January 2012

Monthly Archive

Tue 31 Jan 2012

A TV Movie Review by MIKE TOONEY:

REHEARSAL FOR MURDER. Made for television. CBS-TV. First broadcast May 28, 1982. Robert Preston (Alex Dennison), Lynn Redgrave (Monica Welles), Patrick Macnee (David Mathews), Lawrence Pressman (Lloyd Andrews), William Russ (Frank Heller), Madolyn Smith (Karen Daniels), Jeff Goldblum (Leo Gibbs), William Daniels (Walter Lamb). Writers: Richard Levinson, William Link. Director: David Greene.

“Unusual form, a mystery. You take the audience by the hand, and you lead them … in the wrong direction. They trust you, and you betray them! All in the name of surprise.”

And it’s likely this movie will surprise you. Of all the productions Levinson and Link did for television, this one comes off as probably their best. While there are several twists in the tale that seemingly come out of nowhere, in retrospect we must admit we were prepared for them with carefully placed clues.

It has been a year since Alex Dennison (Preston) lost the love of his life, Monica Welles (Redgrave). The coroner had ruled her death a suicide, but from the night she died until tonight Alex has had his doubts. He’s convinced it was murder, and he’s determined to catch her killer.

So Alex calls together everyone who was involved in the production in which Monica was appearing on that fateful evening, ostensibly to discuss a new play fresh from his typewriter but in reality to set a trap. Call it, if you will, the Hamlet gambit, a stratagem which several of the suspects tumble to early on:

“Now I get it. Don’t you see what he’s doing?”

“Now that you mention it … no.”

“Hamlet, Act 2, Scene 2, a play within a play to catch his father’s killer: ‘I have heard that guilty creatures sitting at a play, have, by the very cunning of the scene, been struck so to the soul that presently they have proclaimed their malefactions’.”

“‘The play’s the thing wherein I’ll catch the conscience of the king.’ Right?”

Exactly — but to discuss the plot any further would be to spoil the fun. You can watch Rehearsal for Murder on YouTube here — but beware of popup ads!

It almost goes without saying that Richard Levinson and William Link dominated American television crime dramas throughout the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s, either as writers, producers, and/or creators of some of the most fondly remembered programs of the era, among them: 7 Alfred Hitchcock episodes; 3 Burke’s Law; 3 Honey West; Prescription: Murder, the Columbo pilot film, plus 66 more episodes; 194 Mannix; 23 Ellery Queen; several non-series TV movie mysteries, including Murder by Natural Causes and Guilty Conscience; the pilot for Tenafly; and 264 installments of Murder, She Wrote.

You might recognize William Daniels by his speech. He was uncredited as the voice of K.I.T.T., the supercar, in 84 episodes of Knight Rider.

Patrick Macnee will forever be identified with the character of John Steed in 160 episodes of The Avengers, as well as 26 segments of The New Avengers reboot.

Regular TV viewers might remember Lawrence Pressman from 97 episodes of Doogie Howser, M.D.

Tue 31 Jan 2012

FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

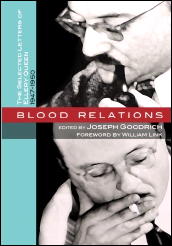

It’s only January but I find it hard to believe that the remaining months of this year will produce a bio-critical book in our genre more fascinating than Blood Relations.

Published by Perfect Crime Books, edited by Joseph Goodrich and with a foreword by master TV mystery series creator William Link, this labor of literary love brings together much of the correspondence between Frederic Dannay and his cousin Manfred B. Lee, the creators of Ellery Queen, between 1947 and 1950 when they lived on opposite coasts.

What a treasure! It’s long been known that Fred and Manny had endless bitter disputes about their work, and Jon L. Breen presented a cross-section of this material in “The Queen Letters†(EQMM, February 2005). Now we have thousands of words more, letters that offer literally a blow-by-blow account of the creation of three of the strongest Queen novels — Ten Days’ Wonder (1948), Cat of Many Tails (1949) and The Origin of Evil (1951).

Even the most knowledgeable Queen fans will be surprised by some of the revelations. With regard to EQMM, Fred (on page 61) boasts to Manny that he’s “done one hell of a lot of rewriting†on the stories he’s published, “including the best of them,†and claims to “have improved many a story, as the original authors have … conceded.â€

Any reader of the magazine who’s wondered about the number of motifs from the EQ novels and stories that are also found in many a story by EQMM contributors now knows the answer: Fred put them there. Manny in turn tells Fred (on page 64) that he has a “tremendous resistance†to the magazine, which he says has been “a vast sore spot with me for years.â€

Among the recurring subjects of their correspondence is their view of the vast differences between them. “I have a drive toward ‘realism,’†Manny writes on January 23, 1950 (page 112), defining the word as “conformity to the facts and color of life and the world as we live in it….â€

He accuses Fred of creating plots “in which vastness and boldness of conception is nearly everything — the colossal idea, planned to stagger if not bowl over the reader. Since such ideas rarely if ever exist in life, they necessarily lead you, in working out the details of the story, into fantasy… [T]he bigger the conception, the more fantastic becomes the story. I then face this plot, with my compulsion toward reality, and the trouble begins.â€

This is 100% consistent with what Manny’s son Rand Lee once heard his father say after a heated phone conversation with Fred: “He gives me the most ridiculous characters to work with and expects me to make them realistic!â€

Personally, I see Fred as spiritual kin to the great Argentinian author Jorge Luis Borges, who was a Queen fan (almost certainly of Fred’s side of the equation rather than Manny’s) and whose stories like “The Garden of Forking Paths†and “Death and the Compass†are set in the same kind of self-contained Cloud Cuckoo Lands as so many of Fred’s plot synopses were.

Manny’s soul brother on the other hand was the character Joel McCrea played in Preston Sturges’ Sullivan’s Travels (1941), a Hollywood director who hates the hit comedies he’s helmed and burns to create a Steinbeck-like “social consciousness†epic called O Brother, Where Art Thou?

If ever there were a real-life Odd Couple, Fred and Manny were it, with the difference that their lacerations of each other aren’t funny. “Why am I writing to you?†Manny asks Fred on November 3, 1948 (page 81). “Why are you writing to me? We are two howling maniacs in a single cell, trying to tear each other to pieces… We ought never to write a word to each other. We ought never to speak. I ought to take what you give me in silence, and you ought to take what I give you in silence, and spit our galls out in the privacy of our cans until someday, mercifully, we both drop dead and end the agony.â€

The miracle is that they managed to stay together, and produce such excellent novels and stories, for so many years.

Or was it a miracle? One of the most surprising aspects of these letters is that side by side with the mutual lacerations are moments when each of these highly sensitive men empathizes with the other in times of personal trouble.

Of all the crosses that Fred was forced to bear, the heaviest was the birth of his son Stephen with brain damage. (He died in 1954, at age six.) “He has been getting insulin injections for about a month…[but] there is hardly any flesh on Steve into which the needle can be plunged,†Fred writes on February 20, 1950, adding that he and his wife “live from day to day, not daring to look ahead to the day after.†(Page 127)

Manny’s reply is dated February 24. “I can only imagine — and that inadequately — what all this is doing to you, this unremitting worry, nervous drain, shock, etc. Keep up your strength. Don’t give up hope. Grit your teeth… This siege on top of what you went through a few years ago would be too much for even the most stable individual. From somewhere you must find the strength to fight it.†(Page 130)

It’s passages like these that illustrate what Fred said after Manny’s death. “We were cousins, but we were closer than brothers.â€

I was privileged to know and work with Fred during the last thirteen years of his life. I would have given much to have known Manny better but he died in 1970 after we had exchanged a handful of letters and met once. What an amazing pair they were!

Mon 30 Jan 2012

YOU CAME ALONG. Paramount Pictures, 1945. Robert Cummings, Lizabeth Scott, Don DeFore, Charles Drake, Julie Bishop, Kim Hunter, Helen Forrest. Co-screenwriter: Ayn Rand. Director: John Farrow.

For some viewers, the primary reason for watching this movie may be the fact that Ayn Rand was in part responsible for the script. Perhaps others couldn’t care less, noting instead that this was the film debut of Lizabeth Scott, known more for her roles in film noir, of which category this movie is most definitely not.

Count me in as one of the latter. The story is kind of silly, and not particularly being a fan of Ayn Rand’s, I don’t know why she was writing movie screenplays in the mid 1940s. You can tell me more in the comments, if you’d care to, but for now, the rest of this review will focus on the movie itself, with no offense intended.

All things considered, though, I’d rather not tell you all that much about the story line, even though every other review of this movie that you’ll find online will probably spell out the whole thing to you, from beginning to end, and in detail.

What I will tell you is it begins as a sort of standard 1940s comedy, with a strait-laced young blonde being assigned to accompany three boisterous, fun-loving and girl-chasing war pilots on a Savings Bond tour across the US.

The blonde being Lizabeth Scott, who soon with a gleam in her eyes turns the table on the hijinks the three decorated aces come up with, and soon thereafter that she is to be seen sitting around their cross-country transport plane with her feet up on the table with the others. Later on she finds the time to sit at a piano and sing a song – and rather well too.

Nature has a way of taking its course in this kind of film, and I might as well tell you that romance does also. This is as much as I will say, except perhaps to add that the three heroes she is hanging out with are hiding a secret, the secret involving… No, I shan’t say, as secrets are meant to be kept.

Or are they? Secrets are what make stories in movies like this churning along, and between you and me, they are also what makes them as sappy and sentimental as the ending of this one turns out to be. I’d also suggest that you keep the tissues handy, but I won’t. If I did, I have a pretty good idea that it would give the whole show away.

If you were to ask me, I’d say you should watch this one for Lizabeth Scott in a role far from the ones her career led her, and for the three buddies she finds herself on the road with. Together they make a very engaging, fun-loving foursome, and like me, you may find yourself enjoying the first half of the film much more than the second.

Mon 30 Jan 2012

A TV Series Review by Michael Shonk

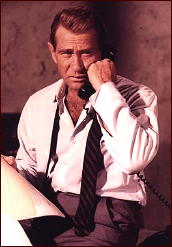

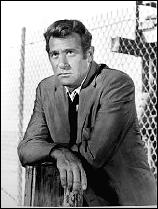

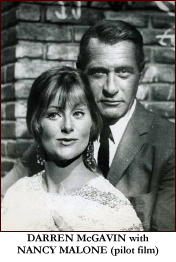

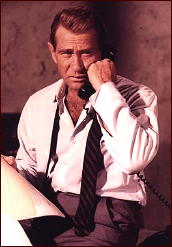

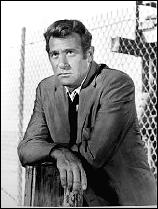

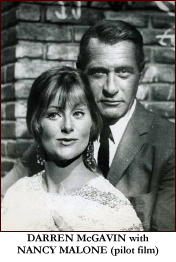

THE OUTSIDER. NBC. 1968-1969. 26 episodes at 60 min each. Universal and Public Arts (* Executive Producer Roy Huggins). Cast: Darren McGavin as David Ross. Theme by Pete Rugalo. Created by John Thomas James (Roy Huggins). Produced by Gene Levitt. (*) Huggins had nothing to do with the series but owned Public Arts so his credit was with the Public Arts Production screen credit. Previously on this blog: A review of the TV Movie pilot The Outsider.

The Outsider tried hard to be loyal to its noir roots but it was born at the wrong time. From Broadcasting (8-19-68) article entitled “1968-69: The Non Violent Seasonâ€:

“Actually no show has had a rougher time of it in the anti-violence climate than the Universal Television–Public Arts Production of The Outsider. It was bought by the network and in production long before the [Bobby] Kennedy assassination.â€

It was August (first episode aired September 18th) and fifteen episodes had been completed, but NBC was still demanding changes. Series producer Gene Levitt commented that they were still redubbing the first eight episodes and had been doing so every day for the last seven weeks.

The article sites an example of the changes. In episode “Love Is Under L,†the original finished scene had the bad guy attack Ross with a knife. Ross flips the guy over a bar counter. The guy rises from behind the bar ready to continue the fight when he realizes his knife is in his chest. He pulls out the knife and dies. The edited scene that made it to the air has the man never rising from behind the bar and Ross’ reaction telling the audience the bad guy was dead.

The first episode was a hit in New York easily winning its Wednesday 10pm time slot with a 43 share. But the reaction was best summed up by Chicago Daily News Dean Gysel, “It is one thing to avoid violence … another to avoid drama.†(Broadcasting, 9/23/68)

While not as well remembered as Roy Huggins, showrunner Gene Levitt also had a long successful career. In 1947 he adapted Raymond Chandler’s stories for the radio series Philip Marlowe starring Gerald Mohr. Most famous for creating Fantasy Island, Levitt’s credits include such shows as Front Page Detective, Maverick, Combat, Alias Smith & Jones, Barnaby Jones, and Hawaii Five-O.

I have recently watched the following episodes:

“One Long-Stemmed American Beauty.†Written by Shirl Hendryx. Directed by Alexander Singer.

Noir tale of life in Hollywood as Ross investigates the death of a former dancer turned bit part player and gigolo. Guest Cast: Judith McConnell as Dorothy, Marie Windsor as Leslie.

“I Can’t Hear You Scream.†Written by Edward J. Lakso. Directed by Alexander Singer.

Noir with a heavy mix of 60’s social injustice has Ross on his own trying to save a black small time criminal from execution. The black cop does not think the criminal is worth saving, the thief’s mother does not trust Ross because he is white, the childhood sweetheart refuses to help, and the current girlfriend is more worried about her Hollywood career. Guest Cast: James Edward as Lt. Wagner, Ena Hartman as Eleanor.

“Tell It Like It Was…And You’re Dead.†Written by Bernard C. Schoefeld. Directed by Alexander Singer.

A lonely forgotten star of burlesque decides to write her memoir. When someone tries to kill her, she hires Ross to find out who wants her silenced. Ross falls deeply in love with the memoir’s ghostwriter (who survives and apparently never mentioned again). Noirish soap opera. Guest Cast: Whitney Blake as Judy, Jackie Coogan as Rusty.

“The Girl From Missouri.†Written by Edward J. Lakso. Directed by Richard Benedict.

Naïve girl is looking for her brother in the evil big city L.A. She plans to reunite him with their dying father back in Missouri. Less noir and more like a Mannix episode. Guest Cast: Mariette Hartley as Mary, Jaye P. Morgan as Ginny.

“A Bowl of Cherries.†Written by Bob and Esther Mitchell. Directed by Michael Caffey.

A friend from prison asks Ross to check on his son. The young hotheaded Latino has fallen in love with his white boss’ son girlfriend. Pure 60’s social injustice plot with noir ending illustrating how close 50’s noir and 60’s social injustice stories were in theme. Guest Cast: John Marley as Jason, Tom Skerritt as Arnie.

“Through a Stained Glass Window.†Written by Ben Masselink. Directed by Charles S. Dubin.

The next to last episode of the series was a comedy. The thief who stole and hid $250,000 is finally out of prison. Ross is hired by the victim to follow the thief and get his money back. Ross is not alone as others have the same idea. On the way Ross encounters a series of eccentric characters right out of an episode of The Avengers. Guest Cast: Ruth McDevitt as Alice, Walter Burke as Fox.

“48-Hr. Mile.†TV movie featuring episodes: “Flipside†and “Service For One.†Produced by Harry Tatelman and Gene Levitt. Written by Rita Lakin & Rick Edelstein and Don Carpenter. Directed by Gene Levitt.

“Flipsideâ€: Janet, a shy prudish woman wants Ross to find and stop her out of control sister Diane. Average psychological drama with a better than average cast. Guest Cast: Carrie Snodgrass as Janet, Michael Strong as Dr. Gaynor.

“Service For Oneâ€: Ross is hired to serve a subpoena to reclusive billionaire Bernard Christie. Ross encounters a woman who has fallen in love with Christie’s alter-ego Harry, and a writer who was ruined by the ruthless rich man. Nice noir ending. Guest Cast: William Windom as Christie, Kathie Browne as Amy.

The two episodes are clumsily linked with added storyline of Ross thinking Diane was another girlfriend of Christie.

“Anatomy of a Crime.†TV Movie featuring episodes “Tell It Like It Was…And You’re Deadâ€(see above) and “There Was A Little Girl.†Written by Bernard C. Schoenfeld and Kay Lenard & Jess Carneol. Directed by Alexander Singer and John Peyser.

“There was a Little Girlâ€: A woman claims her step-daughter is really a rich man’s daughter who was kidnapped 12 years ago and never found. Guest Cast: Joan Blondell as Sadie, Simon Scott as Harrington.

The two episodes were awkwardly joined by a voice over (Ross) explaining the two different clients hired Ross on the same day.

From the episodes I have seen, it is apparent the writers were still exploring who David Ross was. Should he fall in love every week or be a detached professional? Is he an outsider with no friends and live in a dump of an apartment or does he have old friends, wear suit and tie, and live in a typical PI office (no secretary)?

McGavin had his limitations. While he made loser Ross admirable, McGavin was unbelievable as Ross the ladies man.

Levitt and the writers would have fixed those problems with time. But the problem no amount of time could fix was NBC, a network so scared it reportedly didn’t want them to show Ross with a gun. And something had to take up all that time the network edited out of the shows.

Fans interested in what Los Angeles looked like in 1967 will be thrilled with the many long drives through various sections of my favorite city. According to Broadcasting (8/19/69), when the writers failed to find enough filler to make the hour time slot, NBC added Public Service ads. There is nothing better for the pace and tension of a dramatic story than long car rides and more commericals.

In typical noir fashion, The Outsider was doomed to fail.

Recommended website:

Darren McGavin & Kathie Browne McGavin’s Authorized website:

http://www.darrenmcgavin.net/the_outsider.htm

Sun 29 Jan 2012

THE BACKWARD REVIEWER

William F. Deeck

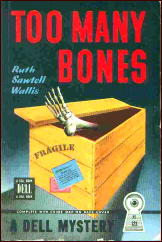

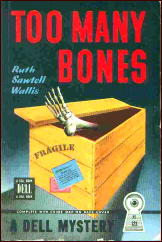

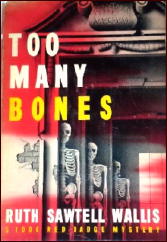

RUTH SAWTELL WALLIS – Too Many Bones. Dodd Mead, hardcover, 1943. Dell #123, mapback, no date stated [1946].

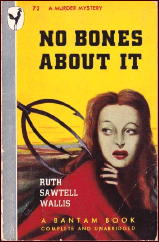

— No Bones About It. Dodd Mead, hardcover, 1944. Bantam #72, paperback, 1946.

The first mystery in Too Many Bones is why the William Henry Proutman Museum, named after the aforesaid gentleman who started the institution to house some Indian relics and his corset exhibit — Proutman manufactured those undergarments at one time — would buy the 600 skeletons in the Holtzman Collection.

Undoubtedly the skeletons were useful for studying a group that had indulged in extensive inbreeding, but why did this obscure museum, in a nearly dead town of 1,200 people, pay $50,000 for them? That is a question Kay Ellis, recently graduated anthropologist, is asked by her instructor before she goes to the museum to assist in cataloging the material. She never provides him with an answer.

Ellis arrives to find that the museum is owned by the relict of Proutman, a still lovely woman between 40 and 50 and for whom the word bitch was invented. She makes life hell for everyone but John Gordon, Ph.D. — him she just makes miserable — the anthropologist in charge of studying the skeletons.

When a death occurs that may be murder with a suicide following it, the sheriff is satisfied that things happened the way they seem. However, some unexplained details rouse Ellis’s curiosity, particularly since she has fallen in love with Gordon. Though she comes to learn too much, she luckily had joined the D.A.R.

This is a competently written non-fair-play mystery with an unusual setting and one of the few hands-on anthropology novels before Aaron J. Elkins’s Gideon Oliver came on the scene.

For reasons best known to herself, Wallis set No Bones About It in 1932. My theory is she did it because the coincidences and a major unlikelihood might have been even less acceptable at a later date.

The Carters, Wests, and Peckhams are, one gathers, a very proud group of families in Weston, Mass., who live in some rather odd houses. The Peckham house, for example, “smelled of owls in the attic and suicides in the cellar. It was not a house you would want to meet on a lonely road at midnight.”

When some of the younger generation return to Weston along with a mysterious movie star, Mattie Peckham, a grasping and unpleasant old lady, begins scattering hints of evil from the past involving the families. As is to be expected, Mattie isn’t around long to continue her nasty ways, she having inhaled a bit too much of the vapors of a cleaning fluid.

What Mattie’s death has to do with a suicide 12 years earlier is cleared up at the end of the book, which some readers may reach. Wallis writes well, but the plot is preposterous.

— From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 12, No. 4, Fall 1990.

Bio-Bibliographic Data: Ruth Sawtell Wallis, when not writing mysteries was (not surprisingly) a well-known archaeologist, with a number of noteworthy accomplishments, which you can read about here, along with a small photo of her.

And of course she did write mysteries. Five in fact:

RUTH SAWTELL WALLIS, 1895-1978. Series character: Eric Lund, in those marked (*).

Too Many Bones. Dodd Mead, 1943.

No Bones About It. Dodd Mead, 1944. (*)

Blood from a Stone. Dodd Mead, 1945.

Cold Bed in the Clay. Dodd Mead, 1947. (*)

Forget My Fate. Dodd Mead, 1950. (*)

Sat 28 Jan 2012

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[9] Comments

ERLE STANLEY GARDNER – The Case of the Troubled Trustee. William Morrow & Co., hardcover, 1965. Pocket, paperback, 1967; many subsequent printings. Ballantine, paperback, April 1995.

If you’d care to know how a mystery writer whose career began back in the 1920s felt about hippies, beatniks and the “love revolution,” look no further. The trustee to a young girl’s estate is in the process of hiring Perry Mason to represent him (page 6):

“At the time of her father’s death, the people with who Desere was running around with had long hair, wore beards, had dirty fingernails, were left-wing idealists, and looked down on her as an heiress. They dipped into her money right and left, patronized her and considered her a square. She went overboard trying to live up to their ideals so they’d respect her. They took her money but always looked on her as an outsider. She’s a sensitive young woman who was hurt, lonely, and eager to be accepted as one of the crowd.”

And so for four years Kerry Dutton has been in charge of what’s called a spendthrift trust for her, but he’s made not a single accounting for it, and all of the investments he’s made using the money are in his name. Which he did for the best of motives. He’s in love with her. Later, on page 12, Perry Mason is discussing the situation with Della, his long-time confidential secretary:

“Sometimes,” Della Street said, choosing her words carefully as though she had rehearsed them, “a woman will be close to a man for a long time, seeing him in the part he has cast for himself and, unless he makes some direct approach, not regarding him as a romantic possibility.”

If Della had any other implications in mind, they seem to have eluded Perry altogether.

Some short while back, I reviewed a book by Gardner’s alter ego A. A. Fair, and if I may quote myself, what I said at the time was that his “strong point was plotting.” That was Kept Women Can’t Quit, which came out in 1960. Here is it five years later in Gardner’s career, and unless I missed something — several somethings, as a matter of fact — the best I can call the plotting is sloppy.

On page 103, a courtroom witness seems to know about the $250,000 Dutton has accrued in his own account, based on the money entrusted to him; yet on page 128, the judge is astonished to have Dutton testify that he had done so, and I don’t even see how the previous witness could possibly have known.

Chapter 17 centers around a witness who claims he heard a shot just before putting on the ten o’clock news, which is not really time enough to help Perry’s client, but somehow Perry thinks it does. And on page 149, when the witness appears in court, he says he heard the shot just before the nine o’clock news. Hamilton Burger jumped to his feet to strike out the testimony, and so did I.

There’s more. On page 93, Perry learns that the murder victim had been at one time briefly questioned about a murder that took place in a rooming house where he was staying, but fortunately he had an alibi. On page 171, it turns out that were a whole series of such rooming house murders, that he had lived in two of them, and that the police had “descended on him like a ton of bricks.”

And if you were to allow me to continue just a little longer, I’d say that there is a huge chew of coincidence still to come, one so large that it takes a couple of sizable gulps and another big swallow to get it down.

It’s all fixable, except for perhaps the latter, and of course you do have to realize that coincidences like this one actually happen. All in all, though, I really think Gardner was coasting with this one, and he was making it up as he went along. And he never went back to tidy up the loose ends.

[UPDATE] 01-28-12. It’s been too long since I wrote this review for me to remember the details, especially those dealing with the points I brought up as examples as poor plotting. I wish I’d been clearer about each of them at the time, when they were still fresh, because to me now, it sounds as though I may have been sounding off on very minor discrepancies.

I don’t think I was, however, so I haven’t edited this review to delete them or change anything I said. If you’re reading a detective novel in which the clues, the timing of events and the testimony of witnesses is important, then so are the details, and that’s the point of my review.

I wrote this rather negative assessment, as I recall, with a great deal of reluctance. Gardner was the first “grown-up” author that I ever read. I still remember being allowed the first time into the adult section of the local library and seeing a The Case of the Lucky Legs on the shelf. I grabbed it, took it home with me, and I thought it was terrific.

As for Gardner’s opinion of the hippie movement, he was 76 at the time, and I might suggest that in the mid-60s no one over 30 understood either the Love Generation or the Sexual Revolution, except for the long hair and scruffy beards.

Sat 28 Jan 2012

IT IS PURELY MY OPINION

Reviews by L. J. Roberts

REED FARREL COLEMAN – Innocent Monster. Tyrus Books, hardcover, November 2010; trade paperback, January 2012.

Genre: Private eye. Leading character: Moe Prager; 6th in series. Setting: New York City.

First Sentence: Katy’s blood was no longer fresh on my hands and after 9/11 people seemed to stop taking notice.

It has been six years since Moe worked his last case; the case that created an estrangement from his daughter, Sarah. When Sarah asks him to find 11-year-old Sashi Bluntstone, an art prodigy who has been missing for three weeks, he can’t refuse her. What he didn’t expect were the dark secrets and betrayals hidden in that world of apparent refinement.

Coleman’s background in philosophy and poetry are clearly reflected in his writing. The story’s opening conveys the mood of the story while providing back-story to new readers. Achieving both, without bogging down the story’s beginning, is only one example of Coleman’s talent.

His style and imagery is one which both tells a good story, but makes you stop and think about what he’s saying… “There are lies to hate and lies to adore. Even now, seeing it clearly maybe for the very first time, Coney Island was a lie I adored.â€

The strong sense of place nearly becomes extra character and the dialogue brings the characters to life. Moe is a character I particularly like. He is not perfect, has known and contributed to tragedy, is definitely not a super-PI, but he is intelligent, determined and has a wry sense of humor.

He has an overriding morality and ethical core along with a certain vulnerability. It is for others who are vulnerable that he does his job; not for the money.

The book is very well plotted and engrossing. Exposing the dark side of the art world is fascinating as is the reminder that we should all “Beware the innocent monster†as the one we don’t suspect is the one who is often most dangerous.

Although there is certainly a case to be resolved, the story is very much about Moe. Many of the issues in his life are, if not resolved, at least confronted, acknowledged and accepted. This feels to be a pivotal book in a series one should read in order from the beginning. I look forward to seeing where the series goes from here.

Rating: Very Good.

The Moe Prager series —

1. Walking the Perfect Square (2001)

2. Redemption Street (2004)

3. The James Deans (2005) [Shamus, Barry, and Anthony awards; nominated for the Edgar, Macavity, and Gumshoe awards]

4. Soul Patch (2007) [Barry and Edgar award nominees]

5. Empty Ever After (2008)

6. Innocent Monster (2010)

7. Hurt Machine (2011)

Fri 27 Jan 2012

REVIEWED BY WALTER ALBERT:

TWO OF A KIND. Columbia, 1951. Edmond O’Brien, Lizabeth Scott, Terry Moore, Alexander Knox, Virginia Brissac, J. M. Kerrigan, Louis Jean Heydt. Director: Henry Levin. Shown at Cinecon 39, Hollywood CA, Aug-Sept 2003.

This was scheduled to showcase Terry Moore, who was interviewed after the film. She’s a garrulous senior citizen now, very up-beat, but in her prime (and the film seems to have caught her in it) she was a busty, perky, sexy but wholesome-looking actress.

This was, indeed, a nifty crime film and may even have had a bit of crackle, much of it due to the cast and the crisp direction of Levin.

Alexander Knox is a shady lawyer, who manages the affairs of a wealthy couple whose only son disappeared many years ago. O’Brien is prepared to be that son and lay claim to their inheritance, while Scott is their partner-in-crime and Moore a ward of the wealthy couple.

O’Brien is first-rate as the good/bad con-man, Knox is appropriately smooth and dissembling as the lawyer and Moore and Scott make an interesting contrast in sexpots.

Editorial Comments: My own review of this film appeared earlier on this blog. Check it out here. A two-minute clip from the movie can be found here on YouTube. It’s the scene in which the three conspirators get together to plan strategies. It’s short, but while Terry Moore is everything that Walter says she is (see the photo above), the clip helps to show why, in my words, “this is Lizabeth Scott’s film all the way.”

Fri 27 Jan 2012

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[2] Comments

REVIEWED BY RAY O’LEARY:

TUCKER COE – Murder Among Children. Random House, hardcover, 1967. Signet P4030, paperback, 1969. Five Star, hardcover, 2000, as by Donald E. Westlake writing as Tucker Coe.

Disgraced, reclusive, ex-cop Mitch Tobin is asked by Robin Kennely, a cousin he didn’t know he had, to talk to a Cop who keeps hanging around a Coffee House she and her friends are trying to make a go of. They don’t know what he’s after, just that he haunts the place like a bad odor.

Mitch refuses at first, but is talked into taking the case by his wife. The next day he goes to the Coffee House and finds Robin coming from her boyfriend’s upstairs apartment, covered in blood and holding a knife.

Upstairs, the Police find Robin’s boyfriend and a black prostitute stabbed to death and arrest Robin for murder. But then another partner in the Coffee House gets killed in a hit-and-run accident, and Mitch reluctantly decides he must go after the real killer.

Hardly a work of groundbreaking originality here, but I found the character of Mitch Tobin, with his psychosymbolic brick wall, fairly interesting. Another point: Coe (Donald Westlake) works a Religious Cult into the plot, and it got me wondering whether one might make a list of PI novels involving weird sects. They seem to be almost as basic a convention as the trenchcoat and fedora.

Previously on this blog:

Don’t Lie to Me, by Tucker Coe. [A 1001 Midnights review by Bill Pronzini.]

Thu 26 Jan 2012

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[16] Comments

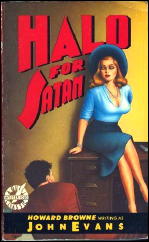

HOWARD BROWNE as JOHN EVANS – Halo for Satan. Quill, paperback, circa 1984. First published as by John Evans: Bobbs-Merrill, hardcover, 1948. Bantam #800, paperback, 1950; Bantam 1729, paperback, 1958.

Over the years there have been mysteries written with the basic premise and understanding that the English language can be used to enhance the pure, unadulterated fun of reading. This is one of them.

Paul Pine is a private eye, and even his client is an eye-opener and an eyebrow-raiser. And what Bishop McManus wants him to do is to track down a man who has offered to sell him a manuscript written, so he says, by Jesus Christ himself. The story goes on from there.

Just before Pine finds the first body, he meets a girl. Page 38:

I listened to the sound of high heels click into silence on the uncarpeted stairs. When there was nothing left but quiet, I lighted a cigarette and thought about Lola North. A slip of a girl who could put a flat-footed cop into his place, and who was probably proud of doing so. Maybe not, though. Maybe she was worrying a little over how easy the victory has been. And then again, maybe my sheriff’s star badge had been about as impressive as a grapefruit.

A lovely girl, Lola North. Enough figure and not too many years and a face that could come back and haunt you and maybe stir your baser emotions. A girl who could turn out to be as pure as an Easter lily or steeped in sin and fail to surprise you either way.

Later, going back into his office, Pine is given a good solid knock on the head. As he comes to, pages 63-64, he finds that there is another woman involved:

I got a shoulder under my eyelids and heaved hard and they slid about halfway before they stuck again. It was like opening cottage windows after a rain. Pain gnawed at the back of head like rats in a granary.

The hunk of ribbon and the smooth red hair were back again, with a face under them I hadn’t noticed before.

It was a face to bring hermits down out of the hills, to fill divorce courts, to make old men read upon hormones. A face that could sell perfume or black lace undies and make kitchen aprons a drug on the market. Good skin under expert make-up to make it look even better. Brown eyes, with a silken sheen to them. Eyes with a careful, still look as though never just sure what the brain behind them was up to. A nose you never quite saw because her full lips kept pulling you away from it. Hair smooth on top and a medium bob in back that was pushed up here and there to make it casually terrific.

And my aching head was supported pleasantly on a cloth-covered length of firm warm flesh that was one of the lady’s thighs.

I said, “I laughed at a scene like this not more than an hour ago. I thought the usher was going to throw me out.”

Her expression said she thought I was out of my head. I would have liked to be, after what had been done to it.

“Are you all right?” It was the kind of voice the rest of her deserved: husky, full-throated, yet subdued.

I said, “How do I know if I’m all right? I think I’ll kind of stand up.”

Later on Lola North begins to tell Pine some of her story. Page 102:

She turned her head to give me a long level stare. “In one way or another,” she said tightly, “I feel it’s largely my fault that my husband’s in trouble. I’m trying to make amends by getting him out of it. That’s why I followed him to Chicago.”

I pushed what was left of my cigarette through the air vent and stretched as much of my frame as the limited space would allow. “Go ahead,” I said wearily, “and tell me. Pour out the words. My spirits are low and my ears are numb, but I’ll listen. Other people read books or go to the fights or walk in the sun or make love. But not poor old Pine. He just sits and listens.”

She said stiffly, “This was your idea. You wanted to know these things,”

“Yeah. Go ahead and tell them to me.”

The next morning, Pine gets back to his office. Page 118:

Nine-thirty was early for me to be at the office, any morning. But I had wakened about eight o’clock, dull-eyed and unhappy, and filled with a vast restlessness that had no answer.

It was a dreary, rain-swept day, raining the kind of rain that comes out of a sky the color and texture of a flophouse sheet and goes on and on. I opened the inner-office window behind its glass ventilator, put my hat and trench coat on the customer’s chair and poked my shoe at the windrows of office junk left on the floor by yesterday’s prowler. The cleaning lady must have taken one look at the wreckage and gone downstairs to quit.

On pages 130-131, Pine is at the home of the second woman:

“Damn you,” she said. And then she laughed. “I’m not through with you yet, mister!”

“What about Myles? Is he as broad-minded as he is rich?”

She shrugged and she wasn’t laughing any more. “The hell with him,” she said recklessly. “I need young men — men with the sap of life in their veins and a good strong back. Myles is too old for me.”

I said, “Another woman said almost the same thing to me last night. What’s the matter with you dames? You make a guy afraid of reaching his forties.”

Later, after sitting around in his office with nothing happening for several hours, Pine starts to leave. Page 139:

By eight-thirty I had all I could take. I had gone through everything in the paper except the want ads, there was a mound of cigarette butts in the ashtray, and my tongue tasted like something rejected by a scavenger. I glowered at my wrist watch, growled “Up the creek, brother!” for no reason at all and put on my trench coat and hat.

The fat little dentist in the next office was locking his door for the day as I came out into the corridor. He nodded to me. “Good evening, Mr. Pine. You’re later than usual.”

“And all for nothing,” I said. “I nearly came in to have you drill one of my teeth. Just for something to do.”

His smile was a little sad in a dignified way. “I could have used the business, sir.”

Back in his office a little while later, on page 169:

I dug out the McGivern mystery novel it finished it over half a pack of cigarettes. The women in it were beautiful and the private eye was brilliant. I would have like to be brilliant, too. I would even have liked to be reasonably intelligent. I put the book away.

There is twist upon twist in the story that surrounds all these quotes, not all of them believable in the cold, clear eye of dawn, but they will make you sit up and take notice. Guaranteed.

— September 2003

Note: The cover of the first Bantam paperback was “covered” earlier here on this blog.

Next Page »