Sat 31 Dec 2022

Fri 30 Dec 2022

ANNE HOCKING – Poison Is a Bitter Brew. Chief Inspector William Austen #6. Doubleday Crime Club, hardcover, 1942. Originally published in the UK as Miss Milverton (Geoffrey Bles, hardcover, 1941).

Two heirs to a fortune and a landed estate die of poison, one after the other. The first is passed off by an elderly friend of the family doctor as food poiscn1ing; the second; handled by his locum, is examined more carefully. The verdict in both: murder.

Miss Milverton, sixthy-ish proprietor of the estate until her death, is shocked. The final heir, her nephew Charles Temple, was on the scene both times and has an excellent motive, but he doesn’t act like a murderer. Chief Inspector Austen and Sergeant Pendarvis investigate.

This is a good, old-fashioned between the-wars British mystery. Why would a genteel, well-brougbt-up, upper class Englishman or woman commit murder? Not only for wealth, we find. A good read.

Thu 29 Dec 2022

PRIVATE DETECTIVE. Warner Brothers, 1939. Jane Wyman (Myrna “Jinx” Winslow), Dick Foran, Gloria Dickson, Maxie Rosenbloom, John Ridgely, Morgan Conway, John Eldredge. Based on the short story “Invitation to Murder” by Kay Krausse in Pocket Detective Magazine, May 1937. Directed by Noel M. Smith. Available for viewing online at https://archive.org/details/private-detective-1939-

In my recent review of the 1947 film Exposed, I suggested that private detective Belinda Prentice (played quite capably by Adele Mara) may have been the first female PI to have the leading role in an American movie. Not so, as David Vineyard remarked in the comment he left soon after that post appeared:

“Worth seeing Mara in anything, but I don’t think she’s the first female eye, that would be Jane Wyman as Myrna “Jynx†Winslow in 1939’s Private Detective where she works against her police boyfriend Dick Foran to solve a case.â€

True, true, true. In particular, Jinx works for the Nation-Wide Detective Agency, and the case she’s working on is that of a battle in court between a married couple over custody of their young son. When the husband is found murdered, the stakes immediately go a lot higher, with Jinx still on the case with the fellow she is engaged to marry (Dick Foran) being the police detective assigned to it.

As it turns out, the boy is the heir to a sizable fortune, and it’s no wonder that there are several suspects for the murder who are worth investigating.

The pace is quick, Jane Wyman bright, witty and appropriately sassy, and the story largely logical, with a bit of humor as well, the latter provided largely by the lovable lunk du jour Maxie Rosenblum as Foran’s assistant on the force. The story is based on a story from a detective pulp magazine, which is clearly the glue that holds everything together as well as it does, making the film one I can easily recommend. This one’s a good one.

Wed 28 Dec 2022

THE PINK JUNGLE. Universal, 1968. James Garner, Eva Renzi, George Kennedy, and Nigel Greene. Screenplay by Charles Williams, based on the novel Snake Water by Alan Williams. Directed by Delbert Mann.

James Garner plays a two-fisted fashion photographer who can flatten a man with one punch and hit two tossed cans in mid-air, shooting from the hip.

Let me repeat that: James Garner plays a two-fisted fashion photographer who can flatten a man with one punch and hit two tossed cans in mid-air, shooting from the hip.

I really should end the review right there, but since this was Charles Williams’ only filmed screenplay, and they do explain (sort of) our hero’s prowess at the end, it really deserves a bit more attention. So here it is.

For purposes of plot, Garner starts out the movie stuck in a backward South-or-Central American nation doing a photoshoot with super-model Eva Renzi. A convenient helicopter is just as conveniently stolen by lovable bad-guy George Kennedy (fresh from his Supporting Actor Oscar in Cool Hand Luke) who soon gets the couple involved in a search for a lost diamond mine.

En route to the treasure, the actors and camera crew leave the Universal backlot jungle for the arid vistas of Nevada, but they can’t shake off the hackneyed plot. They encounter another colorful rogue (Nigel Greene) and end up in a rather tame gun battle with a mousey little guy from earlier in the movie who wants all the diamonds for himself. (SPOILER ALERT!) He doesn’t get them. (END OF SPOILER ALERT!) A couple double-crosses later, it all comes to a merciful end.

Universal ground out a number of B-movies like this in the late 1960s, all seemingly put together with the same formula: A leading man past his prime, a dependable character actor, and an eye-catching actress to play carnal cat-and-mouse with the fading male lead. Stir in a modicum of action, a dollop of whatever passes for romance, and a hint of humor, let it stew among the familiar Universal studio sets and “exteriors†and….

And it worked quite well in PJ and Coogan’s Bluff. Less so — much less so — in things like The Hell with Heroes, A Lovely Way to Die, Jigsaw, and others too lame to name, by which standard, Pink Jungle is a Wheelchair Case.

To his credit, Charles Williams does what he can with it, throwing a knowing wink into the dialogue when the clichés pile up, but even he can’t get this one up on its feet. Hell, it’d take divine intervention to pull this cinematic Lazarus from its celluloid tomb, and while I can’t say for sure that angels feared to tread the Universal backlot, they never seemed to show up there in significant numbers.

I shall add that James Garner manages to grin and look light-hearted through all this, Nigel Greene projects his accustomed authority in too little screen time, and Eva Renzi, memorable in The Quiller Memorandum (or was it Funeral in Berlin? I forget which.) fills her forgettable part more than adequately.

But it’s all for naught under Daniel Mann’s leaden direction. How they kept his obvious disinterest from spreading to the rest of the cast I can’t figure — perhaps they quarantined him — but The Pink Jungle just isn’t worth that much deep thought.

Tue 27 Dec 2022

RUDOLPH FISHER – The Conjure-Man Dies. Dr. John Archer & Sgt. Perry Dark #1 (*). Covici Friede, hardcover, 1932. Reprinted several times, including: Arno Press, hardcover, 1971, introduction by Stanley Ellin. University of Michigan Press, softcover, 1992; Poisoned Pen Press, softcover, 2022.

The first Black detective novel. It is set in Harlem, involving the murder of a soothsayer.

The author was a doctor who died by cancer aged 37. By proxy, he places a Dr. Archer, who lives across the street from the crime scene. Archer volunteers his scientific services to the aid of Detective Dart of the Harlem precinct. Local politicos made the recent choice to hire Black police officers, as better able to traverse Harlem’s cultural eccentricities.

An excellent introduction by Stanley Ellin points out the interesting combination here of Van Dine inspired scaffolding, scientific induction and overlong exposition with Hammett-like precision in dialogue.

What makes the book unique is its presentation of Harlem characters in their colorful vernacular of the times — a vernacular whose stark presentation may be inspired by Hammett but the content of which is entirely its own.

Enjoyable mystery and worth reading even were it not an important historical document.

(*) The pair of detectives also appeared in the novella “John Archer’s Nose,” which was collected in The City of Refuge: The Collected Stories of Rudolph Fisher (University of Missouri, 1987). This may have been its first appearance.

Mon 26 Dec 2022

JOHN CREASEY – A Knife for the Toff. Richard Rollinson #24. Evans, UK, hardcover, 1951. Pyramid R-1097, paperback, 1st US edn, 1964.

Richard Rollinson, the Toff is on the dance floor with the beautiful Camilla aboard a yacht owned by the ruthless and grossly fat Rumplemeyer who watches malevolently over them, and despite the seeming atmosphere of gaiety time is running out for the Toff as he flirts with his beautiful dancing partner.

“Yes…The facade of beauty and the interior decoration of corruption. What turned you from a sweet innocent child into a worshiper before the shrine of that maggoty Buddha? Was it just that gold glitters? Were your tiny feet turned off the straight and narrow path by the lure of the luscious life, or did some great tragedy blight your whole existence?â€

That, of course, is the authentic voice of the gentleman adventurer of the Twenties and Thirties however hardened and changed by the War. But the day of the swashbuckling poetry-spouting hero serenading bobbies in the street and speeding down narrow foggy roads in low slung cars is over. Tough guy Americans, Peter Cheyney, and the War ended all that and James Bond is about to put the boot in it for higher stakes than boodle.

It is 1951, and the breed has changed a bit, grown a shade tougher, and less concerned with the niceties. We are still two years out from James Bond, but at times it is hard not to wonder that the same things that influenced Ian Fleming’s licensed public executioner might not be haunting the Toff as well. He’s not quite the same man he was before the War.

The Toff was always the odd man out of the gentleman adventurer school. Not only was he genuinely from money and birth (“A gold spoon,†he tells Camilla when she accuses him of having been born with a silver spoon in his mouth). Despite that his knight errantry came with a social conscience, it is hard to imagine Simon Templar or Norman Conquest possessing, and however close he skirts it, he is never a desperado or outlaw, just a bit careless with the workings of the law when they interfere with justice.

Even in those rare cases where the villain he’s pursuing is a personal one (The Toff Goes to Market, in which Aunt Gloria is poisoned by wartime black marketeers), he’s far less likely to fling himself through plate glass windows with guns blazing or dangle the odd bad guy out windows than the Saint or 1066, and unlike Creasey’s other gentleman hero, the Baron, he would never take revenge on a social order that betrayed him.

It’s hard to imagine the Saint financing a club for boys in the East End like the Toff.

All that is about to go out the window with this one though. It is 1951, a new decade, and Rollinson is up against a different kind of bad guy than the usual petty master criminals he’s used to, and the fantastic Rumplemeyer has Rolly trapped on his yacht, the Lucretia, with only minutes to choose between a watery grave and serving a hideous criminal master.

While Creasey always opens well, it is unusual for him to put the Toff in the thick of it on page one and start ratcheting from that point on.

What Creasey excels at is the choreography of tension and action. His heroes are not the kind to stand around wondering what course to take. That’s another Bondian tie. They aren’t afraid to kick the card table over when they get a bad hand.

The Toff does escape, with the help of Camilla, who has fallen for him and reformed based on nothing but a kiss (shades of Pussy Galore, and there is more than one parallel here between Fleming and Creasey with a few bits similar to scenes in Diamonds Are Forever and Goldfinger), with both of them escaping on a lifeboat only to end up stranded at sea for ten days while they fall in love.

Meanwhile back at the farm the Toff’s man Jolly (like Tonto the brains of the outfit despite his comic relief role), his wealthy disapproving titled Aunt Gloria, East End boxer and pub owner Bill Ebbutt, and Rolly’s rival/friend Grice of the Yard believe him dead, which if nothing else gives us a chance to take a tour of the Toff’s trophy wall (the finest such museum outside the Yard’s Black Museum) replete with a top hat with a bullet hole in it, various knives, poisons, coshes, and a hangman’s rope that was used on one of the more unlucky types the Toff battled

Rollinson and Camilla are rescued, but when the get back to London, before they can even get off the ship, an attempt is made on their lives and Camilla receives a serious head wound thanks to Rumplemeyer’s man in the UK, the Wizard, who the Toff believes is one Colonel Merlin.

In almost every book the Toff finds himself at odds with the police, even hunted and forced to work alone, or with his unlikely allies in the East End, to defeat the threat at hand, but here it is with a vengeance. Always before the Toff was a justice figure, but the least bloodthirsty of the type.

Not here. He’s not defending the idea of justice, this time it is personal and he’s ruthless.

Granted he doesn’t go around popping off the unwashed with the vigor of the Saint or Norman Conquest, but he leaves a few bodies behind before he uncovers Rumplemeyer’s plot to use an illegally acquired submarine to hold up a shipment of gold bullion at sea (shades of Goldfinger and Assault on a Queen), ending with the Toff aboard a Royal Naval destroyer hunting down Rumplemeyer for a savage finish.

But that isn’t the end, the end is a bittersweet note with a bit of class conscious reality thrown in the mix, and here is where Creasey and Fleming really part ways, because by the last line the old irrepressible Toff is back, a bit heart sore and sadder but wiser. No year long benders getting out of shape and agonizing over his life choices for the Toff.

It’s not that he’s made of sterner stuff. Only that he is cut from thinner cardboard, and Fleming’s war was much dirtier than Creasey’s.

This is my favorite among the Toff novels, actually the second one I read at the easily influenced age of fifteen (the first was The Toff in New York), and part of what sold me was a great Jack Thurston cover with a top-hatted Toff in the upper left corner, cigarette holder in hand, while on the cover the Toff and Camilla stand on the deck of something (hard to say what) as fireworks go off on the deck of a surfaced submarine behind them.

I’m fairly sure that cover would have sold me any book, whether I had ever heard of Creasey or not (and no, that scene isn’t in the book).

I reread the book for this review with only a shade less enjoyment than when I first read it. While it has many of Creasey’s problems as a writer it also has all of his virtues, which for me outnumber the former, and today has the added cachet of how much it has in common with some of the Bond’s to come and the changing tone of the Post-War British thriller.

No, I don’t think Fleming read Creasey, though it is possible, but I do think both men were reflecting something new to popular fiction in that time period that came out of the War each in their own way, and to be perfectly fair, the Toff being on that destroyer doesn’t make any more sense than Bond manning a Bofors gun in South Africa at the end of Diamonds are Forever, but I’m grateful to Creasey and Fleming for not caring and doing it anyway. (*)

(*) And I was grateful when Philip McCutchan’s Commander Esmonde Shaw and James Dark’s Mark Hood finished with similar scenes in their adventures. I like my fictional t’s crossed and i’s dotted, whether it makes sense or not.

Sun 25 Dec 2022

Sat 24 Dec 2022

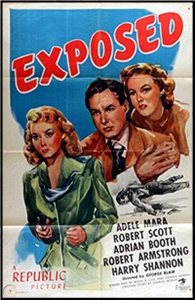

EXPOSED. Republic Pictures, 1947. Adele Mara (Belinda Prentice), Robert Scott, Lorna Gray, Adrian Booth, Robert Armstrong, William Haade, Bob Steele, Harry Shannon. Director: George Blair.

It’s possible, depending on definitions, that this is the first movie in which a female private eye is the leading character. You may be thinking right away about Torchy Blane and the movies she was in, and I wouldn’t blame you, but she was a newspaper reporter with a good eye for crimes and who committed them, but no, she wasn’t a PI.

Adele Mara is the PI in this one, a brash young lady named Belinda Prentice, but while she tries hard, she doesn’t have the patter that a good wisecracking PI needs in the movies (blame the writers). Not only that, but the fact that she needs a lovable lunk of an assistant named Iggy (William Haade) to get her out of scrapes is another strike against her.

Noting that her father is the chief of homicide (played to perfection by Robert Armstrong), we can only agree that as an independent operator, Miss Prentice is pretty much a minor leaguer.

It doesn’t help that the case she’s hired to work on (that of a father wanting to know why his son is taking so much money out of their firm’s account) is so muddled, even when it turns into a case of murder as so many cases such as this invariably do. Watch this and see if I’m not right. Muddled. And even so, there are too many scenes of people walking from one place to another, as well as automobiles driving in or off somewhere, as if they were a new invention.

One scene does stand out, though, that of Iggy and Bob Steele’s character (a hood by the name of Chicago) having a smack ’em up, knock ’em down fight that’s well worth the price of admission (free on YouTube).

Fri 23 Dec 2022

Q. PATRICK – Death Goes to School. Smith & Haas, hardcover, 1936. Banner Mysteries #2, digest-sized paperback, April 1945.

Anthony Boucher once mentioned in a letter to John Dickson Carr that it was the authors using the pseudonyms of Q. Patrick, Patrick Quentin, and Jonathan Stagge, who developed a certain gimmick in mystery writing: their books during the 193Os challenge the reader to discover not only who is the murderer but also who is the detective.

Often, but not always, the narrator is the detective; sometimes the police detective discovers the criminal; occasionally the amateur detective actually, turns out to be the murderer. Even a relatively minor Q. Patrick work like Death Goes to School plays with the reader, and not till the end do we discover who solves the crime.

The story takes place in an English boarding-school, two of whose students are murdered apparently because their father, an American judge, has passed sentences against some Nazis. I describe the story as minor because the focus is not always clear and because the surprise ending can be predicted by readers who know Patrick’s tricks.

But there is much to praise in it, especially the character of St. John Lucas, a schoolboy who (having read Chums and other sensational papers for adolescents) helps unearth evidence. But I like Patrick/Quentin/Stagge so much that even when I can see through their tricks I enjoy their work. Indeed, I am beginning to revel in predicting their gimmicks.

In short, I recommend Death Goes to School for those who haven’t read enough Patrick to predict the solution, and for those who have reached the point that they positively enjoy outguessing the author.

Thu 22 Dec 2022

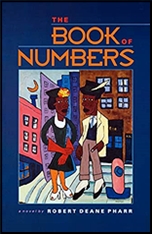

ROBERT DEANE PHARR – The Book of Numbers. Doubleday, hardcover, 1969. University of Virginia Press, softcover, 2001.

Dave Greene and Blueboy are Black travelling waiters in the 1930’s, going from resort town to town with the seasons: Saratoga, Hot Springs, wherever the white leisure class goes, you’re sure to find them there. Waiting.

And since segregation is still a thing, there’s a Black ward in every one of these towns. With Black whore houses, bars and gambling to match so that these travelling waiters can spend every cent they earn. All except for Dave Greene. He’s got bigger plans.

Dave’s father was a ‘lawyer’: ‘Lawyer Greene’. He wasn’t a real lawyer — never having gone to law school, never having passed the bar. But he knew more about the law than most of his peers, and he knew enough to represent his clients by genuflecting like a bending slave, ‘yessah’-ing and ‘nossah’-ing and bowing to whitey begging forgiveness and promising to do better from now on.

Dave grew up thinking his dad was an actual lawyer entitled to respect. It was only when he grew older and began to understand that other Black folks in the community viewed ‘Lawyer Greene’ as a pathetic minstrel that Dave began to hate his father and crave actual and deserved respect.

So rather than spending all his travelling waiter money on prostitution, alcohol and craps, Dave saves up. For something. He’s not quite sure what.

But then he and Blueboy wind up in Richmond, VA. And they notice something strange. There’s no local numbers racket. All the locals play numbers by sending money to Detroit or Chicago or some other big town. But there’s nowhere local to play.

The way you play numbers is you pick any number from 000 to 999. And you can bet any amount you want, starting with a penny. And if your number ‘hits’, you win on 600-1 odds. So a penny bet will get you six dollars. And so on.

Dave has saved up $1000. And he’s sick of playing minstrel to whitey. He’s ready for some respect. So he and Blueboy quit being waiters and start a numbers racket in Richmond’s Black ward.

They make it big. Really big. And end up millionaires. In cash. But they aren’t really allowed to spend it any way they want. They try to go legit. To invest in a franchise of some kind. Or a dealership. But Blacks aren’t allowed to own a franchise or dealership in nearly every industry of the time.

And white politicians and law enforcement start expecting bigger and bigger payoffs. And violence in the ward is a thing. A thing you can’t avoid. No matter how big you think you are. Sudden death is never far behind.

It’s a good novel. Didn’t blow me away. But it’s good. And does an excellent (what do I know?) job of showing you what life was like for local numbers bosses in the segregated south of the 30’s. Pharr’s own biography is similar to that of his protagonists — and his actual experiences surely inform the verisimilitude of the story told. The vernacular of the dialogue is fresh and frequently hilarious, with such lines as: ‘he’s too short to kick a duck’s butt’ and ‘don’t look a gift whore in the mouth.’

In an interview Pharr says his goal was to be a Black Sinclair Lewis. He was inspired by Babbitt and getting a glimpse inside the upper middle class white home, to see what life was like behind closed doors, doors heretofore forbidden. Now opened wide. Pharr wished to do the same for Black culture. To let you see what Black folks are like when whites aren’t looking.

The characters are all three-dimensionally drawn, with romance and dreams and heartbreak. While the main characters may be nominally gangsters — they bristle at the accusation. They don’t see themselves that way. They just see themselves as men, and they dream to be treated as such.

Made into a film of the same name in 1973. . Currently online at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hQJAanxjgcQ.