July 2009

Monthly Archive

Wed 29 Jul 2009

I’ll be leaving tomorrow morning for Columbus OH and this weekend’s 2009 PulpFest convention, the first under the new name and new management. They’ve done a tremendous amount of advertising and stirred up a lot of excitement about their show, more than there’s been in a long time. The fellows running the old PulpCon had done a good job over the years, but attendance had been dropping and they didn’t appear to be very receptive to new ideas.

PulpFest is primarily a venue for collectors of old pulp magazines to get together and talk about their recent acquisitions as well as those that got away, and of course to look for more. The center of the show is the dealers’ room, but in the evening are various panels and presentations, all in a very relaxed atmosphere. Many of the attendees have been coming for years, but anyone coming for the first time should feel welcome right away.

Some of you reading this I expect to see there, including several whose names should be familiar if you’ve been reading this blog for a while, such as Walter Albert, Walker Martin, Mike Nevins and Dan Stumpf. Stop by and introduce yourself if you’re there and I don’t see you first!

I’ll be back home on Sunday, but it may be a few days into August before the blog is very active again. Whenever I go away I pretty much stay off the computer, so no reports on the big bash until I get back. See you then!

Wed 29 Jul 2009

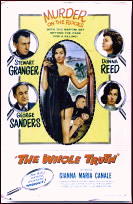

THE WHOLE TRUTH. Columbia-UK, 1958. Stewart Granger, Donna Reed, George Sanders, Gianna Maria Canale, Michael Shillo. Screenwriter: Jonathan Latimer, based on a play by Philip Mackie. Directors: Dan Cohen, John Guillermin.

Whenever you see Jonathan Latimer’s name somewhere in the credits of a film, you know that movie lovers in general are going to have a good time with it, and mystery fans in particular. The Whole Truth, although 1958 was beginning to be a little late for a movie to be filmed in black-and-white, is no exception.

And although Stewart Granger’s career was on the downswing by the time he made this film — besides North to Alaska and a lot of work on TV and Europe, I don’t see very much else in his later list of credits — he still does a good job playing a film director in Europe having problems controlling the temper of his Italian leading lady, played briefly but most effectively by Gianna Maria Canale, an Italian leading lady herself (in one of her few English language appearances).

It also turns out that Granger, while now happily married to Donna Reed, once had a short affair with Miss Canale, and the latter is holding that over his head — give me my way, she says, or your wife? Behave, or I’ll tell her everything.

I say “briefly” because, this being a murder mystery, Miss Canale’s death comes very early on in the movie. It is very tempting to tell you exactly what George Sanders’ role is in this picture, but suffice it to say that Granger’s character is suspected, and it is up to Donna Reed’s to put up a good front. It is obvious that she has doubts, however, when his story begins to be challenged from all directions.

There are many twists and turns ahead, not all of them wholly believable, but with Latimer in charge, the characters are not idiots — far from it. Sanders, of course, out acts everyone on the set, as only he could whenever given half a chance. There is lots of fun in store if you watch this one — giving, as, I say your suspension of disbelief plenty of room to work, and even to wallow around in.

As for it being filmed in black-and-white, as pointed out in my first paragraph above, I really think the movie ought to have been made in color, even if a good portion of it takes place at night. It looks like a color film with the color turned off, if that makes sense, not a 1940s black-and-white film made by people who knew exactly how to make black-and-white films.

Tue 28 Jul 2009

IT’S ABOUT CRIME

by Marvin Lachman

– This essay/review first appeared in The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 9, No. 2, March/April 1987. It is quite remarkable that Harper has kept Sayers’ detective fiction in print ever since, although different cover art is now used, and the prices are generally double those mentioned below (!). No changes have been made to update these comments since they were first published.

Harper’s Perennial Library keeps reprinting Dorothy L. Sayers, proving that there will always be an audience for class. In her lifetime Sayers published eleven Lord Peter Wimsey novels and three short story collections which included Wimsey stories. Perennial has now republished nine of the novels and all of the short story collections in uniform paperback editions at $3.95 each. (I suspect that the two remaining novels, The Unpleasantness at the Bellona Club and The Nine Tailors, will also be reprinted shortly.)

In addition, there is a trade paperback of almost five hundred pages, Lord Peter ($8.95), which contains all of the Wimsey short stories, including three that were never previously published in book collections. That book is enhanced by a James Sandoe introduction, an essay by Carolyn Heilbrun (who writes mysteries as Amanda Cross), and a delicious Wimsey parody, “Greedy Night,” by E.C. Bentley.

Speaking of bonuses, I must again praise the illustration by Marie Michal which appears on all of the covers. They’re some of the best done paperback art I’ve seen in years.

I’m not sure if there’s anything else about Sayers that hasn’t already been said. I could suggest that her non-series short stories not be overlooked since they are uncommonly good, especially “The Man Who Knew How,” in Hangman’s Holiday, as well as “Suspicion” and “The Leopard Lady,” in In the Teeth of the Evidence.

Those volumes also contain stories about Sayer’s other series detective, wine salesman Montague Egg. Very down to earth with his advice on how salesmen should succeed, his stories are “no-nonsense,” yet imaginative in plotting. I especially enjoyed his information about wine.

I would also suggest that one not be put off by the foppish quality of Lord Peter. I’m not sure why some detectives between the wars, like Wimsey, Reginald Fortune, and the early Albert Campion, were created as silly asses. The fact is that, if given half a chance, they will prove that they are far from effete.

Also, their authors, especially Sayers, are people of intelligence, and they write as if they assume the same about their readers. These days, one feels that many writers are appealing mainly to our emotions or our libidos.

Editorial Comment. I regret that two of the covers shown aren’t nearly as sharp as I’d like them to be. I’ll see if I can’t obtain better images to replace them. To see Marie Michal’s work the way it’s meant to be seen, follow the link in the essay above.

Tue 28 Jul 2009

REVIEWED BY WALTER ALBERT:

Q-PLANES. Columbia Pictures-UK, 1939. Aka Clouds Over Europe (US). Laurence Olivier, Ralph Richardson, Valerie Hobson. Cinematography by Harry Stradling; art direction by Vincent Korda and Frederick Pusey; director: Tim Whelan. Shown at Cinevent 41, Columbus OH, May 2009.

Also known as Clouds Over Europe, this is a dandy espionage thriller, with Ralph Richardson stealing the acting honors from Olivier (a bit grumpy, it seemed to me, although this was probably mostly due to the character he played).

Olivier is an impatient test pilot who keeps being passed over for flights because of his fiery temper, while Richardson is a secret operative, unflappable and prone to off-the-cuff humorous asides, with a sharp intelligence that his cover as a man-about-town conceals.

The program notes made much of Richardson’s character Tony McVane as a dapper precursor of James Bond, although Michael Klossner commented to me that he found him more like the Avengers’ John Steed, with his signature cane and posh outfits.

The production team and cast were all first class, with the director just a year or so away from his co-directing stint on The Thief of Bagdad.

Tue 28 Jul 2009

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[2] Comments

A REVIEW BY DAVID L. VINEYARD:

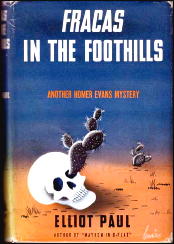

ELLIOT PAUL – Fracas in the Foothills: A Homer Evans Western Mystery and Open Space Adventure. Random House, hardcover, 1940.

“By this time the gangsters had formed an unfortunate relationship with the sheep, and not the one you might think.”

Where to begin …

Perhaps with expatriate American scholar sleuth Homer Evans and his two gun toting girl friend Miriam Leonard (aka Mademoiselle Montana) of Billings, Montana, who has a way with a gun and a classical harpsichord.

Perhaps with the whole insane crew of surrealistic Frenchmen that accompany him in his Parisian adventures: Gonzo the painter; Chief of Detectives Fremont; Dr. Hyacinthe Toudoux, the medical examiner, and his black mistress; a pair of Russian aristocrats turned cab drivers; double-talking lawyer Maitre Francois Ronron; or Moritz the Thinking Dog.

Perhaps with the Indians on the warpath …

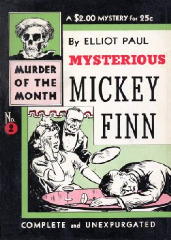

Homer Evans and his crew of surreal Dadaist pals first made their notable debut in The Mysterious Mickey Finn, a phantasmagoric farce of crime and the art world intended as a parody of Philo Vance and S. S. Van Dine.

About two chapters in, that went by the wayside, and the book took off in its own insane direction. In Twentieth Century Crime and Mystery Writers John Ball points out that Van Dine died the same year Mickey Finn was published, “perhaps mercifully.”

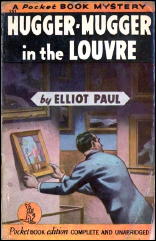

They next appeared in Hugger-Mugger in the Louvre which was more of the same, if arguably madder, especially where it involves the obscure Egyptian pharaoh Tout-or-Nada. Between the two we met the brilliant but somewhat less than sober red-headed van dyke bearded Homer and his Montana born girlfriend who packs a pair of .38’s on their Parisian adventures.

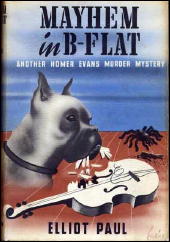

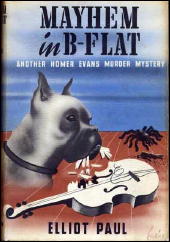

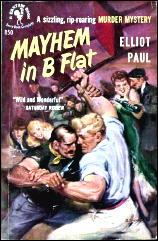

After that they paused for a little Mayhem in B-Flat. There were nine Homer Evans adventures in all, including Waylaid in Boston, I’ll Hate Myself in the Morning, The Black Gardenia, and The Death of Lord Haw Haw.

But everyone has to go home eventually, and in Fracas in the Foothills Homer and Miriam are called back to Montana because there is trouble on the range.

Those nasty old sheepherders represented by the despicable Larkspur Gilligan are threatening Miriam’s Pa Jim and tied with gangsters out of Chicago, as they are informed by Miriam’s childhood friend Blackfoot Rain-No-More (University of California, class of ’29).

Homer decides to sail with her on the Ile de France for home, and so all of their friends pile in to come along with a little careful choreographing of coincidence on Paul’s part — he could hardly leave that crew behind in occupied Paris.

Montana will never be the same.

Neither was mystery fiction.

Paul said of the book in the forward to Mayhem in B Flat:

The next Homer Evans story,

Fracas in the Foothills, brings our group all the way from Paris to the badlands of Montana, where men love horses, and thus the reader who is weary of the European scene will be able to enjoy a good whiff of sage and whatever else there is lying around on the prairies.

Nor does Fracas in the Foothills fail in its promise. If anything it is even more than you could possibly expect. The action takes place in the lower Yellowstone valley of Montana and introduces Blackfoot medicine man Trout Tail III and Blackfoot chief Shot-On-Both-Sides. This is also the book that introduces Moritz.

Gangsters, rustlers, Native Americans, the French, murder (the corpse is scalped), a land grab, arson, a murder trial, rattlesnakes raining from airplanes (twice), the Battle of the Redlands, a stampede, sheep, and more are the ingredients of Paul’s novel.

Admittedly who-dun-it gets a bit lost in the mix, but then that’s true of all of the Evans novels. If you can even remember the outline of the plot by the time you finish, you probably could outwit Homer and his whole crew. It’s a bit like trying to describe the relationship of the plot of a Marx Brothers movie to what actually happens on screen. It isn’t the most rewarding thing you can do.

Fracas in the Foothills may not be Paul’s best, but is certainly his busiest novel. All 451 plus pages of it, including maps.

And not a word is wasted. Though Homer may be feeling a little crowded getting back to the States:

“Was he catching the fever that drove so many of his countrymen to pointless activity?”

Surely not. That would be a tragedy.

Elliot Paul isn’t much read today, Even his best known books Life and Death in a Small Spanish Town and The Last Time I Saw Paris are forgotten.

Only historians of the genre even mention Homer Evans in passing. His other sleuth, Brett Rutledge, is even less well known. It is not right, however. Paul and Homer Evans deserve to be remembered and treasured. The books are not only funny, they are smart, and they are unique.

And as in poor English as it may be, Fracas in the Foothills in the uniquest of them all. Even among the unique it is — unique.

Read it.

But watch out for those rattlesnakes from the sky. That would even shake John Creasey’s infamous flying coyote.

Hopalong Cassidy was never like this.

Them sheepherders never had a chance.

Mon 27 Jul 2009

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[8] Comments

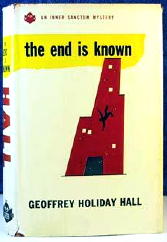

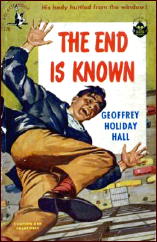

GEOFFREY HOLIDAY HALL – The End Is Known. Simon & Schuster/Inner Sanctum Mystery, hardcover; 1st printing, February 1949. Condensed version appeared in Cosmopolitan magazine, December 1950, as “Who Saw the Man Die.” Pocket #776, paperback; 1st printing, February 1951.

Not a book nor an author I was familiar with when I was recently attracted to it by its cover, and for good reason, I think you might say. Geoffrey Hall wrote only one other mystery, that being The Watcher at the Door (Simon & Schuster, 1954), a spy thriller set in Vienna which got a short notice in Catalogue of Crime by Barzun and Taylor.

In my opinion, though, I think The End Is Known should be far better known than it is. Far from being a spy novel, it’s a mystery that’s strongly in the Cornell Woolrich vein, as darkishly noir as you might want, and in some regards the writing is better than Woolrich’s. Full of strong imagery in the telling, there’s also more than a hint of humor, more than I remember in Woolrich’s.

Of course it’s also time for me to go back and re-read all of Woolrich’s work. It’s been far too long, but in the meantime this singular book by Geoffrey Hall will more than do. I’ve also just discovered that, unknown to Al Hubin, a film has been made from The End Is Known, as an Italian-French co-production called La fine è nota (1993). One comment has been left, so a viewable copy must exist somewhere, and I’d love to be able to see it, wishing as I say that that I also understood Italian.

The title comes from Julius Caesar (the play), in which Brutus at one point says “O, that a man might know / The end of this day’s business ere it come! / But it sufficeth the day will end / And then the end is known.”

Here’s the set-up: As department store vice-president Bayard Paulton makes his way home from work one evening, he is nearly hit by a man falling to his death from an upper story window. The apartment the man came from was his own, remarkably enough, and even more remarkably, Paulton does not know the man.

According to Mrs. Paulton, the man, also unknown to her, came to see her husband, who was delayed and not yet home, and after a few minutes of pacing while he waited, before she realized his intentions, he opened a window and leaped out.

From page 13: “All that occurred to him in that moment, all that he could rember with certainty afterward, was a sentence he had read years before in a novel he had since fogotten. ‘The body fell crazily, and landed askew, like a rag doll.’ And he thought, watching what happened, that was exactly how it looked.”

Thus the other reason for the title. The man’s end is known. Bayard’s mind is quickly taken over by the mystery? Who was he? Why did he tell his wife “Your husband is the only man who can help me?” But then why didn’t he wait for Bayard Paulton to arrive home?

What follows is Bayard’s attempt to trace the man’s life backward and then forward again to learn the answers to these questions and others.

The police, in the form of Lt. Wilson, are interested, but after the body is claimed by an eccentric woman from Montana, who tells them that she only knew him for a few months herself while he was working for her in her diner, they (the police) have other more important things they need to be doing.

The bulk of the book is therefore both fascinating and very talky. Bayard takes out newspaper ads to find people who may have known the dead man, and remarkably enough, he gets responses.

He learns a lot, but not enough to answer his questions. On page 143, he is back in his apartment, alone in his thoughts:

This was the room through which Roy Kearney had wandered during those last minutes of his life; this was the carpet his feet had walked on; here, on this spot where Paulton was standing, here perhaps he had hesitated, motionless, while his mind flipped the coin of decision and watched it come up tails.

If only, Bayard Paulton thought, I had come home five minutes earlier…

On page 173, as Paulton gets closer to the truth, if you don’t mind reading so many quotes, but I do want you to know why I call this a minor unknown classic of noir fiction:

“That was the morning it all happened and everything got wrecked,” Jessie Dermond said. Then she became quite still, even the rocking chair stopped moving. It was clear from her eyes, from her silence, from the quality of her voice before the silence, that that morning, so long before, was a morning she had forced as far into the back of her mind as she could; that was the morning of the day.

Bayard Paulton did not speak. He did not, even, stir in his uncomfortable chair. Because Jesse Dermond’s features, her whole body, were too markedly revealing. They showed pain and sorrow and an incomprehension of the things that life could do to you.

Any novel which begins at the ending, with a death that was inevitable, the final straw in a life of dreams, and the futility of those dreams, has to be noir. For this reason, among those I have already mentioned, as well as still others that I am respectfully refraining from passing along to you, I recommend this book highly.

Mon 27 Jul 2009

DICEY DEERE – The Irish Cairn Murder.

St. Martin’s; reprint paperback, March 2003; hardcover St. Martin’s edition, 2002.

Dicey Deere is a new name to me, and likewise her mystery-solving character, Torrey Tunet, a professional translator by trade, living in Ireland, and by all accounts, a continual thorn in the side of Inspector Egan O’Hare. This is her third case, and the first I’ve had occasion to read.

It also occurred to me that whenever you pick up a new author, one so new that there’s no word of mouth out on him or her yet, there’s always some mental evaluation going on in your mind as you read the first few pages, trying to stay flexible, but weighing one aspect of the story versus another — yes, this is good — no, that wasn’t very well done.

And then there comes a point when suddenly you realize that, yes! this is maybe going to be OK, that the author knows what he or she is doing, and you can sit back and enjoy the rest of the read.

In this book it comes very early on, on page four as a matter of fact, where it’s learned that to keep her linguistic skills in cutting-edge form, Torrey reads a stack of Maigret paperbacks in whatever language she’s going to need to be fluent in next. In this case, it’s Hungarian.

(Note to self: It’s been a long time since I’ve read one of Inspector Maigret’s adventures. It’s time to remedy that.)

As for the mystery itself, the dead man seems to have been a blackmailer, and of course it’s the victim (the blackmailee) who’s the obvious suspect. Torrey is not so sure.

Dicey Deere’s manner of telling the story takes a little time to totally get used to. It’s told in fits and starts, with numerous hints and nuances, jumping sometimes abruptly from one scene to another. Mysterious events are followed by mysterious conversations, with mysterious trips ensuing. John Dickson Carr would have been very proud.

The overall atmosphere is much cheerier and lighter than in any of Carr’s works, I hasten to add. It’s the idea that the reader doesn’t have to be told everything right away that’s the key in this comparison.

(Note to self: It’s been a long time since I’ve read one of Dr. Gideon Fell’s adventures. It’s time to remedy that, too.)

Another stylistic feature I liked is a form of emphasis new to me, though maybe not to you, if you’re been reading different books than I have. I’ll illustrate with a random quote, this one from page 180.

Her look was one of disbelief. She said, “

My fingerprints? I can’t — That can’t be, Inspector! Impossible!” And again, “Im

possible!”

Bibliography: [Expanded from the Revised Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin.]

LA BARRE, HARRIET (ca. 1916- ). Pseudonym: Dicey Deere. Travel writer living in New York City.

Stranger in Vienna. Popular Library pbo, 1986.

The Florentine Win. Walker, hc, 1988; Ivy, pb, 1989.

Blackwood’s Daughter. St. Martin’s, hc, 1990; Ivy, pb, 1992.

DEERE, DICEY. Pseudonym of Harriet La Barre. Series character: Torrey Tunet, in all titles.

The Irish Cottage Murder. St.Martin’s, hc, 1999; pb, June 2000.

The Irish Manor House Murder. St. Martin’s, hc, 2000; pb, August 2001.

The Irish Cairn Murder. St. Martin’s, hc, 2002; pb, March 2003.

The Irish Village Murder. St. Martin’s, hc, 2004; pb, March 2005.

Mon 27 Jul 2009

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review

by Bill Crider:

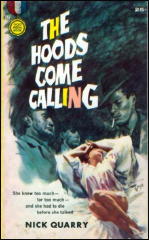

NICK QUARRY – The Hoods Come Calling. Gold Medal 747, paperback original; 1st printing, March 1958. Cover art: Barye Phillips.

Nick Quarry (a great pseudonym) was one of the names used by prolific paperbacker Marvin H. Albert, who also wrote entertaining books as Al Conroy and Tony Rome. Most of the Quarry novels are part of the series featuring Jake Barrow, a tough private eye in the Spillane tradition. The Hoods Come Calling is the first book in the series.

Barrow returns to New York after two years in Chicago, where he has been trying to forget his wife’s infidelities. All he wants from her is the $1600 he left in their joint account, which he plans to use to buy into a private detective agency.

He goes to her apartment to pick up the money, and she shows up drunk. He carries her upstairs and is seen by the neighbors. When he leaves for a minute, she is murdered. Barrow conceals the body, but he is soon being hunted by the police, as well as by his wife’s hoodlum friends. He must prove his innocence by finding the guilty party.

Along the way, there is a bit of 1950s sex (not too graphic) and a considerable amount of violence (which Quarry handles very well). The familiar story has just the right mixture of action and detection to keep things moving along at a rapid clip, and Barrow makes a credible hard guy, though his character seems a bit inconsistent at times.

There is at least one nice surprise in store for the reader; and the ending, in which Barrow proves to be not quite as dishonest as the hoods believe him to be, is quite satisfactory.

Other lively Nick Quarry novels include No Chance in Hell (1960), Till It Hurts (1960), and Some Die Hard (1961).

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

Editorial Note: A few years ago Bill Crider wrote a lengthier article about Marvin Albert, the man behind the Nick Quarry moniker, for the primary Mystery*File website. Follow the link to check it out. Included is a complete bibliography for Albert, including work he did under all of his several pen names.

Mon 27 Jul 2009

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review

by Francis M. Nevins:

MILTON PROPPER – The Family Burial Murders. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1934. Hardcover reprint: Grosset & Dunlap (cover shown).

Milton Propper was born in 1906, graduated from the University of Pennsylvania Law School with honors in 1929, and saw his first detective novel published the same year. He never practiced law but went to work in the mid1930s for the Social Security Administration and continued mystery-writing on the side.

His fourteen whodunits are usually set in Philadelphia and its suburbs and feature young Tommy Rankin, the homicide specialist on that city’s police force.

Propper was far from a paragon of all the literary virtues. He wrote dull prose, peopled his books with nonentities, flaunted like a badge of honor his belief that the police and the powerful are above the law, and refused to play fair with the reader.

Yet paradoxically his best books hold some of the intellectual excitement of the early novels of Ellery Queen. Propper generally begins with the discovery of a body under bizarre circumstances: on an amusement park’s scenic railway in The Strange Disappearance of Mary Young (1929); during a college-fraternity initiation in The Student Fraternity Murder (1932); in a voting booth in The Election Booth Murder (1935).

Then he scatters suspicion among several characters with much to hide, all the while juggling clues and counterplots with dazzling nimbleness. His detectives are gifted with some extraordinary powers — for example, they can make startlingly accurate deductions from a glance at a person’s face — and have no qualms about committing burglary and other crimes while searching for evidence.

Propper novels often involve various forms of mass transportation and complex legal questions over the succession to a large estate. Near the end, having proved all the known suspects innocent, Rankin invariably puts together some as yet unexplained pieces of the puzzle, concludes that the murderer was an avenger from the past who infiltrated the victim’s life in disguise, and launches a breakneck chase to collar the killer before he or she escapes.

Such is the Propper pattern. One of the books in which it shows to best advantage is The Family Burial Murders, whose opening is reminiscent of Ellery Queen’s 1932 classic The Greek Coffin Mystery.

Rankin is summoned to one of Philadelphia’s stately mansions after one body too many turns up at the gravesite during the funeral of a wealthy dowager. The old lady clearly died of natural causes, but her nephew, who also lies in her coffin, was just as clearly murdered, and Rankin’s investigation turns up an assortment of suspects with motive and opportunity.

Propper juggles the legal tangles surrounding the dead woman’s estate with an array of trains, trolleys, elevated lines, and interurban electric trams that give him the crown as mystery fiction’s number one transportation buff.

Unlike his novels, Propper’s life became ever more wretched and messy. He alienated his family, lived in squalor, was picked up for homosexual activity by the police whose lawbreaking he had glorified, eventually lost all markets for his writing and, in 1962, killed himself.

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

Mon 27 Jul 2009

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[5] Comments

THE BACKWARD REVIEWER

William F. Deeck

MILTON PROPPER – The Great Insurance Murders.

Harper & Brothers, hardcover, 1937; Prize Mystery Novels #7, digest-sized paperback reprint, 1943.

While seated on a horse during a polo game, Bruce Clinton is shot in the head by a gunman using a .38 automatic with silencer from “less than 200 feet.” “A neat shot, but not too skillful, after all,” Tommy Rankin, Homicide Squad detective, opines.

Hard man to impress, I’d opine.

“By a system of trial and error, he [Rankin] ultimately cleared up his problems, sometimes even blundering into the answer.” In this novel he is convinced at various times that three separate people were the murderer. Luckily, he does blunder into the answer, leaving profuse loose ends.

Should anyone have an urge to read a Milton Propper mystery, this is probably not the one to choose.

Parenthetically, certain low-level detectives and obvious crooks say “yu,” sometimes, in place of “you.” Could a kindly Philadelphian, since that city is where this novel takes place, explain the difference in pronunciation?

– From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 10, No. 3, Summer 1988.

Next Page »