimistic about human nature, feeling guilty for the world=s woes, a klutz at police procedure (his idea of a Miranda warning being “You’re under arrest. You know your rights because you’re rich.”), Barnes is de facto a variant of Ross Macdonald’s Lew Archer, a PI investigating a crime of the present with deep psychological roots in the past.

Hugo’s prose is less colorful than Crumley’s and his plotting more complex, but he shares his friend’s genius for creating softly quirky incidental characters, like the tough Homicide captain and the wily criminal-defense lawyer who on the side are both published poets. If he hadn’t died the year after his first novel came out he would surely have written more, with Barnes reconfigured as the Archeresque PI that he is in all but official title in DEATH AND THE GOOD LIFE.

For those who want to check out Hugo’s poetry, perhaps the best starting point is the posthumously published collection MAKING CERTAIN IT GOES ON (1984).

April 17th, 2008 at 11:15 pm

Excellent column Mike. I had forgotten that Anthony Minghella wrote scripts for the Inspector Morse tv series. Another reason why this series is of such high quality. And think of all the great movies we lost because of the blacklist. As you point out Jules Dassin directed four film noir classics in a row, five if you count Rififi. But for several years he could not find work because he was blacklisted.

April 18th, 2008 at 12:10 am

I second the compliment on this post. It was rich was information I had not known and with potential additions to the to-read list.

==============

Detectives Beyond Borders

“Because Murder Is More Fun Away From Home”

http://www.detectivesbeyondborders.blogspot.com/

April 20th, 2008 at 7:28 am

This is a fascinating post!

I had never heard of Richard Hugo, either. His book sounds like an important mystery novel.

And the EQ book is also completely new. There seem to be around 125 radio shows written by the Queen cousins, that are out of print (or never in print at all) in the modern era. One wonders what sort of mystery concepts are embedded in these works!

May 1st, 2008 at 7:31 pm

[…] credit card balance, a major reason I wanted to see him was to ask him about this photo I used in Mike Nevins’ most recent column. It’s a photo of two of the stars of the Ellery Queen radio program. Mike didn’t know I was […]