Tue 31 May 2022

by Francis M. Nevins

It began, I suppose, with Lord Peter Wimsey. Early in the Golden Age of English detective fiction between the World Wars, Dorothy L. Sayers’ first Wimsey novels created the sub-branch of the genre whose hallmarks were donnish wit, literary allusions and a contemporary sensibility. Near the end of the period in which this type of whodunit flourished, the mantle passed from women authors like Sayers to men, notably Nicholas Blake, Michael Innes and, a few years later, in the middle of World War II, Edmund Crispin.

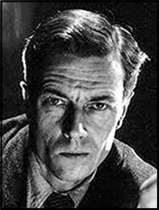

All three names were pseudonyms, the mystery-writing bylines of gentlemen with other careers. Blake, the one we are following today, was equally well known as C. (for Cecil) Day-Lewis (1904-1972), who along with his friends W.H. Auden and Stephen Spender was ranked among the foremost young poets of the post-WWI generation. Lovers of that form of literature remember him as England’s Poet Laureate from 1968 until his death, and for movie buffs he’s perhaps best known as the father of actor Daniel Day-Lewis.

I can’t remember when I began reading Nicholas Blake novels or even whether it was before or after we read the Day-Lewis translation of the Aeneid in high school. In any event it was generations ago. Recently I decided to revisit Blake and see how his work stands up today.

His debut novel, A QUESTION OF PROOF (1935), opens at Sudeley Hall, a preparatory school of the sort in which Day-Lewis spent several years as an instructor. Of the eighty-odd boys that it houses, the richest and most despised is Algernon Wyvern-Wemyss. His classmates refer to him as a squit and a worm, and if THE WIND IN THE WILLOWS hadn’t taught Brits to love the sweetly singing little amphibian known to biologists as Bufo bufo, no doubt they would have called him a toad.

On the end-of-term day when the inmates’ parents are invited to the school for fun and games, this young fiend is found strangled to death inside a hollow haystack which a few hours earlier had been the scene of a passionate rendezvous between one of the school’s instructors and the lovely young wife of its pedantic and tyrannical headmaster, who is also the dead boy’s uncle and only living relative.

Could the lovers have been caught in the act by the kid, and could one or both of them have strangled him to keep his mouth shut? There are of course more than two suspects, including some other instructors and the headmaster, who inherits most of his swinish nephew’s money. (With his complete lack of interest in law, Blake does nothing to explain how this came about.)

But the young man who visited the haystack is so deeply under suspicion that he sends to London for his old Oxford friend Nigel Strangeways, a Holmes-like consulting detective.

At first Nigel comes across as something of a silly-ass character, demanding endless cups of tea, singing an aria from Handel’s ISRAEL IN EGYPT during a wild auto chase (the first of many physical action scenes in Blake novels), submitting to a schoolboy secret society’s initiation rite that involves, among other things, putting a chalk mustache on the statue of a “nimph†in the village square.

But most of the time he plays his detective role well, preferring psychological to physical clues (of which there are none), recognizing that one unanswered question—why was the dead boy not seen by anyone in the hour or so before his death?—is the key to his murder.

When a second murder takes place, a stabbing with an improvised stiletto during a cricket game between the students and their fathers, he concludes that the answer to another question—how was the stiletto made to disappear?—will solve both this crime and the earlier one. For Yanks there may be a bit too much schoolboy and cricket jargon but on the whole this is an excellent debut novel, deserving all the accolades it has garnered since its first publication.

The title of the second Strangeways exploit and much of its plot are taken from an obscure (except to specialists) Jacobean melodrama. THOU SHELL OF DEATH (1936) is a quotation from Cyril Tourneur’s THE REVENGER’S TRAGEDY (1607), a play which becomes increasingly relevant as we progress through the book.

On a recommendation from his uncle, an Assistant Commissioner at Scotland Yard, Nigel travels to rural Somerset a few days before Christmas to investigate three threatening letters that have been sent at the rate of one a month to Fergus O’Brien, a World War I air ace who, somewhat like Lawrence of Arabia, has retired to the countryside.

The most recent letter prophesies that O’Brien will die on the day after Christmas, also known as Boxing Day and the Feast of Stephen, the day on which good king Wenceslas in the carol went out. The reclusive war hero is uncharacteristically hosting a house party over the holidays, a party consisting of a woman explorer whose life he had saved in Africa, her financially desperate brother, a shady roadhouse proprietor, O’Brien’s discarded mistress, and an old Oxford don who had been one of Nigel’s professors.

Sure enough, O’Brien is found shot to death on Boxing Day morning, and over the next few days there’s another death, this one by poison inserted in a peanut, and a near-fatal bludgeoning. Many chapters are filled with complex alternative theories of the crimes, propounded by Nigel and a Somerset officer and Inspector Blount of Scotland Yard, but the reasoning remains on a speculative level until Nigel travels to rural Ireland in search of O’Brien’s mysterious pre-war past.

SHELL is more of a full-blooded detective novel than A QUESTION OF PROOF, with a particularly brilliant “player on the other side†(although how this adversary came to know so much about the works of Cyril Tourneur remains unexplained) and abundant quotations and allusions ranging from the tale of Hercules and Cacus and the epistles of St. Paul through Shakespeare (and of course Tourneur) and finally a few of Day-Lewis’s contemporaries.

Nigel no longer guzzles tea by the potful as he did in his first outing but at one point, having missed his dinner, he snarfs a gargantuan impromptu meal—a pound or so of cold beef, ten potatoes, half a loaf of bread and most of an apple pie—-and later, just as in A QUESTION OF PROOF, he breaks into song during a wild auto chase.

American readers might be put off by the number of minor characters who speak in regional or ethnic dialects as if they were in a Harry Stephen Keeler novel, but at least the accents are more authentic than the ones HSK dreamed up. (*)

The poisoned peanut in the second Blake novel is (dare I say it?) a mere bag of shells compared with the murder method in the third. There were signs in that second book that Nigel was beginning to fall in love with Georgia the daredevil explorer. At the start of THERE’S TROUBLE BREWING (1937) they’re married. Nigel is still a consulting detective but has developed a sideline as an authority on poetry, and on the basis of his book on the subject he’s invited to deliver a lecture before the Literary Society in the Dorsetshire town of Maiden Astbury.

The Big Daddy of the place is the owner of the local brewery, whom, if I weren’t so fond of Bufo bufo, I’d describe as a toad of the first water. He bullies his wife and all but cuts her out of his will (which I don’t think possible under either English or American law, but we’ve seen before that Blake has zero interest in legal issues).

He also sexually harasses young women, requires his laborers to work inhuman schedules, makes life hell for his socially conscious younger brother, blackmails into silence the local doctor who has documented the brewery’s unsafe working conditions. He even beats his fox terrier! It’s because of this dog, who was found two weeks earlier in one of the brewery’s pressure vats, literally boiled to death, that the Big Daddy character prevails on Nigel to stay in Maiden Astbury for a while and investigate the animal’s murder.

Nigel spends the next day touring the beer factory and interviewing its principals but his detection is interrupted by the discovery inside the same pressure vat of a human skeleton, apparently that of Big Daddy, although Nigel and the local police inspector seem to be familiar with Conan Doyle’s THE VALLEY OF FEAR and the early Ellery Queen novels since they seriously consider the possibility that the boiled corpse is someone else.

Suspicion spreads among various characters and several highly speculative alternate theories of the crime are articulated. In due course come two more murders and a midnight climax in the eerie brewery that may remind some readers of a 1930s cliffhanger serial, although Blake is careful to keep Nigel from acting like a serial hero.

With each chapter prefaced by a literary quotation—from Shakespeare and Bacon and Ben Jonson through 19th-century figures like Byron and Coleridge and Dickens to the poet A.E. Housman, who had died in 1936—this is a fine example of the kind of detective novel whose earliest protagonist was Lord Peter Wimsey.

Blake’s fourth novel was the only book of his that became the basis of a feature-length film by a prestigious director. I’ll discuss both the book and the movie when I return to Blake later this year. His fifth novel was almost made into a movie by another prestigious director—or more precisely by a young man who quickly became one of the most prestigious directors of all time. When I take up Blake again I’ll tell that story too.