May 2007

Monthly Archive

Wed 30 May 2007

A few posts back, mystery writer George Marton was discussed, this in conjunction with my comments on the movie based on a thriller mystery he co-authored with Tibor Méray, Catch Me a Spy.

I listed there the books he had to his credit in Crime Fiction IV, a list that’s repeated below. I also pointed out he was born in 1900, but that no year of death had been noted, and that that was all I knew of the man.

Thanks the investigative endeavors of Victor Berch and Ted Murphy, working separately, I can now tell you more. First, a repeat of George Marton’s entry in CFIV, adding his year of death and correcting his year of birth.

MARTON, GEORGE (1899-1979)

* The Raven Never More [with Tibor Méray] (n.) Spearman 1966.

* Catch Me a Spy [with Tibor Méray] (n.) Allen 1971; Harper, 1969.

* Three-Cornered Cover [with Christopher Felix] (n.) Allen 1973; Holt, 1972.

* The Obelisk Conspiracy [with Michael Burren] (n.) Allen 1975; Stuart, 1976.

* Alarum (n.) Allen 1977

* The Janus Pope (n.) Allen 1980; Dell, 1979.

While the books above all fall generally into the category of spy fiction, I’ve yet to come up with much in terms of story descriptions — and this is rather surprising — nor have I found scans of any of the covers, not one. Both of these omissions will be taken care of in a later post.

His full name was George Nicholas Marton. Born June 3, 1899, in Budapest, Hungary; died April 13, 1979, in West Hollywood, California. Of the Jewish faith, Mr. Marton earned a PhD from the Sorbonne in 1924 and was a internationally known literary agent in Vienna between 1925 and 1937, and in Paris from 1937 to 1939.

Fleeing the Nazis and coming to the US aboard the SS Normandie on March 30, 1939, he became president of the Playmarket Agency in Los Angeles from 1939 to 1944, later working for MGM. During World War II, Mr. Marton served in the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) and the National Guard. Returning to Paris, he became the literary agent for 20th Century Fox in Paris until his retirement in 1963 or 1969. (There are conflicting dates given for the latter.)

It was not until his retirement that he turned seriously to writing. Besides the film based on one of his novels, one other, Play Dirty (1968), came from an original story he wrote. The movie, a “Dirty Dozen” type of war drama, was directed by André De Toth and starred Michael Caine in the leading role.

His final novel, The Janus Pope, did not appear until after his death from cancer at the age of 79.

Wed 30 May 2007

JOHN SPAIN – The Evil Star

Popular Library 239, paperback reprint; no date stated [1950]. First Edition: E. P. Dutton, hardcover; April 1944. Digest paperback reprint: Detective Novel Classic #44 [date?]. Magazine appearance: Thrilling Mystery Novel Magazine, Spring 1945.

The detective in charge of the case that develops in The Evil Star is Lt. Steve McCord, a member of the Los Angeles Police Department, Homicide Detail. Cleve F. Adams, noted pulp fiction writer who wrote a tidy sum of hardcover novels as well, wrote three novels as by John Spain. The other two featured a private eye named Bill Rye.

The link will take you to Kevin Burton Smith’s Thrilling Detective website, where you will, if you wish, learn more about a couple of other PI’s, one named Rex McBride (five novels), the other John J. Shannon (two books). From Adam’s pulp days but no stories in book-length form, Kevin also has an entry for Violet McDade & Nevada Alvarado, two very early fictional private eyes in the overall scheme of things (seven novelettes in Clues Detective Magazine between 1935 and 1937).

Since these detectives are fairly well-documented, there’s no need for me to do so, which means all the more space to discuss the book at hand. (The rundown in the paragraph above does not include all of Adams’s novels, however. Perhaps I’ll get back to some of the rest of his fiction sometime soon.)

This is a complicated case, and I won’t even begin to try to spell anything out for you. What’s sort of unique, though, is that there are not twins involved, but triplets. Three young women named Faith, Hope and Charity, and while they live far apart and separate lives, they for some reason all turn up in LA at the same time.

Charity is a school teacher, in town for a national convention of school supervisors.

Faith is a secretary and traveling companion of an elderly woman named Gretchen Van Dorn, who is also wealthy and the owner of the Ayvil Star, said to have a curse on it. (We’ve heard that story before.)

Hope is another story altogether. She’s a bubble dancer from San Francisco who disappears from police headquarters after being brought in bruised and without her memory. She may be involved, it turns out, with the killing of a crooked LA public works commissioner named Welles up in San Francisco.

If you were to put some of the pieces of the puzzle from here, as meager as I’ve left the details, some of them, I’m sure, would fall right into place.

I might mention two other matters, though. First, there seems to be a leak in the LAPD, and McCord might be the person responsible, so most of the time he’s working on the case unofficially and on leave from the department. Secondly, and the reason he stays working on the case, is that he quickly falls for one of the sisters, and Charity in particular. Solidly and with a loud thud. So solidly that he cannot believe his good fortune, thinking that she might vanish like a piece of fog or mist in his hand. It colors his thinking, but so do various konks on the head and the killing of at least one good friend on the force.

The end result is a hard-boiled case combined with a semi-screwy caper that has aspirations of being a detective story, with an ending definitely not from Agatha Christie. From page 157 (of 159):

— [

the killer, name omitted] sighed gustily, lifted [

his/her] gun at McCord, hesitated for one brief fatal second. In that second McCord shot [

him/her] squarely in the mouth.

This never happened in a Christie novel, or did it? I haven’t read all of hers, and some of the endings in her books may have been equally tough, in a purely figurative sense, mind you. You tell me.

But to get back to John Spain’s book, it all turns out well in the end. Just in case you were wondering.

Wed 30 May 2007

CRISTINA SUMNERS – Familiar Friend

Bantam; paperback original. First printing: August 2006.

Familiar Friend is the third in a series of mystery adventures in which the two leading characters have an exceeding complicated relationship, which I will get to in a moment. First of all, however, here are the books:

Crooked Heart. Bantam, hc, October 2002; reprint pb, September 2003.

Thieves Break In. Bantam, pbo, October 2004.

Familiar Friend. Bantam, pbo, August 2006.

There is a long story behind the writing of these books and why it took so long for them to find a publisher. The author hints at it in the Acknowledgments to this one, but then she goes on to say that the story would bore us. As if. But – if I have read this introduction correctly – this, the third book, was the first one written, or at least plotted, and that was back in the 1970s when she was taking courses at Princeton, which is the town upon which her fictitious town of Harton, New Jersey, is modeled.

Harton being the home of the Reverend Kathryn Koerney and police chief Tom Holder, who are tacitly in love with each other, but neither of whom dares to admit it, even to themselves. Tom Holder is married, but to a wife he does not love, nor does she love him. Kathryn Koerney is all but committed to another man, a rich Englishman named Kit Mallowan. (From what I’ve gathered, Kathryn is equally wealthy, if not wealthier, but I can’t tell you any of the details, this being the only book of the three that I’ve read. I also gather that she met Kit in England, where Book Two took place.)

The setting in Book Three is purely academic, at least in the beginning, given that the body of the chairman of the local university’s Spanish department being found on the driveway leading into St. Margaret’s, a parish church. The man was universally disliked by his colleagues, it is soon revealed, making sure that there are many, many suspects for Holder to interview in the initial stages of the investigation that quickly ensues.

Curiously enough, however, even though all of these professors, wives, students and the staff, crew and a group of the usual university hangers-on are strongly depicted, with considerable time and energy put into making them distinct individuals (all with motives), and with all of this elaborate background already built and ready to wear, the author seems to forget about (most of) them and concentrates instead on the not-so-minor issue of mysterious disappearance of Holder’s wife, causing the local D.A. to…, and Father Mark to…, and then Kit to…

I can say no more, but it is a lot of fun. You will have to read it for yourself. Sometimes the leading characters behave like teenagers in their rather complicated dance they perform in establishing their relationships to each other, but it’s all done in such a nicely charming fashion, that I am sure that all but the most surly curmudgeon would not be pleased and object to it.

The puzzle of the mystery is classically done as well, what with time tables and the shrewdest of plans concocts by the villain(s) involved. The last line has nothing to do with the mystery (as opposed to the Ellery Queen novel I covered not so long ago), but if you care anything at all about the characters, it will make absolutely certain that you will not miss where the next episodic installment of their amusing romance (but not to them) will take them next.

[UPDATE] 05-30-07. Unfortunately, given the pattern of appearances of books in this series, it looks as though there will still be over a year’s wait.

Tue 29 May 2007

CATCH ME A SPY. [a/k/a TO CATCH A SPY] Capitole Films, 1971. Kirk Douglas, Marlène Jobert, Trevor Howard, Tom Courtenay, Patrick Mower. Based on the novel Catch Me a Spy by George Marton & Tibor Méray. Co-screenwriter & director: Dick Clement.

The particulars on the novel, as per Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin, are as follows:

Catch Me a Spy (with Tibor Méray). Allen, UK, hc, 1971; Harper, US, hc,1969.

The author twosome wrote one other book together:

The Raven Never More (with Tibor Méray). London: Spearman, hc,1966.

This is the extent of Tibor Méray’s entries in CFIV. George Marton has a small number of other books listed for him. All are hardcover editions unless indicated otherwise:

MARTON, GEORGE (1900- )

* Three-Cornered Cover [with Christopher Felix] (n.) Allen, UK, 1973; Holt, US, 1972.

* The Obelisk Conspiracy [with Michael Burren] (n.) Allen, UK, 1975; Stuart, US, 1976. [France]

* Alarum (n.) Allen, UK, 1977.

* The Janus Pope (n.) Allen, UK, 1980. Dell, US, pb, 1979.

I imagine George Marton has passed away by this time, but at the moment I have to confess that this is all I know about him.

And after all, this is a review of the film that was based on one of his books, and one I enjoyed but have rather mixed feelings about. The plot, however, should come first, and so I shall. Fabienne (Marlène Jobert), the rather naive young niece of a British intelligence official (Trevor Howard) is romanced and quickly married to John Fenton (Patrick Mower), but their honeymoon in Bucharest is rudely (if not crudely) interrupted by Fenton’s arrest and whisking off to Russia, where an exchange for a spy in Britain’s hands is demanded.

When the swap falls through (and this is meant literally), the spy the Russians wanted not being available, in order to obtain her husband back, Fabienne must find another spy to offer them instead. This is where a chap named Andrej (Kirk Douglas) comes in.

As there are in all good spy movies, there are several secrets behind some of these statements, none of which will I reveal, but after some quarreling and other small rows between the (now) two primary participants, a mutual kidnapping and several other humorous interludes, the day is saved — in a frenzy of final revelations and speedboat chases.

And I confess that I did not realize for a while that there WERE humorous interludes in this movie, and it took me several double-takes before I fully caught on. British humor is rather dry, often with a “did they really mean that?” sort of approach to comedy, at least on the viewer’s part, or so it was for me.

I should have mentioned before now that this is a British film, in spite of Kirk Douglas being a well-known American star, and Marlène Jobert being equally well-known in France, but not in the US until recently, when it was revealed that she is the mother of Eva Green, female star of the most recent James Bond movie.

But to get back to the point I was making, the movie we are talking about (and not Casino Royale) is amusing but not hilarious. It was also done in, at least for me, by accents. Both the British accents in this film, sometimes near impenetrable, and Mlle. Jobert’s French accent, often in a whispery voice, have convinced me that I might enjoy the movie even more if I were to watch it again and give them (the accents) a second try, which indeed I may.

Or not. I didn’t see the attraction between the two leads. Kirk Douglas is tall and scruffy looking, while Mlle. Jobert appears short and pixie-ish if not waif-ish. She seems to all but disappear whenever they are on the screen together, standing one next to the other. Perhaps another viewing of this film would convince me otherwise, but right now, after seeing the movie only once, I can’t imagine opposites ever attracting each other as strongly as they are supposed to have done in To Catch a Spy.

Mon 28 May 2007

Online cover scans for the Phoenix Press mysteries are now complete from 1936 through 1952, when the last of their titles was published.

Coming up next: the crime fiction published by Hillman-Curl between 1936 and 1939. Authors included in this line of lending-library mysteries include Bram Stoker, Steve Fisher, J. S. Fletcher, E. R. Punshon, Roger Torrey and many others. Look for the covers soon. You will read about it here first.

Sun 27 May 2007

Posted by Steve under

AuthorsNo Comments

The results are in. The question was, as posed by Jeff Pierce, head man at The Rap Sheet blog:

Name ONE crime/mystery/thriller novel that you think has been most unjustly overlooked, criminally forgotten, or underappreciated over the years?

With something like 100 reviewers, bloggers, fans and authors responding (some of them falling in all four categories), it wasn’t surprising to see that there was very little overlap, not only in the stories but even with the authors themselves.

One story managed to get three mentions, however:

Night Dogs (1996), by Kent Anderson

Four more stories received two nominations each:

Anatomy of a Murder (1958), by Robert Traver

Cotton Comes to Harlem (1965), by Chester Himes

Interface (1974), by Joe Gores

Night of the Jabberwock (1951), by Fredric Brown

Authors mentioned more than once (more than one title) were:

Charles Willeford, P.M. Hubbard, Ross Macdonald, Colin Harrison, and Jess Walter.

You can play a game with yourself, no prizes offered, by seeing (a) how many of the books you read, and then (b) how many of the authors you’ve read.

In my case, the answer is (a) 13 and (b) 30. After reading mystery fiction for nearly 55 years, this is bad. Down right pitiful. I demand a recount! Wait ’til next year!

Sun 27 May 2007

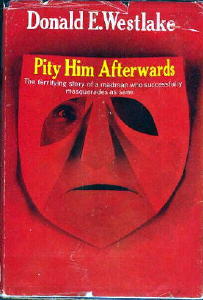

DONALD E. WESTLAKE – Pity Him Afterwards

Carroll & Graf; paperback reprint, 1996. Hardcover edition: Random House, 1964. British hardcover: T. V. Boardman, 1965 (American Bloodhound #499). Paperback, UK: Penguin, 1970.

It seems odd that there was no prior paperback edition before this one from Carroll & Graf — I’m assuming that the one from Penguin I found on ABE is a British edition. It was written at the beginning of Westlake’s career, however, and it was written just before it went in a different direction, and a terrifically successful one at that, so perhaps it got lost somehow in the transition.

Let me show you what I mean. Here are Westlake’s first five books — I’m ignoring the non-mysteries and the ones he wrote under different names. (A topic that needs some attention, perhaps, and one that if not done already by someone else may indeed be discussed at further length here someday.)

The Mercenaries, Random House, 1960.

Killing Time, Random House, 1961.

361, Random House, 1962.

Killy, Random House, 1963.

Pity Him Afterwards, Random House, 1964.

All tough guy thrillers, more or less, in one way or another.

Then came:

The Fugitive Pigeon, Random House, 1965.

The Busy Body, Random House, 1966.

The Spy in the Ointment, Random House, 1966.

God Save the Mark, Random House, 1967.

Comic capers all of them, in one form or another. And all were picked up by the Mystery Guild, as was Killy in the first grouping, but that was the only one of the five that was, and it is one that has never had a paperback edition in the US at all. (Can that be? That doesn’t seem right. But no, all I’ve found is a British PB from Penguin.)

What I am trying to say is that until he started writing the funny stuff, no one knew who Donald E. Westlake was. And then all of a sudden they did, and there wasn’t a publisher around who wanted to confuse the reader by saying, hey, here’s Westlake, and he wrote this other stuff, too.

Or I’m making this up out of nothing. It’s pure conjecture, nothing more.

It isn’t as though Pity Him Afterwards is a bad book. Far from it, and it’s about time I started the review, isn’t it?

If you remember OTR (Old Time Radio) and as a kid you listened to shows like Inner Sanctum, Suspense and The Whistler soon before bedtime, you will remember quite a few of them that began with an mad lunatic escaping from a mental institution, an asylum, a building which in my imagination had festooned with turrets and outside walls covered with barbed wire and unimaginable things taking place inside.

And a motorist comes along and gives the madman, a hitchhiker, a lift, to his everlasting regret, a regret which sometimes did not that long at all. You can pick up the story from there. As often as it happened in real life, it happened 10 to 100 times more frequently on the airwaves of the 1940s and early 50s.

I’m not sure how often it occurred in the world of mystery fiction. I do remember Margaret Millar’s The Iron Gates (Random House, 1945) as falling into the category, but no others come to mind, at the moment.

Other than Pity Him Afterwards, that is. Just like I remembered it. Perfectly. Back then it was pull-up-the-covers time, but since I’m a few years older now, no, it didn’t bother me as nearly as much as madmen on the prowl did back then, when I was a kid, lying on the floor next to the radio, my heart pounding.

Robert Ellington is one such escapee, although Westlake refers to him almost exclusively as the madman. Taking the identity of the fellow who picked him up, a young actor, the madman finds his way to Cartier Isle, and the summer playhouse where he becomes one of the troupe of players. The madman has a gift of mimicry and role-playing, and with a few well-chosen lies, he manages to fit right in. But which one of three newcomers to this season’s program is he?

He kills his first victim the second day he is on the job. Cartier Isle, a wealthy, upscale summer community, no state mentioned, has only a four-man police force, headed by Dr. Eric Sondgard, who is a mere college professor the rest of the year. It is this other half of his professional life that allows him to judge people quickly. He’s a quick profiler, in other words, but while reluctant to call in the state troopers, he soon begins to feel in over his head a whole lot sooner than he expected.

The reader may become confused right about here. Not about the story itself, which is perfectly clear, but rather the category the story falls into. A detective story, perhaps? On page 58 a detailed timetable is created, eliminating all of the people staying in the boarding house next door to the theatre except for the aforementioned three newcomers. (The idea of a wandering tramp being responsible is discarded as soon as messages from the killer are found written with soap in the bathroom and with jam on the kitchen table.)

Sondgard tries a bluff based on a fingerprint that he does not actually have, but it is a clever idea. On pages 127-128, however, he is beginning to worry that he is using the wrong approach:

Sondgard shook his head in angry irritation. It was worse than a double crostic. Worse than

Finnegans Wake without a pony. Worse than the detective books so many of his fellow professors — but not his fellow captains — insisted on writing every summer, in which the final clue came from the author’s specialty; an inverted signature in a first-edition Gutenberg

De civitate Dei, the misspelling of the Kurd word for bird, the inscription on a Ming Dynasty vase, or the odd mineral traces found embedded in the handle of the kris.

And so, no, in spite of first impressions, that’s not the kind of story it is. A thriller, then, as it started out to be? Pressured by the bluff, the killer … but no, that would be telling.

Let me go back and show you some more what kind of writer Westlake was when he was in his early 30s. Lyrical and clear, pungent and confident, a glorious let-it-all-out sort of prose, written almost with the sheer joy of writing. It may not work for everyone, but there are passages in this book that made me only sit back and quietly admire them.

For descriptive writing, from page 91, for example, and of an ordinary bar, no less, down the street from the theatre:

The facade of the Lounge was Southern plantation, complete with pillars and a veranda and white front door. But inside the disguise was dropped completely; the interior was the stock bar decor to be found anywhere in the United States. A horseshoe-shaped bar dominated the center of the room, with booths at the side walls. The normal beer and whiskey displays, with all their flashing lights and moving parts, were crowded together at the back bar amid the cash registers and the rows of bottles. Most of the light came from these back-bar displays, aided only slightly by the colored fluorescent tubes hidden away in the trough that girdled the room high up on the wall. Lithographs of fox-hunting scenes predictably dotted the walls, and the imitation gas lamps jutting from the wall over each booth said Schlitz around their bases.

With a setting such as a summer playhouse, a story works only if the author knows his way around summer playhouses, and the people who inhabit them. Westlake does, or he does well enough to convince me.

Besides having the ability to describe bars, he also knows people, including the awkward boy-girl situation in which neither quite knows what the other party is thinking. From page 167:

Mel was not at all sure of himself. Mary Ann seemed open and honest and friendly, and she had no objection to being here alone with him, but he wasn’t at all sure how much that meant. Because she was assuming more and more importance to him, he wanted to make no rash or ill-advised moves, wanted to avoid inadvertently driving her farther away from himself.

So he hadn’t yet kissed her. He’d been thinking about it, more or less constantly, ever since they’d landed here [on a small island in the middle of a lake], but as yet he hadn’t even begun a move in that direction.

He argued with himself about it, telling himself that after all she had come out here with him, and after all under circumstances like this she had to expect him to kiss her, didn’t she? But God alone knew went on in the minds of girls; she might not be expecting to be kissed at all. She might be thinking of them now as sister and brother.

On the other hand, what if he didn’t try to kiss, and she’d been waiting all day for him to make the first move? Wouldn’t that be just as bad? If she did want to be kissed, and he didn’t kiss her, wouldn’t that drive her away from him just as surely as if she didn’t want to be kissed and he did try?

It was a problem.

A problem indeed, and a universal one. A problem, you will pleased to know, is finally resolved a page or so later, ignoring the madman, the two of them in fact ignoring the world around them and working out the problem on their own.

The problem of the madman is another matter, and in a short book, only 185 pages long, the matter seems to end too quickly and abruptly. Not that I’m displeased. It’s a ending worthy of being called an ending, with only a doctor, the head of the asylum from which the madman escaped, regretting the loss of the madman’s intelligence and potential, if only he could have been cured.

The title, not so incidentally, comes from Dr. Samuel Johnson (Boswell: Life of Johnson. Entry for April 3, 1776.):

MURRAY. “It seems to me that we are not angry at a man for controverting an opinion which we believe and value; we rather pity him.”

JOHNSON. “Why, Sir; to be sure when you wish a man to have that belief which you think is of infinite advantage, you wish well to him; but your primary consideration is your own quiet. If a madman were to come into this room with a stick in his hand, no doubt we should pity the state of his mind; but our primary consideration would be to take care of ourselves. We should knock him down first, and pity him afterwards.”

[UPDATE] 05-28-07. You may be wondering why I happened to pick this review out the archives where it’s been mothballed for well over a year. On his blog a couple of days ago, Ed Gorman reviewed this same book by Donald Westlake, and if you were to stop over there to read it, it’s pretty clear that we were reading the same book. A slightly different perspective, it goes without saying, but it’s the same book, and it’s one we both think you should read (speaking for Ed without a prior consultation on doing so, but I don’t think he’s going to disagree).

Sun 27 May 2007

The following pair of posts came from the

FictionMags Yahoo group. Thanks to Bill Contento and Mike Ashley for allowing me to reprint them here. First, a short introduction from Bill:

Mike Ashley recently asked me for a list of mystery anthology publishers. As part of the process in generating that list, counts of the authors and stories in 2,244 anthologies were also produced.

This was based on the latest edition of the Mystery Short Fiction Miscellany CD (available from Locus Press), excluding stories reprinted in single-author collections, round-robin novels, and magazines.

Bill C.

Authors with 40 or more stories that have appeared in mystery anthologies:

40 Collins, Max Allan

40 Crider, Bill

41 Fish, Robert L.

41 Highsmith, Patricia

42 Sayers, Dorothy L.

43 Allingham, Margery

43 Bankier, William

43 Barnard, Robert

43 Chesterton, G. K.

43 Ellin, Stanley

43 Oates, Joyce Carol

44 Asimov, Isaac

44 Blochman, Lawrence G.

44 Brown, Fredric

46 Boucher, Anthony

46 Gilford, C. B.

46 Howard, Clark

46 MacDonald, John D.

47 Breen, Jon L.

48 Estleman, Loren D.

48 Wallace, Edgar

48 Westlake, Donald E.

49 Simenon, Georges

51 Charteris, Leslie

52 Stout, Rex

53 Holding, James

54 Deming, Richard

57 Bloch, Robert

58 Gorman, Ed

58 Symons, Julian

62 Treat, Lawrence

63 Lovesey, Peter

66 Keating, H. R. F.

67 Rendell, Ruth

69 Pentecost, Hugh

81 Block, Lawrence

81 Doyle, Arthur Conan

87 Woolrich, Cornell

88 Ritchie, Jack

89 Slesar, Henry

102 Lutz, John

103 Pronzini, Bill

115 Christie, Agatha

119 Queen, Ellery

131 Gilbert, Michael

273 Hoch, Edward D.

Stories that have appeared in mystery anthologies 10 or more times:

10 Block, Lawrence “By the Dawn’s Early Light” nv 1984 {Playboy}

10 Buck, Pearl S. “Ransom” nv 1938 {Cosmopolitan}

10 Carr, John Dickson “Guest in the House” ss 1940 {The Strand}

10 Chesterton, G. K. “Queer Feet” nv 1910 {The Storyteller}

10 Christie, Agatha “Witness for the Prosecution [ “Traitor’s Hands”] nv 1925 {Flynn’s}

10 Crawford, F. Marion “Upper Berth” nv 1886 *The Broken Shaft: Unwin’s Christmas Annual*, ed. Sir Henry Norman, London: Fisher Unwin

10 Dickens, Charles “Signalman” ss 1866 {All the Year Round}

10 Dickson, Carter “Clue in the Snow” ss 1940 {The Strand}

10 Doyle, Arthur Conan “Adventure of the Bruce-Partington Plans” nv 1908 {The Strand}

10 Ellin, Stanley “Question My Son Asked” ss 1962 {EQMM}

10 Gilbert, Michael “Amateur in Violence” ss 1949 {John Bull}

10 Gilbert, Michael “Mr. Portway’s Practice” ss 1957 {Lilliput}

10 Hardy, Thomas “Three Strangers” nv 1883 {Longman’s}

10 Harte, Bret “Stolen Cigar-Case” ss 1900 {Pearson’s Magazine}

10 Hemingway, Ernest “Killers” ss 1927 {Scribner’s}

10 Howard, Clark “Horn Man” ss 1980 {EQMM}

10 Rawson, Clayton “From Another World” nv 1948 {EQMM}

10 Rendell, Ruth “New Girl Friend” ss 1983 {EQMM}

10 Saki “Sredni Vashtar” ss 1910 {The Westminster Gazette}

10 Steinbeck, John “Murder” ss 1934 {North American Review}

10 Wells, H. G.“Cone” ss 1895 {Unicorn}

11 Barnes, Linda J. “Lucky Penny” ss 1985 *The New Black Mask No.3*, ed. Matthew J. Bruccoli & Richard Layman, HBJ

11 Bentley, E. C. “Inoffensive Captain” ss 1914 {Metropolitan Magazine}

11 Bentley, E. C. “Sweet Shot” ss 1937 {The Strand}

11 Bloch, Robert “Yours Truly, Jack the Ripper” ss 1943 {Weird Tales}

11 Chesterton, G. K.“Oracle of the Dog” nv 1923 {Nash’s Magazine}

11 Cole, G. D. H. & Margaret “In a Telephone Cabinet” nv 1923

11 Collier, John “Back for Christmas” ss 1939 {New Yorker}

11 James, P. D. “Victim” nv 1973

, ed. Virginia Whitaker, London: Macmillan

11 Kipling, Rudyard “Return of Imray” [ “The Recrudescence of Imray”] ss 1891 *Life’s Handicap*, Macmillan

11 McCloy, Helen “Chinoiserie” nv 1946 {EQMM}

11 Macdonald, Ross “Guilt-Edged Blonde” [as by John Ross Macdonald] ss 1954 {Manhunt}

11 Macdonald, Ross “Midnight Blue” nv 1960 {Ed McBain’s Mystery Book}

11 Marsh, Ngaio “I Can Find My Way Out” ss 1946 {EQMM}

11 Pentecost, Hugh “Day the Children Vanished” nv 1958 {This Week}

11 Poe, Edgar Allan “Black Cat” ss 1843 {Philadelphia United States Saturday Post}

11 Poe, Edgar Allan “Mystery of Marie Roget” nv 1842 {Snowden’s Lady’s Companion}

11 Queen, Ellery “Adventure of the President’s Half Disme” nv 1947 {EQMM}

11 Queen, Ellery “As Simple as ABC” nv 1951 {EQMM}

11 Stoker, Bram “Squaw” ss 1893 {Holly Leaves}

11 Westlake, Donald E. “Never Shake a Family Tree” ss 1961 {AHMM}

12 Armstrong, Charlotte “Enemy” nv 1951 {EQMM}

12 Charteris, Leslie “Arrow of God” nv 1949 {EQMM}

12 Crofts, Freeman Wills “Mystery of the Sleeping-Car Express” nv 1921 {The Premier Magazine}

12 Doyle, Arthur Conan “Silver Blaze” nv 1892 {The Strand}

12 Gores, Joe “Goodbye, Pops” ss 1969 {EQMM}

12 Jacobs, W. W. “Interruption” ss 1925 {The Strand}

12 Jacobs, W. W. “Monkey’s Paw” ss 1902 {Harper’s Monthly}

12 Quentin, Patrick “Puzzle for Poppy” ss 1946 {EQMM}

12 Rice, Craig “His Heart Could Break” nv 1943 {EQMM}

12 Sayers, Dorothy L. “Inspiration of Mr. Budd” ss 1926 {Pearson’s Magazine}

12 Vickers, Roy “Rubber Trumpet” ss 1934 {Pearson’s Magazine}

13 Dahl, Roald “Lamb to the Slaughter” ss 1953 {Harper’s}

13 Dickens, Charles “Hunted Down” nv 1859 {New York Ledger}

13 Doyle, Arthur Conan “Adventure of the Blue Carbuncle” ss 1892 {The Strand}

13 Forester, C. S. “Turn of the Tide” ss 1934 {The Story-Teller}

13 Knox, Ronald A. “Solved by Inspection” ss 1925

13 Patrick, Q. “Love Comes to Miss Lucy” ss 1947 {EQMM}

13 Stevenson, Robert Louis “Markheim” ss 1886 *The Broken Shaft: Unwin’s Christmas Annual*, ed. Sir Henry Norman, London: Fisher Unwin

13 Wynne, Anthony “Cyprian Bees” ss 1926 {Flynn’s Detective Fiction}

14 Bramah, Ernest “Tragedy at Brookbend Cottage” nv 1913 {News of the World}

14 Chesterton, G. K. “Hammer of God” ss 1910 {The Storyteller}

14 Collins, Wilkie “Terribly Strange Bed” ss 1852 {Household Words}

14 Doyle, Arthur Conan “Scandal in Bohemia” ss 1891 {The Strand}

14 Eustace, Robert & Jepson, Edgar “Tea-Leaf” nv 1925 {The Strand}

14 Glaspell, Susan Keating “Jury of Her Peers” nv 1917 {Every Week}

14 Huxley, Aldous “Gioconda Smile” nv 1921 {The English Review}

14 James, P. D. “Great-Aunt Allie’s Flypapers” nv 1969

14 Poe, Edgar Allan “Cask of Amontillado” ss 1846 {Godey’s Lady’s Book}

15 MacDonald, John D. “Homesick Buick” ss 1950 {EQMM}

15 Post, Melville Davisson “Doomdorf Mystery” ss 1914 {The Saturday Evening Post}

15 Queen, Ellery “Adventure of Abraham Lincoln’s Clue” [ “Abraham Lincoln’s Clue”] ss 1965 {MD}

15 Sayers, Dorothy L. “Adventurous Exploit of the Cave of Ali Baba” nv 1928 *Lord Peter Views the Body*, London: Gollancz

15 Sayers, Dorothy L. “Man Who Knew How” ss 1932 {Harper’s Bazaar}

16 Christie, Agatha “Accident” ss 1929 {The Daily Express}

16 Millar, Margaret “Couple Next Door” ss 1954 {EQMM}

16 Sayers, Dorothy L. “Suspicion” ss 1933 {Mystery League}

16 Wallace, Edgar “Treasure Hunt” ss 1924 {The Grand Magazine}

17 Barr, Robert “Absent-Minded Coterie” nv 1905 {The Saturday Evening Post}

17 Carr, John Dickson “Gentleman from Paris” nv 1950 {EQMM}

17 Kemelman, Harry “Nine Mile Walk” ss 1947 {EQMM}

18 Ellin, Stanley “Specialty of the House” nv 1948 {EQMM}

19 Chesterton, G. K. “Invisible Man” ss 1911 {Cassell’s}

19 Poe, Edgar Allan “Gold-Bug” nv 1843 {Philadelphia Dollar Newspaper}

20 Collins, Wilkie “Biter Bit” [ “Who Is the Thief?”] nv 1858 {Atlantic Monthly}

20 Dickens, Charles “To Be Taken with a Grain of Salt” [ “Trial for Murder”] ss 1865 {All the Year Round}

21 Gardner, Erle Stanley “Case of the Irate Witness” ss 1953 {Colliers}

21 Twain, Mark “Stolen White Elephant” nv 1882 *The Stolen White Elephant*, Webster

22 Doyle, Arthur Conan “Adventure of the Speckled Band” nv 1892 {The Strand}

22 Doyle, Arthur Conan “Red-Headed League” nv 1891 {The Strand}

22 Dunsany, Lord “Two Bottles of Relish” ss 1932 {Time & Tide}

25 Burke, Thomas “Hands of Mr. Ottermole” nv 1929 {The Story-Teller}

26 Berkeley, Anthony “Avenging Chance” ss 1929 {Pearson’s Magazine}

26 Poe, Edgar Allan “Murders in the Rue Morgue” nv 1841 {Graham’s Lady’s and Gentleman’s Magazine}

27 Futrelle, Jacques “Problem of Cell 13” nv 1905 {Boston American}

53 Poe, Edgar Allan “Purloined Letter” nv 1844 *The Gift: A Christmas and New Year’s Present for 1845*, 1844

Bill,

Thanks for generating those two lists.

Hats off to Ed Hoch for topping the list as most anthologised — but then as the most prolific still active writer of short stories, maybe he ought to be up the top there somewhere. Still, it shows his work is sufficiently memorable, though clearly no single story stands out as he’s not in the second list.

Conversely, Poe, Futrelle and Berkeley top the second list but don’t appear in the first. So we have a distinction here between writers who produce few major short stories but clearly a handful that hit the bullseye and those who produce many worthy stories but no individual one that stands out.

Once we get to Ellery Queen and Agatha Christie, though, they hit both lists and evidently these are writers who can produce both quantity and quality.

I think the first story that surprises me in the second list is Gardner’s “The Case of the Irate Witness”. It’s certainly not one that would have come instantly to mind and though I’m sure I’ve read it, I can’t bring it to mind at all! Intriguing to see Harry Kemelman’s “Nine Mile Walk” up there, too.

I previously put forward the argument that many of those that will top the list will be because their work is out of copyright, but though this may be a factor in why Poe and Futrelle top list 2, it certainly doesn’t apply to most of the stories and clearly not the authors in list 1. I’m rather glad about that. Quality shines through rather than being able to use a story on the cheap.

Mike A.

Sat 26 May 2007

ACEITUNA & JOY GRIFFIN – Motive for Murder

Sampson Low, Marston & Co; UK, hardcover. No date stated (but 1935, according to CFIV).

Neither lady was an author I’d heard of before I happened to read this book, and if you were tell me that you have a complete set of their combined works, I’m not sure I’d believe you. Joy Griffin has only the one co-authorship to her credit in Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin. Aceituna Griffin, on the other hand, has a few others, the first few of them of only marginal crime content, as indicated:

GRIFFIN, (Editha) ACEITUNA (1876-1949)

-Mrs. Vannock (n.) Nash 1907

-The Tavistocks (n.) Laurie 1908

-Pearl and Plain (n.) Longman[s] 1927

-Amber and Jade (n.) Longman[s] 1928

-Genesta (n.) Murray 1930

-Conscience (n.) Murray 1931

Delia’s Dilemma (n.) Pawling 1934

Motive for Murder [with Joy Griffin] (n.) Low 1935 [England]

Commandments Six and Eight (n.) Low 1936

The Punt Murder (n.) Low 1936 [England

Sweets and Sinners (n.) Low 1937

“Where There Is a Will…” (n.) Low 1939

By the judicious use of Google, I’ve found a few other non-crime books by her, romance and/or historical fiction by the looks of the titles. I won’t list them here, but the link is there to follow if you wish.

I did discover that Aceituna’s maiden name was Thurlow, which is something that Al Hubin hasn’t happened to have mentioned. Her husband’s name was Robert Chaloner Griffin, which throws my initial supposition that Joy and Aceituna were sisters right out the proverbial window.

Except for the book at hand, that’s as far as I’ve been able to go in digging up information about either of the authors. In regards to the book itself, I have to confess that I was hoping for more when I picked it up to read. Which of course is a comment you should immediately ignore, since a general rule of thumb for reviewers is to review the book you have, and not the book you thought you had.

Which is the story of Clarissa Lovell, a naive young girl nearing the age of 21 who was brought up by foster parents in a quiet, isolated section of England. When the two elderly folks who raised her decide to try their hand in Africa and become missionaries, Clarissa’s only option is to go live in London with her guardian and his wife, who are nearly strangers to her, and a change of scenery so abrupt from her previously sheltered life that her head spins at the thought of it.

What’s many times worse is that the new people who are now in charge of her life have Plans for her. The most immediate of these is that she marry their son, Gilbert, who seems only moderately interested in the idea himself. You may have noticed a phrase that I mentioned in the paragraph above — nearing the age of 21 — and I imagine that may give you an idea of what the Plans are all about.

Entangled in a web of deceit like this, as she slowly but surely finds out, she succeeds in making her escape, and only in the nick of time — matters having gotten rather tense right about then — and she heads off for Sicily on her own, where…

I’m sorry to say that I can’t say more, but please rest assured that things do not fare for her well there either, with Mrs. Maxton, her guardian’s wife, picking up her trail more quickly than sin.

You may also rely on my saying so that the unscrupulous plotters are really, really up to no good. Before Clarissa realizes it, she is once again in a rather bad spot. You may be surprised to learn that this rather naive approach to story-telling nevertheless makes for moderately enjoyable reading — if, and it’s a big if, you have the patience to give the book its head and allow it to find its own way, which it does very well indeed, thank you very much.

There is no detection in this book, though, a fact which is still greatly to my own personal regret, no matter what rule of thumb happens to be in force, just a good old-fashioned dose of gothic suspense taking place in another time and another place rather far from our own. Young girls could still be terribly unsophisticated in 1935, and maybe they were in the mid-1960s and 1970s when the gothic romance craze hit both England and the US again for reasons not yet totally clear, but other than that, not in recent times that I can think of, no.

Fri 25 May 2007

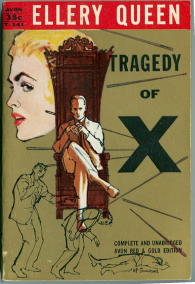

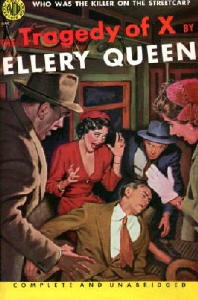

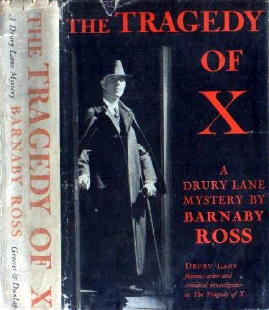

ELLERY QUEEN – Tragedy of X

Avon T-141; paperback reprint, no date stated, but generally accepted as 1956. Second Avon printing. Hardcover first edition as The Tragedy of X by BARNABY ROSS: The Viking Press, June 1932. Hardcover reprint: Grosset & Dunlap, mid-1930s. First hardcover edition as by ELLERY QUEEN: Stokes, 1940. (All editions that follow are all as by E.Q.) Hardcover reprints: Grosset & Dunlap, circa 1940 [or 1943]; University of California Extension, 1978 [Mystery Library, Volume 7; introduction & checklist by Francis M. Nevins, Jr.]; Bookthrift Co., 1986. Paperback reprints: Pocket 125, 1942; Avon 425, 1952; Avon S206, 1966; IPL, 1986.

Whew. And who knows, I may have missed an edition or two. In order to tell you more about the history and other insights about the book, I wish I had the Mystery Library edition, with the introduction by Mike Nevins. But I don’t, and I won’t try to fake it, but I will insert one short note I found on wikipedia.com: “For a while in the 1930s ‘Ellery Queen’ and ‘Barnaby Ross’ even staged a series of public debates in which one cousin impersonated Queen and the other impersonated Ross.”

What I’d be interested in knowing is how, when and who started to put two and two together and deduced the fact that Queen and Ross where one and the same. The four Barnaby Ross books came out in rapid succession during only a two-year period between 1932 and 1933, then there were no more. That the fourth one was titled Drury Lane’s Last Case made it as final and conclusive as possible there were only going to be four, even given the earlier resurrection of one Sherlock Holmes.

I believe I have read all four, but if I did, it was something like 50 years ago. When I came to read this one, now in my maturing years, I quickly discovered that it really didn’t matter if I really had read the book once before: I didn’t remember any of it, including (and especially) the ending, which tended (this time around) to knock my socks off. Whether it did or not before is a matter of only conjecture, but why else would I so vividly recall having read it, even without any accompanying details?

Drury Lane is the detective in all four mysteries, a retired (and deaf) Shakespearean actor with a penchant for helping the police in a purely amateur (but not amateurish) fashion, in particular and to whit, District Attorney Bruno and Inspector Thumm. On page 56 there is a reference to Lane’s giving them a hand on the “Cramer mess,” but since that case seems to have never been recorded, this would have been the reading audience’s first introduction to the man. (I picture John Carradine in the role, myself.)

Murder number one is that of a man poisoned to death on a trolley car. Means: a cork with needles dropped in the victim’s pocket. Circumstances: only one of the people on the trolley could have placed it there. More deaths follow, each one connected and each one as hopelessly complicated in commission as the first. Don’t expect anything like proper police procedure. The emphasis was on fooling the reader, in as extravagant a fashion as possible. For my money, the two men who were Queen succeed, and on all counts.

Well, let me quibble on that last statement perhaps a bit. That there are some awkward moments, designed not for realism, but caused by the authors’ reluctance to not reveal all too soon, as goes almost without saying. Drury Lane says more than once, for example, in true classic sleuthing style, that he knows who the killer is, but he can’t say who it is. Statements like this are always annoying, no matter which classic sleuth it is who says it. That it takes 36 pages for the solution to be revealed, step by step, will tell you something about what kind of book this is, as if you didn’t already know. In the explanation, though, Lane also reveals how he knew, and even more — and this is the clincher — why he couldn’t say who when he did.

This is also one of those kinds of mysteries which I do not believe are written any more, nor have they for a long time, in which the key to killer’s identity is not revealed until the last page.

Make that the last paragraph. The last sentence. And, keeping in mind the title: The. Very. Last. Letter.

X.

No, they don’t write books like this any more. Even given the quibbles I mentioned, wow, what a pleasure this was to read. (I did mention up above what happened to my socks, didn’t I?)

Next Page »