Thu 28 Jan 2021

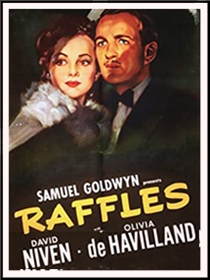

A Movie Review by David Friend: RAFFLES (1939).

Posted by Steve under Mystery plays , Reviews[14] Comments

RAFFLES. United Artists, 1939. David Niven (Raffles), Olivia de Havilland, Dame May Whitty, Dudley Digges, Douglas Walton (Bunny), E. E. Clive. Based upon the celebrated adventures of “The Amateur Cracksman” by E. W. Hornung. Directors: Sam Wood and William Wyler (the latter uncredited).

A gentleman jewel thief who routinely baffles Scotland Yard decides to retire. This is because the thief – really A.J. Raffles, famous cricketer – has fallen in love with a girl called Gwen and has vowed to end his career of safe-cracking. However, when his friend Bunny is unable to pay off his debts, Raffles decides to help by stealing Lady Melrose’s necklace. He manages to wangle an invitation to a weekend party she is hosting at her estate and anticipates an easy success. However, Inspector McKenzie attends the party to prevent the theft and another burglary is set to go down the same night…

Today, we’re in an era of Hollywood studios remaking films which aren’t yet twenty years old. Well, this one certainly kicks them to the curb. This is a remake of a nine-year old film from the same country, same studio, same director and same script. And, as David Niven replaces Ronald Colman, it could even have the same moustache too. But, this isn’t a criticism. For one thing, in 1939, they didn’t have DVDs (imagine!), so it had been nearly a decade since people had seen the first film. Also, this has David Niven. Also, this has David Niven. Also, this has … well, it does.

Niven was born to play the role, and it’s a shame that he didn’t make a bigger splash with it. This could easily have been a series, like the Universal set of Sherlock Holmes films with Basil Rathbone. Of course, the war happened and Niven, quite honourably, left Hollywood to fight. And maybe the idea would have been redundant, as this was the same year in which the Saint movies started.

With his easy charm and suavity, Niven is the best thing about this version. The plot is solid and – though set in a house for most of its run-time – features much of the cosily exciting wandering-around-the-house-at-night stuff that I love so much. It heads towards farce, at points, but you won’t read me complaining about that, as it’s all so lightly amusing and even quickens the pulse at times.

Dame May Whitty (she of The Lady Vanishes – surely one of the best films in the history of moving pictures) plays the dowager-type part of Lady Melrose and there’s some mild comedy to be enjoyed with her oafish aristocratic husband who is straight out of a Blandings novel.

The whole thing about giving Raffles a love-interest is non-canonical, as that never happened in the original stories by E.W. Hornung (brother-in-law of Arthur Conan Doyle). In fact, Raffles himself is softer here than he is supposed to be and Bunny’s suicide pledge is only alluded to, while it was properly depicted in the story which inspired it.

At this point, the character had enjoyed a renaissance of sorts in the British pulp magazine The Thriller, with stories written by Barry Perowne, in which the character was updated to the ’30s. This film is also set in those times (though, confusingly, there’s a scene in a Victorian hansom cab) and there’s even a television, before the invention was really popular.

Unfortunately, this spirited film is marred by a hasty ending which, jarringly, tries to include a daring escape, a Golden Age of Hollywood romantic ending and the obligatory reminder that crime does not pay.

The character would again find success in a 1977 television series for ITV with Anthony Valentine in the role. A one-off adaptation, titled The Gentleman Thief, was aired in 2001 and starred Nigel Havers. It was a role he was surely also born to play but, unfortunately, was not followed up on, and hasn’t even had a DVD release. Considering the original books are still in print and remain classics of the genre, it would be great to see them adapted again at some point.

Rating: ***