May 2014

Monthly Archive

Sat 31 May 2014

REVIEWED BY MARVIN LACHMAN:

ANTHONY ABBOT – About the Murder of a Man Afraid of Women. Farrar & Rinehart, hardcover, 1937. No paperback edition.

A writer who was once tremendously popular, Anthony Abbot, is no longer read today. That is unfortunate because a recent reading (or in some cases rereading) of his books, published between 1930 and 1943, shows them to be still quite readable. In addition to a nostalgic look at New York in the past, there are plots far more imaginative than many conceived today.

The general caliber of writing is not good, but there are some touches that are surprisingly effective. For example, in the book reviewed below, Abbot describes a police lab, drawing an analogy to the medieval attempts to turn baser metals into gold. “Here, instead, men sought to turn human flesh and blood into grand jury indictments.â€

Abbot, the pseudonym of Fulton Oursler, author of the best seller The Greatest Story Ever Told, is usually lumped with another pseudonymous writer, his contemporary, S. S. Van Dine. There are definite similarities, although Oursler eschewed the erudition and footnotes which caused Ogden Nash to threaten to kick Van Dine’s creation [Philo Vance in the pants]. Abbot’s Thatcher Colt, like Philo Vance, is larger than life, but he is easier to take. Both authors have “Watsons†whose names are the author’s pseudonyms and who record the adventures of their employers. Each series has a somewhat dense District Attorney.

Another similarity is the use of real murder cases for many of the novels. There was a time when mystery novelists like Van Dine, Patrick Quentin, Anthony Boucher, John Dickson arr, and Abbot were very knowledgeable about the great true crimes of the past. In the first Thatcher Colt book, Abbot has the detective, who owns a library of 15,000 true crime books, ask, Ãf our criminals plagiarize from the past, why not our detectives?

Much has been written about Abbot’s second mystery, About the Murder of the Clergyman’s Mistress (1932) and its basis in the Hall-Mills case of 1922. I do not recall anyone pointing out that a lesser-known Abbot, About the Murder of a Man Afraid of Women (1937) is based on the William Desmond Taylor case, subject of two recent popular nonfiction books, though it clearly is.

Man Afraid of Women has Thatcher Colt due to get married in a few days and frustrated by such problems as auto deaths, lack of adequate gun control, and pervasiveness of drugs in New York City. There is also a reference to air pollution. (Sound familiar?) Of historical interest is the attitude of the characters toward blacks, an outrageous racism as prevalent as the anti-Semitism found in British novels of the period between the wars.

Colt’s fiancee sends him the problem of a secretary with a missing boyfriend, and that soon leads to the titular murder victim. The puzzle is a difficult one, and while the solution is not totally satisfactory, there is some real misdirection along the way and an exciting, albeit melodramatic, ending.

Sometimes the writing is overheated, as when Abbot refers to this case as “the greatest of crime problems.” It’s not, but it’s a good puzzle nonetheless.

Besides plot surprises, there is some dialogue that we would not expect. Coitus interruptus in a mystery written in the 1930s! Colt’s “Watson,”Anthony Abbot, is upset by Colt’s impending marriage and retirement. He asks his wife, Betty, “Why had a woman come back into the life of the greatest detective of all time?” Abbot’s wife claims he is jealous and sits on his knee. We read, “I spanked her and took her to bed. And then came one of life’s embarrassing moments, for shortly thereafter the telephone rang. Thatcher Colt was at the other end of the wire.”

— Reprinted from The MYSTERY FANcier,

Vol. 13, No. 2, Spring 1991.

NOTE: For Mike Nevins’ review of About the Murder of the Clergyman’s Mistress earlier on this blog, go here.

Sat 31 May 2014

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[3] Comments

THE ARMCHAIR REVIEWER

Allen J. Hubin

ROBERT B. PARKER – Perchance to Dream. G. P. Putnam’s Sons, hardcover, 1991. Berkley, paperback, 1993.

I know I should have boned up on Raymond Chandler before tackling Perchance to Dream, Robert B. Parker’s sequel to Chandler’s The Big Sleep. But I didn’t, and my reading of Chandler was so long ago I can make no comparisons. I can say that, on its own, I found Perchance a wholly delightful treat.

Philip Marlowe is called back to the Sternwood mansion. General has died, but Vivian Sternwood still lives there. And her psychopathic sister Carmen, tucked away among the white coats in Sleep, has gone missing from Resthaven Sanitorium. So Marlowe goes looking.

Resthaven is run by a sleazeball doctor named Bonsentir, who is so well connected that police bow and scrape and wag their tails. Vivian has a gangster bedmate named Eddie Mars, and he’s mixed up in this as well. Marlowe is not easy to discourage, though various folks try in their own nasty ways, and he’s likely either to get dead or to the bottom of what’s going on…

Smooth of action, full of good lines and sharp images, this went down in one satisfying gulp.

— Reprinted from

The MYSTERY FANcier,

Vol. 13, No. 2, Spring 1991.

Fri 30 May 2014

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[5] Comments

THE BACKWARD REVIEWER

William F. Deeck

JAMES R. LANGHAM – Sing a Song of Homicide. Simon and Schuster, hardcover, 1940. Popular Library #63, paperback, no date [1945]. Film: Paramount, 1942, as A Night in New Orleans (with Preston Foster & Patricia Morison; screenwriter: Jonathan Latimer; director: William Clemens).

Gun in hand and chuckling, Samuel Grace Abbott is standing by the recently deceased Harvey Wallace. Wallace is so recently deceased that the three bullet holes around his heart are still bubbling. A blackmailer, Wallace made at least one mistake: He tried to extort money from Abbott’s wife, Ethel. In addition, he was generally just not a nice person.

As an investigator in the district attorney’s office, Abbott is assigned to aid the police in solving Wallace’s murder. Obscuring his involvement, planting evidence to mislead the police, and staying a step, sometimes two, ahead of the authorities and some crooks that he encounters along the way require nimble brain work. Abbott’s stratagems are most entertaining.

Perhaps the best part of the book is Ethel, a delightful young lady. Yet if there is a weak point, it is the assumption that Ethel was capable of writing letters containing material that could be employed for blackmail.

Langham says that once he knew he could do something, it stopped being fun. Though he contends on the back wrapper of the paperback edition of this novel that “writing is still fun,” he wrote just one other mystery. It, too, features the Abbotts, who should not be confused, as I unwittingly did, with Francis Crane’s Pat and Jean Abbott. Langham’s second novel is A Pocket Full of Clues; if it is as good as this one, you should start looking for both of them.

— From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 13, No. 2, Spring 1991.

Thu 29 May 2014

Reviewed by DAVID VINEYARD:

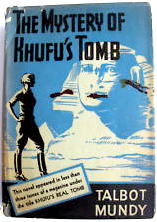

TALBOT MUNDY – The Mystery of Khufu’s Tomb. First published as “Khufu’s Real Tomb” in Adventure magazine, October 10, 1922. First book edition: Hutchinson & Co., UK, hardcover, 1933. First US edition: D. Appleton-Century Co., hardcover, 1935. Several other reprint editions exist. (Follow the link to an online edition of the pulp magazine version.)

Talbot Mundy’s career was as strange as anything he wrote, and that is no small statement. A con man and adventurer in India he came to the United States, nearly died, saw the light, and reformed by becoming a writer, almost immediately penning a number of classics such as Rung Ho!, The Eye of Zeitoon, and Hira Singh. He shot to the top of the list of Haggard and Kipling successors and stayed there until his death, his work a staple in the pulps, particularly the grand old pulp icon, Adventure.

His King of the Khyber Rifles was twice filmed, a bestseller, and even adapted by Classics Illustrated, and his novel Jimgrim, or King of the World is considered by many, myself included, the greatest achievement of the adventure pulps.

Jimgrim featured one of Mundy’s series heroes (Tros of Samothrace, the Greek trader and opponent of Caesar and Cleopatra, is his other great creation), the American Captain James Schyler Grim, in the service of His Majesty’s Secret Service in the Middle and Near East. With his ally and friend Jeff Ramsden, his Sikh friend Naryan Singh, his Indian Secret Agent companion Chulander Ghose, and a small army of Mundy’s other heroes (Athleston King and Cottswold Ommony among them) he battles to keep the Middle East, Palestine in particular, from exploding.

All of that fairly standard British Raj rah rah rah save for one fact: Talbot Mundy was no admirer of the Empire and stood for self-rule in India and the Middle East. It was a unique view of the world for an adventure story writer in that era. There is little racism or jingoism in Mundy.

Later in life Mundy became obsessed with the philosophy of Theosophy, a semi-mystical religious movement out of Madame Blatavasky and the Golden Dawn. That would have ruined a lesser writer. In Mundy’s case it inspired his finest novels and most loved tales, Om: The Secret of Ahrbor Valley, The Nine Unknown, The Devil’s Guard, Full Moon, and Jimgrim.

The change in his work showed first in the Jimgrim tales in Adventure, where Grim and company left the British Army and Secret Service behind and took up with American millionaire Meldrum Strange who financed their adventures from there on. And what adventures they were, a search for what happened to all the coins minted in the ancient world (they were hidden beneath the Ganges by the Nine Unknown), a war of good and evil on the roof of the world where the Black Lodge is challenged by the White, and the final novel of the series, Jimgrim, in which the world must be saved from a fanatical madman, leading to a finale that still stuns the unsuspecting reader today and never fails to bring a tear to my eye.

In the transition period from the heyday of the series to the later deeper novels Mundy’s best is the Jimgrim adventure The Mystery of Khufu’s Tomb.

It begins when engineer Jeff Ramsden is nearly run off a road on the Geiger Trail near Virginia City by Joan Angela Leich, the kind of headstrong heiress who was common in fiction of the time. Joan and Jeff are old friends though, and she has nearly gotten him killed before.

She’s tall — maybe a mite too tall for some folks’ notions– and mid-Victorian mammas would never have approved of her, because she’s no more coy, or shy, or artful than the blue sky overhead. She has violet eyes, riotous hair of a shade between brown and gold, a straight, shapely little nose, a mouth that is all laughter, and a way of carrying herself that puts you in mind of all out-doors. I’ve seen her in evening dress with diamonds on; and much more frequently in riding-breeches and a soft felt hat; but there’s always the same effect of natural-born honesty, and laughter, and love of trees and things and people. She’s not a woman who wants to ape men, but a woman who can mix with men without being soiled or spoiled. For the rest, she’s not married yet, so there’s a chance for all of us except me. She turned me down long ago.

That’s Joan all over, and a welcome breath of femininity she is in Mundy’s masculine world. She is also guaranteed trouble, and here is no exception. This time she has gotten involved with one Mrs. Isobel Aintree, a fatale femme with a cobra’s bite that Ramsden and Grim have battled before. Joan needs help concerning a purchase made while in Egypt during a revolution (the more things change …) where she “…went and bought a lot of land that everybody said was no good because it was too far from the Nile.”

Now a man called Moustapha Pasha (“…there are men of all creeds and colours, who can mouth morality like machines printing paper money, but who you know at the first glance have only one rule, and that an automatic, self-adjusting, expanding and collapsing one, that adapts itself to every circumstance and always in the user’s favour. This man was clearly one of those.”) wants the land and won’t take no for an answer, but Joan is too stubborn to ever yield.

Just what is on that land that Mrs. Aintree wants it and Moustapha Pasha is willing to bribe Ramsden to betray Joan to the tune of one million dollars (1920‘s dollars at that)? Mrs. Aintree wants it so bad she marries Moustapha Pasha. The answer must be in Egypt, and anywhere east of the Pillars of Hercules there is no better man to have on your side than Jimgrim, so Joan hires Meldrum Strange’s team to help her.

As usual Grim knows more than might be expected:

The men who are interested are keeping it awfully quiet among themselves, but Narayan Singh and I have overheard some talk, and the figure they name would make the Federal Reserve Board blink — fifty million pounds, or say two billion dollars!”

“Let’s hope it’s true!” said I.

“Let’s hope it isn’t true!” Grim answered. “Any such sum of money as that would turn Egypt into Hades! If it’s there it means civil war, whoever gets it!â€

Two billion dollars and the fate of Egypt, just the sort of thing Grim lives for.

And they are off with the help of a Chinese astronomer, Chu Chi Ying, and it is no real mystery what lies beneath Joan’s land.

“…when they got to the so-called King’s Chamber it was empty. There never had been anything in it. Khufu was supposed to be buried in it, but he wasn’t. He was the richest Pharaoh Egypt ever had. He must have been, or he couldn’t have built the Pyramid. Where was he really buried, and what did he do with his money?”

So if Khufu, Cheops, money is not in the Great Pyramid of Giseh, where is it? Want to hazard a guess?

Our band of heroes must deal with enemies on all sides and excavate the treasure that Khufu flooded under Joan’s land without drawing too much attention. Mundy never made things easy for his heroes. You may even wish he had, because the danger, sweat, set backs, short-lived victories, and sheer impossibility of the task will leave the reader almost as stretched as the heroes.

And it can only get worse, as Grim battles the forces of Moustapha Pasha and Mrs. Aintree above ground while Jeff and Joan are trapped underground avoiding death traps laid by the determined Khufu, and up against blind mutated giant albino crocodiles.

Long before Indiana Jones, Clive Cussler, and James Rollins Mundy’s heroes were knee deep in the kind of adventures readers today savor. Today’s heroes rely on relentless action though, and while there is no shortage of action and movement, Mundy’s heroes use their brains first, then their brawn.

That is one reason Mundy remains not only readable, but fresh and entertaining to read when so many others have been passed by. It isn’t hard to see the influence he had on Robert E. Howard, Philip Jose Farmer, and Fritz Leiber as well as a generation of adventure writers. His name still triggers images of exotic locales and high adventure in the wild places as much as Rider Haggard before him.

I’ll give Mundy, via Ramsden, the last perfect words:

In Singapore, in a little side street that runs down toward the quays, there lives a Chinaman named Chu Chi Ying, who teaches no more “fat-fool first mates” how to pass examinations for their master’s ticket, but smiles nearly all day long and amuses himself by making marvellous astronomical calculations. He seems to have an income quite sufficient for his needs, and a portrait of Joan Angela hangs on the wall just inside the doorway of his house. Go and look, if you don’t believe me. On your way, consider the stuffed, blind, white crocodile in the Gezivich Museum, Cairo.

I don’t see that adventure today is in any better hands.

Wed 28 May 2014

Reviewed by JONATHAN LEWIS:

ARMORED CAR ROBBERY. RKO Radio Pictures, 1950. Charles McGraw, Adele Jergens, William Talman, Douglas Fowley, Steve Brodie, Don McGuire, Don Haggerty. Director: Richard Fleischer.

Armored Car Robbery is a heist film/film noir directed by Richard Fleischer (Fantastic Voyage, The Vikings). Filmed on location in Los Angeles, the film stars Charles McGraw (The Narrow Margin, Spartacus) as Lt. Jim Cordell. He’s tasked with tracking down a gang of four criminals responsible for a fatal armored car robbery. While the film’s acting isn’t particularly memorable, it benefits considerably from a solid plot, believable criminal characters, and its postwar Los Angeles setting.

William Talman (Perry Mason) portrays Dave Purvis, a greedy and ruthless piece of work who isn’t above murdering anyone who gets in his way. Early in the film, Purvis convinces the down on his luck Benny McBride (Douglas Fowley) to join him in an armored car job. McBride is still very much in love with his burlesque dancer wife, Yvonne LeDoux (Adele Jergens). Problem is: she’s not in love with him. In fact, she’s carrying on a dalliance with Purvis.

Purvis and McBride, along with two other men, Al Mapes (Steve Brodie) and William “Ace†Foster (Gene Evans) hold up an armored car outside Los Angeles’s Wrigley Field, a baseball stadium. Of course, things don’t go as planned. The timing of the operation is off and the cops arrive on the scene too soon. Lt. Cordell’s partner is killed and McBride is wounded.

The four ill-fated criminals flee the scene by automobile, driving past the Los Angeles oil fields and toward the harbor. Tensions between the men reach a boiling point. Funny thing: newly, and illicitly, acquired cash seems to do that to a certain class of criminals. Unsurprisingly, Purvis ends up shooting and killing the already wounded McBride. After all, Purvis not only after McBride’s share of the loot; he’s after his cheating wife.

Soon after, Lt. Cordell and the police arrive at the harbor and begin their extensive manhunt for the criminals responsible for the heist. For a good portion of the rest of the film, we see Cordell and his new rookie partner in pursuit of an increasingly reckless Purvis. This cat-and-mouse chase culminates in an impressive, tension filled showdown at an airfield where the doomed ringleader forgets to look both ways before he runs across a runway.

Although it’s a relatively short film, running just over an hour, there’s more than enough action and suspense to keep one engaged throughout the film. The Los Angeles settings are spectacular. From the ballpark to the oil fields, from the harbor near the San Pedro to a motor lodge, one feels transported back in time to 1950 Southern California.

The weakest part of the film is the dialogue. There just aren’t all that many memorable lines in the film, at least none that will stay with you for any considerable amount of time. But then again, one does not watch movies such as Armored Car Robbery primarily for the acting or for the dialogue.

In conclusion, though, Armored Car Robbery is a real gem. If you haven’t seen it already, it’s definitely worth consideration. If you’ve seen it long ago, it’s worth a second look. It’s definitely a lesser-known film, but it’s one that stands up to the test of time. Armored Car Robbery may not be a classic, but it’s still a perfectly good heist film and one of Fleischer’s earlier works that doesn’t get nearly as much appreciation as it deserves.

Tue 27 May 2014

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[4] Comments

THE BACKWARD REVIEWER

William F. Deeck

S. S. VAN DINE – The Winter Murder Case. Charles Scribner’s Sons, hardcover, 1939, with introduction and “Twenty Rules for Writing Detective Stories.” Reprint editions include: Otto Penzler Books, paperback, 1993.

According to the introduction by an anonymous editor, Van Dine went through three stages with a novel — a 10,000-word synopsis of the plot, a second, longer development of the novel, and then the final, full-length version.

Published posthumously, Winter had reached only the second stage. Thus, the footnotes, furbelows, and elaboration of character and incident one expects from Van Dine are missing here. So, too, I would contend, is anything but a rudimentary plot.

As a Van Dine admirer, ostensibly one of the few extant, I was embarrassed for him by the publication of The Gracie Allen Murder Case. This one adds to my embarrassment. For Philo Vance completists only.

— From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 13, No. 2, Spring 1991.

Editorial Comment: Those wishing to read this book and decide for themselves may find an e-version online here.

Mon 26 May 2014

Reviewed by JONATHAN LEWIS:

THE HEROES OF TELEMARK. Columbia Pictures, 1965. Also released as Anthony Mann’s The Heroes of Telemark. Kirk Douglas, Richard Harris, Ulla Jacobsson, Michael Redgrave. Director: Anthony Mann.

The Heroes of Telemark, directed by Anthony Mann, is both a drama and action film about the Norwegian resistance during the Second World War. Filmed on location, it is one of Mann’s (Winchester ’73, El Cid) last movies.

Film historian Jeanine Basinger, while not oblivious to its flaws, rightly categorizes The Heroes of Telemark as “a grand, epic adventure with moments of incredible tension.†The DVD version, with its widescreen ratio, is perhaps as close as one can get at home to the experience of watching it in a movie theater.

The film’s plot, loosely based on actual events, centers around two characters, Oslo university physicist and womanizer turned resistance fighter, Rolf Pedersen (Kirk Douglas looking consistently angry and determined) and Knut Straud (a character portrayed by Richard Harris and based on American-born Norwegian resistance leader, Knut Haukelid).

Assisting them are Pedersen’s ex-wife, Anna (Ulla Jacobsson) and her uncle (Michael Redgrave). Their mission: to destroy a heavy water plant in the Norwegian county of Telemark that the Nazi occupying forces are utilizing in their race to develop atomic weaponry before the Allies are able to do so. The fate of the world depends upon them, and they know it.

The Heroes of Telemark is not simply an action film. It’s also a character study of Pedersen, a reluctant hero. When we first encounter him, he’s in his laboratory in Oslo engaged in a dalliance with a student. He is initially hostile to the Resistance, blaming Straud and others for provoking Nazi retribution tactics against Norwegian civilians. He only joins the cause when he learns what the German invaders are up to in Telemark.

Complicating matters are his still strong romantic feelings for his ex-wife (Jacobsson). Pedersen also repeatedly butts heads with Straud over the best methods by which to achieve their goals. Pedersen is much more ruthless than Straud and cares far less about so-called collateral damage. This will change by the time the film ends, with Pedersen regaining some of the humanity he lost in his ruthless fight against the Nazis. Overall, Douglas is successful in this role, even if his portrayal of the hotheaded Pedersen does begin at times to feel a bit one-dimensional.

Aside from the strong plot, the film benefits from often stunning imagery and visuals. The scenes shot on location in Norway are quite spectacular. There are also numerous shots of bridges, motor vehicles, ships, staircases, and doorways. All of these are, of course, man-made creations that provide stark contrasts to the region’s snow covered natural beauty.

There’s one scene in particular that merits close attention. This occurs toward the end of the film with a black train is pulling into a station, set to board a ferry. Look, in particular, for the red light shining onto the white snow, the white steam rising from the train’s engine, and the small, but noticeable yellow light at the front of the train. Little details such as these give the film an immediacy that is lacking in all too many contemporary films that rely too heavily upon special effects to deliver visual messages.

Sound also plays a prominent role in the film, be it the aforementioned train’s whistle, the ticking of bombs, or the dripping of heavy water in the plant (also a strong visual). The buzz of the ferry’s engines, again at the end of the film, is also very noticeable.

In conclusion, The Heroes of Telemark is worth watching. Those familiar with Alastair McLean’s oeuvre might especially appreciate it. The history of Nazi Germany’s quest to develop the atomic bomb has been largely forgotten. Yet it remains an important chapter in the history of the Second World War, along with the story of the Norwegians who sacrificed their lives and homes to stop the heavy water project.

The Heroes of Telemark isn’t one of the best war films ever made, but it’s still a very good one.

Mon 26 May 2014

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[5] Comments

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

MARGERY SHARP – The Tigress on the Hearth. Collins, UK, hardcover, 1955. No US edition.

At 125 smallish pages, with wide margins, big type and illustrations no less, this is not so much a novel or even a novella as a shaggy dog story about Victorian manners and murders.

Young Hugo Lutterwell, is a member of the landed gentry, hunting in Albania of all places, who gets separated from his party and fires a shot in the air to locate them. However it seems he’s not a terribly proficient marksman because his shot misses the sky and kills a farmer’s dog. Hugo suddenly finds himself mobbed and about to be killed by the farmer when a lovely young woman jumps into the fray, fatally knifes the farmer, and escapes with Hugo.

In less time than it takes to tell (as they say) the two are happily married and back in England, where Hugo finds it a bit difficult to explain to his bride that although he’s very grateful to her for saving his life, and it was wonderful of her to do it, knifing a man isn’t the sort of thing one admits to in polite society.

He finally manages to convey to her that there are things a gentleman simply doesn’t do, but a lady is not bound by conventions except that she shouldn’t talk about killing people, a coda that leads to years of wedded bliss — until a local scoundrel starts making trouble for Hugo, who cannot retaliate because (as he explains to his wife) there are some things a gentleman simply doesn’t do….

But….

What follows is a short, cheerful and pleasantly amoral bit of foul play, followed by a spot of polite detecting and a sedate wrap-up in the coziest tradition. Tigress on the Hearth is a slight thing, but I think I’ll remember it.

Sun 25 May 2014

Reviewed by JONATHAN LEWIS:

“NO TIME LIKE THE PAST.” An episode of The Twilight Zone, CBS, 7 March 1963 (Season 4, Episode 10). Dana Andrews, Patricia Breslin, Malcolm Atterbury. Radio adaptation: The Twilight Zone Radio Dramas, syndicated, circa 2002-2003, starring Jason Alexander.

“No Time Like The Past” is a Twilight Zone original series episode starring Dana Andrews (Laura, Where the Sidewalk Ends) as Paul Driscoll, a time-traveling physicist who comes to realize that, no matter how much you may want to, you simply can’t change the past. It’s one of those Twilight Zone episodes, which, apart from the somewhat clunky-looking scientific equipment one sees in beginning, does not seem remotely dated.

Indeed, the plot of “No Time Like The Past” and its theme of fatalism seem as timely as ever. That is one reason why Jason Alexander’s (Seinfeld) portrayal of Driscoll in the radio and audio drama version works so well.

We begin with Paul Driscoll (Andrews) in conversation with his colleague, Harvey (Robert F. Simon). They’re in a laboratory. Driscoll is standing in a crude time machine that he invented. Light and shadow play prominent roles, both literally and figuratively, in this scene. A man of both academic knowledge and unbridled humanism, Driscoll has an incredibly bleak view of the twentieth-century and he’s not remotely reluctant to make his views crystal clear:

“We live in a cesspool, a septic tank, a gigantic sewage complex in which runs the dregs, the filth, the misery-laden slop of the race of men.â€

It’s Driscoll’s intention to travel backward in time so as to change the present. He chooses three destinations: Hiroshima, in order to evacuate citizens before the atomic bomb is dropped; Nazi Germany before World War II, so he can assassinate Hitler; and on board the Lusitania, to halt the American entrance into the First World War. (In the radio play, Driscoll visits the same three points in time but in reverse order.) In all three situations, he fails to complete his task. He returns, disappointed, to the present and once again meets up with Harvey in the laboratory.

Driscoll now has a new plan. Rather than trying to change the past, he opts for living in it. Specifically, he wants to go back to 1881 and live in Homeville, Indiana where he can enjoy band concerts and lemonade. He’s read a book about the Midwest in the nineteenth-century and decides he wants to live in simpler times, before world wars and atom bombs. His naivety is galling.

When Driscoll gets to Homeville, he soon realizes that the past may not be all that great either. He ends up living in a boarding house with an armchair warrior who advocates for American imperialism in East Asia and, within a couple of days, President James Garfield is shot. Complicating matters is the fact that he begins to have romantic feelings for a schoolteacher, Abigail Sloan (Patricia Breslin) but soon realizes that he can’t do anything about it, lest he change the course of History.

Things get even worse for Driscoll when he realizes that some of Sloan’s schoolchildren are going to die in a fire. He read about it in the history book he carries with him. A man divided against himself, he can’t decide if he should intervene. In a sadly ironic twist of fate, Driscoll inadvertently ends up causing the very historical event he intended to stop. One of the perils of time travel, no doubt. Driscoll finally accepts that the past, as Harvey told him all along, is indeed inviolate.

Dana Andrews, best known for his film work in the 1940s, skillfully conveys the conflicted emotions the hopelessly tormented Driscoll. He convincingly portrays a man who is angry and sentimental, fearful and hopeful. In the slightly modified radio show version, Jason Alexander successfully pulls off the quite difficult feat of bringing this episode to life without the benefit of visuals. Alexander’s voice acting never once reminds you of his portrayal of George Costanza on Seinfeld.

In conclusion, “No Time Like The Past” is a classic Twilight Zone episode that stands up to the test of time. The themes of nostalgia, sentimentalism, and wishing one could change the past so as to change the present remain poignant today.

While some contemporary listeners might be less familiar with the Lusitania than with the Second World War, the points in time that Driscoll visits remain alive in the American public consciousness. One could imagine a future reworking of the script to include references to the Vietnam War and to 9/11, but that might have to wait another couple of decades. It’s an episode both worth watching and listening to.

NOTE: The TV episode can be watched in its entirety on IMDb here.

Thu 22 May 2014

Reviewed by DAVID VINEYARD:

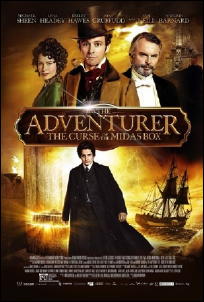

THE ADVENTURER: THE CURSE OF THE MIDAS CUP. 2013. Anuerin Barnard, Michael Sheen, Sam Neill, Ioan Gruffudd, Lena Hedley, Catherine Hawes, Mella Carron, Xavier Atkins. Screenplay by Christian Taylor and Matthew Huffman, based on the young adult novel Mariah Mundi and the Midas Box, by G. P. Taylor. Directed by Jonathan Newman.

This is a mildly entertaining steampunk juvenile tale based on a series by G. P. Taylor, about a young lad named Mariah Mundi (Anuerin Barnard) who is at that awkward age between man and teen. The plot takes a note from Clive Cussler and James Rollins rather than Harry Potter or Percy Jackson, with the McGuffin a mysterious gold box that has the power to turn anything into gold, and Mariah a reluctant young hero forced into improvising a bit of Richard Hannaying (or should that be David Balfouring?) to find it and save his little brother who has been kidnaped by a ruthless master criminal.

Evil Otto Luger (Sam Neill) knows the box can give life or destroy it and he wants the power along with the evil mastermind behind him, the mysterious Gomberg.

All of which leads to London where Mariah is attending a lecture by his father along with his mother and his brother Felix (Xavier Atkins). In short order Captain Will Charity (Michael Sheen) shows up seriously wounded by Luger to warn the Mundi’s of Luger’s quest, seems he and Mariah’s parents (Ioan Gruffudd and Catherine Hawes) are secret agents for the Bureau of Antiquities, and have dealt with ruthless Otto before.

Charity takes off (he’s always doing that then popping up at convenient times), the Mundis disappear, and Mariah and Felix are fleeing Luger’s men in their robes and night clothes before the night’s over, but not before their mother gives each of them half of an amulet and a mysterious bit of doggerel to remember.

Charity pops in to rescue Mariah in time to save him from Luger’s men but Felix is captured, Luger now has half of the amulet, and Mariah finds himself on the way to a remote North Sea island where Luger owns the fabulous Prince Regent resort built right into the mountainous island. Mariah, disguised as a porter, is to seek Felix, and of course Charity takes a hike again. His parents he is told are most likely dead at Luger’s hand, which causes much less angst than you might expect.

Mariah soon discovers that children on the island have been disappearing and no one ventures out after dark because of a monster. Nor is his job easy what with dodging Luger’s men who know his face, Monica (Lena Hedley) the evil female manager of the hotel, Luger himself, and a flamboyant Russian escape artist who shows up adding to the mystery.

With Sacha (Mella Caron), a parlor maid who befriends Mariah, he begins to delve into the mystery, and soon learns Luger is looking for the Midas box beneath the hotel in the mountain. The healing waters the hotel is famous for taking their powers from the box.

Complications pile on: Mariah makes some fair deductions and some narrow escapes with Sacha, a set of magic gypsy cards, and a suit of Midas solid gold armor fit into the plot, two other mysterious men show up also working undercover, and just as Mariah seems about to discover the islands secret Charity appears (two guesses as who) and everything falls apart when he is discovered.

Mariah finds Felix and solves the mystery of the monster (you should be far ahead of him on most of this), but now Sacha is in danger too, Luger has both pieces of the amulet and the gold box, Felix is trapped in a tomb filling with water. Luger and the manager plan to gas them all and the other children forced to dig for the box in tight quarters, and even though the Bureau of Antiquities shows up they are no match for the mysterious box and the power that once destroyed Midas enemies.

You know Mariah will defeat Luger seeing to it that he meets an appropriately grisly end with the aid of that bit of doggerel his mother whispered to him, and Sacha’s drunken father will save her, dying with the evil manageress Monica. All is well, Mariah, Felix, and Sacha receive medals, Mariah asks Sacha to live with them, and they are told the Bureau may call on them again.

For now, Charity informs them, he is hunting Mariah’s living but missing parents and Gomberg, and Mariah has done “very well.â€

Roll the credits — but wait, there is still one revelation left, one so mind-numbingly stupid — I say stupid, but so stupid as to almost be brilliant — as to leave you stunned, but handled quite well, and certainly enough to get you to buy the next book or rent the next movie or at least take a peek in the bookstore.

It’s all playful and fairly inventive, a bit plot heavy and deliberate for today’s youthful audiences, but it doesn’t insult your intelligence, not until the last scene anyway. Fan’s of the books must have been pleased. It’s another film you will want to Netflix or Redbox rather than buy, but you likely will want to see it.

Barnard as Mariah is quite good and he fits the books illustrations well; with the right roles he might even develop as a popular actor. Neill has a fine time as Luger in one of his last roles, and Michael Sheen has fun as the extravagant Will Charity though none have more than one dimension or much chance to do more than sketch in their characters. The cast is uniformly good as are the special effects and sets, especially the hotel’s generators. You may wonder why they wasted Ioan Gruffudd (Horatio Hornblower) in such a minor role, but they really didn’t — but that’s for the sequel.

I may at least check out the books, and the film is entertaining. Though the start was a bit slow I liked it quite a bit, and wouldn’t mind seeing the sequel with the same cast and credits. It’s no match for the Harry Potter, Percy Jackson, or the Series of Unfortunate Events films, but for what it is it is handled well.

It’s actually better than this review, but I don’t want to mislead you. It’s an old fashioned adventure story owing more to Stevenson and Buchan than Rowling or Anthony Horowitz’s Alex Rider, and depending on your taste for that type tale, you will either love it or be entirely indifferent to it. It reminded me of the kind of thing Robert Lewis Taylor (The Travels of Jamie McPheeter and The Treasure of Matacumbe) used to write though not as brilliant or complex, or a juvenile version of some of Macdonald Hastings odder adventure stories. The chief difference being that there is no Alan Breck or Long John Silver character with dubious motives to spice things up. If, like me, you like that future-past genre of steampunk adventure and classic adventure tales, this is right up your alley.

If not, you may find it formulaic, and old-fashioned. It all depends on your fancy for this genre of adventure films. There is something missing here I can’t quite lay my hands on, but it may be as simple as the film is done by rote, and there is no real passion for the story as in the Harry Potter films.

It’s not enough to make a good movie of something like this, you have to love the material and the magic of bringing it to the screen. Without that it is basically a minor A or superior B adventure film and nothing more.

Classics are made when that extra element is present.

Next Page »