REVIEWED BY MIKE TOONEY:

(Give Me That) OLD-TIME DETECTION. Autumn 2025. Issue #70. Editor: Arthur Vidro. Old-Time Detection Special Interest Group of American Mensa, Ltd. 34 pages (including covers).

AS usual, Old-Time Detection (OTD) succeeds in keeping classic detective fiction alive and interesting. In this issue diversity is the theme, with coverage of detecfic authors from Conan Doyle to some of the latest practitioners of the genre being highlighted.

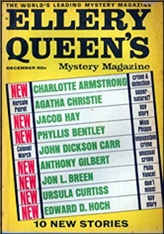

First up is an EQMM interview with Robert Twohy, whose approach to writing is basically character-centric: “I’ve tried to write something to approach it [‘Red-Headed League’], and haven’t yet — but the fun is in the quest.” (See the Fiction selection below for more by this author.)

J. Randolph Cox talks about Arthur Train, now almost forgotten but once very popular in the first decades of the 20th century.

Next we have a reprint of Martin Edwards’s introduction to Peter Shaffer’s THE WOMAN IN THE WARDROBE, which Robert Adey later characterized as “the best post-war locked-room mystery . . . [with] a brilliant new solution.”

Everybody has to start somewhere. Francis M. Nevins exhibits his usual high-quality scholarship in “The Pulp Origins of John D. MacDonald,” highlighting that soon-to-be-popular author’s early days: “MacDonald was the last great American mystery writer to hone his storytelling skills in the action-detective pulps as Hammett and Chandler and Gardner and Woolrich had done before him.”

Jon L. Breen’s reviews of books (ten of them from the Walker Reprints Series) in “40-Plus Years Ago” take us from familiar mystery fiction old reliables like Pierre Chambrun, to obscure eccentrics like Inspector James and Sergeant Honeybody.

In Part II of Michael Dirda’s “Mystery Novels So Clever You’ll Read Them Twice,” he points us to modern-day examples of stories that manage to surprise the reader. After all, he says, “A mystery that doesn’t surprise is hardly a mystery at all.”

Arthur’s Fiction selection is Robert Twohy’s ingenious “A Masterpiece of Crime,” in which a police detective and a detecfic enthusiast solve a murder, with a certain very well-known detective making a cameo appearance.

In world-class Agatha Christie expert Dr. John Curran’s latest “Christie Corner,” he informs us of the activities pertaining to the latest International Agatha Christie Festival, including a nostalgic look back at the Joan Hickson-Miss Marple TV series from forty years ago and a look forward to an upcoming print adaptation of Miss Marple; another upcoming TV “re-imagining” of Mrs. Christie’s popular married sleuthing duo, Tommy and Tuppence (“Sadly, Christie fans are all too aware of what ‘re-imagining’ means”); and yet another upcoming event next year, characterized as “the biggest exhibition held in the last twenty years to celebrate Christie’s writing,” timed to coincide with the centenary of THE MURDER OF ROGER ACKROYD.

In “Collecting,” Arthur Vidro recounts the varied experiences of mystery and detecfic book collectors, one of whom undoubtedly speaks for a multitude: “It’s hard to say goodbye to favorites.”

Next, in “Sherlock Holmes in Comics” Arthur deals on a personal level with the sporadic career of the Sage of Baker Street in that worthy’s four-color mass market exposures.

Fifty years ago there was a mini-boom in Sherlock Holmes-related fiction and non-fiction paperbacks, and Charles Shibuk summarizes it in “The Sherlockian Revolution.”

Next Arthur Vidro offers a mini-review of his first John Rhode novel and finds it most satisfactory.

The readers have their say, especially about how the latest issue of OTD did not neglect the contributors to detective fiction from Fair Albion.

And finally, Arthur confronts us with a mystery puzzle that anyone who’s been watching prime time crime TV programs for the last fifty years should find a cinch. (Yeah, right.)

Be honest now. Considering everything you’ve just read, don’t you think that the Autumn ’25 OTD might be worth a look?

Subscription information:

– Published three times a year: Spring, summer, and autumn. – Sample copy: $6.00 in U.S.; $10.00 anywhere else. – One-year U.S, subscription rate increase starting with the next issue: $20.00. – One-year overseas: $45.00. – Payment: Checks payable to Arthur Vidro, or cash from any nation, or U.S. postage stamps or PayPal. Mailing address:

Arthur Vidro, editor

Old-Time Detection

2 Ellery Street

Claremont, New Hampshire 03743

Web address: vidro@myfairpoint.net