Wed 24 Dec 2025

Movie Review: THE MASK OF DIMITRIOS (1944).

Posted by Steve under Reviews , Suspense & espionage films[3] Comments

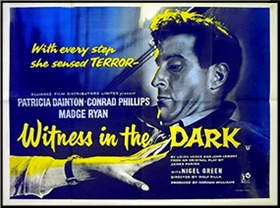

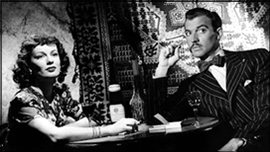

THE MASK OF DIMITRIOS. Warner Brothers, 1944. Peter Lorre, Sydnay Greenstreet, Zachary Scott. Faye Emerson, Steven Geray. Screenplay by Frank Gruber, based on the novel A Coffin for Dimitrios, by Eric Ambler. Director: Jean Negulesco.

When a mystery writer named Leyden (Peter Lorre) is shown the body of a man identified as Dimitrios Makropoulos (Zachary Scott) in a morgue in Istanbul, he becomes obsessed in learning more about the man’s career as an international spy and criminal agent.

Much of the film that follows comes in the form of a series of flashbacks taking place across Europe and finally to Paris, where a man who calls himself Peters (Sydney Greenstreet) makes him an offer that moneywise is hard to refuse.

While the movie follows the book extremely well (as I recall), the stories that have taken place in the life of Dimitiros are, while interesting in themselves, tend to meander a little. Until, that is, the setting changes to that of a small apartment in Paris, when the pairing of Peter Lorre and Sydney Greenstreet and the plans they make together (and how those plans work out) make for an insidiously sinister plot in true film noir fashion.

Those two actors, when playing in the same film, are more, somehow, than their individual roles, a fact that is difficult to explain, but together they were the best in the crime and espionage business, filmwise at least.

___

PLEASE NOTE: While I have done my best to avoid telling you too many details of the story, the clip provided above comes toward thee end of the film. As such, if you have not seen the movie, and you think you might care to, please watch the clip judiciously.