February 2010

Monthly Archive

Sun 28 Feb 2010

REVIEWED BY WALTER ALBERT:

JAMES FRANCIS DWYER – The White Waterfall. Doubleday Page & Co., 1912; illustrated by Charles S.Chapman. W. R. Caldwell & Co., hc, International Adventure Library: Three Owls Edition. Serialized in The Cavalier in four parts, beginning 13 April 1912. Readily available in various Print on Demand editions and as an online etext.

Australian writer Dwyer was a welcome regular in Blue Book Magazine in the 1930s, and this early South Seas adventure novel is a fine example of his robust, colorful narrative style.

The remote, isolated island to which the characters travel, is thought to be uninhabited, but there are structures that pre-date the memory of any race that left written records, and a small group of natives perform ceremonies and make human sacrifices in the name of some savage God. This may remind some of a certain celebrated RKO film released in 1933, but the terrors are all too,human and no giant remnants of an earlier age live in the depths of the jungle.

The protagonist, and narrator, Jack Verslun, an itinerant seaman, is hired to serve on a ship chartered by Professor Herndon, an obsessive scientist who has brought along his two attractive daughters on what turns out to be an ill-advised and dangerous voyage to “The Isle of Tears,” which a rough-looking rogue named Leith has promised the Professor will yield scientific wonders that will make his reputation.

The party, aside from a largely native crew, is completed by Will Holman, a feisty young American who — the son of the owner of the chartered boat they are traveling on — is along for the heck of it and for the love of the younger of the two Herndon girls, Barbara. An older daughter, Edith, is useful for completing a quartet that I needn’t spell out for you.

They reach the island after a terrific storm and when Jack is ordered to stay on the boat while Leith takes a small party to the island, concerned about Leith’s intentions, he jumps ship, catches up with the party and finds himself, Will, and the Professor and his daughters, in a situation that takes them to the brink of disaster.

Dwyer is not, perhaps, as polished a stylist as John Russell, who wrote notable stories about adventures in the South Seas, but the slightly, pulpy cast of his story is perfectly pitched to drawn in a sympathetic reader, with the pace, once the horror of Leith’s intentions becomes clear, resembling the frantic drive of the flight through the jungle to the ship and escape of the earlier noted King Kong.

Editorial Comment: A brief biography of the author appears online at the Pulprack website, with another appearing here.

And of special note to anyone reading this blog is The Spotted Panther, also by Dwyer, has recently been published in a handsome softcover edition by Black Dog Books. Highly recommended!

Sun 28 Feb 2010

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[4] Comments

REVIEWED BY TINA KARELSON:

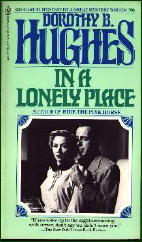

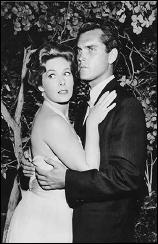

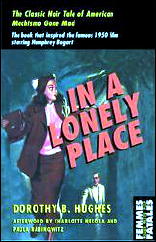

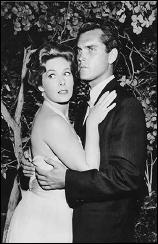

DOROTHY B. HUGHES – In A Lonely Place. Duell Sloan and Pearce, hardcover, 1947. Paperback reprints include: Pocket #587, 1949; Bantam 1979, Carroll & Graf, 1984; Feminist Press, 2003.

Film: Columbia, 1950. Humphrey Bogart (Dixon Steele), Gloria Grahame (Laurel Gray), Frank Lovejoy (Det. Sgt. Brub Nicolai).

If you’ve seen the movie, which happens to be one of my favorites, know this: the book is completely different, but even better.

Set in post-war L.A., the story is told in the third person, entirely from the point of view of Dix Steele. Dix is one of the lost men — someone who thrived in uniform, in danger, but who is now adrift, pretending to be a writer but living mostly on remittances from a wealthy uncle.

When beautiful divorcee Laurel Gray comes into his life, he falls deeply in love and begins to heal, just a little. But Laurel begins to fear Dix, and she takes her concerns to Dix’s friend Brub Nicolai and his astute wife Sylvia. An old war chum of Dix’s, Brub is now an L.A. cop investigating a series of strangulation murders.

As a crime story, this book starts out chillingly and compellingly, and becomes more so with each passing page.

As a piece of social fiction, it paints a fascinating picture of post-war America, contrasting the disenchantment and isolation of some returning soldiers with the orderly, energetic, sociable world of recognizable “Greatest Generation” types like the Nicolai’s, who successfully fought a war and now want to build an orderly, peaceful world at home and also value having a good time — driving, dining, drinking and dancing.

The prose is Hemingway-esque in its spareness. The integrity of the POV is scrupulous.

This is one of the great American novels of the mid-20th century. If Hughes isn’t taught in colleges, she should be.

Sun 28 Feb 2010

Posted by Steve under

Publishers[5] Comments

Three months after the imprint’s launch, Ostara Publishing has issued four more titles in their print-on-demand Top Notch Thrillers series which “aims to revive Great British thrillers which do not deserve to be forgotten.”

The new titles, originally published in Britain between 1962 and 1970, were selected by crime writer and critic Mike Ripley, who acts as Series Editor for TNT:

The Tale of the Lazy Dog by Alan Williams is a brilliant heist thriller set in the Laos-Cambodia-Vietnam triangle in 1969 as a mis-matched gang of rogues and pirates attempt to steal $1.5 billion in used US Treasury notes.

Time Is An Ambush is a delicate, atmospheric study of suspicion and guilt set in Franco’s Spain, by Francis Clifford, one of the most-admired stylists of the post-war generation of British thriller-writers.

A Flock Of Ships, Brian Callison’s bestselling wartime thriller of a small Allied convoy lured to its doom in the South Atlantic, was famous for its breathless, machine-gun prose and was described by Alistair Maclean as: “The best war story I have ever read.”

The Ninth Directive was the second assignment for super-spy Quiller (whose fans included Kingsley Amis and John Dickson Carr), created by Adam Hall (Elleston Trevor) and is a taught, tense thriller of political assassination which pre-dated Day of the Jackal by five years.

Announcing the latest batch of reissues, Mike Ripley said: “Our new titles are absolutely in line with the Top Notch ethos of showing the range and variety of thrillers from what was something of a Golden Age for British thriller writing. They range in approach from slow-burning suspense to relentless wartime action and feature obsessive, super tough, super cool spies and some tremendous villains. Above all, they are characterised by the quality of their writing, albeit in very different styles.

“When first published, these titles were all best-sellers and their authors are among the most respected names in thriller fiction. Many readers will welcome these novels back almost as old friends and hopefully a new generation of readers will discover them for the first time.”

Top Notch Thrillers are published as trade paperbacks with a RRP of £10.99.

Sun 28 Feb 2010

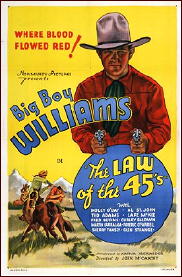

THE LAW OF THE 45’s. Normandy Pictures, 1935. Guinn ‘Big Boy’ Williams (Tucson ‘Two-Gun’ Smith), Molly O’Day, Al St. John (Stoney Martin), Ted Adams, Lafe McKee, Fred Burns. Screenplay: Robert Emmett Tansey, based on the novel by William Colt MacDonald (Law of the Forty-Fives, Covici Friede, 1933). Director: John P. McCarthy.

To start off, to put off the inevitable and to put it bluntly, there is absolutely no reason anyone should watch this Bottom of the Barrel B-Western movie except for historical reasons.

To wit: although not officially part of the canon, and even though only two of them show up, and one of them has the wrong name, this is the first of the “Three Mesquiteers” movies, of which there were 51 more to come, beginning in 1936 and ending in 1943.

Although many players played the three cowboys over the years, the ones I remember most are Robert Livingston as Stony Brooke, Ray Corrigan as Tucson Smith, and Max Terhune as Lullaby Joslin. You may have your own favorite threesome, but as much as I liked Bob Steele as a cowboy star (Tucson Smith in the last 13 of them), the ones above were mine.

Some movies with a running time of 57 minutes have so much crammed into them that each and every scene has a crucial part of the story line in it. Not so with Law of the .45’s. It is the longest 57 minutes I can remember sitting through since grad school. The acting is a mixture of old-fashioned silent movie stars trying to figure out what the microphone is doing there, with pauses for emphasis that you could plow an 18-wheeler through, while other of the players seem to have taken nicely to the new technology, speaking in normal tones and normal rhythms.

Story: a crooked lawyer is apparently behind the gang of outlaws terrorizing the valley where Tucson and Stoney are bringing their herd of cattle, and the latter agree to work for Joan Hayden (Molly O’Day) and her father (Lafe McKee) to bring peace and justice back to the land again.

Other than that, there is little but cowboys riding here and there in the hills, ranches being burned to the ground and cattle stampeding (as cattle are wont to do) — all very exciting, or it would be if you care for watching cowboys riding here and there in the hills, sometimes at very high speeds. There is also a group of singing wranglers, unnamed as a group or individually in the movie’s credits, but their identities can be found on the know-all IMDB page for the film.

As for Guinn ‘Big Boy’ Williams, he gets to grimace and squint a lot, but on the other hand, he also gets the girl.

Sat 27 Feb 2010

A MOVIE REVIEW BY DAVID L. VINEYARD:

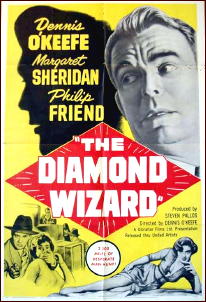

THE DIAMOND WIZARD. United Artists, US/UK, 1954. Released as The Diamond in the UK. Dennis O’Keefe, Philip Friend, Margaret Sheridan, Alan Wheatley, Francis De Wolff, Paul Hartmuth. Screenplay: John C. Higgins. Story Dennis O’Keefe, based on the novel Rich Is the Treasure (1952) by Maurice Procter. Directed by Dennis O’Keefe & Montgomery Tully.

When a US Treasury agent is killed by British smugglers who have stolen a million dollars, a perfect diamond is found in his mouth. Perfect except for one thing — it’s artificial; and perfect artificial diamonds are a threat to both the British and American economies.

So Treasury Man Joe Dennison (Dennis O’Keefe) is dispatched to England to team up with Special Branch’s Inspector Hector ‘Mac’ McClaren (Philip Friend) to track down the smuggler (Francis De Wolff) who is using a million dollars in stolen money to buy the artificial diamonds.

The case gets more complex when lovely Marline Miller (Margaret Sheridan) shows up. She’s the niece of nuclear physicist Dr. Miller (Paul Hartmuth) who has gone missing — and once a romantic connection for Dennison.

Following a handful of clues the police begin to tie the two cases together ending in an explosive climax somewhere between Edgar Wallace and Ian Fleming as they uncover something more sinister than flooding the diamond market afoot.

This little film, directed by O’Keefe during a brief period when he fled to England like many other American actors of the period, is nothing new or great, but entertaining and loosely based on a novel by British mystery writer Maurice Procter, itself expanded from a novella “The Million Pound Note.” (Proctor is best known for his series of Inspector Harry Martineau police procedural novels.) The thrills are of the standard variety, but well enough done.

There’s the usual master criminal, the usual mad scientists, some nasty thugs, and two tough honest cops. The difference between the American and British police style is played as complimentary rather than conflicting, and the scenes of the artificial diamonds being created have the nice SF touch of the kind that used to dominate German Expressionist cinema.

This is an entertaining little film, not much more than a programmer, but coming in at 83 minutes it moves nicely and never really slows down for a breather. O’Keefe probably got the inspiration for this from his American film Walk a Crooked Mile (1948; Gordon Douglas, dir.) teaming him with Louis Hayward, with the latter the Scotland Yard man out of place in the US.

Sat 27 Feb 2010

Posted by Steve under

Covers ,

Reviews[6] Comments

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

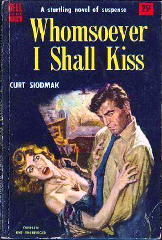

CURT SIODMAK – Whomsoever I Shall Kiss. Crown Publishers, hardcover, 1952. Paperback reprint: Dell 756, 1954.

Quite without meaning to, I read two novels of Romantic Suspense last year. Curt Siodmak’s Whomsoever I Shall Kiss was the first, and it starts off well, with Royal Ludovici, a former small-time grifter and guy-with-a-funny-name, who lives by making himself useful to the very rich.

In Italy to find proof of an heiress’s death (and thereby speed an inheritance to a distant relation), Royal finds the heiress very much alive and maybe suffering from amnesia … or maybe not.

Well, Royal is suave, good-looking and unattached, the heiress is lovely, lonely and broken-hearted, so the only question for Royal is whether to get her to marry him, then tell her she’s wealthy, or to make sure that reports of her death weren’t so far wrong after all.

It’s a nice set-up for a story, and I expected to see something interesting spun out of it by a hack with Siodmak’s credentials, but he doesn’t do much with it; in fact, he does practically nothing at all. Pages go by filled with sight-seeing, passionate embraces, tearful farewells, torrid embraces and even a bit from The Wolfman, all to very little effect. By the time Siodmak tacked an unsatisfactory ending on, I wasn’t even interested enough to be disappointed.

Sat 27 Feb 2010

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[13] Comments

A REVIEW BY RAY O’LEARY:

ANDREW GARVE – A Hole in the Ground. Dell, paperback reprint D275, 1959; Great Mystery Library #21. UK edition: Collins Crime club, hardcover, 1952. US First Edition: Harper & Brothers, 1952. Also: Pan #343, UK, pb, 1955; Lancer 72-730, US, pb, 1964.

I’d read quite a few of Andrew Garve’s novels, but I never heard of this one until I came across it on a sidewalk table at Barnes and Noble’s.

Laurence Quilter is the Labour Party Member of Parliament for the area around the town of Blean in West Cumbria. He has a wealthy background and a wife named Jane. They have recently donated his family’s large house to the National trust and moved into a cottage on the estate and he is up for re-election. He is bitterly disappointed that he has never been given a position in the ruling Labour Party’s government.

While looking through some old papers from his donated house, he comes across a crude map made by his great grandfather nearly a century before. It seems to indicate that somewhere on his land is the entrance to a large cave his ancestor discovered but didn’t make public.

While his wife is away visiting friends, he discovers the entrance to the cave and decides to contact a young School Master/ spelunker he knows named Peter Antsley. They explore the cave and find an underground river some 200+ feet below ground reached by going down rope ladders.

On their second trip, Quilter takes a nap while Antsley does some exploring on his own. Outside, a storm rages which causes the underground river to flood and when Antsley’s foot gets caught and he calls for help, Quilter is too afraid to help him and Antsley drowns.

Quilter decides to cover up his cowardice and tell no one. He takes his wife on vacation to France but when there is a mining accident in his district, he returns home leaving her. While in France they had meet Ben Traill, an American geologist who works for an oil company.

With Quilter in England, Jane and Ben spend so much time together that they fall in love. Finally, Jane decides to go home to confront her husband and from there, during the last 30 pages or so, the story takes a turn into left field.

You might think that Quilter has been spending his time further covering up Antsley’s death, even though the dead man’s wallet has been found and the police know that Antsley had been in touch with Quilter shortly before he disappeared, but that isn’t the case at all.

Let’s just say there’s an unnamed reference to a well-known British spy case that first hit the headlines circa 1950 and, though Garve didn’t know it at the time, the case would return two more times to the headlines in the ensuing decades.

I don’t know if Garve wrote himself into a corner and came up with this lollapoloosa of an ending to get out or what. All I know is that this is the poorest book by Garve I’ve read. Fortunately, he went on to write much better stuff.

Sat 27 Feb 2010

A TV Review by MIKE TOONEY:

“Don’t Look Behind You.” An episode of The Alfred Hitchcock Hour (Season 1, Episode 2). First air date: 27 September 1962. Jeffrey Hunter, Vera Miles, Abraham Sofaer, Dick Sargent, Alf Kjellin, Ralph Roberts, Mary Scott, Madge Kennedy. Teleplay:

Barré Lyndon, based on a novel by Samuel Rogers. Director: John Brahm.

Daphne (Vera Miles) is late for a dinner date and, like Little Red Riding Hood, decides to take a shortcut through the woods, which almost proves fatal because a serial killer is stalking her.

She does make it unmolested, however. Within the next few minutes after her arrival, no fewer than four men show up at the party. She doesn’t know it at the time, but one of the four has already committed murder and another one will soon be making an attempt on her life…

Maybe it’s just me, but this one doesn’t quite gel. True, the characters’ intentions are adequately foreshadowed, but the whole thing seems wonky and unconvincing.

Vera Miles’ criminous credits include 23 Paces to Baker Street (1956), The Wrong Man (1956), Psycho (1960), three appearances on The Name of the Game, one on the Jim Hutton Ellery Queen, and three episodes of Murder, She Wrote.

Jeffrey Hunter appeared in Fourteen Hours (1951), A Kiss Before Dying (1956), Key Witness (1960), Man-Trap (1960), and 26 episodes of the Temple Houston TV series (1963-64).

Hulu: http://www.imdb.com/video/hulu/vi685244441/

Editorial Comment: The pilot for the Temple Houston TV was titled The Man from Galveston (1963) and was considered so well done that it was released theatrically. David Vineyard reviewed it here on the blog last July.

Fri 26 Feb 2010

HAD I BUT KNOWN AUTHORS #1: ANITA BLACKMON

by Curt J. Evans

In Murder for Pleasure, the essential 1941 study of the detective story as a literary form, Howard Haycraft listed ten women authors who constituted what he called the “better element”of the so-called HIBK, or Had I But Known, school of mystery fiction, which was founded by Mary Roberts Rinehart (1876-1958) over three decades earlier with the publication of her hugely popular debut novel, The Circular Staircase (1908).

The Had I But Known school of mystery fiction, as it was so dubbed by (mostly male) mystery critics after the term was used by Ogden Nash in a satirical 1940 poem, typically included mysteries with female narrators given to digressive regrets over the things they might have done to prevent the novel’s numerous murders, had they only been able to see the dire consequences of their inaction.

Haycraft’s list of the ten premier Rinehart followers includes several names still fairly well-known to genre fans today, namely Mignon Eberhart, Leslie Ford and Dorothy Cameron Disney, but also more obscure names as well.

Three of these writers, Charlotte Murray Russell and the sisters Constance and Gwenyth Little, have recently had works reprinted and resultingly undergone some reader revival, but the remaining four, Anita Blackmon, Margaret N. Armstrong, Clarissa Fairchild Cushman and Medora Field, remain almost entirely forgotten.

Over the next few weeks I plan to highlight genre work by these forgotten HIBK authors. I begin with Anita Blackmon.

Anita Blackmon (1893-1943) published two mystery novels, Murder a la Richelieu (1937) and There Is No Return (1938). In the United States, both of Blackmon’s mysteries were published by Doubleday Doran’s Crime Club, one of the most prominent mystery publishers in the country.

Murder a la Richelieu was published as well in England (as The Hotel Richelieu Murders), France (as On assassine au Richelieu) and Germany (as Adelaide lasst nicht locker), while There Is No Return was published in England also (under the rather lurid title The Riddle of the Dead Cats).

In classic HIBK fashion, Blackmon employed a series character in both novels, a peppery middle-aged southern spinster named Adelaide Adams (and nicknamed “the old battle-ax”).

In the opening pages of Adelaide Adams’ debut appearance, Murder at la Richelieu, Anita Blackmon signals her readers that she is humorously aware of the grand old, much-mocked but much-read HIBK tradition that she is mining when she has Adelaide declare, “had I suspected the orgy of bloodshed upon which we were about to embark, I should then and there, in spite of my bulk and an arthritic knee, have taken shrieking to my heels.”

Yet, sadly, Adelaide confides, “there was nothing on this particular morning to indicate the reign of terror into which we were about to be precipitated. Coming events are supposed to cast their shadows before, yet I had no presentiment about the green spectacle case which was to play such a fateful part in the murders, and not until it was forever too late did I recognize the tragic significance back of Polly Lawson’s pink jabot and the Anthony woman’s false eyelashes.”

Well! What reader can stop there? Adelaide goes on with much gusto and foreboding to relate the murderous events at the Hotel Richelieu, a lodging in a small southern city (clearly Little Rock, Arkansas; see below). Adelaide is a wonderful character: tough on the outside but rather a sentimentalist within, given to the heavy use of cliches yet actually rather mentally acute.

The life in and inhabitants of the old hotel are well-conveyed, the pace and events lively and the mystery complicated yet clear (and at the same time played fair with the readers). Perhaps most enjoyable of all is the author’s strong sense of humor, ably conveyed through Adelaide’s memorable narration.

Blackmon clearly knows that HIBK tales frequently are implausible and even silly in their convolutions and she has a a lot of fun with the conventions. Readers should have a lot of fun as well. Murder a la Richelieu emphatically deserves reprinting.

Blackmon’s follow-up from the next year, There Is No Return, is less successful. This tale finds Adelaide coming to the rescue of a friend, Ella Trotter, embroiled in mysterious goings-on involving spiritual possession at a backwoods Ozarks hotel, the Lebeau Inn (in fact the novel could well have been called Murder a la Lebeau).

Though Return opens with yet another splendid HIBK declaration in the part of Adelaide ( “As I pointed out, to no avail, when the body of the third disemboweled cat was discovered in my bed, had I foreseen the train of horrible events which settled over that isolated mountain inn like a miasma of death upon the afternoon of my arrival, I should have left Ella to lay her own ghosts”), the novel is less amusing than Richelieu, its character less interesting and its mystery less cogently presented and credible.

Yet it is still fun to encounter the old battle-ax one final time.

When Howard Haycraft published Murder for Pleasure in 1941, he clearly classed Blackmon as a major figure in the HIBK school, though she in fact had not published a mystery novel in three years. Two years later Blackmon would die at the age of fifty, and her fiction would be largely forgotten. I have discussed her genre work a bit, but have so far left unanswered this question: who was Anita Blackmon?

Anita Blackmon was born in 1893 in the small eastern Arkansas town of Augusta. The daughter of Augusta postmaster and mayor Edwin E. Blackmon and his wife, Augusta Public School principal Eva Hutchison Blackmon, both originally from Washburn, Illinois, Anita Blackmon revealed a literary bent from a young age, penning her first short story at the age of seven.

By all accounts, Blackmon grew up into a vivacious, attractive, outgoing young woman. The future novelist graduated from high school at the age of fourteen and attended classes at Ouachita College and the University of Chicago. Returning home from Chicago, she taught languages in Augusta for five years before moving to Little Rock, where she continued to teach school.

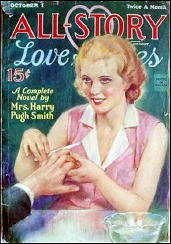

In 1920, Blackmon left teaching and married Harry Pugh Smith in Little Rock. The couple moved to St. Louis, where Blackmon had an uncle who served as a St. Louis and San Francisco Railroad vice president, and in 1922 Blackmon published the first of what would be over a thousand short stories. Blackmon’s short stories appeared in a diverse collection of pulps, including Love Story Magazine, All-Story Love Stories, Cupid’s Diary, Detective Tales and Weird Tales.

Blackmon began publishing novels in 1934 with a work entitled Her Private Devil, one that provoked some scandalized talk back in Augusta. Devil was published by William Godwin, a press, as described by Bill Pronzini, that specialized in titillating novels that pushed the sexual envelope of the day.

Godwin titles by other authors in the writing stable such as Delinquent, Unmoral, Illegitimate, Indecent, Strange Marriage and Infamous Woman give some idea of the nature of most Godwin fiction.

Blackmon’s book, which detailed the unhappy life of a southern small-town girl who gives into her strong sexual desires, is fairly bold, but by no means a “dirty” book. In actuality it is a serious study of a troubled young woman handled with considerable sensitivity and not especially explicit by today’s standards. Still, the book raised something of a stir in conservative Augusta, with some in the town expressing disapproval.

Over the next few years Blackmon published traditional, mainstream novels under the name Mrs. Harry Pugh Smith, some of which had been previously serialized, before concluding her run with her two mystery novels, published, like Her Private Devil, under her maiden name.

The best known of the Mrs. Harry Pugh Smith novels was Handmade Rainbows, a tale of middle class Depression-era life in small southern town very like Augusta. Part of the enjoyment one gets from Blackmon’s better novels stems from the author’s effective depiction of unique southern local color.

Blackmon’s Murder a la Richelieu clearly is set in Little Rock, where there was in fact a Richelieu Hotel, while There Is No Return is set far in the Ozarks. Certainly many Golden Age mysteries with Arkansas settings do not come to my mind!

Why Anita Blackmon produced no more Adelaide Adams mysteries in her last five years of life is a mystery itself. Blackmon died after a lengthy illness in a nursing home in Little Rock, where she moved after the death of her husband.

Perhaps under the circumstances she was not up to plotting and writing another full-length mystery novel, though she is said to have continued writing until shortly before her death. Though Blackmon’s mystery novel output is small, Murder a la Richelieu, at least, merits reprinting as a significant example of an HIBK tale.

Also worth noting are the many now-unknown short stories that Blackmon wrote, some of which (those published in Detective Tales) might well be of interest to mystery genre fans. Clearly, further delving is in order!

NOTE: Information on Anita Blackmon’s life was drawn from Woodruff County Historical Society, Rivers and Roads and Points in Between 3 (Fall 1975), pp. 21-22 and interviews with Rebecca Boyles and Virginia Boyles. Special thanks for his generous help to Kip Davis, Augusta City Planner.

Bibliography (Short Fiction; Incomplete) —

BLACKMON, ANITA

* * Glory That Flamed, (ss) Four Star Love Magazine Mar 1937

* * The High Heart, (ss) Cupid’s Diary Jun 28 1927

* * Love’s Precious Secret, (ss) Sweetheart Stories Feb 17 1926

* * The Mystery of Tip Top Inn, (sl) Sweetheart Stories Apr 14 1926

* * Under Another’s Name, (ss) Cupid’s Diary Dec 2 1925

* * With Hearts Aflame, (nv) Sweetheart Stories Mar 3 1926

SMITH, MRS. HARRY PUGH

* * Angel Face, (ss) Love Story Magazine Nov 27 1926

* * The Book of Death (nv) Weird Tales, Nov 1924

* * The Burnt Offering (?) Mystery Magazine, Aug 1 1922

* * Carnival Man, (ss) All-Story Love Stories Apr 15 1933

* * Chained [Part last of ?], (sl) All-Story Love Stories Nov 30 1935

* * Cheated, (ss) Cabaret Stories Jan 1929

* * The Colonel’s Daughter, (ss) Sweetheart Stories May 20 1930

* * A Cottage for Two, (ss) All-Story Dec 14 1929

* * The Devil’s Signet, (ss) Love Story Magazine Oct 31 1925

* * Double Motive (?) Detective Classics June 1930

* * Fettered, (ss) Love Story Magazine Sep 25 1926

* * Firecracker Kathy, (nv) All-Story Love Stories Jul 1 1932

* * Flower of Dusk, (ss) Cupid’s Diary Jun 12 1929

* * The Gay Deceiver, (ss) Love Story Magazine Oct 29 1927

* * Ghost Between [Part last of ?], (sl) All-Story Love Stories Feb 16 1935

* * Her Snobbish Dude, (ss) Far West Romances Jan 1932

* * The Hermit (?) Detective Tales Nov 16/Dec 15 1922

* * The Hindu, (ss) Detective Tales Feb 1923

* * An Interrupted Engagement, (ss) Love Story Magazine Dec 18 1926

* * The Jeweled Pin (?) Detective Tales Apr 1924

* * Jezebel, (ss) Breezy Stories Mar #2 1925

* * Little Lost Bride, (ss) Sweetheart Stories Jul 1935

* * Long Live the King!, (ss) Cupid’s Diary Dec 12 1928

* * Love at Last, (ss) Love Story Magazine Jan 2 1926

* * Love by Accident, (ss) All-Story Love Stories Apr 1 1933

* * The Love Fued, (ss) Love Story Magazine Nov 20 1926

* * Love’s Upward Trail, (ss) Love Story Magazine Jul 30 1927

* * The Marriage of Michael Malloy, (nv) All-Story Love Stories Mar 23 1935

* * Marry for Love, (ss) Sweetheart Stories Mar 1937

* * Marry Him If You Dare!, (sl) All-Story Love Stories Jan 30 1937

* * Maybe It’s Love, (sl) All-Story Love Stories Sep 19, Sep 26, Oct 3, Oct 10, Oct 17, Oct 24 1936

* * My Lady’s Dressing-Table, (vi) Breezy Stories Feb 1923

* * Object, Matrimony, (ss) All-Story Love Stories May 15 1933

* * One True Love [conclusion], (sl) All-Story Love Stories Sep 8 1934

* * The One-Track Heart, (sl) All-Story Love Stories Jan 18 1936

* * The Pride of Darcy, (ss) Love Story Magazine Nov 21 1925

* * Ranch Paradise, (nv) Street & Smith’s Far West Romances Jun 1932

* * The Sting of the Scorpion, (ss) Action Stories Feb 1923

* * A Tangled Skein, (ss) Love Story Magazine Mar 27 1926

* * The Town’s Bad Boy, (sl) All-Story Love Stories Mar 13, Mar 20, Mar 27, Apr 3 1937

* * With This Ring, (nv) All-Story Love Stories Jun 15 1932

* * The Yellow Dog (?) Detective Tales Oct 16 1922

SOURCES: The FictionMags Index; Mystery, Detective & Espionage Fiction, 1915-1974, Cook & Miller.

Fri 26 Feb 2010

Posted by Steve under

Awards ,

General[2] Comments

According my daily stat monitor, yesterday was the first day this blog has gone over 500 visitors and 900 pages viewed. Each of two numbers have been topped on one or two occasions before, but this the first time that both heights have been attained on the same day.

The post that’s gained the most attention over this past week, which may have had something to do with it, has been Mike Nevins’ column on Margery Alllingham’s “Mr Campion” short stories. I don’t know if the number of people who’ve read that post will attract the attention of a publisher, but it would be nice if it happened.

The other honor that M*F the blog has recently been given is being included in the Court Reporter‘s list of “50 Best Blogs for Crime & Mystery Book Lovers.” You now know what one of them is. Follow the link to learn what the other 49 are. Some of the others I go to every day myself, and some of those I haven’t been, I will from now on.

Next Page »