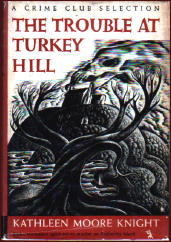

KATHLEEN MOORE KNIGHT – The Trouble at Turkey Hill.

Doubleday Crime Club, hardcover, 1946. Hardcover reprint: Detective Book Club [3-in-1 edition], June 1946.

My wife Judy and I moved to Connecticut in 1969. I’m a transplant from Michigan and not a native New Englander at all. I don’t know if there really is a Penberthy Island, where many of Kathleen Moore Knight’s books take place, and if there isn’t, while I can’t tell you which one she may have used as a model, Martha’s Vineyard certainly suggests itself.

No matter. There has to be plenty of communities all along the Cape Cod coast that are just like it, and all of them are ideal places to live, too, if you don’t mind tourists. I count a total of sixteen Elisha Macomber murder mysteries, he being her most commonly used series character. On a per capita basis, I think you’d have to admit, Penberthy would have to be a terribly dangerous place to hang your hat.

What Elisha Macomber does is operate the village fish market, but besides that, he’s also the chairman of the local Board of Selectmen. So in addition to being considered an autocratic father figure by the entire island, he’s also the investigative officer whenever another murder occurs.

In this case he’s in charge of tracking down the killer of the wife of a recently returned war veteran.

Telling the story is Miss Marcella Tracy, librarian and former school teacher. A lot of strange things happen to confuse matters, and even though everyone already has a sharp eye out into everyone else’s affairs, I got the feeling that calling all the suspects together into one big room to be confronted with all the evidence all at once might not have been such a bad idea. It’s that kind of story.

I’m too embarrassed to say that I mucked the solution up something fierce, so I won’t.

— Reprinted from The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 3, No. 4, July-Aug 1979 (revised).

[UPDATE] 02-28-09. One of the corrections I made in the review was the number of Elisha Macomber books there were. The number above is now the right one. Kathleen Moore Knight also wrote four books between 1940 and 1944 with Margot Blair as the leading character. According to the Golden Age of Detection Wiki, Blair was a partner in a public relations firm called Norman and Blair.

I don’t think I’ve read any of the latter’s adventures, but I have read (and as I recall, enjoyed) three or four of Elisha Macombers, which appeared over a long period of time, from 1935 to 1959. That’s a long run for a fellow who’s probably next to unknown to most mystery readers today. It is a shame.

From the Revised Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin, here’s a list of all sixteen. Note that a couple of pre-war cases took place in Panama. Macomber then disappeared for six years while the war was going on. I wonder what that was all about.

MACOMBER, ELISHA [Kathleen Moore Knight]

Death Blew Out the Match (n.) Doubleday 1935 [Massachusetts]

The Clue of the Poor Man’s Shilling (n.) Doubleday 1936 [Massachusetts]

The Wheel That Turned (n.) Doubleday 1936 [Massachusetts]

Seven Were Veiled (n.) Doubleday 1937 [Massachusetts]

Acts of Black Night (n.) Doubleday 1938 [Massachusetts]

The Tainted Token (n.) Doubleday 1938 [Panama]

Death Came Dancing (n.) Doubleday 1940 [Panama]

The Trouble at Turkey Hill (n.) Doubleday 1946 [Martha’s Vineyard]

Footbridge to Death (n.) Doubleday 1947 [Martha’s Vineyard]

Bait for Murder (n.) Doubleday 1948 [Martha’s Vineyard]

The Bass Derby Murder (n.) Doubleday 1949 [Martha�s Vineyard]

Death Goes to a Reunion (n.) Doubleday 1952 [Massachusetts]

Valse Macabre (n.) Doubleday 1952 [Martha’s Vineyard]

Akin to Murder (n.) Doubleday 1953 [Massachusetts]

Three of Diamonds (n.) Doubleday 1953 [Martha’s Vineyard]

Beauty Is a Beast (n.) Doubleday 1959 [Martha’s Vineyard]

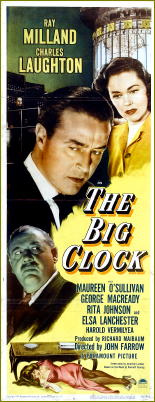

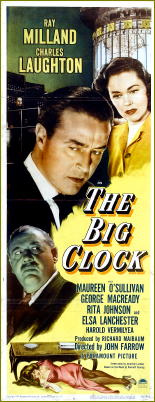

THE BIG CLOCK. Paramount, 1948. Ray Milland, Charles Laughton, Maureen O’Sullivan, George Macready, Rita Johnson, Elsa Lanchester, Harry Morgan, with uncredited appearances by Noel Neill and Ruth Roman. Screenplay: Jonathan Latimer, based on the novel by Kenneth Fearing. Director: John Farrow.

THE BIG CLOCK. Paramount, 1948. Ray Milland, Charles Laughton, Maureen O’Sullivan, George Macready, Rita Johnson, Elsa Lanchester, Harry Morgan, with uncredited appearances by Noel Neill and Ruth Roman. Screenplay: Jonathan Latimer, based on the novel by Kenneth Fearing. Director: John Farrow.

I’ve not read the book, or at least not so recently that I remember reading it, but from what I have been able to tell, the movie follows the text fairly closely — except for one thing. In the movie George Stroud, the highly successful editor of a true crime magazine, does not go to bed with the woman whose murder he finds himself framed for.

Otherwise the story apparently stays very much the same. The big kicker in both the book and the movie is that Stroud is put in charge of the ensuing investigation; that is, of finding the “killer,” himself, by his publisher, Earl Janoth, who in actuality — and in a sudden burst of abhorrence — really did commit the murder. The dead woman was Janoth’s mistress, and their relationship had been going sour for several weeks.

If I’m wrong about the book, let me know, but Jonathan Latimer’s screenplay can stand on its own, regardless. Ray Milland plays George Stroud, a very capable, self-assured fellow, but a very foolish guy in hanging around with Pauline York (Rita Johnson) when he has a wife (Maureen O’Sullivan) who is still waiting for a honeymoon after seven years of marriage.

Milland is very good as the man who finds himself more and more trapped in a web partly of his own making, as his own team of reporters continues to close in on him at Jaroth’s command.

Even better is Charles Laughton as that very same fastidious publisher, prig and interminably stuffy, a haughty person obsessed with time and efficiency and minimal cost, only to startle himself (momentarily) into becoming a normal person afraid of being caught at something he later can’t comprehend having done.

Maureen O’Sullivan doesn’t have a lot to do as Georgette Stroud, only to nag him (and rightfully so) and then stand beside him (at last) when he needs her most. Most viewers call this a classic noir film, and even if you haven’t seen it yourself, I hope my description of it will have you nodding your head and saying yes.

Occasionally disrupting the dark and desperate mood, though, are a few moments of comic relief, mostly (but not solely) at the hands of Elsa Lancester as a wacky, bohemian artist with a flat full of kids who can identify Stroud, but for (very good) reasons of her own, decides not to.

I certainly didn’t mind the comic interludes, but I wonder if purist noir aficionados do. The ending is a doubly happy one (I think), preceded by some very good detective work. Most entertaining, with emphasis on the “most.”

I watched this movie about several weeks ago, and I just watched it again before writing up these comments. I enjoyed it immensely both times, but there is a lot going on in this movie that I haven’t even begun to mention, and it takes more than one watching to appreciate it all.

I have it penciled in on my calendar to see it again in about a month from now.

PostScript: Ray Milland, Jonathan Latimer and director John Farrow teamed up at least one other time in Alias Nick Beal (1949), which I reviewed here last summer.

FRANK RAWLINGS – The Lisping Man.

Atlas Mystery/Hercules Publishing Corp.; digest-sized paperback; first printing, 1944; abridged. Hardcover edition: Gateway Books, 1942. Based on the short novel “Calling the Ghost,” the first appearance of the Ghost/Green Ghost pulp hero character, magician-sleuth George Chance, in The Ghost, Super-Detective, January 1940, as by G. T. Fleming-Roberts.

For a longer and much more comprehensive look at the complicated background behind this story, go to Monte Herridge’s excellent article “Chance Without a Ghost,” located here. Monte goes into a considerable amount of detail in pointing out all of the changes that were made by Fleming-Roberts between the pulp story and the digest paperback, with a hardcover appearance in between.

The most significant of these alterations turned out to have been all of the pulp hero apparatus that was abandoned for the novel — no secret identity nor hidden hideaway nor so on — leaving George Chance as only a magician by profession and a crime-solving sleuth as a sideline, only one step up from being a hobby, you might say.

Monte did not believe that the story was very good.

I agree. In fact, I thought it was quite bad, if not awful, but with reservations. Working pretty much in the dark, I’m inclined to lay a good chunk of the blame on the second set of changes: on whoever the editorial staff was whose responsibility it was for trimming a standard-sized hardcover down to a fairly slim paperback. The latter is the only version I have, and as it was for Monte, that’s all that I can base my comments on.

So how much was cut, or whether it was done crudely or with any amount of skill, I do not know. The fact is that when a book is cut and trimmed and comes out as, well, ineptly as this one, it’s difficult to give the full responsibility to the author for how the final version reads, especially as in this case, when it does not turn out well.

[FOLLOWUP: It’s not exactly a footnote, but Bill Pronzini, a fellow pulp fiction aficionado, will have more to say about this when I’m finished with the rest of the review, which follows. Keep reading.]

I mentioned that crime-solving was an avocational passion for George Chance. A good example that I can use to demonstrate just exactly how obsessive and attracted Chance is to strange murder cases comes only one or two chapters into the book, as he leaves his new wife Merry on their wedding night to help Inspector Ames investigate the suicide of one Leonard Van Sickle, who apparently jumped (or was pushed) from a hotel room twenty floors above the pavement.

What makes this a strange case is that Leonard Van Sickle had telephoned Chance only hours before, with no indication in the call that he was planning on ending his life. What is also strange is that he talked with a lisp. Hence the title. It also turns out (page 67) that the dead man had recently had all of his teeth extracted.

Explains the dentist:

“I wouldn’t have complied with the patient’s request to extract healthy teeth had it not been for the fact that I needed money badly,” Dr. Chambers confided. “I thought there was something suspicious about the whole setup. …”

As you have probably suspected, there is something funny about it, all right, and you also would probably not be astonished to learn that there is a lot of fuss made about life insurance policies and who collects and who doesn’t.

There is some intelligence behind the plot, but it is seemingly indifferently and/or non-skillfully told most of the way through, culminating in a “gather all of the suspects together” scene that does not depend on more than a modicum of a magician’s sleight-of-hand in any substantial manner, shape or form.

What it does rely even more upon is the answer to the question, “Whose hands will show up like phosphorus under an ultra-violet light?”

It didn’t take a magician to think of this. I think that if a magician is a sleuth, he ought to do more with his prestidigitation and legerdemain than pull cigarettes out of the air or coins out of people’s ears. (I’m speaking figuratively here, as what is up George Chance’s sleeve at a crucial moment is, well, crucial.)

There is a decent detective novel hidden in the depths of this one, perhaps. I just didn’t happen to read it, or I was too lazily intent at the time on reading the one that was there, not the one it could have been.

FOLLOWUP: After finishing my review above, and telling Bill Pronzini only the gist of what I’d said, I asked him about the differences between the hardcover and the paperback version of the novel. (I could think of no one else who might possibly have read both.) Here’s his reply:

“The uncut hardcover edition of

The Limping Man is marginally better than the abridged paper one, which eliminates a fair amount of descriptive material that fleshes out the story and some connective material whose absence makes for choppy reading. It’s still not a very good novel, though, particularly when compared to the pulp version — no doubt the reason Fleming-Roberts didn’t want his own name on it and why it didn’t find a better publisher than Leo Margulies’ Gateway.”

Thu 26 Feb 2009

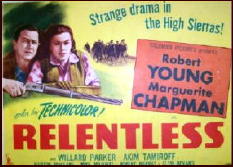

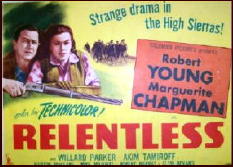

RELENTLESS. Columbia, 1948. Robert Young, Marguerite Chapman, Willard Parker, Akim Tamiroff, Barton MacLane, Mike Mazurki, Clem Bevans. Based on the novel Three Were Thoroughbreds by Kenneth Perkins. Director: George Sherman.

RELENTLESS. Columbia, 1948. Robert Young, Marguerite Chapman, Willard Parker, Akim Tamiroff, Barton MacLane, Mike Mazurki, Clem Bevans. Based on the novel Three Were Thoroughbreds by Kenneth Perkins. Director: George Sherman.

I taped this movie many years ago, but for a time that was just as long, I put off actually sitting down and watching until several days ago. I just couldn’t see Robert Young as a cowboy star, you see. Once you know an actor as a family man (Father Knows Best) or a kindly family doctor (Marcus Welby, M.D.). it’s hard to go back and see him in a western like this one, or even a crime film. He just doesn’t fit the image.

Looking through his list of credits, though, I see that Young was in Western Union (1941) and another film I don’t recall knowing about before, The Half-Breed (1952). I may have missed another, but even so, while it’s not a long list, he’s hardly a zero in the western category. (His first movie credit may have been The Black Camel, the 1931 Charlie Chan film with Warner Oland.)

And in Relentless he proved to me that he could shoot, he could ride, and he was good with horses, and that’s a fact, even if he still looks like a dude to me. In the story, he’s a drifter who’s framed for the murder of one of a pair of claim-jumpers.

Turns out, of course, that it was the other half of the pair who did it, and to clear his name Nick Buckley (that’s Young) has to track down the real killer (that’s Barton MacLane) while the sheriff (Willard Parker — he’s the one on the right in the lobby card above — who later became Ranger Jace Pearson on TV’s Tales of the Texas Rangers) is hard on his heels throughout the movie.

Where does Marguerite Chapman come in? you ask, and you should. She’s the proprietor and sole operator of a general store in a covered wagon, sort of a traveling saleslady, you might say. When she (Luella Purdy) and Nate Buckley both proclaim their independence and total disinterest in getting hitched up with anyone, you know from that moment on that their fate is sealed — even though when Luella once shows up in a dress rather than in her rather fetching cowgirl garb, Buckley barely takes notice — seemingly far more interested in the colt he’d had hopes of raising into a race horse than in her.

Marguerite Chapman, a vivacious brunette and a true girl-next-door type, had a decent career in Hollywood, but sadly, I don’t believe that the general public remembers her at all today.

Interestingly, IMDB says she was asked to appear as “Old Rose” Calver in Titanic, but she was too ill at the time (1997, when she was 89) and the role went to Gloria Stuart. (She’s far too glamorous in the close-up photo I’ve found. She doesn’t look anything like this in this movie, but I thought I’d show it to you anyway.)

As for the movie itself, filmed in color to good effect, it keeps the players on the move throughout the film, with more than enough story line to fill its full 90 minutes or so. It’s even entertaining enough to watch a second time.

But getting back to Robert Young, even after all this, I still have to tell you that he’s too soft-spoken and nice to be a western star. As a guy more interested in his horses rather than the girl — for all but the final scene! — he’s dumb enough in that sense to be one, that’s for sure.

Wed 25 Feb 2009

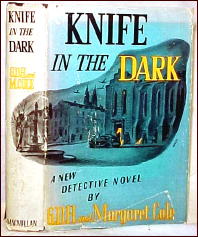

G. D. H. & MARGARET COLE – Knife in the Dark.

Collins Crime Club, UK, hardcover; Dec 1941. The Macmillan Co., US, hardcover, 1942 (shown).

More than usual, there are a couple of remarkable aspects to this wartime mystery. The first is the identity of the primary sleuth, and it is definitely not private detective James Warrender, as I carelessly (and rather chauvinistically) assumed when I picked the book up to read. Unh-uh. Not at all. It’s Mrs. Elizabeth Warrender instead. His mother.

Belatedly checking with Hubin’s Crime Fiction IV, I found that this was the only full length novel in which Mrs. Warrender was in. Altogether the Coles wrote more than thirty mysteries, and the detective in most of them was Scotland Yard’s Superintendent Wilson. While James Warrender’s mother appeared in an earlier collection of novelettes and short stories called Mrs. Warrender’s Profession, 1939, this was the only novel.

Someone else will have to tell me, because I can’t come up with any — what other private eye character ever found himself upstaged in a detective story by his mother?

The other aspect that I found remarkable — and so, therefore, I’m obliged to remark on it, aren’t I? — was the identity of the murder victim. Up until her death, I thought she had the most vibrant, most interesting personality of anyone else in the book, and it was difficult to see her go.

Not that she was without faults. Check the date of the novel again. As the wife of a dull academic in a university town, the woman was well known for her intolerance and for speaking out against the aliens being resettled in the city — refugees from a Europe suffering from a war we here in which the United States had not yet become involved. The lady was also a bright flame in the town’s small community of scholars, drawing unattached students to her like the proverbial moths, not to mention the occasional faculty member.

She, in fact, is at one point described in a word I doubt that Agatha Christie ever used, a nymphomaniac. (Erle Stanley Gardner might have called this book The Case of the Unscrupulous Siren.)

The murder takes place at a public dance for which she was the hostess, and there are many suspects, many opportunities, a coincidence or two, and — it’s just the kind of mystery the Golden Age of Detective Stories is known for, even if the details of the plot aren’t quite as sharp as they should be. (Fuzzy around the fringes, you might say.)

Mrs. Warrender, approaching 70 in this book, is perhaps of a little higher class standing than the aforementioned Mrs Christie’s Miss Marple, but she has the right instincts, and I humbly apologize to her for wondering why on earth the private eye’s mother is tagging along with him.

— February 2003

[UPDATE] 02-25-09. Quite remarkably, when I fished this review of out of the “archives,” the only two things that I remembered about the book were the two things that I wrote about it in my commentary. Either I was spot on in writing it up the first time, or in the process of writing it up, it reinforced in my mind the two aspects of it that I would find again remarkable at a later date; that is to say, now.

Mon 23 Feb 2009

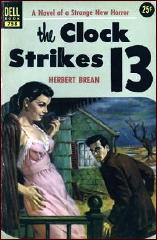

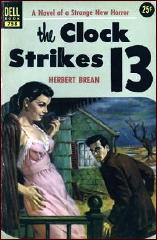

HERBERT BREAN – The Clock Strikes Thirteen.

William Morrow, hardcover, 1952. Paperback reprint: Dell 758, [1954]. A shorter version first appeared in Cosmopolitan magazine, June 1952.

I’ll tell you this, I’ve never read a mystery quite like this one. It takes place on a desolate island, off the coast of Maine. There’s no animal life and no vegetation. It’s completely dead and abandoned, all except for a small group of dedicated research biologists, busily working away on more, even more deadly concoctions for the Defense Department.

But soon after journalist-photographer Reynold Frame arrives, summoned by a soon-to-be announced discovery, the scientist in charge (not quite mad) is clubbed to death, and several trays of germ culture are overturned. With all contact with the mainland cut off, and with the threat of sudden death constantly in the air, the murder investigation perforce goes on.

In spite of the bizarre, even grotesque setting, Frame does a more than passable job of detection. However, after recently reading any number of newspaper articles of sheep, nerve gas and the like; and considering what we know now about how easily science can be used to kill effectively and indiscriminately, reading Brean today, he’s not half as frightening as he could have been.

I’m sure he used all the information about bacteriological warfare that he was allowed access to, but looking back, I think that 25 years ago we were all probably quite naive.

PostScript: This was the last of the four mystery novels that Reynold Frame appeared in. He seems to have walked from the rescue boat onto the Maine shoreline, and into oblivion.

— Reprinted from The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 3, No. 4, July-Aug 1979 (slightly revised).

[UPDATE] 02-23-09. I can’t remember reading this book at all, so I can’t expand on what I said back then. Nor do I know very much about Herbert Brean, I’m sorry to say, only the list of seven titles that are listed under his name in the Revised Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin.

He was well enough regarded as a mystery writer, though, using Google as a guide, that at one time “he was a director and executive vice president of the Mystery Writers of America, a group for which he also taught a class in mystery writing.” (Wikipedia)

A series detective named William Deacon (described in several places as a “crack magazine writer”) appears in his last two mysteries, both published in the 1960s. But taken from CFIV, here’s the list of all four in which Reynold Frame did the detecting.

FRAME, REYNOLD [Herbert Brean]

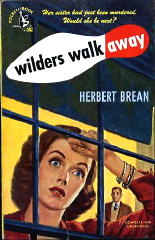

Wilders Walk Away (n.) Morrow 1948. [An impossible crime mystery.]

The Darker the Night (n.) Morrow 1949.

Hardly a Man Is Now Alive (n.) Morrow 1950.

The Clock Strikes Thirteen (n.) Morrow 1952.

Sun 22 Feb 2009

No self-respecting mystery-oriented blog, especially one that also covers crime films, should be in existence very long without a discussion of Noir and “What’s a Noir Film?” breaking out.

It’s been touched on now and again here on Mystery*File, but while you may not have noticed, a lengthy conversation recently took place here, one that covered the subject more intensely than has ever happened before.

And, of all place, in the comments section of an old review I posted of Phantom Valley, a Durango Kid movie released by Columbia in 1948.

Here’s the last paragraph, in which I said of the leading lady:

“Virginia Hunter is very pretty and attractive, but she seems to have had only a short career in films. Her roles include at least one other Durango movie, several Three Stooges shorts, and a small part in the noir thriller He Walked by Night (1948). Mostly B-movies, looking down through the rest of the list, and often small uncredited parts at that, but she makes the most of this one.”

Since some interesting things were said, I’ll let those who commented take over from here:

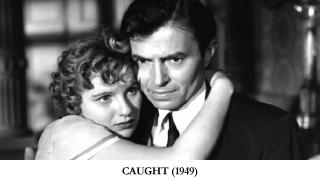

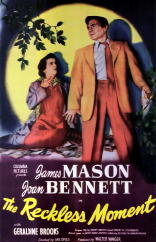

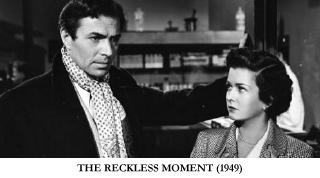

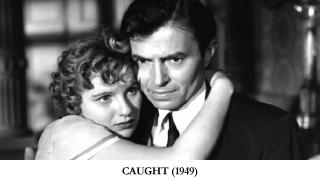

MIKE GROST: “The IMDB says Virginia Hunter has tiny roles in Caught and The Reckless Moment, two films in the genre variously known as melodrama / romantic drama / Women’s films / soap opera. Both were directed by Max Ophuls. Ophuls is one of the most admired directors today, and his works are considered major classics. There are many books on him, including Max Ophuls in the Hollywood Studios (1996) by Lutz Bacher.

“I don’t remember Virginia Hunter in Caught at all. She must have had a very small part.”

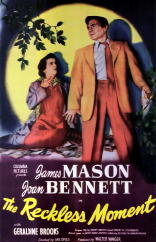

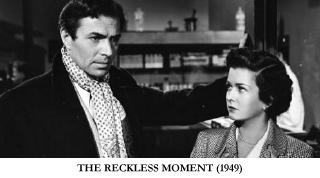

WALKER MARTIN: “Mike, concerning Caught and The Reckless Moment, I agree with your use of the word ‘melodrama’ but I’m not so sure about the words ‘romantic drama/ Women’s films/soap opera.’ I viewed both these films about a year ago during my present habit of watching a film noir movie just about every night on dvd (these two films are on British PAL discs). They are definitely film noir with Caught starring James Mason and Robert Ryan and The Reckless Moment starring James Mason and Joan Bennett.

“Both films are listed in such basic film noir references as Film Noir: An Encyclopedic Reference by Alain Silver and Elizabeth Ward and Film Noir Guide by Keaney. You are right about Max Ophuls being one of the great directors but I guess we have to agree to disagree about these movies being women’s films or soap opera.”

DAVID VINEYARD: “The Reckless Moment is based on a novel by Elizabeth Saxnay Holding, The Blank Wall (1947). The Brooklyn-born Holding was married to an Englishman, and author of several well received novels pioneering the field of psychological suspense. The film is clearly in the noir mode with iconic noir actress Joan Bennett in the lead as a woman being blackmailed by James Mason. Anthony Boucher and Raymond Chandler were both champions of Holding’s work with Boucher crediting her with virtually creating the modern novel of psychological suspense.

“Caught, while also clearly in the noir mode, is also clearly a modern gothic in it’s plot of a young woman (Barbara Bel Geddes) who discovers her husband (Robert Ryan) isn’t who she thought he was and falls for the doctor(James Mason) who suspects foul play, but her escape is complicated because she is pregnant by her husband. It’s based on the novel Wild Calender by Libbie Block.

“Both films are generally listed in most noir reference books, though they might fit in a sub-category from the usual crime, spy, and private eye fare we tend to think of as noir. Other films in this more romantic noir mood include Fallen Angel, Leave Her to Heaven, Angel Face, and No Man of Her Own (based on Cornell Woolrich’s I Married a Dead Man).

“Though they are both pre-noir (officially noir begins with 1946’s Murder My Sweet, though plenty of films before that have noirish elements)these more romantic and femme centered noirs were often a mix of elements from Rebecca and Mildred Pierce, though they often featured iconic noir actresses such as Bennett, Bel Geddes, and Barbara Stanwyck.

“And before everyone piles on to mention the countless films that came out before 1946 that clearly have noir elements, the date is not entirely arbitrary. The term was coined by the French and was not used or recognized as a specific genre before that date. I can think of any number of films before Murder My Sweet I would call noir too, but film historians point out that noir couldn’t technically exist until the term was coined, however many films we think of as noir may seem to fit the pattern.

“I lean to including the pre-noirs in the general accepted genre, but don’t stretch quite as far as some so called noir collections on DVD that frankly seem to be pushing the boundaries to any film that deals with a crime and makes use of shadows in their cinematography.

“A perfectly good example would be Scotland Yard Inspector with Cesar Romero, which is available in one of the Film Noir sets. The film is an entertaining British B mystery in the Peter Cheyney mode, but it isn’t noir by any means.

“Noir is more attitude than subject matter, and as the old line goes, you know it when you see it. Some of these definitions would include any film that was in black and white and wasn’t a comedy, musical, or western.”

WALKER MARTIN: “Yes, we can argue all day about what is film noir and what period constitutes the film noir years, etc. I often see critics saying 1941-1959 is the basic film noir era. However, I have seen movies prior to 1941 that I would call film noir and I’ve seen alot of movies after 1959 that are certainly film noir or neo-noir. To try and pin down the exact definition or period will drive us crazy.

“For instance one of my favorite reference books is Film Noir: An Encyclopedic Reference by Silver and Ward. Since 1979, I have been checking off the films as I view them, listing the date viewed and my grade concerning quality. Sometimes I scribble a comment such as ‘This is not film noir.’

“A couple nights ago was the most recent time that I wrote this comment. I finally found a poor print of Thunderbolt, a 1929 early sound movie starring George Bancroft and Fay Wray. Despite Silver and Ward listing it in the book, there is no evidence that this film is anything more than a crime/prison drama. Yet they see some type of pre-noir element that justifies inclusion in the encyclopedia.

“I’m pretty liberal in what I include as film noir and I have to be, otherwise I would drive myself mad. The main thing is I enjoy this type of movie.”

MIKE GROST: “I’ve never seen The Reckless Moment. It’s good news that it is at last out on DVD!

“It’s certainly true that Caught is widely viewed as a noir. But I’ve always been a bit skeptical. Films like Fallen Angel or Mildred Pierce have murder mysteries in them. Everyone agrees they are noir.

“But there is no crime or even violence in Caught. It’s about a woman and her romantic affairs.

“Caught does have some character types we associate with noir. Robert Ryan’s nasty millionaire shows the ‘alienation and obsession’ Alain Silver rightly associates with noir. And the film is often dark in mood.

Still, I think ‘noir’ is best restricted to films with actual crime elements. Maybe we can all agree that Caught is ‘noir-like’…

“I last saw Thunderbolt (Josef von Sternberg, 1929) in 1972. Thought then it was a masterpiece! This is another film that badly needs to get back in circulation. Sternberg was a giant of the cinema.

“Have no opinions about whether is is pre-noir. Was astonished back then by its rich use of sound. It seems like one of the most creative and emotionally laden of the early talkies.

“Hardly anyone in Hollywood used the term noir, even after the French coined it circa 1946. Silver and Ursini’s Film Noir Reader 2 presents strong evidence that Hollywood called such films ‘crime movies,’ and thought of them as a distinct genre. IMHO ‘film noir’ is a great catchy name for this genre, and better than simple ‘crime movies.’ But the genre pre-existed its name. Films like The Stranger on the Third Floor and This Gun for Hire, made long before 1946, sure seem like film noir to me.”

DAVID VINEYARD: “I agree about stretching the limits of noir to include films made before and after the general cut off points. Certainly some of the pre code films have noir elements, as do films like Lang’s You Only Live Once and Fury (though I think in all honestly both are really crime drama and social drama respectively).

“Even strict constructionists who insist on the 1946 date will admit (reluctantly) that if The Big Sleep had been released in 1945 before Murder My Sweet instead of delayed a year (the 1945 cut has been restored) it would be the first true noir, but then the French invented the term to refer to a type of film that clearly goes back at least to the thirties and which they imitated in films like Jour le Seve and La Bete Humane (which Lang remade as a noir with Glenn Ford, Gloria Grahame, and Broderick Crawford).

Anthony Mann’s westerns since under that definition a western couldn’t be noir, though there are certainly noirish elements in many of them (and directed by notable noir directors).

“And in relation to the article, if it’s based on Cornell Woolrich isn’t it film noir by definition? The Falcon Takes Over and Time to Kill from the Michael Shayne series based on Raymond Chandler’s Farewell My Lovely and The High Window both have noir elements just by the nature of the stories, but though they are superior B series entries I don’t think either one is really noir. What is and isn’t noir is likely to be argued for a long time.

“I would likely agree to limiting noir to crime films, though in the case of Caught the combination of the actors involved — especially Robert Ryan — the look of the film, and director Max Ophuls there is certainly a case to be made for calling it noir.

“Even within the strictest definition of the genre there are films as diverse as the nihilistic Detour, the docudrama style of He Walked By Night or Lineup, and the moody romance of Out of the Past that are noir icons, but have little in common other than crime and being filmed in black and white. I suspect in the case of noir the answer lies in the eye of the beholder within some general guidelines.”

LUTZ BACHER: “In Caught, Virginia Hunter plays ‘Lushola,’ the inebriated woman who keeps interrupting Lee and Quinada at the bar in the Nightclub scene. In Reckless Moment, she’s seen more briefly at the juke box in the hotel bar (the second bar scene, near the end), repeatedly saying ‘same song again.’”

Me, Steve, again. Thanks to all who commented, with a special tip of the cap to Lutz Bacher for the definitive answer to who Virginia Hunter played, and when, the question which began this entire conversation!

Sat 21 Feb 2009

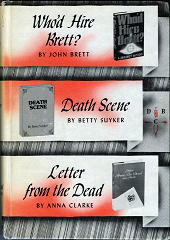

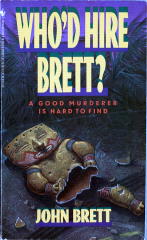

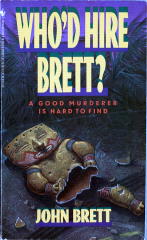

JOHN BRETT – Who’d Hire Brett? Detective Book Club [3-in-1 edition]; hardcover reprint,. Sept-Oct 1981. First edition: St. Martin’s Press, 1981. Paperback reprint: Bantam, July 1989. No UK edition.

My copy is the DBC edition, one of the so-called “Inner Circle” volumes in that set of books, and the only one that I could find a cover for — although I suspect I have the Bantam paperback, somewhere.

There’s not much information about John Brett, the author. This was his only detective novel, and in the Revised Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin, he’s described only as “born in England, the son of an earl; living near Hollywood,” a statement possibly obtained from the blurb on the hardcover edition. Now since this describes the character John Brett, except for the “earl” part, awfully well, I have a feeling that “John Brett” is not the author’s real name.

And since he’s relatively skilled as an author, it’s also possible that we might know him as a mystery writer under another name altogether. Not that I have any suggestions.

Getting back to the “earl” part, that might be true for the character in the book, too. He’s a glib sort of fellow who tells the story himself, but in doing so, he only hints at his background. He, we soon gather, is what’s called a remittance man — an exile living on money sent from home — in this case England. Something shady and quite possibly illegal back went on back there, but as I say, hints are all he’s going to give.

He’s not exactly hired in this book, in spite of the title, but he is asked by a female friend to steal a valuable artifact from his upstairs neighbor, the upstairs neighbor having stolen the artifact from the female friend and her husband, they having it in their possession illegally, which is why they can’t call the police in on the theft.

With me so far? I’ll let Brett take over to tell you what happens next. He’s just turned the icon (a Mud Dancer) over to the husband, Harry:

“As I watched him drive off, I thought, considering it’s a quarter of five in the morning, and a theft has just been committed, and a secret rendezvous, and all that, wouldn’t it be interesting if a big black sedan, maybe a Buick or a Cadillac, or even a Rolls, were to pull up and someone were to pump old Harry full of holes?

“Which is precisely what happened, at precisely that moment.”

The police, naturally, suspect Harry’s wife, and since John Brett is close friends with the wife, they suspect him, too, for a while. To clear their names in the eyes of Sgt. Steinberg — apparently the only cop in the Beverly Hills Police Department, for he’s the only one who ever appears in person anywhere in the book — John and Edie and Edie’s enterprising and eavesdropping maid Marie decide to do a little sleuthing on their own. Make that a lot of sleuthing, although John has to be prodded by Marie, who’s another story, and being John’s age (Edie is older), sparks begin to fly, and more.

I’ve been doing some hinting myself, but right now I’ll come out and say it. This is a comic caper in the same sense as many of Donald Westlake’s books under his own name were comic capers, not that I’m saying that Donald Westlake was the author of this book, though it’s kind of fun to imagine that he was.

From page 60, just to give you a good idea. John and Marie are on the case together:

“I pointed the Sunbeam in a direction that seemed likely to get us somewhere near the Beverly Hills Police Department. It didn’t. Instead, we wound up in a rather dismal place called Culver City that has a lot of strange-looking streets meeting at even stranger intersections. In Culver City, I discovered; nothing goes anywhere. Everything is coming from somewhere and seems to dissipate into nothingness. It’s what astronomers are lately calling, with a remarkable lack of cheeriness, a Black Hole. Everything collapses into it, and damned little gets out again. I began to flounder, and I’m afraid that the sight of a half-crocked Englishman floundering in a Sunbeam with a rather dazzling redhead at his side was enough to make the day for the locals. Not that they lined the streets to cheer, mind you, but I noticed a certain mocking quality in the eye of the policeman who stopped us.

“‘Going somewhere?’ he asked.

“It struck me as a rather stupid question, as it must have been obvious to him that we were not. After all, he had just succeeded in following us in five complete circles.

“‘Beverly Hills Police Department?’ said I, giving him the bright smile.

“‘Wrong town. Try again.’

“Well, I knew it was the wrong town, for God’s sake. All I was trying to do was get it across to him that directions were needed. He was obviously dense. I tried again.

“‘We want to go to the Beverly Hills Police Department.’ I tried to wither him with a look this time. Take my word for it: don’t ever try to wither a Culver City cop. They take it personally.”

To get back to the case, however, this really is a detective story, although with all of the wackiness going on, you might begin to wonder. There is one line in the book which John Brett, for all of his semi-doltishness, which is obviously a front, picks up on and knows (he says later) who the killer is, right then and there. He’s right. If you read it correctly, you will, too.

What I don’t know is whether or not his knowing then fits in with the rest of the book, as he tells it. That is to say, if he (or you or I) knew then what he says he knew — well, I’d have to read the book again.

While in a one sense it’s completely out of character, it could very well be that John Brett is an even deeper character than he otherwise ever lets on.

Since this was his only recorded outing as a detective, we may never know.

[UPDATE] 04-23-09. As you see, I have found my copy of the Bantam edition.

Fri 20 Feb 2009

“There’s an old story about the person who wished his computer were as easy to use as his telephone. That wish has come true, since I no longer know how to use my telephone.” (Bjarne Stroustrup)

I spent a good deal of yesterday and most of this morning trying to read my email. I probably shouldn’t still be using Eudora, but I’m comfortable with it. Yesterday it was a bad certificate, whatever that it is. Cox.net, of course, had no idea, but after I finally spoke to a sympathetic tech support fellow for a lengthy time — though he claimed the problem was not at all at their end — five minutes after I hung up, the problem quietly disappeared.

This morning I couldn’t log in. Needed a password. First time in six years. Was there a way to find out what it was? No. To change it? No. The online east cox mail server was down, at least for me — was yesterday, too — and the west server really didn’t want to know me either. A little finesse, which took a couple of hours, did the trick. I’d done something I really shouldn’t have the day before, but who knew? The two passwords match now, and I wrote it down someplace safe, believe you me.

Thanks to my daughter Sarah and her husband Mark for keeping me cool. Otherwise the computer would have been out the window, as per Steve Wozniak.

What a waste of time.

But me, bitter? Nah. Not a chance in the world.

“It has been said that the great scientific disciplines are examples of giants standing on the shoulders of other giants. It has also been said that the software industry is an example of midgets standing on the toes of other midgets.” (Alan Cooper)

Wed 18 Feb 2009

Posted by Steve under

ReviewsNo Comments

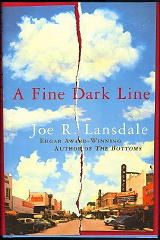

JOE R. LANSDALE – A Fine Dark Line.

Mysterious Press, hardcover; January 2003; trade paperback: October 2003.

On page 7, when thirteen-year-old Stanley Mitchel learns that there is no Santa Claus, he doesn’t like it. He feels “like a big donkey’s ass.” He doesn’t know it, but his small comfortable corner of the world is starting to crumble. Nor does he know what else is in store for him during that summer of 1958, but in the hands of Edgar-winning author Joe Lansdale, it’s pure magic, at least to the reader, and this one in particular.

What happens to Stanley and his family in this one brief summer is more than what occurs to most people in twice their lifetime. Finding a metal box filled with letters and pages from a diary buried in the ground, seems to trigger a seismographic sequence of events that takes the East Texas town of Dewmont across some unknown and never before seen line separating dark mystery from reality.

The boom-times spawned by the end of World War II took their time reaching rural America, forcing Stanley’s father to uproot the family and head to the big city, where they make their new home inside the huge screen of the drive-in theater that’s the source of his new livelihood.

The year 1958 was an innocent age of Dairy Queen’s and rock-and-roll, back when the black population knew their place, and the white population kept them there, not always maliciously, but simply because that’s the way it was and always would be. And yet aiding young Stanley with his investigation of the letters, and the two young girls who died (were murdered?) on the same night some 25 years before, is Buster, his father’s aged black projectionist — and Stanley’s ad hoc mentor leading him on this passage to adulthood.

It’s an education, all right. Lynching of black men had ended not very much earlier, and minstrel shows were still common, but in 1958, to Stanley and his family, the entertainment value seems to diminish before their eyes. Stanley’s sixteen-year-old sister is growing up as well, and her explanation of certain aspects of life begins to open brand new horizons for him.

It’s a remarkable trip, told by a master of words and nostalgic journeys, and it’s never a smooth one. Life never is smooth, in case you hadn’t noticed, and this is art, imitating life.

Next Page »

THE BIG CLOCK. Paramount, 1948. Ray Milland, Charles Laughton, Maureen O’Sullivan, George Macready, Rita Johnson, Elsa Lanchester, Harry Morgan, with uncredited appearances by Noel Neill and Ruth Roman. Screenplay: Jonathan Latimer, based on the novel by Kenneth Fearing. Director: John Farrow.

THE BIG CLOCK. Paramount, 1948. Ray Milland, Charles Laughton, Maureen O’Sullivan, George Macready, Rita Johnson, Elsa Lanchester, Harry Morgan, with uncredited appearances by Noel Neill and Ruth Roman. Screenplay: Jonathan Latimer, based on the novel by Kenneth Fearing. Director: John Farrow.

RELENTLESS. Columbia, 1948. Robert Young, Marguerite Chapman, Willard Parker, Akim Tamiroff, Barton MacLane, Mike Mazurki, Clem Bevans. Based on the novel Three Were Thoroughbreds by Kenneth Perkins. Director: George Sherman.

RELENTLESS. Columbia, 1948. Robert Young, Marguerite Chapman, Willard Parker, Akim Tamiroff, Barton MacLane, Mike Mazurki, Clem Bevans. Based on the novel Three Were Thoroughbreds by Kenneth Perkins. Director: George Sherman.