June 2009

Monthly Archive

Tue 30 Jun 2009

IT’S ABOUT CRIME

by Marvin Lachman

I suspect that detectives like Henry Tibbett [whose mystery case Falling Star, by Patricia Moyes, was reviewed here several days ago] were a reaction to the eccentric sleuths of an earlier era, e.g., Holmes, Wolfe, and Poirot.

Mystery writer John Creasey fathered a small army of detectives, all of whom had “smarts” and physical prowess, though none were especially colorful. Understandably, but perhaps unfairly, Creasey’s name has often made mystery readers smile. The most prolific mystery writer, he started by writing some dreadful books in his early days.

Nor were all of them mysteries, since he wrote in all genres. (One of his early “Tex Reilly” westerns is reputed to contain the deathless line about coyotes flying in the sky.)

Creasey was best known for his Commander George Gideon books, written under the J.J. Marric pseudonym, but G.G.’s roots were clearly in his older literary brother, Inspector Roger “Handsome” West, who appeared in forty-three novels and at least one short story.

West started off rather inconspicuously in 1942, depending on a socialite friend for much of his detection and legwork. However, as the series progressed, Creasey’s writing and West, as a hero, improved.

Happily, Harper’s Perennial Library has recently reprinted eight of the Roger West series, and their selection is excellent, as witnessed by the following examples.

Serial killers are everywhere today. (I’m sure I pass them on the streets as I walk from the train to work.) The Beauty Queen Killer (1954) is a good early example, with some exciting scenes, marred only by difficult to accept motivation.

The Gelignite Gang (1955) dates from the same year as the first Marric novel, and it also gives a good picture of London from a policeman’s viewpoint.

Here, the police are faced with a series of jewelry robberies, with the titular form of dynamite the common factor. When murder occurs during robbery in the city’s largest department store, West is called in to solve a mystery that has more surprises than most.

In Death of a Postman (1956) Creasey accomplishes what relatively few mystery writers do: he makes us care about the victim. A postal worker, who leaves behind a wife and five children, has been murdered during the Christmas rush. As we rapidly turn the pages of one of Creasey’s best narratives, we become involved and want West to track down a particularly heinous killer.

– From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 10, No. 3, Summer 1988 (slightly revised).

Bibliographic details:

The Beauty Queen Killer. Harper & Brothers, US, hardcover, 1956. First published in the UK as A Beauty for Inspector West, Hodder & Stoughton, hc, 1954. US paperback editions include: Dell 985, 1957, as So Young, So Cold, So Fair. Berkley F1095, 1965; Lancer 74757, 1971; and Perennial, 1987.

The Gelignite Gang. Harper & Brothers, US, hardcover, 1956. First published in the UK as Inspector West Makes Haste, Hodder & Stoughton, 1955. US paperback editions include: Bantam 1884, 1959; Berkley F1176, 1966, as Night of the Watchman; Lancer, 1971, as Murder Makes Haste; and Perennial, 1987.

Death of a Postman. Harper & Brothers, US, hardcover, 1957. First published in the UK as Parcels for Inspector West, Hodder & Stoughton, 1956. US paperback editions include: Bantam 1883, 1956; Berkley F1167, 1965; and Perennial, 1987.

Tue 30 Jun 2009

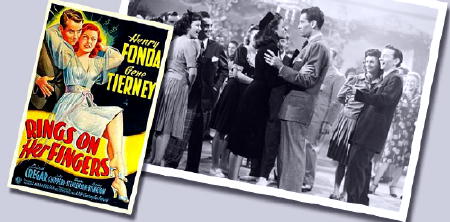

RINGS ON HER FINGERS. 20th Century-Fox, 1942. Gene Tierney, Henry Fonda, Laird Cregar, Spring Byington, John Shepperd (Shepperd Strudwick), Frank Orth, Henry Stephenson. Director: Rouben Mamoulian.

Gene Tierney was as beautiful an actress as Hollywood ever produced, wasn’t she?

In the scene in this mostly light-hearted movie in which she’s trying to attract Henry Fonda’s attention, dressed in a single piece bathing suit and stretched out on a blanket along the shore, he’s so distracted he can hardly talk, and who can blame him?

Over the span of her career, Gene Tierney didn’t do too many romantic comedies – most of her films seems to be straight dramas (Dragonwyck, The Razor’s Edge) or crime films with a strong noirish flavor (Laura, of course, and Night and the City) – but she acquits herself well in Rings on Her Fingers, making me wish she’d done more movies in the same vein.

Looking through her list of films, I see only That Wonderful Urge (1948), a remake of Love Is News (1937), with Tyrone Power in both, as a movie that’s in any sense comparable to Rings on Her Fingers.

In a way, you might call this film a “re-imagining” of The Lady Eve (1941), in which Henry Fonda played against Barbara Stanwyck. The gimmick here is that Henry Fonda’s character is poor, not rich, and when Gene Tierney’s character is part of a flim-flam which fleeces him of $15,000 hard-earned dollars, it’s easy to see that the two of them will get together, but how will she keep her part of the swindle a secret from him?

Not that she’s a bad girl, only a shop girl easily tempted by glamor and easy riches, and taken in by the real pair of crooks, Laird Cregar and (believe it or not) Spring Byington. And what a mis-matched pair they are: Cregar was a giant of a man in size (but nimble enough on his feet), and Byington was tiny and nearly swallowed up on the screen in comparison.

Is this a screwball comedy? I’ve asked myself that, and when I did, I didn’t get an immediate response, mostly because, like “noir film,” I don’t know that I have an exact definition of screwball comedy in mind.

But I guess I know one when I see one, and at the moment I’m inclined to say No as far as Rings on Her Fingers is concerned. The romantic problems are a little too real, with too much of an edge to them (how does she keep him finding out that she was part of the con game that took him in?), and there doesn’t seem to be the kind of goofy wackiness that I associate with other screwball comedies of the 1940s.

As for Henry Fonda, he’s perfect for the part, naive but noble, and what a way to make a living: kissing Gene Tierney.

Mon 29 Jun 2009

JUDSON PHILIPS – A Murder Arranged. Dodd Mead, hardcover, 1978. Reprint hardcover: Detective Book Club, 3-in-1 edition, November 1978. No US paperback edition. (Shown is the cover of an Italian softcover edition.)

Journalist Peter Styles’ crusade against senseless violence leads him to an out-of-the-way New England village where he becomes the champion of a young man accused and convicted of murder. All the evidence seems to point directly to Tim Ryan, but the feeling of at least half the townspeople is that the state police wrapped up their case far too quickly.

Obviously there’s more than a little resemblance here to a story that recently made Connecticut headlines, and the reader is swallowed up at once into the affairs of a small town. In spite of some fast deductions and the long arm of coincidence in the final chapters, Philips demonstrates once again that few authors are so non-stop reliable as he.

— From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 3, No. 3, May-June 1979

(very slightly revised).

[UPDATE] 06-29-09. For an author as popular as Judson Philips (1903-1989) was, it never made sense to me that a good percentage of his books never came out in paperback. Including the books he wrote as Hugh Pentecost, his hardcover mystery fiction would have filled at least two long shelves at your local library.

Philips began his career writing an even longer list of stories for the pulp magazines in the 1930s, and books continued to come from his typewriter very nearly up to the day he died. A list of his book-length fiction can be found online here.

If it weren’t for readers and collectors of pulp magazines, I imagine that Philips would have fallen long ago into that ever-growing limbo of mystery writers who sold tons of books in their day, but who are fast fading from memory today. (A list of his “Part Avenue Hunt Club” stories from Detective Fiction Weekly that have recently been reprinted in a two-volume set from Battered Silicon Dispatch Box can be found online here.)

Mon 29 Jun 2009

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

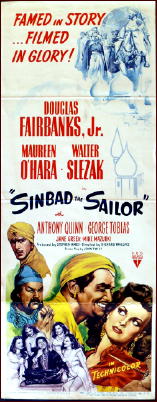

SINBAD THE SAILOR. RKO, 1947. Douglas Fairbanks Jr., Maureen O’Hara, Walter Slezak, Anthony Quinn. George Tobias, Jane Greer, Mike Mazurki, Sheldon Leonard. Co-storywriters: John Twist & George Worthing Yates; director: Richard Wallace.

Moving on to swashbuckler movies from westerns, a while ago TCM did a series of “Sinbad” flicks which finally floated to the top of my to-be-watched pile.

Sinbad the Sailor is a lush 40s Technicolor extravaganza with odd touches of noir as an equivocating Douglas Fairbanks Jr. moves into uneasy alliance with an enigmatic Maureen O’Hara, and they both play cat-and-mouse with hard-boiled icons like Anthony Quinn, Walter Slezak, Jane Greer and even Mike Mazurki and Sheldon Leonard, all looking a bit out of place in Arabian Nights country, but giving it a shot anyway.

The stunt work is nothing to write books about (disappointing from a swashbuckler of Fairbanks’ pedigree) but the sheer, ebullient silliness of the thing carries it off.

Coming soon:

Dan’s reviews of Son of Sinbad (1955) and Captain Sinbad (1963). In the meantime, I wish I’d found a copy of this photo in color:

Mon 29 Jun 2009

TED ALLBEURY – The Reaper.

Grafton; UK paperback original, 1st printing, 1980. US title: The Stalking Angel. Mysterious Press, hc, 1988; Warner, pb, 1989.

I recently purchased a small collection of spy thrillers written by Ted Allbeury, some British editions, some published in this country. (When this book appeared over here, the title was changed to The Stalking Angel, a modification all to the better, to my way of thinking.)

And not having read anything by the author before now, I picked this one more or less at random. This is in violation of a general principle promulgated by an esteemed colleague of mine, which I usually adhere to, which is to never read a book with a swastika on the cover.

Without getting into the details of the plot, at least not yet, what I discovered was what the book by John Jakes I recently reviewed was missing. Often times you can describe what you see. It’s what’s not there that’s sometimes difficult to put your finger on. Jakes’ book was written strictly in black and white, which I pointed out, although I was referring to films at the time.

Allbeury’s book has the in-between gray that better spy novels seem to thrive on. The moral dilemmas, the idea that “you always pay.” From page 136, former CIA agent Hank Wallace is warning Anna Simon, his protégé with whom he has fallen in love:

“You pay a price when you kill someone. It’s a different price for different people. It doesn’t matter if the killing is just or unjust, you still pay the price. You don’t necessarily pay immediately; it may be years later when you have almost forgotten what happened. But you pay. And you always seem to pay when you can least afford it.”

A group of aging ex-Nazis, tired of being hunted down and killed, has decided to retaliate, and Anna’s husband, working (unknown to her) for a Jewish organization tracking them down, is one of their first victims.

As the US title then suggests, Anna then begins to take revenge in her own hands. You might think you know exactly where this will lead, and it probably does, but (more than likely) not exactly on the path you think it will.

Being judge, jury and executioner all in one — it’s not the easiest job in the world, and Allbeury does a better than average job of showing us why.

Biographic data:

Ted Allbeury died 4 December 2005. A long obituary I’ve found online contains a wealth of information about him, from which I’ve excerpted the following:

“Ted Allbeury, who has died aged 88, was the most productive of the internationally recognised spy writers of recent years, at one point writing four novels in one year under his own name, plus others under the pen names Richard Butler and Patrick Kelly. […]

“The author of more than 40 novels and numerous radio plays, Ted came to writing late in life (he was 56 when his first book, A Choice of Enemies, appeared in 1973). […]

“A tall, imposing man, with an alert mind and an ease with languages, he served as an SOE intelligence officer from 1940 to 1947, rising to the rank of lieutenant colonel. […]

“Ted’s work was not so much a reaction to other spy fiction writers, but an extension of the work that Deighton and others had begun: first, he wanted to deepen the wartime thriller; and second, he aimed to make unusual common cause with enemy agents as human beings, thus exposing the power relations on both sides as his real target.

Even if you have only a small interest in the British spy novel, the rest of the obituary is well worth your reading.

Mon 29 Jun 2009

REVIEWED BY WALTER ALBERT:

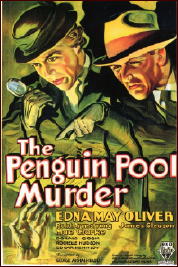

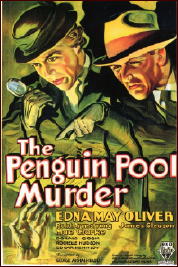

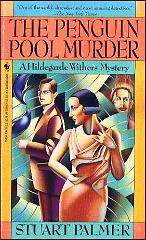

THE PENGUIN POOL MURDER. RKO Radio, 1932. Edna May Oliver, James Gleason, Robert Armstrong, Mae Clarke, Donald Cook, Edgar Kennedy. Based on the mystery novel by Stuart Palmer. Director: George Archainbaud. Shown at Cinevent 19, Columbus OH, May 1987.

The Penguin Pool Murder is based on the popular Stuart Palmer Hildegarde Withers series and was the first of three films to star the redoubtable Edna Mae Oliver as the spinster amateur detective.

I thought it a very appealing film indeed, but when I mentioned my enjoyment of the film to a friend he observed that he had erased it from a tape, expunging this “poorly paced” Withers/ Piper collaboration, but preserving for posterity (and me, perhaps, at a later date) a “superior” later entry in the series.

I liked the film for the fizzy chemistry between Edna Mae Oliver and Inspector Piper, played with his usual engaging asperity by James Gleason, and what seemed to my bemused eyes to be a nicely paced comedy-mystery with some Oscar-worthy histrionics by a talented penguin.

But I must confess that when it comes to Edna Mae Oliver, I am a patsy in the throes of an unrequited passion. My favorite Oliver performance is in John Ford’s Drums Along the Mohawk, where she plays a feisty widow putting Indians to rout with a broom and a stentorian voice until an arrow terminates her terroristic cavorting.

(The only contemporary actress I can compare her to in the effect she has on me is pint-sized Linda Hunt, who conveys more intelligence and sympathy with a look than most actresses do with a pageful of dialogue. I enjoyed her unanchored — by the script — performance in Silverado, where amid the clutter of this entertaining shoot-’em-up [and down], she displays a purity of character and demeanor that raises most of her scenes to a level to which little else in the film aspires.)

As for Penguin Pool Murder, however, I will delay my definitive judgment on it until I have seen the other Oliver/Gleason collaborations in the series.

– Reprinted from The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 9, No. 3, May/June 1987 (very slightly revised).

Sun 28 Jun 2009

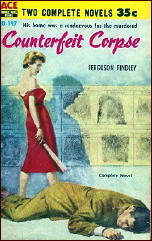

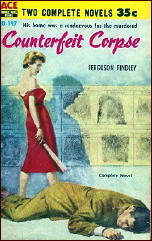

FERGUSON FINDLEY – Counterfeit Corpse.

Ace Double D-187, paperback original; 1st printing, 1956.

Findley wrote a small handful of crime novels back in the 1950s, and I’ll add a list of them at the end of my comments on this one, which I enjoyed, but which I’d be hard pressed to recommend to anyone else without waving a lot of warning flags first. (Read on.)

A fellow named Don Ivy is the featured player in Counterfeit Corpse, and he tells the story himself. After being bounced out of England, after years of knocking around Europe and northern Africa during and after the war, and now that his mother’s dead, he’s settled down in the small town in New England and living in the very same house he grew up in.

It’s not clear whether the town of Tombury is supposed to be in Vermont or New Hampshire, but since later on in the story he and his niece Judy have to cross the Massachusetts line while making a quick trip to Boston, my vote’s for the latter.

Which of course doesn’t matter to you. What does matter, I think, is that the reason he was quietly kicked out of England was his expertise in making counterfeit plates (for ten pound notes) so well that the bills they were capable of printing could not be distinguished from real ones, save for one small deliberate flaw that only Ivy knows.

He has no record in England, though — it’s been erased, thanks to services to the Crown. Which is all prelude to the story, though, which begins with Ivy finding a body in his yard while doing a spring cleanup. Then another – a roadside accident — then his niece Judy, whom he hasn’t seen in maybe 15 years, shows up; and then another body is found face down in a pond behind his house.

Coincidence? Not on your life. It certainly gets the local authorities into an uproar, though. First the local cop, then a state policeman, then a guy from the FBI. It’s up to Ivy and the surprisingly capable assistance of his niece Judy to get him out of trouble before he’s up to and over his neck in it.

Breezily told, in good old-fashioned pulp magazine style, the tale has some flaws I ought to tell you about, too. The pile up of bodies is no coincidence, but heading to Boston to look for clues, it strikes me as next to impossible that he find the correct cheap night spot where all of the players in the plot struck out from, in only one try — and how did they all come to be there in one spot to begin with? That’s neatly not mentioned or alluded to either.

There is not a lot of detective work going on in this book, not the real deductive kind, that is, until the end, in which (unless I’ve read it wrong) Ivy doesn’t recognize a certain telephone number, one that he should know, until several hours later, when it is almost too late.

What is amusing, I think, is how Ivy manages to steal the local cop’s girl friend away from him, after the local cop, trying to be friendly, uses the girl friend as part of his cover in the aforesaid enterprise.

And if you’ve read this far, you might as well read the book and see how he does it, whether it ‘s a good move or not; or on the other hand, you might decide that I’ve told you enough of the story already, and that anything more would be superfluous.

Bibliographic data: [Expanded from the Revised Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin; US editions only.]

FINDLEY, FERGUSON. Pseudonym of Charles Weiser Frey, 1910-1963.

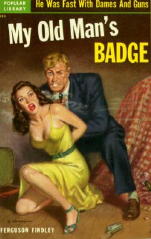

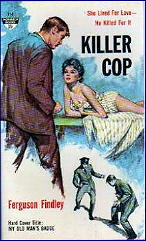

My Old Man’s Badge. Duell, 1950 [Johnny Malone]. Popular Library #324, pb, 1951. Also reprinted as Killer Cop (Monarch #114, pb, 1959).

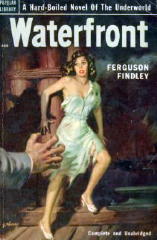

Waterfront. Duell, 1951 [Johnny Malone]. Serialized in Collier’s Magazine, August 1950. Popular Library #408, pb, 1952.

The Man in the Middle. Duell, 1952. Reprinted as Dead Ringer (Bestseller B160, 1953).

Counterfeit Corpse. Ace Double D-197, 1956.

Murder Makes Me Mad. Popular Library #780, 1956.

Sun 28 Jun 2009

A MOVIE REVIEW BY DAVID L. VINEYARD:

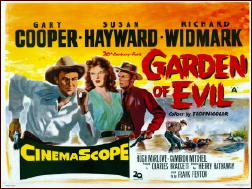

GARDEN OF EVIL. 20th Century-Fox, 1954. Gary Cooper, Susan Hayward, Richard Widmark, Cameron Mitchell, Hugh Marlowe, Rita Moreno. Screenplay: Frank Fenton; director: Henry Hathaway.

“If the earth was made of gold, men would still die for a handful of dirt.”

When is a western not a western?

When it’s an adventure film, like The Treasure of Sierra Madre and this, Henry Hathaway’s Garden of Evil, even though it is set in the classical western period after the Civil War and features gunmen and Apaches.

Gary Cooper, a soldier; Richard Widmark, a gambler; and Cameron Mitchell a gunfighter too fast with a gun and his temper are aboard a ship headed south when they arrive too late in a small Mexican fishing town to make their ship and have weeks to wait until the next ship is due.

We never learn exactly what they are fleeing, but it is clear from the subtext of the film that what they are seeking — each in their own way — is a new beginning, redemption. None of them expect to find it in this sleepy little fishing village where the most excitement would seem to come from a flirtatious girl (Moreno) in the cantina, and a jealous vaquero.

But today is the day Susan Hayward shows up, a desperate American who says her prospector husband has been trapped in a mine and she needs help to save him — help she will pay for. But there are no takers. Hayward and her husband have been prospecting an old Spanish conquistador mine, one in the interior in a remote valley guarded by an almost stone age band of Apaches. No local will follow her for any amount of money. The valley is haunted, and damned.

But Cooper, Widmark, and Mitchell will, and the vaquero. They can be bought for money, the lure of gold, and the beauty of a woman. They are men who hold those things more dearly than life.

The tension rises as they set out toward the valley. The vaquero is trying to mark the trail (not knowing Hayward has destroyed his markers), and Cooper has to beat Mitchell half to death and humiliate him after a near rape.

Nor is Cooper fooled by Hayward’s desperation to save her husband. He has seen through her as clearly as he has Mitchell or the vaquero. She is guilty because she doesn’t love her husband, afraid he will die having gotten himself killed trying to prove he was worthy of her. Like the others, she is seeking redemption for herself as much as rescue for her husband.

Cooper can read them all because he knows himself. All but Widmark, the enigmatic gambler who talks too much too easily and says so little. Widmark’s ability to play both hero and villain plays a major role here, because neither Cooper or the viewer knows exactly where the cards will fall with him.

There is also a fairly subtle sense in the film that Widmark’s character is seduced almost as much by Cooper’s honor and sense of himself as he is by Hayward or the gold. Widmark will use the same almost homoerotic subtext in his role opposite Robert Taylor in The Law and Jake Wade.

It’s a mark of his qualities as an actor that the manages it without seeming the least weak or effeminate, He simply conveys that his character finds something missing in himself — or something he fears is missing in himself — in the strong silent and competent Cooper.

Finally they reach the valley and enter along a narrow cliff trail. The Apaches let them in with no trouble, though they watch them from every shadow. They will not let them out as easily.

They find the husband, Hugh Marlowe, alive, half mad, tormented by the Apaches who have made a game of watching him die, in pain, and bitter at Hayward who he blames for his own weakness and whom he half feared would abandon him, half feared would return and make him face again that he is a weakling, a failure, and unworthy of her..

Meanwhile Mitchell and the vaquero have gold fever. Only Cooper and Widmark know their problems have just begun.

Once they rescue Marlowe from the mine they set out to leave the valley.

One by one the Apaches pick them off. The vaquero, Mitchell, and finally Marlowe who sacrifices himself to save Hayward, earning in death what he could never find in life.

But Cooper, Hayward, and Widmark make it to the narrow cliffs in a running battle. There is one spot where a single man with a rifle could hold off the Apache while the others escape. They cut cards. Widmark stays behind.

Cooper gets Hayward out, but has to go back. He says it is because Widmark cheated at the card draw, then admits: “I was wrong about him, I have to tell him.” He returns in time to find Widmark wounded and dying with a quip and laugh on his lips. As the setting sun turns the valley to gold, Cooper says bitterly: “If the earth was made of gold, men would still die for a handful of dirt.”

He rejoins Hayward and they ride away.

Veteran director Henry Hathaway directed Garden of Evil from a literate script by Frank Fenton. The score is by Bernard Herrmann and does much to lift the film above its western origins; it is one of his best works.

The location cinematography by Milton Krasner is stunning, and few films of the era use technicolor as effectively. The location shooting looks like no other western of the period.

Like many simple adventure films Garden of Evil has things to say. At the time it must have seemed like just another good adult western, but through the looking glass of time we can see that the rare skills of the cast, director, script, score, and cinematography came together in ways that surpassed its origins.

It may seem a simple adventure story about men and a woman and their desires, dreams, hopes, and fears, but there is more here.

This is the type of film they mean when they say they don’t make ’em like that anymore. It has the thrills of a Saturday matinee or a serial, but it also has things to say about all of us, about why men and women risk their lives for dreams and for love.

Within the confines of a western it has something to say about loss, dreams, loyalty, and what those things can cost and are ultimately worth. Cooper is a man who has lost his dreams and regains them. Widmark, a man who never let himself dream, finds a woman worth desiring and a man worth dying for. Hayward’s obsession costs four men their lives, but she saves her soul and redeems herself as a woman.

Like Adam and Eve, she and Cooper are reborn, but in innocence this time, emerging from what an old padre called the garden of evil.

“If the earth was made of gold, men would still die for a handful of dirt.” Or for a woman’s love, honor, and a chance at redemption.

Sat 27 Jun 2009

ERICA QUEST – The Silver Castle. Doubleday Crime Club, hardcover, 1978. Reprint hardcover: Detective Book Club, 3-in-1 edition, Sept-Oct 1978.

The discovery that Gail Sherbrooke’s father, who she’d thought dead for over twenty years, had just committed suicide in Switzerland sends the aspiring young artist off on a search to learn the truth about a man she had never known.

Lying just beyond her reach she finds both mystery and romance — the type of story most readers surely find done far too often, and rather badly, too.

That’s not at all the case here. With much of the charm and intricacy of a hand-made Swiss clock, this is indeed an uncluttered detective story that’s both haunting and wholly enchanting.

– From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 3, No. 3, May-June 1979. This review also appeared earlier in the Hartford Courant.

Bibliographic data: [Taken from the Revised Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin]

QUEST, ERICA. Pseudonym of John Sawyer & Nancy Buckingham Sawyer; other pseudonym: Nancy Buckingham

The Silver Castle (n.) Doubleday 1978

The October Cabaret (n.) Doubleday 1979

Design for Murder (n.) Doubleday 1981

Death Walk (n.) Doubleday 1988 [Kate Maddox]

Cold Coffin (n.) Doubleday 1990 [Kate Maddox]

Model Murder (n.) Doubleday 1991 [Kate Maddox]

Deadly Deceit (n.) Piatkus 1992 [Kate Maddox]

I believe the Sawyers were British, but their books as Erica Quest were published only in the US. I seem to have avoided the issue somewhat in my review, but if The Silver Dagger were to be assigned to a genre, I don’t believe it could be called a Gothic. “Romantic suspense,” perhaps, but with a solid core of detection involved, if I can rely on the statement made above by my younger self.

(Bolstering the detective content of the Quest books is a discovery, made only this evening, that the series character who appeared in their last four books is actually Detective Chief Inspector Kate Maddox.)

Many of the books the Sawyers wrote as Nancy Buckingham were published only in England; most of the ones that appeared in the US were published in paperback as Gothics by either Ace or Lancer. A typical title might be The Legend of Baverstock Manor (Ace, 1968), which was originally published in the UK as the noticeably less striking Romantic Journey (Hale, 1968).

The Sawyers also wrote many straight romances, using the additional pen names Christina Abbey, Nancy John, and Hillary London for many of these. A list of these, along with some covers, can be found on the Fantastic Fiction website.

Sat 27 Jun 2009

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[10] Comments

THE BACKWARD REVIEWER

William F. Deeck

ELLERY QUEEN – The Scarlet Letters. Little Brown, US, hardcover ,1953; Gollancz, UK, hc, 1953. Included in the omnibus volume The New York Murders, Little Brown, US, no date [1958]. Paperback reprints include Pocket Books #1049, 1955; Signet Q5362, 1973, with many later printings from each publisher.

Dirk Lawrence, not too successful mystery writer and even less successful “serious” writer, and his rich wife, Martha, have a perfect marriage. Perfect, that is, until Dirk begins to suspect that his wife is cuckolding him and becomes drunken and violent.

Nikki Porter, Ellery Queen’s secretary, is a friend of Martha’s. Despite his quite correct protests that he is no good at such things, she gets Queen involved in the domestic discord.

Queen does a lot of running around and very little deducing. As a private-eye type, he’s futile, and he admits it. Private eyes “tail” people; Queen “trails” them.

It is evident to anyone with the meanest intelligence — which this reader possesses on a good day — what the outcome of this case will be. So with vast anticipation the reader waits for Ellery Queen the author’s twist, the final surprise, the revelation that nothing is what it seems. Most surprisingly, the shock is that everything is indeed exactly what it seems.

Those who have knowledge of the Queen saga may recall an earlier novel in which Biff Barnes or Barnes Biff or Beau Rummell or someone with a name like that, a partner with Queen in an investigative agency, pretended he was Ellery Queen.

That, I believe, is what happened here, without Ellery Queen the author bothering to reveal it. Good lord, even Sergeant Velie could have figured out the dying message the moment it was written, yet this Ellery Queen dithers about it for days.

Nonetheless, despite the obviousness of the plot and Queen the detective’s dimwittedness, there’s an engrossing novel here.

– From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 10, No. 3, Summer 1988.

Next Page »