July 2007

Monthly Archive

Tue 31 Jul 2007

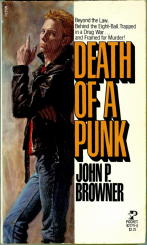

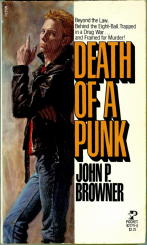

John P. Browner was the author of Death of a Punk (Pocket, pbo, 1980), a PI novel which as you may recall, was profiled here on the blog not so very long ago.

At stated then, and so credited in Al Hubin’s Crime Fiction IV, the other book that Browner is said to have written was Who Killed the Snowman? (Pocket, pbo, 1979).

While Death of a Punk is a book not easily found, it can be obtained if you’re willing to pay the price that’s currently being asked for it online. Or you can wait for it to show up while visiting used bookstores or library sales. It does exist.

On the other hand, there are no copies of Who Killed the Snowman? offered for sale online anywhere at all. The suspicion that there weren’t any to be found began to grow. And who was John P. Browner anyway?

To answer the second question first, Al Hubin, working under the assumption that that was Browner’s real name, reports his findings:

Peoplefinders currently locates three John P Browners; one (age 87) is shown for Orlando, Florida and Deer Park, New York. Another (age 54) is shown for Durham, North Carolina and Sunapee/Claremont, New Hampshire. Either could possibly be the author in question. The third one is not given with an age, and he’s in Honolulu. Since

Death of a Punk is set in NYC, that connects most closely with the 87 year old.

There are a number of John Browners with no middle initials given, who could, I suppose, be candidates.

There are 12 John Browners in the social security death benefit records; none is shown with middle initial P.

There’s nothing very conclusive here, but I agree with Al that the Florida-New York state Browner is the most likely candidate. Unfortunately, no address or telephone number has been obtained for him, and here is where the trail has temporarily ended.

As for Who Killed the Snowman? It doesn’t exist. Here, from Victor Berch, is the evidence:

I decided to check through the volumes of

Paperback Books in Print that I have. In the March 1979 volume was the following entry:

Browner, John. Who Killed the Snowman? 1979. 2.25 (ISBN 0-671-82779-0) PB

Then, in the Spring 1981 volume were the following entries:

Browner, John. Death of a Punk. (Orig) 1980. Write for info (ISBN 0-671-82779-0). PB.

Browner, Who Killed the Snowman? 1979. 2.25 (ISBN 0-671-82779-0) PB

Note that the ISBN numbers are the same for each. I imagine that anyone writing for information would learn from the publisher (PB=Pocket Books), that the title Who Killed the Snowman? had been changed to Death of a Punk.

Mon 30 Jul 2007

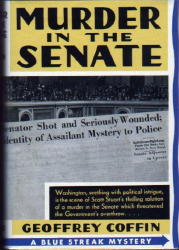

The latest batch of covers uploaded to Bill Deeck’s Murder at 3 Cents a Day website are those for the Dodge Publishing Company, 1935-1938, some of which were designated as “Blue Streak Mysteries.”

Here’s Bill Pronzini’s introduction to the page containing the publisher’s line of detective fiction:

About all I know about Dodge is that they existed from 1935 to 1942, only publishing mysteries between 1935 and 1938. Their specialty seems to have been Westerns, of which about two-score saw print. More than likely, Dodge was yet another publishing casualty of WW II and its paper shortages.

Besides the one shown, other authors and titles in the short-lived series include Theodore Roscoe with two books, one of which is I’ll Grind Their Bones; Joseph T. Shaw’s Blood on the Curb; George Bruce’s Claim of the Fleshless Corpse; and a small handful of others.

In case you were wondering, Geoffrey Coffin was the joint byline of Van Wyck Mason and Helen Brawner, whose series character Inspector Scott Stuart of the US Department of Justice made his first appearance (of two) in Murder in the Senate.

Sat 28 Jul 2007

I’m still on vacation mode, but as I promised I might, I’m posting a short piece on a book that I just discovered that I have but didn’t know anything about until just now. And I can’t wait until September to tell you about it.

It’s a private eye novel, one by John P. Browner, who is in Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin, but about whom he also knows nothing more. The complete entry for the author reads like this:

BROWNER, JOHN P.

* -Who Killed the Snowman? (n.) Pocket Books 1979

* Death of a Punk (n.) Pocket Books 1980 [New York City, NY]

It’s the second book of the pair which I’ve just discovered that I own. I found it in a box in my garage that I opened this afternoon to see what was in it (the box, that is). At the moment there’s not a single copy of Who Killed the Snowman? up for sale on the Internet, and Google brings up not a single mention of it, so I have no idea what it’s about. There is one copy of Death of a Punk on Amazon.com with an asking price of $75.00, but unless you’re more resourceful than I am, all of the other copies you’ll find there or anywhere else will set you back $300 or more. And, yes, you read that right.

A word to the early bird. If the $75 one is gone by the time you read this, you weren’t early enough.

The blurb on the front cover reads as follows: “Beyond the Law, Behind the Eight-Ball, Trapped in a Drug War … and Framed for Murder!”

From the back cover:

ZZZ. Private Work for a Fee.

Complete Discretion Assured.

Leonard Hornblower (212) 699-1848.

Lenny Hornblower. That’s me. $100-a-day plus expenses. Cash up front. Remember, this isn’t a licensed operation. I’ll trace anything, even runaways. For them it’s extra: $150 per, plus.

So when a Mrs. Perlont (“Call me Lisa.”) asked me to find her Blinky, it was just another penny-ante job .. until I started nosing around the East Village puck rock scene and ran into a hot snowstorm: a cocaine heist, a hijacking ring and a know-nothing kid who knew too much to live.

With friends like his, enemies were superfluous. Blinky was a punk rocker with a one-way ticket to Disaster Street. Trouble was, he wanted to take me along for the ride. And so did his stepmom who was willing to reveal everything but what I needed if I was ever going to find the one responsible for the …

DEATH OF A PUNK.

About the “ZZZ.” That’s the first word in the ad that Hornblower puts in the Village Voice every week. Rather than having it show up at the top of the list in the classified section, he makes sure that it appears at the bottom.

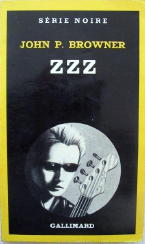

There is a French version of this book, or at least I assume that it’s the same book, my French having disappeared on me about the same time I passed my last French exam, which would have been in 1964 or 1965. Here’s the bibliographic information from Amazon’s French website, along with a cover scan:

Description du livre: Gallimard, 1981. État : Bon état. NRF 248p. N̊1824, première édition. N̊ de réf. du libraire 1928.

Thu 26 Jul 2007

If you’ll check back, I think you’ll see that the Mystery*File blog has been up and running for seven months, as of today.

I didn’t think I had anything to say when I started, but I guess I proved myself wrong. I’m fairly happy with all of the blog entries, and really really pleased with a few of them.

The heading for this particular post says that I’m taking a break, which means that for the most part, I’ll be taking the rest of the summer off. I’ve not run out of things to say. Far from it! It’s the other way around, by a full 180 degrees — and I’m totally frustrated that I’ve not been able to follow through on a large number of things I’ve been planning on doing and just haven’t gotten to, yet.

But the time has come for a short recess from blogging and to do a good many other more mundane things instead, like cleaning the garage and organizing my book and magazine collection, as if those two chores were not really one and the same thing. I also have a basement full of books plus three storage areas and they are all calling me, and not so softly in recent days and weeks.

And there are a few other matters which will keep me away from this keyboard for a while. Working outside and doing a general long-delayed yard clean-up, scrubbing the deck, and believe it or not, no painting. I hate painting.

I’m not going away. I’ll answer emails — even reply to some emails that I haven’t managed to get to in the last few months or so — and there will be an occasional post when an article or long piece is ready and it just doesn’t want to wait until September.

I will also be working on the Addenda to Al Hubin’s Crime Fiction IV and continuing to add cover images to Bill Deeck’s Murder on 3 Cents a Day website, so I’ll not be all that far away from the computer, after all.

A big thank you is due from me to all of the people who’ve stopped by, especially those who’ve left comments and have emailed me behind the scenes. A number of friends have been reunited through these blog entries, for example, and moments such as those have pleased me more than almost anything else. Thanks, too, to everyone who’s contributed. You know who you are, and I’m counting on you for more.

Except for, as I say, an occasional post, you’ll hear from me again in the fall. Watch this space.

Thu 26 Jul 2007

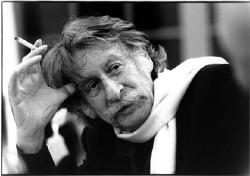

Taken from an obituary which appeared in the online edition of The Guardian:

“The dramatist and writer George Tabori, who has died aged 93, was one of the last of the generation of writers forced into exile by the Third Reich. Hungarian by birth, writing in English and directing and occasionally acting in German, he combined experience of British and American life with the cosmopolitan cultural traditions of central Europe. Starting as a maverick director in 1970, he was the most widely performed modern writer in the German theatre by 1992.

“From 1943 until 1947 he worked for the BBC in London, where he took British citizenship [and] had begun to write novels: Beneath the Stone (1945), a thriller written in Jerusalem, Companions of the Left Hand (1946), composed on the boat back from Egypt, and Original Sin, a psychological crime novel set in Cairo. These came to the attention of MGM, which in 1947 signed him as a scriptwriter. He moved in émigré and film circles. With Thomas Mann he tried to set up a film of The Magic Mountain to star Montgomery Clift and Greta Garbo, but in the end he had few Hollywood credits, although he wrote the screenplay for Hitchcock’s I Confess in 1953 and shared a Bafta with Robin Estridge for the screenplay of Anthony Asquith’s The Young Lovers in 1954.”

His entry in Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin, even slightly expanded, is relatively modest:

TABORI, GEORGE (1914-2007 )

* Beneath the Stone. Houghton Mifflin, hc,1945. British title: Beneath the Stone the Scorpion. Boardman, pb, 1945.

* -Original Sin. Houghton Mifflin, hc, 1947. Boardman, hc, 1947. Setting: Cairo.

* The Good One. Permabook M4180, pb, 1960. Setting: West Africa.

Of Beneath the Stone, one online bookseller described it thusly: “The story of two men, a German and an Englishman – captor and captive – who meet for one night in a Balkan valley to dine…”

A Time Magazine review of Original Sin says: “George Tabori […] seems to have written this psycho-thriller with his left foot. A khamseen howls for days in Cairo, wearing tempers thin as the hot, gritty sand seeps through the doors and windows of the pension […] On the fifth morning of the storm, Adela Manasse, wife of the pension’s proprietor, is found dead in her tub, naked and smiling a ‘kindly’ smile. How did she die and why did she smile? Original Sin explores this problem amid swirls of windblown sand and snarls of plot typical of Cosmopolitan magazine fiction – which is, in fact, what this novel is.”

From the front cover of The Good One: “The story of an honest police chief helplessly caught up in the seething violence and bloody fighting of a revolt in a West African colony.”

— Thanks once again to John Herrington for passing the news along to Al Hubin.

Thu 26 Jul 2007

Excerpted from an obituary in the online edition of The Guardian:

“Wing Commander Peter Cooper, who has died aged 88, spent 22 years in the RAF — including a wartime posting as air attaché at the British Embassy in Ankara – and 22 years as a Middlesex probation officer. As ‘Colin Curzon,’ he wrote two lively, witty mystery stories,

The Body in the Barrage Balloon (1942), and

The Case of the Eighteenth Ostrich (1940), and a morale booster,

Flying Wild (1941), describing the lighter side of training.

“A sometime arts correspondent for the Times, he was passionate about music, particularly that of Schubert and Wagner. As a vice-president of the Ruislip Gramophone Society he presented programmes of recorded music to rapt audiences. He was perceptive and witty in his comments on musical performances, and could be seen, always immaculately dressed, sitting on a camping stool outside London’s opera houses.”

Below is Curzon’s entry in Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J.Hubin. As you can see, not much had been known about the author until now, not even that the name he used was not his:

CURZON, COLIN. ca.1917- . With the R.A.F. during WWII.

* The Body in the Barrage Balloon; or, Who Killed the Corpse? Hurst, UK, hc, 1941. Macmillan, US, hc, 1942. Series character: Mark Antony Lennox; setting: England.

* The Case of the Eighteenth Ostrich. Hurst, hc, UK, 1943. Macmillan, US, hc, 1944. SC: Mark Antony Lennox; setting: England.

More about either of the books or Major Lennox has proven difficult to obtain:

Of Balloon, one online bookseller says only: “R.A.F. mystery.”

Of Ostrich, another bookseller says: “This is a humorous mystery story about an officer in the US Signal Corps and his disaster prone fiancee.”

Any additional information provided about the books would be welcome.

What’s a barrage balloon? That I can tell you. From wikipedia: “A barrage balloon is a large balloon tethered with metal cables, used to defend against bombardment by aircraft by damaging the aircraft on collision with the cables. Some versions carried small explosive charges that would be pulled up against the aircraft to ensure its destruction. Barrage balloons were only regularly employed against low-flying aircraft, the weight of a longer cable making them impractical for higher altitudes.”

— Thanks to John Herrington for spotting the obituary and sending the link on to Al Hubin.

Thu 26 Jul 2007

In today’s Hartford Courant, Bob Englehart’s editorial cartoon summarizes the state of the state very nicely, as usual:

On his blog, Englehart adds the following:

“As a rule, I don’t do memorial cartoons about victims of crime, but this is too much. This goes too far.

“This is an argument for an arsenal of guns in every home, a pit bull kennel in the basement of every house, armed security guards, gated communities and the death penalty. The temptation is to fight evil with evil.

“A cooler head will prevail in time, but not today. Today I vent with prose and cry with my cartoon, as does Connecticut.”

Wed 25 Jul 2007

As an introduction to this review and why I picked it out of my ‘archives,’ I recently reprinted a

review I wrote in 1979 of another in John Creasey’s long series of “Toff” books,

The Toff Among the Millions. I wasn’t entirely favorable in my comments, so when I remembered that I’d written this one not too long ago (2005), I thought what I said more recently might allay somehow what my younger self said. Whether it does or not, you may judge for yourself.

JOHN CREASEY – Double for the Toff.

Popular Library, paperback reprint; no date stated, but circa 1972. Hardcover editions: Hodder & Stoughton (UK), 1959. Walker (US), 1965. UK paperback editions: Hodder/Coronet, 1963,1973; Sphere, 1967. Earlier US paperback edition: Pyramid R-1221, Aug 1965.

I’ll make no attempt here to do a general bibliographic discussion of John Creasey and the multitude of mysteries he produced. While that will have to wait for another time, this is certainly the place. As for the Toff, in real life Richard Rollison, I don’t believe it was ever a matter of a secret identity, only an honorific nomenclature.

England seems to have had a long history of gentleman adventurers that did not seem to ever have been as popular in the United States as they were over there. The Toff, like Simon Templar, aka the Saint, before him (adventures recorded by Leslie Charteris), was merely another in a lengthy line of swashbucklers, figuratively speaking.

And again, someone else may be better to write the history of such British adventurers, although again, this is certainly the place. In fact what I know about the Toff is minimal, but of course I will tell you what I know anyway.

Let’s begin with a list of the books. These are in more or less the order in which they appeared in England. A hyphen (-) indicates the lack of an US edition. A star (*) means that there was one. A double star (**) indicates that the first US edition was a paperback. Alternate US titles are also included, if first appearances. (Thanks to Al Hubin’s Crime Fiction IV for most of this information.)

Introducing the Toff. 1938. (-)

The Toff Goes On. 1939. (-)

The Toff Steps Out. 1939. (-)

Here Comes the Toff. 1940. (*) 1967.

The Toff Breaks In. 1940. (-)

Salute the Toff. 1941. (*) 1971.

The Toff Proceeds. 1941. (*) 1968.

The Toff Goes to Market. 1942. (*) 1967.

The Toff Is Back. 1942. (*) 1974.

The Toff on the Trail. 1942. (-)

Accuse the Toff. 1943. (*) 1975.

The Toff Among the Millions. 1943. (*) 1976.

The Toff and the Curate. 1944. (*) 1969.

The Toff and the Great Illusion. 1944. (*) 1967.

Feathers for the Toff. 1945. (*) 1970.

The Toff and the Lady. 1946. (*) 1975.

Hammer the Toff. 1947. (-)

The Toff on Ice. 1947. (** – Poison for the Toff) 1965.

The Toff and Old Harry. 1948. (*) 1970.

The Toff in Town. 1948. (*) 1977.

The Toff Takes Shares. 1948. (*) 1972.

The Toff on Board. 1949. (*) 1973.

Fool the Toff. 1950. (*) 1966.

Kill the Toff. 1950. (*) 1966.

A Knife for the Toff. 1951. (**) 1964.

The Toff Goes Gay. 1951. (* – A Mask for the Toff) 1966.

Hunt the Toff. 1952. (*) 1969.

Call the Toff. 1953. (*) 1969.

Murder Out of the Past. 1953. (-)

The Toff Down Under. 1953. (*) 1969.

The Toff at Butlin’s. 1954. (*) 1976.

The Toff at the Fair. 1954. (*) 1968.

A Six for the Toff. 1955. (*) 1969.

The Toff and the Deep Blue Sea. 1955. (*) 1967.

Make-Up for the Toff. 1956. (*) 1967.

The Toff in New York. 1956. (**) 1964.

Model for the Toff. 1957. (**) 1965.

The Toff on Fire. 1957. (*) 1966.

The Toff and the Stolen Tresses. 1958. (*) 1965.

The Toff on the Farm. 1958. (*) 1964.

A Doll for the Toff. 1959. (*) 1965.

Double for the Toff. 1959. (*) 1965.

The Toff and the Runaway Bride. 1959. (*) 1964.

A Rocket for the Toff. 1960. (**) 1964.

The Toff and the Kidnapped Child. 1960. (*) 1965.

Follow the Toff. 1961. (*) 1967.

The Toff and the Teds. 1961. (* – The Toff and theToughs) 1968.

Leave It to the Toff. 1963. (**) 1964.

The Toff and the Spider. 1965. (*) 1966.

The Toff in Wax. 1966. (*) 1966.

A Bundle for the Toff. 1967. (*) 1968.

Stars for the Toff. 1968. (*) 1968.

The Toff and the Golden Boy. 1969. (*) 1969.

The Toff and the Fallen Angels. 1970. (*) 1970.

Vote for the Toff. 1971. (*) 1971.

The Toff and the Trip-Trip-Triplets. 1972. (*) 1972.

The Toff and the Terrified Taxman. 1973. (*) 1973.

The Toff and the Sleepy Cowboy. 1974. (*) 1975.

The Toff and the Crooked Copper. 1977. (-)

There was even a three-act play in which the Toff was a leading character: “The Toff.” UK, 1963.

Creasey died in 1973, so the final three books had been written and were still awaiting publication when he passed away. The Toff was popular enough in England that when his publisher (Hodder & Stoughton) ran out of Toff books to sell, they hired William Vivian Butler to write a very last one: The Toff and the Dead Man’s Finger (1978; no US publication).

Besides three books of his own, Butler also wrote the final five Commander George Gideon novels, Gideon being Creasey’s Scotland Yard detective whose adventures he wrote as J. J. Marric.

In creating this list of Toff books, there are several things I discovered that I hadn’t known before. First, I didn’t realize how many of the books were published in the US. If that were the question, the answer would be “almost all of them.” I also didn’t realize that the Toff was introduced to American readers in paperback form when Pyramid published a number of them in 1964-65, even though I purchased my copies when they did. They must have done quite well, since Walker soon took over and all of the rest of them came out in hardcover first. (Paperback editions of the Toff stories that appeared from Lancer and Popular Library were all reprints, although occasionally they altered the titles to suit editorial or marketing whims. These are not noted in the list above.)

I also suspect (but so far I have not investigated) that the early Toff books were revised and/or updated when published in this country. I understand that it was a common habit for Creasey to revise his books for whatever his current market might be, and I do not expect the Toff books to have been an exception to this general rule.

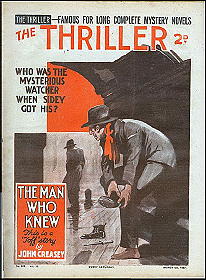

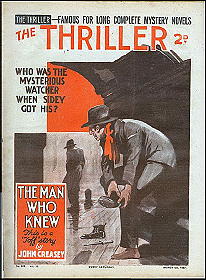

A little Googlizing on the Internet reveals that the Toff first appeared in the two-penny weekly The Thriller in 1933, so the gent with a bent for crime was really around for quite a long while. (As a useful frame of reference, the Saint first appeared in the novel Meet — The Tiger! in 1928, while several of his earliest short story cases were told in The Thriller in the years from 1929 to 1931. Simon Templar, once again, was there first, in other words.)

The issue shown is #422, March 6, 1937, and includes the Toff story “The Man Who Knew.”

On the same website as above, but on another page, is a description of the Toff’s first book-length adventure, Introducing the Toff:

“A little road rage was not unusual even in the 1940s, but the Toff was not expecting bullets to be a part of the argument when his Allard blocked the path of an oncoming Daimler in an English country lane.

“What had been a pleasant day playing cricket became the start of a lethal fight against cocaine rings, gangsters and the criminal empire of The Black Circle.

“Introducing The Toff is a typical John Creasey mystery; a ripping yarn and a fascinating document of social history as it dances between high society and the East End of London.”

This seems to have come from the back cover of a recent British paperback edition, which perhaps explains the confusion over the date, but other than that, this blurb typifies exactly what I would have imagined the Toff’s early adventures to have been like.

Returning to the book at hand, however, one can certainly read it without knowing all of the baggage that earlier stories might have brought along. One does get the sense that many of the secondary cast has been around for a while, but just as Della Street and Paul Drake were with Perry from the beginning, you can pick one of Erle Stanley Gardner’s books from the last 1960s as the first one in the series you read and not miss a beat.

Creasey does not do a lot in terms of describing Richard Rollison. I made a few notes as I went along: he’s very handsome, a head taller than average, and in admirable physical condition. That’s about it. He’s on good terms with Scotland Yard, with Superintendent Bill Grice, apparently an old friend and only a semi-antagonist, willing to give the Toff a free hand whenever he sees a reason for it.

The title comes from the fact that the Toff is handed two separate cases almost at one time, and after mulling over the possibilities, he decides he can handle both of them. Are they two separate cases? The reader knows better, but only the better reader will figure out how they are related before the Toff does.

Which is due to two factors, the first being that even though this is a pretty good detective story, Creasey is determined to tell it as if it were a thriller, with lots of action and close calls for the Toff and his friends before it is over, and doing his best to keep the reader’s eyes away from the clues. The second factor is that the time table of events is wrong, or at least, let’s put it this way. The Toff’s reactions and apparent enlightenment on page 174 do not seem to match up with his deductions. In particular, please take note of his explanation to Grice on page 187 why he did something on page 168, well before he learned what he did that put the connections together on page, yes, 174.

Inconsistencies are something you may have to learn to put up with when you read Creasey. On page 14 it is impossible to read the registration number on a motor-cycle, but on page 51 the Toff somehow knows that the motor-cycle had false number-plates. On pages 120-121 two men (bad guys) who have been gassed suddenly turn into three.

Things like these used to drive me nutty when I was younger. I try not to let them any more. The book could have (and should have) been better. But taken as a given that you have to put your mind into a lower gear when you read his tales, Creasey was certainly a grand storyteller, with (as it turns out) a kind and sentimental streak in his books (or in this one, at least) a yard wide.

Wed 25 Jul 2007

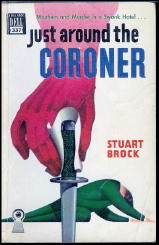

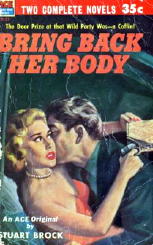

STUART BROCK – Bring Back Her Body

Ace Double D-23; paperback original; 1st printing, 1953. Published back-to-back with Passing Strange, by Richard Sale.

Stuart Brock, as all vintage paperback collectors know, especially those who collect mystery fiction also, was the pen name of Louis Trimble, who started his career writing hardcover detective novels for Phoenix Press in the early 1940s. Eventually he ended up writing westerns and science fiction novels for Donald A. Wollheim, first at Ace, then (SF only) at DAW, which would have been in the mid-1970s.

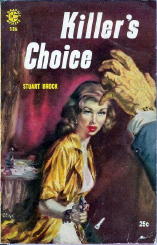

Trimble also wrote westerns as Stuart Brock, but here, taken from Allen J. Hubin’s Crime Fiction IV, is a list of all four mysteries he wrote under that name:

BROCK, STUART; pseudonym of Louis Trimble, (1917-1988)

Death Is My Lover. M. S. Mill Co., hc, 1948. Readers Choice Library #38, pb, 1952 (abridged).

Just Around the Coroner. M. S. Mill Co., hc, 1948. Dell 337, mapback, 1949.

Bring Back Her Body. Ace Double D-23, pbo, 1953.

Killer’s Choice. Graphic #136, pbo, 1956.

The detective in the latter book is a private eye named Bert Norden. I apologize to say that I don’t know who did the sleuthing in the first two books, but I’m sure that all four books are in the same deep pure pulp tradition as Bring Back Her Body, in which the detective work is done by a gent named Abel Cain. I don’t really think he ever had another case to solve, and if he did, it would be hard to imagine one more, well, remarkable than this one.

Cain’s father was, according to page 9, a renegade minister and had given his son his name as a joke, along with “a somewhat agnostic realism that Cain found to be incompatible with modern civilization.” He had been a bootlegger and a commercial fisherman, the latter which he still was when he needed the money, but mostly his time is his own, except when he acts as an unpaid, unlicensed private eye.

Which he is in this case, hired by a rich businessman to keep an eye out for his stepdaughter Paula, who has disappeared and who also just happens to have enough stock in her possession to worry her stepfather when important business deals come along, which as the book opens, will be soon.

Paula’s stepsister, Honor Ryerson, hangs out with the much older Abel Cain, and whew, is she a handful. She is an ardent believer in both astronomy and nudism, often at the same time, and is also obsessed with Cain as a would-be lover. He thinks she is a child, and she thinks not. In the course of hunting for her sister, Cain finds another woman whom he finds himself falling for, the threesome making for an odd, well, threesome, although not in the sense that may come immediately to mind.

On page 35 comes a staggering discovery, an unveiling (or unlidding, in this case) held as the climax to what you might consider a wholly decadent party: “Stretched out in the coffin, clad in a shroud, was the still, pale form of Paula Ryerson.”

As I said earlier, pure pulp, and perhaps even more risque. Well, no “perhaps” about it. It is risque to the point of edginess. There is more to the story than the last line of the previous paragraph suggests, but you will have to read the story for yourself to learn what I mean. There are certain things that I cannot begin to tell you in the context of a review without telling you too much.

Once the story begins, so does the action, and the action never lets up for the entire 142 pages of the story, which begins humorously and ends with a couple of tough, chilling scenes that are also rather shocking, mostly because … I can’t tell you.

It ends happily enough, however, as did most of the stories in the old pulp magazines. No exception here.

Tue 24 Jul 2007

Posted by Steve under

Awards[4] Comments

As you may have noticed, I’ve recently completed Author and Book profiles for the 15 total nominees in each of the three categories for the 2007 Shamus awards. The easiest way to access them is to return to the first announcement page, where I’ve created links to each of the individual profiles.

It took me longer to do this than I expected it would when I started, but I’m glad I did, because I learned quite a bit in getting it done. First of all, even though I think I keep up to date with new books as they come out, unless you spend all of your spare time in doing so, you’re bound to miss something. There are two or three books I didn’t know about before they were nominated, and I’m glad I do now.

It also seems to me, without naming individual instances, that the concept of a character being a private eye has been stretched in a few cases. I’m not the judge of such things, but in my own mind, I did question at least more than one of the nominees as being true PI novels. This is not a complaint. It’s only an observation.

The amount of violence described as being involved in again at least more than one of the nominees makes me, personally, less likely to track them down. That’s my own individual preference. I also don’t make a point of hunting down cozy novels in which deaths are treated lightly.

I’ve never been able to put into words at what point too much emphasis is put on violence in detective fiction, or when it’s too little, but believe me, I “know it when I see it.”

Over the years I’ve also grown to more than mildly not care for detective fiction in which the supernatural or the paranormal is part of the telling. For what it’s worth, which may be very little, one of the nominees may have crossed whatever line in the sand I have constructed for myself in that direction.

I wonder how many of the stories begin with a client coming into the PI’s office wanting to hire him (or her) for this, that or the other. Without going back right now to look, I’d hazard to say that it’s probably not very many, and for a couple of very good reasons. More than a couple of very good reasons, now that I think about it, but somewhere deep down inside, I sort of, just kind of, wish it weren’t so.

Please note. In none of the cases I’m vaguely referring to above am I questioning the quality of the book or books involved. I don’t see any way I could. I’ve not read any of them.

Yet.

Next Page »