Sun 8 Feb 2026

Pulp Stories I’m Reading: NORBERT DAVIS “Walk Across My Grave.”

Posted by Steve under Pulp Fiction , Stories I'm Reading[6] Comments

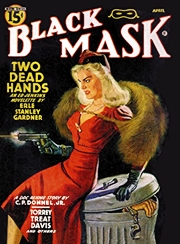

NORBERT DAVIS “Walk Across My Grave.” Short story. First published in Black Mask, April 1942. Reprinted in Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine, November 1953.

I was talking about humorous private eyes after reading Loren D. Estleman’s story “State of Grace” a short while back. The PI in that tale was a chap named Ralph Poteet, a relatively recent hero of sorts based in Detroit. Going back in time, to the early 1940s, the leading character in this story is a chap named Jim Laury, who’s not a PI at all, but a matter-of-fact sort of fellow whose fictional existence was even shorter than Mr. Poteet’s. According to all the evidence I’ve been able to find, this is the only story he was ever in.

He’s a quiet, unprepossessing ,man. Here’s the first couple of paragraphs that was used to describe him as he comes into the story, a two or three pages in:

“He was tall and sleepy-looking and he talked in a slow drawl. He never moved fast unless he had to. He was wearing his long brown overcoat when he entered the funeral parlor through the side door, and he unbuttoned the collar and turned it down, wrinkling his nose distastefully at the heavy lingering odor of wilted flowers that clung to the anteroom.”

Not too much there to stoke anyone’s sense of humor there, I suppose, but I think it’s an excellent piece of writing. No, what I found really funny comes later, speaking of myself in particular, as he listens to his deputy (a man named Waldo) wild and woolly theories about the case, bods thoughtfully as if they had any real bearing about the case, and continues on about business.

Which begins with a figure in black being seen stumbling around in a cemetery at night banging into tombstones and all, then seguing into a murder that has to be solved. Which Mr. Laury does, calmly and in very cool pulpish fashion.

It’s too bad that Norbert Davis never tool the time to wrote down any other of his cases. He wrote lots of other tales equally fun to read, though, in a career that was far too short. He died in 1949, at the age of only 40.