June 2008

Monthly Archive

Mon 30 Jun 2008

Posted by Steve under

Authors[17] Comments

The following edited excerpt is from

Freelance Odyssey, or “We Don’t Want It Good — We Want It Wednesday”, the unpublished autobiography of W. Ryerson Johnson (1901-1995). Johnny’s remarkable writing career spanned an astonishing eight decades, from his first published short story, “The Squeeze,” in the March 20, 1926 issue of

Adventure, to his last published tale, “No Tinsel, No Humbug,” in the September 1994 issue of

Louis L’Amour Western Magazine.

Pulp western tales were his primary fare, but he also wrote adventure stories, slick magazine stories and articles, men’s magazine stories, mystery novels and short stories, western novels, comic book continuity, and both young adult and children’s books. A partial list of publications to which he contributed: Collier’s, Coronet, This Week, Doc Savage, Phantom Detective, EQMM, and Hustler.

I got to know Johnny fairly well during the last few years of his life. He and his wife visited Marcia and me on several occasions, and we corresponded more or less regularly. We also swapped inscribed copies of various publications; among the ones he sent me are several 20s and 30s western and adventure pulps such as Star Western and Cowboy Stories containing his rangeland novelettes.

When Johnny told me he was writing his autobiography, I asked him if I could read the manuscript in progress and he obliged with a photocopy. Unfortunately it’s a rough draft which he intended to revise but never quite got around to, rambling and speckled with errors and inconsistencies, and with a few missing pages; it would require a considerable amount of editorial work to put it into publishable shape.

Some chapters, however, such as this first installment of one on his relationship with Davis Dresser/Brett Halliday, can be printed with a relatively small amount of editing. A few others will follow as time permits, including those pertaining to his colorful pulp-writing days.

— Bill Pronzini

MEET MIKE SHAYNE – ALIAS DAVE DRESSER [PART ONE]

by W. Ryerson Johnson

Dave Dresser came to town, a fresh breeze blowing out of the West. Breeze? Better say gale. Maybe, hurricane. Known to his readers as Brett Halliday, he wrote the popular hardback series featuring tough Miami private-eye, Mike Shayne.

Dave had my name as chairman of the Pulp Section of the Author’s Guild, and he looked me up at our apartment at 110 East 38th Street. So different in surface ways, we vibed from that first hard hand-clasp and eye-flash contact. I’m low-key; I don’t make waves except as a last resort. Dave would make waves on a sunny-day millpond. He made big waves bigger everywhere.

More than any other series writer I have known, Dave identified with his bigger-than-life storybook character, Michael Shayne. Shayne was lean and spare – a hard-bitten guy addicted to conflict. Tough and turbulent, but coming on amazingly gentle sometimes, sensitive and understanding. Ruggedly honest. As personal as you can get in your reactions to things. Nothing was as act-of-God to Shayne. Everything was an act-of somebody, and if it was a heedless or hostile act, somebody better look out. A direct action man, Shayne stormed around and got things done – if not in one way, then in another.

Same with Dave.

Mike Shayne put away a bottle of Martell cognac a day. So did Dave. They both woke up in the morning chipper as a young robin, head cocked for the dew-fresh worm. (The Martell people sent Dave a case of it one time in appreciation of the promotion he was giving their product in the Shayne novels.)

Volatile was the word for Dave. One time at a party far long in alcoholic liberation I called him that. Volatile. I didn’t think it was a bad word. But Dave glared and hauled his fist back.

“Did anybody ever land one hard on the end of your overhung jaw, Johnny?”

(For the record, he didn’t.)

When I first met Dave, his Michael Shayne was selling millions of copies. Shayne was one of the most successful detective series characters ever launched. And yet it was rejected by 22 publishers. They cited all kinds of reasons, from their opinion that the so-called hard-boiled school of mystery fiction had run its course and was dead, dead, dead, to just plain “unsaleable as written.” (Today, children’s book publishers are quite generally claiming that dinosaur books are “dead” – while teachers and librarians emphatically state they’re the liveliest titles on the racks.)

In November 1951 a new writer’s magazine came out: REPORT TO WRITERS. Dave had an article about his series character in the first issue: “The Hard Times of Michael Shayne.” Before 1936 he had been doing half a dozen romance novels a year for the drugstore circulating-library trade. At $250 a book – no royalties.

Then he wrote his first Shayne manuscript: Dividend on Death. It kicked around for several years before Henry Holt bought it. Holt printed five Shayne titles. None of them sold more than 3000 copies in hardback, with an unimpressive pick-up on a couple of titles in paperback reprint.

Henry Holt bowed out.

Dave pushed the titles around to half a dozen other publishers, and finally Dodd Mead bought. From the time the first Shayne novel appeared, it was a dozen years before it was making much money for anybody.

Now it was roaring – so successful that Dave decided to do his own printing. Dodd Mead, after a lot of filling and hawing, apparently figured that part of the profit was better than no profit, and agreed to continue circulating the series.

Dave put the books together and presented the complete package, jacket and all, to a printer. As I recall, he told me it cost him something like 32 cents to get a copy of the finished book off the presses. They sold in the hardback edition at $2.50. The novels were published under the Torquil imprint.

Torquil was the name of Dave’s dog.

Mon 30 Jun 2008

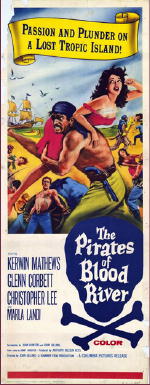

THE PIRATES OF BLOOD RIVER. Hammer Films, 1962. Kerwin Mathews, Christopher Lee, Andrew Keir, Glenn Corbett, Marla Landi, Michael Ripper, Peter Arne, Oliver Reed, Marie Devereux. Screenwriters: John Hunter & John Gilling, based on a story by Jimmy Sangster. Director: John Gilling.

Hammer is known mostly for their horror films, of course, but over the course of the years, they did many other kinds of movies, including noir — I have several on tap to watch, and you’ll see them reviewed here soon enough, I hope — and action-adventure films, such as this one. I even had to create a new category for it, as I’m sure you’ve already have noted.

There’s no “crime” involved in pirate films, per se, except of course, piracy is a crime, and a rather glamorous one at that, movie style. Another small crime of sorts is that this is a pirate film without any boats in it, except stock footage at the beginning and the end, and hardly any water.

Blame this on small, tight budgets that the production people at Hammer had to work under, but worked wonders, they did. There are basically only four sets: the exterior of the tropical village on an island where a group of 17th century Huguenots have settled, fleeing religious persecution; the interior of their primary meeting place; a small jungle surrounding the compound, complete with one river leading to the sea; and a gravel pit doing double duty as a site for a penal colony.

And in spite of financial considerations, the movie is beautifully photographed in color, and populated as if with a cast of thousands, although in reality there may have been perhaps no more than 40 or 50 involved.

Where this island actually is is not explicitly stated, although you (the viewer) are supposed to believe that it is somewhere in the Caribbean and one that has not been discovered by anyone else. Let me get back to river, though, for a minute. Whenever it’s convenient for plot line purposes, the river is filled with hungry, ferocious piranha fish. Piranha fish and quicksand, that’s what I remember of jungle epics when I was a kid. I thought there was going to be quicksand in one scene in this movie, but apparently I was wrong. Too bad. They missed one there.

On to the story line. If there’s a moral to the story, it’s that groups fleeing religious persecution quickly revert to the tactics of their enemies, and quickly become religious zealots themselves. Jonathon Standing (Kerwin Matthews) is the son of one of the village’s board of selectmen (you might say), but that does him no good when he’s convicted of adultery and sentenced to hard labor at the aforementioned penal colony.

From which he eventually escapes, only to land in the hands of Captain LaRoche (Christopher Lee) and his men. Here, taken from the audio commentary for the film, is author Jimmy Sangster‘s original description of the man:

“A strange and fascinating creature, but the fascination is evil. At first glance, he might be called handsome, with his bone structure good. It’s the face of a man without a heart. He has wit and intelligence, and even a sense of humor — but his heart is nothing. The way he moves is so elegant that we may forget he’s a cripple; his hand held close to his body and his hand an upturned claw.”

Sangster, whose voice is one of those we hear, admits that he had Lee in mind for the part from the very beginning. Dressed all in black, with a patch over his left eye, Lee is one of those actors who commands the the viewer’s attention film from the moment we very most see him.

Another moral of the story. Don’t make deals with pirates. They don’t keep their end of the bargain. Never have, never will. I’ve known that ever since I was eight years old. Too bad that Jonathan Standing doesn’t.

The plot could have about as easily served for a good old-fashioned western melodrama, and I shall refrain from saying very much more about it. (Did Hammer Films ever make westerns? Probably not, but if you were to say yes, how surprised would I be? Not very much at all.)

But I do want to mention one highlight of the film for me — a blindfolded swordfight to the death between two of the pirates, played by Peter Arne and Oliver Reed (the latter, as intense as usual, seen above). Whether choreographed or ad lib, it’s completely over the top, and it was worth the price of admission to me right then and there. (Surprisingly enough, the commentators stop talking to watch, but they say nothing as to how it came to be done.)

I’d also like to point out a job well done by Michael Ripper, who plays a henchman named Hench (a nice touch). Ripper usually played bartenders, innkeepers, coachmen and grave robbers in Hammer films. This time it was a much larger part, worthy of his talents, and more — he looks as though he’s enjoying himself immensely.

But is the movie worthy of your time? I enjoyed it, and if you’ve read this far, you very well may too. Vince Keenan tells me that the second movie on this disk, The Devil-Ship Pirates, also with Christopher Lee, is the better of the two. I won’t dispute that, yet. As soon as I feel like watching another pirate movie, I know exactly which one it will be.

Sun 29 Jun 2008

REVIEWED BY WALTER ALBERT:

R. CHETWYND-HAYES – The Psychic Detective. London: Robert Hale, hardcover, 1993.

The psychic detective is Frederica (“Fred”) Masters, a young woman both phenomenally endowed with looks and psychic powers, who hooks up with an occult specialist, who convinces her that he can help her “achieve her potential.” He does, with results that almost destroy both of them, as they venture into twilight zone realms where no sane person goes.

The jacket sports the information that the book is to be a Hammer Film, a promise that was never fulfilled, to my knowledge. It’s just as well, since this is a far-fetched, pseudo-humorous caper that strains the imagination and collapses under its own weight. This won’t go on my short shelf of novels featuring psychic sleuths.

[COMMENT] 06-29-08. R. Chetwynd-Hayes, who was born in 1919 and died in 2001, was a British author and anthologist known best for his ghost stories and tales of “sedate” horror.

Although the two are not identified as series characters in Al Hubin’s Revised Crime Fiction IV, I’ve discovered that Francis St. Clare and his assistant Frederica Masters appeared in eight short stories besides this novel. I’ve not yet been able to identify them all; any assistance would be welcome. —Steve

[UPDATE] 07-13-08. Thanks to Jerry House and the comment he left as a first step in putting a list together of the Francis St. Clare–Frederica Masters short stories.

Doing a little more searching on the Internet, I’ve come up with the following list. John Llewellyn Probert is the person who did the research. All credit goes to him.

“Someone is Dead” in

The Elemental

“The Fundamental Elemental” in

Looking for Something to Suck: The Vampire Stories of RCH.

“The Wailing Waif of Battersea” in

The Night Ghouls

“The Headless Footman of Hadleigh” in

Tales of Fear & Fantasy

“The Gibbering Ghoul of Gomershal” in

The Fantastic World of Kamtellar

“The Astral Invasion” in

Tales from the Dark Lands

“The Phantom Axeman of Carleton Grange” in

Tales from the Haunted House

“The Cringing Couple of Clavering” in

Tales from the Hidden World

Sat 28 Jun 2008

IT’S ABOUT CRIME

by Marvin Lachman

Unredeemed male chauvinists will tell you that woman’s place is in a castle — preferably one depicted with a single light shining. Yet, the Gothic form lends itself to considerably more variety than that. There is the domestic variety in which the setting is an ordinary house, and the heroine’s tribulations have nothing to do with mysterious strangers wandering the moors.

Ursula Curtiss is one of the best writers in this category, and The Menace Within may be the archetypal Curtiss mystery. Heroine Amanda Morley has to contend with:

1. An aunt who has just suffered a stroke.

2. A missing dog.

3. A runaway horse.

4. A jealous boy friend.

5. The care of a neighbor’s two year old baby, a child with a serious vitamin deficiency.

6. A house to care for.

7. Escaped convicts in the area.

Does she also need a psychopathic killer in her bomb shelter? Not really, but without him, we’d only have a soap opera. Instead, we have a slightly unbelievable, fairly exciting book with good descriptions of New Mexico in December.

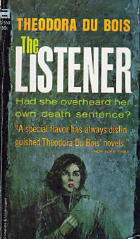

The domestic setting of Theodora Du Bois’ The Listener (1953) is unusual, a convent on New York’s Staten Island. Her heroine, Sister Genevieve, joined the religious order when here fiancé was killed in Greece. Now, still depressed at his loss, she also has a problem of spiritual doubt and, more important for the plot, involvement in a series of crimes related to the tunes played on a woodwind instrument during the night.

Though she wrote more than twenty books, Du Bois is relatively unknown – undeservedly so. She develops The Listener effectively, and her resolution is generally satisfying, though somewhat dependent on coincidence. I’m grateful to her for a well-written book. I’m also grateful to the type-setter for the Ace paperback edition who included this amusing “typo” in a book about the Sisters in a religious order (one of whom is very ugly): “I can see there are some very unattractive angels to this.”

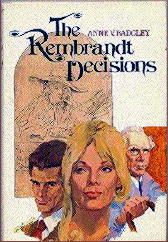

In a promising first novel, The Rembrandt Decisions (1979) by Anne V. Badgley, the author presents a realistic Gothic heroine. Dr. Catherine Gordon, recently widowed at 35 (“recycled by fate”), returns to the labor market to pursue her skill as an art expert. She takes on the cataloging of a valuable print collection and becomes involved with a mysterious Scottish widower whose hobby is said to be installing burglar alarms.

The book begins subtly, and the dialogue between the two protagonists crackles. Unfortunately, the second half is disappointing, depending more on breakneck action than on logic and character development.

Books reviewed or discussed in this installment:

URSULA CURTISS – The Menace Within. Dodd Mead, 1979. Ballantine, pb, 1979.

THEODORE DU BOIS – The Listener. Doubleday Crime Club, 1953. Ace G-550, pb, 1964.

ANNE V. BADGLEY – The Rembrandt Decisions. Dodd Mead, 1979. [This was her only crime novel.]

Sat 28 Jun 2008

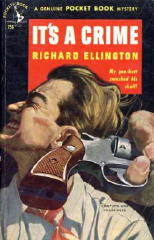

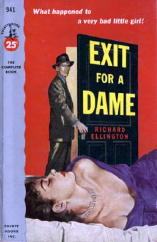

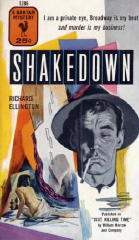

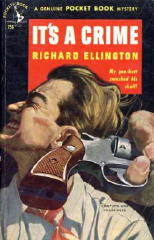

RICHARD ELLINGTON – It’s a Crime. Pocket 756; 1st printing, Dec 1950. Hardcover: William Morrow, 1948.

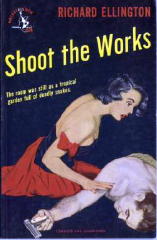

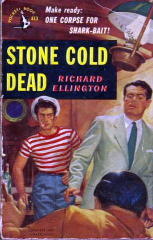

Richard Ellington (1914-1980) wrote only five mysteries, and all five featured a Manhattan-based private eye named Steve Drake. This is the second of them, and for the record, using Al Hubin’s Revised Crime Fiction IV as a basis, here’s a list of all five, along with (eventually) paperback covers for all of them:

Shoot the Works. Morrow, 1948; Pocket #624, 1949.

It’s a Crime. Morrow, 1948; Pocket #756, 1950.

Stone Cold Dead. Morrow, 1950; Pocket #813, 1951.

Exit for a Dame. Morrow, 1951; Pocket #941, 1953.

Just Killing Time. Morrow, 1953; Bantam #1286 as Shakedown, 1955.

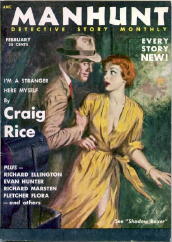

Thanks to the Cook-Miller index to digest mystery magazines, we learn that Ellington also published three short stories in Manhunt and one in Mike Shayne Mystery Magazine:

“Fan Club” Manhunt, April 1953.

“The Ripper” Manhunt, August 1953 .

“Shadow Boxer” Manhunt, February 1954.

“‘Good-By, Cora'” Mike Shayne, February 1968

At least the first of these is a Steve Drake yarn as well. I’m not sure about any of the others. According to the brief biography of Ellington inside the front cover of this paperback edition, he was heavily involved with radio both before and after the war: acting, announcing and writing. What he ended up doing after the career in writing mysteries ended I don’t yet know; perhaps writing for television? (A later search on www.imdb.com turned up nothing.)

The cover of the paperback edition of It’s a Crime will give you an idea of the kind of mystery it is, or if not, at least it’s a portrayal of the one scene that the people at Pocket thought might sell the book. Paul Kresse is the artist, and in the center foreground is the butt end of a gun being grasped by the barrel (only part of the fingers showing) and being used to clout a man in the head. Side view, tie askew, he’s obviously in excruciating pain.

Quoted from the text: “My gun-butt smashed his skull.”

Granted that the scene is in the book, and so is another in close proximity of the same guy with a tommy gun, firing away at Drake before he gets away, only to turn the tables, as shown on the cover, but …

Steve Drake is really only medium-boiled, about 6 or 7 on a standard HB (hard-boiled) scale ranging from 1 to 10. I’ll quote Mr. Drake, who tells his own story, from pages 60-61:

“She was dead, of course. Just the limp position of the arm hanging over the tub told me that. Don’t let anyone kid you. It’s only in very rare cases that you have to listen for heartbeats and feel pulses. They look dead, they don’t look the way they did before. If you don’t believe me, go to the morgue, go to a funeral, go join the police force, wait for the next draft … What the hell am I talking about? Okay, it scared me. It made me jittery. It always does. It would you, too. You might throw up. You might even faint. I didn’t. But then I’m a tough guy.”

Drake actually has two cases in this adventure. The first is a wandering husband caper. The second is a case of blackmail, the victim being the male half of a famous Broadway husband-and-wife duo. That the two cases are connected comes as no surprise to anyone who has read as many mysteries as you and I, but Drake himself takes it in with a slightly perplexed stride.

What is surprising, and it really shouldn’t have been, is that this prime example of lower-echelon tough-guy fiction turns out to have a complex and finely tuned detective story plot to go with it. There are many, many people with access to the dead girl’s apartment, and before her death there were enough of them going in and out that it would take a minute-by-minute timetable to keep it all clear.

After the non-essentials have been eliminated, all of the suspects that remain have iron-clad alibis, and takes a huge effort in deduction on Steve Drake’s art to crack one of them. It’s a plot worthy of Ellery Queen, say, without quite the same finesse — relying on what seems like sheer chance on the part of the killer, and of course the aforementioned coincidence that involves Drake in both cases to begin with.

It’s a neat double combo, in other words, and very much worth seeking out. I’d especially like to locate my copy of the next book in the series. The love affair that Drake seems to find himself in as this one goes along seems to bloom very quickly, and if I read the last couple of pages correctly, Drake proposes marriage and the same time he says he going to be spending the money he made on this case on a trip to St. Thomas. Does she go too, or will she wait for him patiently at home?

These are things an inquiring minds like to know.

— December 2003

[UPDATE] 06-28-08. Prompting my posting this review from the past was an email this morning from SF writer Robert Silverberg:

“Something led me to your web site this morning and an old entry about the forgotten mystery writer Richard Ellington. You ask what he did when he stopped writing mysteries.

“What he did was open a hotel in the Caribbean — perhaps on St. Thomas. (I don’t remember which island, really — it was a long time ago.) I visited it somewhere in the early 1960s and spent a pleasant afternoon exchanging shop talk with him, he talking about mysteries and me about science fiction. As I say, a long time ago, and I have no other details to offer.”

Then from a follow-up email:

“A little googling reveals that he was a delegate to the 1964 Republican convention, representing St. John in the Virgin Islands. Since I visited St. John in that era, that must have been where his hotel was.”

Fri 27 Jun 2008

VICTOR APPLETON – Don Sturdy on the Desert of Mystery, or Autoing in the Land of the Caravans

Grosset & Dunlap; c.1925.

Here’s the first paragraph. Read this and see how you could possibly resist reading on:

“It certainly is a great idea, to cross the Sahara Desert by auto,” remarked Captain Frank Sturdy, as he sat on the shaded veranda of an Algerian hotel and looked out on the shimmering sea of sand stretching away to the horizon.

On the next page:

“Gee, that sounds good to me, Uncle Frank!” broke in Don Sturdy, a tall, muscular boy of fourteen, who had been listening to the discussion. “What a lot of wonderful things a fellow would see on a trip like that!”

And of course off they go, and besides having a fine adventure, there are also a few more tangible goals: to locate the famed Cemetery of the Elephants, to view the fabulous City of Brass, and to find the fantastic Cave of Emeralds.

Not to mention finding missing father of Don’s new friend Brick, who has been kidnapped by natives and is being held for ransom. Their means of transportation out across the desert, as I pictured them, are three early SUV prototypes, equipped with tank treads (and side curtains).

Along the way they encounter numerous dangers: landslides, tarantulas, sandstorms, a band of thieving Arabs and more. It certainly made me feel fourteen again. I read a lot of the early Hardy Boys mysteries when I was a kid, the older thicker ones that belonged to my great-uncle, but never one of the Don Sturdy books, until now. What fun!

But the adult that’s also inside my head found a bit of wonderment at the pacing. On page 209 they are trapped in a cave surrounded by the combined forces of the native kidnappers and the band of Arab thieves. Things indeed look black, as black as they could be.

Not to worry. By page 211 they have escaped, and not only that, they’ve made their way back clear across the desert, and they’re busily making plans for their next adventure. Whoosh! And whoo-wee!

[UPDATE] 06-27-08. Copies in dust jacket are a bit scarce, although certainly not overly expensive ($20 and up on ABE). At any rate, I’ve not been able to come up with a decent one to show you. I think as a young boy I automatically threw the jackets of my books away. So did every other kid, except the smart ones.

Fri 27 Jun 2008

Posted by Steve under

Crime Films1 Comment

Tise originally left the following as a pair of comments to

my previous review on

The League of Gentlemen. The detailed information on the history of post-war British caper films was worthy of its own post, I thought, and so here it is. (And if you’re a film fan and can read this without adding all the movies he mentions to your must-see wish list, you’re a better person than I.) — Steve

The post-war British crime film floated in and out of phases where ex-servicemen are seduced into criminal activity (through a sense of adventure or, more often, the fleeting rewards of black-marketeering and/or corruption by a ‘good time girl’) and, quite often, band together to use their war-time experience to commit crime.

The late 1940s produced such noirish British thrillers as They Made Me a Fugitive (1947; d. Cavalcanti, from the novel A Convict Has Escaped by Jackson Budd), in which Trevor Howard’s down-on-his-luck ex-RAF pilot is drawn into a black marketeering racket; The Flamingo Affair (1947; d. Horace Shepherd) where an ex-Commando captain, infatuated by a femme fatale, agrees to rob his employer’s safe just to keep her in nylons; and in Night Beat (1948; d. Harold Huth) two soldiers returning to civilian life are caught up in black market dealing which inevitably leads to murder.

These films depicted the post-war malaise of returning servicemen trying to readjust to civilian life but, unable to handle various personal disappointments, find themselves sucked into what initially appears an appealing underworld escape. Unlike their U.S. counterpart, at that time, these films were more a case of social commentary than full-blown adventure (such contemporary American films noir as The Blue Dahlia, 1946, and Dead Reckoning, 1947, for example).

Later British films tended to utilise the dependancy on cameraderie of ex-military types. The Intruder (1953; d. Guy Hamilton, from Robin Maugham’s novel Line on Ginger) saw ex-Colonel Jack Hawkins discover his flat being burgled by one of his former troopers, leading to a search through men in the same Army company for psychological/social motives. Lewis Gilbert’s The Good Die Young (1954; from a novel by Richard Macauley) follows four men – an American ex-soldier, an ex-boxer, an American Air Force sergeant who has deserted, and an unscrupulous playboy (a menacing Laurence Harvey) – who plan and carry out an armed mail van robbery. The Ship That Died of Shame (1955; d. Michael Relph and Basil Dearden, based on a novel by Nicholas Monsarrat) brought together a group of ex-Navy men and a wartime motor gunboat to go into the business of cross-Channel smuggling. A thieves-kitchen atmosphere pervaded Tiger in the Smoke (1956; d. Roy Baker, from the story by Margery Allingham) where a gang of war veterans search for their former sergeant who, during a wartime commando raid, deprived them of some hidden loot.

Next to The League of Gentlemen, perhaps the most rewarding of the military-operation type robbery films of this period is Cliff Owen’s suspenseful A Prize of Arms (1962; scripted by Paul Ryder from a story by Nicholas Roeg and Kevin Kavanagh) in which ex-Army officer Stanley Baker and two others pull off (well, nearly) a quarter of a million pounds (£) army payroll robbery. The heightened suspense of the meticulous operation builds and sustains in best ticking-clock fashion.

Fascinating as most of these films are, whether as social observations or caper thrillers, you are quite right, Steve, in observing that the viewers’ edge-of-the-seat experience develops in the unexpected (and unwanted) instances leading to the inevitable downfall. But what an exhilarating journey they lead.

Incidentally, I recently enjoyed The Kill Point (2007), an eight-hour US miniseries taking on the social/psychological angles of a group of ex-Special Forces vets as they sustain a siege following a failed bank robbery. The sub-genre, if indeed it is one, seems to continue quite happily.

A forgotten footnote to the above:

The author of The League of Gentleman, John Boland (who held the post of Chair of the Crime Writers’ Association, 1963-64), also scripted an episode of the long-running and popular Scotland Yard detective drama No Hiding Place (ITV, 1959-67) called ‘The Smoke Boys’ (1963). The episode was tantalisingly described in contemporary TV listings as a baffling series of bank robberies which our regular Scotland Yard detective heroes realise are not committed by any ordinary gang of criminals.

Any ordinary gang of criminals? Could this have been a small-screen reworking of the League …? Perhaps, one day…

Tue 24 Jun 2008

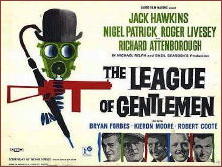

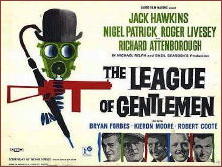

THE LEAGUE OF GENTLEMEN. Allied Film Makers / J. Arthur Rank. 1960. Jack Hawkins, Nigel Patrick, Roger Livesey, Richard Attenborough, Bryan Forbes, Kieron Moore, Terence Alexander, Norman Bird, with Robert Coote, Nanette Newman & Oliver Reed (the latter uncredited). Screenplay: Brian Forbes; based on the novel of the same name by John Boland. Director: Basil Dearden.

THE LEAGUE OF GENTLEMEN. Allied Film Makers / J. Arthur Rank. 1960. Jack Hawkins, Nigel Patrick, Roger Livesey, Richard Attenborough, Bryan Forbes, Kieron Moore, Terence Alexander, Norman Bird, with Robert Coote, Nanette Newman & Oliver Reed (the latter uncredited). Screenplay: Brian Forbes; based on the novel of the same name by John Boland. Director: Basil Dearden.

When this movie was first released in England, it proved to be one of the most popular films of the year. It’s been released there recently as a Special Edition DVD, a long detailed synopsis is available on Wikipedia and an equally in-depth analysis of the film, including its sociological significance re Britain and that country’s post-war malaise, can also be found online.

I’ve also found a two-and-a-half minute trailer on YouTube, which you can go watch if you like, but of course I’ll have something more to say when you come back.

“Heist” films were common in the US in the 1950s — and maybe even before — that is to say, a crime film in which a gang of crooks get together and plan out a robbery in detailed form, sometimes getting away with it and more often not. But apparently this is one of the first British films in the genre, with Jack Hawkins, as Lt.-Col. J. G. Norman Hyde, the ex-military officer in charge.

The others in his squadron of recruits are all down-on-their luck former army officers as well, having been forced out of the service for various wrong-doings and/or squeaking by on the just over the wrong side of the law since entering civilian life. (This aspect of the film gives rise to commentary about post-war Britain and what to do with men like these at variously loose ends with no wars any longer to fight.)

The resulting caper, while entertaining enough, is top-heavy on the front end. There is too much recruitment — with brief glimpses into the players’ current lives, just enough to establish their character (or lack thereof) — and too much preparation for the attack on the bank itself, an act that takes at most only ten minutes in screen time. But “attack” is precisely the right word. These men are fighting back against the establishment — mostly metaphorically speaking, that is, as their eyes are largely on the reward of over a million pounds each.

Here’s another short clip from YouTube, soon after Major Race (Nigel Patrick) has ingratiated his way into becoming Hyde’s second-in-command (with some homosexual implications freely flying, if you’re looking for such things, and I’m not about to go any further than what you see on the screen yourself).

Note that Brian Forbes (who later wrote and directed Seance on a Wet Afternoon, for which he won an MWA Edgar Award in 1965 for Best Foreign Film Screenplay) not only wrote the film but starred in it as well. His wife Nanette Newman (mentioned here once before for his performance in The Wrong Box, produced and directed by Forbes) has a very small role at the beginning of the film, with next to no clothes on (in a bathtub full of suds, I’m sorry to add).

I wish I could say that I was more involved in the film more than I was, but I found the Gentlemen far too seedy, too dishonest, and too corrupt (not all of them and all in different ways) for me to root for them. Waiting and watching for clues as to how their downfall would occur (not if) was, I admit it, a large part of the attraction for me.

The comedy involved — you will find this movie described by some sources as a comedy thriller — is that of the low-key sort of nudge-nudge sort of way that the British so do well, although I wonder if in a crowded theater, several instances of contagious laughter could have broken out, especially back in 1960, when seven men against the establishment was — historians, help me out here — a revolutionary idea still in the making.

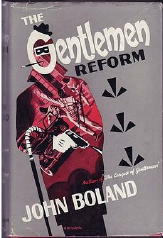

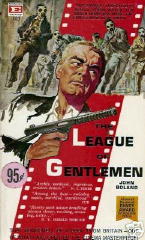

POSTSCRIPT. I see that I have failed to say anything about the book this movie was based on. It was published in 1958 by T.V. Boardman in the UK, with a paperback (I think) from Pan. In the US it was published only by Beacon in 1961, a company otherwise known for its long line of sleazy fiction.

In any edition, though, it’s scarce, and so far I’ve failed to come up for a cover image to show you. The second of the non-YouTube links above states that Boland rewrote the ending of the book after the film came out, thus allowing for two more books in the series: The Gentlemen Reform (Boardman, 1961) and The Gentlemen at Large (Boardman, 1962).

[UPDATE] 06-26-08. Bruce Grossman just emailed me to say that he found a copy of the US paperback edition up for sale on eBay. I’d buy it, but sellers who want money orders and not Paypal just don’t get my money. But here’s the cover. I’ll find another copy one of these days:

Note that this is obviously a movie tie-in edition, with Jack Hawkins’ easily recognizable face front and center.

Mon 23 Jun 2008

REVIEWED BY WALTER ALBERT:

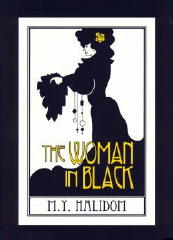

M. Y. HALIDOM – The Woman in Black. Ash-Tree Press, 2007. Introduction by Richard Dalby.

This vampire novel was first published in 1906, and is another in this Canadian publisher’s series of vintage supernatural fiction. “The Woman in Black” is a glamorous seductress, leaving more than broken hearts in her chilling wake. The novel borders, at times, on the edge of parody, but was certainly worth resurrecting, although its audience is undoubtedly a limited one.

The series is often chiefly distinguished by its scholarly introductions. That is certainly the case here, as Richard Dalby traces the life and career of a forgotten writer with his characteristic grace. He does go a bit far, however, in claiming this to be a forgotten “gem.” A gem it may be, but hardly one of great price or quality.

RON WEIGHELL – The Irregular Casebook of Sherlock Holmes. Calabash Press, 2000.

This collection of five Holmes pastiches carries the celebrated detective and his companion and historian Dr. Watson into the realm of the weird and the fantastic, a subject for which Holmes had little patience.

The stories are pleasantly atmospheric but it must be admitted that none of the them produces the authentic chill that Doyle, even as he’s putting to rest the aroma of the supernatural in a story like The Hound of the Baskerville, produces.

A. F. KIDD & RICK KENNETT – No. 472 Cheyne Walk: Carnacki — The Untold Stories. Ash-Tree Press, 2002.

One of the classics of the Victorian & Edwardian fantastic story is William Hope Hodgson’s Carnacki, the Ghost-Finder. The modern writers, A. F. (“Chico”) Kidd and Rick Kennett have revived Hodgson’s scholarly researcher into the outre in a dozen stories that bring together a group of friends with a common interest in the supernatural who, after dinner, settle themselves in comfortable armchairs to listen to their host’s tale of another of the cases in which he has once again laid to rest a supernatural entity or entities.

Such undertakings (the revival of a classic ghost-hunter) are generally doomed to a failure of some proportion but, as such efforts go, this displays some imagination. I would imagine that a solitary reader, regaling himself with a good cigar and a fine brandy, by a winter fire, might have quite a capital time with the stories. I read them under less appropriate circumstances (a hot summer afternoon, the room chilled by air conditioning) and still derived pleasure from their leisurely, willfully archaic style.

Sun 22 Jun 2008

MARY McMULLEN – Welcome to the Grave.

Detective Book Club, hardcover reprint (3-in-1 edition); May 1979. Hardcover first edition: Doubleday Crime Club, 1979. US paperback: Jove, 1989. UK hardcover: Collins Crime Club, 1980. UK paperback: Keyhole Crime, 1981.

It was the second paragraph that hooked me in, line and sinker as well: “Chapter Five was going well. The typewriter seemed to be doing the inventing for him and he was hard put to keep up with it, long square-tipped fingers flying. He was in the middle of what he considered a hilarious sex scene and hardly knowing it he laughed out loud, his shoulders shaking.”

There is a knock on the door. Harley’s wife, who had run off with a gallery owner, has returned. He’d never divorced her, and now he can’t get rid of her. There is a secret, an accident, a dead child, and she is the only one who knows about it.

If ever there was an author proficient in domestic (suburban Connecticut) malice, it was Mary McMullen, who wrote nearly a score of similar mysteries, mostly in the 70s and 80s. There is murder about to happen, and the only questions are: when is he going to do it, is he going to get away with it, and how?

McMullen is also very witty, and she jabs the socio-economic pretensions of the lower corner of the state quite nicely. But she also seems to lose her way after a third of the way through, and she allows Harley’s grandiose plans to fizzle away in a largely mystifying manner. It leads to an unsatisfactory and (upon some reflection) rather unpleasant conclusion.

[UPDATE] 06-22-08. It’s over six years later, and for the life of me, I do not remember either the ending of this book or what I found in it to be displeased about. Either way, I don’t believe there are many authors today who write with the same kind of domestic malice in their books as Mary McMullen did, along with a number of female authors of the 1950s, 60s and 70s, such as Ursula Curtiss, Genevieve Holden, Margaret Millar and others. They didn’t necessarily write noir fiction, but there was a lot of bite to their books.

(Using Ursula Curtiss as an example is a small in-joke, perhaps, since she was Mary McMullen’s sister. See this earlier post for more about their family and the mystery fiction they wrote.)

Next Page »

THE LEAGUE OF GENTLEMEN. Allied Film Makers / J. Arthur Rank. 1960. Jack Hawkins, Nigel Patrick, Roger Livesey, Richard Attenborough, Bryan Forbes, Kieron Moore, Terence Alexander, Norman Bird, with Robert Coote, Nanette Newman & Oliver Reed (the latter uncredited). Screenplay: Brian Forbes; based on the novel of the same name by John Boland. Director: Basil Dearden.

THE LEAGUE OF GENTLEMEN. Allied Film Makers / J. Arthur Rank. 1960. Jack Hawkins, Nigel Patrick, Roger Livesey, Richard Attenborough, Bryan Forbes, Kieron Moore, Terence Alexander, Norman Bird, with Robert Coote, Nanette Newman & Oliver Reed (the latter uncredited). Screenplay: Brian Forbes; based on the novel of the same name by John Boland. Director: Basil Dearden.