Tue 31 Jan 2012

Mike Nevins on BLOOD RELATIONS: FREDERIC DANNAY & MANFRED B. LEE.

Posted by Steve under Authors , Columns , Reference works / Biographies , Reviews[7] Comments

by Francis M. Nevins

It’s only January but I find it hard to believe that the remaining months of this year will produce a bio-critical book in our genre more fascinating than Blood Relations.

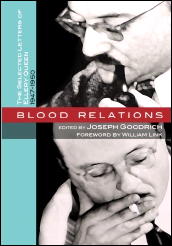

Published by Perfect Crime Books, edited by Joseph Goodrich and with a foreword by master TV mystery series creator William Link, this labor of literary love brings together much of the correspondence between Frederic Dannay and his cousin Manfred B. Lee, the creators of Ellery Queen, between 1947 and 1950 when they lived on opposite coasts.

What a treasure! It’s long been known that Fred and Manny had endless bitter disputes about their work, and Jon L. Breen presented a cross-section of this material in “The Queen Letters†(EQMM, February 2005). Now we have thousands of words more, letters that offer literally a blow-by-blow account of the creation of three of the strongest Queen novels — Ten Days’ Wonder (1948), Cat of Many Tails (1949) and The Origin of Evil (1951).

Even the most knowledgeable Queen fans will be surprised by some of the revelations. With regard to EQMM, Fred (on page 61) boasts to Manny that he’s “done one hell of a lot of rewriting†on the stories he’s published, “including the best of them,†and claims to “have improved many a story, as the original authors have … conceded.â€

Any reader of the magazine who’s wondered about the number of motifs from the EQ novels and stories that are also found in many a story by EQMM contributors now knows the answer: Fred put them there. Manny in turn tells Fred (on page 64) that he has a “tremendous resistance†to the magazine, which he says has been “a vast sore spot with me for years.â€

Among the recurring subjects of their correspondence is their view of the vast differences between them. “I have a drive toward ‘realism,’†Manny writes on January 23, 1950 (page 112), defining the word as “conformity to the facts and color of life and the world as we live in it….â€

He accuses Fred of creating plots “in which vastness and boldness of conception is nearly everything — the colossal idea, planned to stagger if not bowl over the reader. Since such ideas rarely if ever exist in life, they necessarily lead you, in working out the details of the story, into fantasy… [T]he bigger the conception, the more fantastic becomes the story. I then face this plot, with my compulsion toward reality, and the trouble begins.â€

This is 100% consistent with what Manny’s son Rand Lee once heard his father say after a heated phone conversation with Fred: “He gives me the most ridiculous characters to work with and expects me to make them realistic!â€

Personally, I see Fred as spiritual kin to the great Argentinian author Jorge Luis Borges, who was a Queen fan (almost certainly of Fred’s side of the equation rather than Manny’s) and whose stories like “The Garden of Forking Paths†and “Death and the Compass†are set in the same kind of self-contained Cloud Cuckoo Lands as so many of Fred’s plot synopses were.

Manny’s soul brother on the other hand was the character Joel McCrea played in Preston Sturges’ Sullivan’s Travels (1941), a Hollywood director who hates the hit comedies he’s helmed and burns to create a Steinbeck-like “social consciousness†epic called O Brother, Where Art Thou?

If ever there were a real-life Odd Couple, Fred and Manny were it, with the difference that their lacerations of each other aren’t funny. “Why am I writing to you?†Manny asks Fred on November 3, 1948 (page 81). “Why are you writing to me? We are two howling maniacs in a single cell, trying to tear each other to pieces… We ought never to write a word to each other. We ought never to speak. I ought to take what you give me in silence, and you ought to take what I give you in silence, and spit our galls out in the privacy of our cans until someday, mercifully, we both drop dead and end the agony.â€

The miracle is that they managed to stay together, and produce such excellent novels and stories, for so many years.

Or was it a miracle? One of the most surprising aspects of these letters is that side by side with the mutual lacerations are moments when each of these highly sensitive men empathizes with the other in times of personal trouble.

Of all the crosses that Fred was forced to bear, the heaviest was the birth of his son Stephen with brain damage. (He died in 1954, at age six.) “He has been getting insulin injections for about a month…[but] there is hardly any flesh on Steve into which the needle can be plunged,†Fred writes on February 20, 1950, adding that he and his wife “live from day to day, not daring to look ahead to the day after.†(Page 127)

Manny’s reply is dated February 24. “I can only imagine — and that inadequately — what all this is doing to you, this unremitting worry, nervous drain, shock, etc. Keep up your strength. Don’t give up hope. Grit your teeth… This siege on top of what you went through a few years ago would be too much for even the most stable individual. From somewhere you must find the strength to fight it.†(Page 130)

It’s passages like these that illustrate what Fred said after Manny’s death. “We were cousins, but we were closer than brothers.â€

I was privileged to know and work with Fred during the last thirteen years of his life. I would have given much to have known Manny better but he died in 1970 after we had exchanged a handful of letters and met once. What an amazing pair they were!

January 31st, 2012 at 1:48 pm

I buy just about all the mystery related reference books and will have to get this also. Hopefully there will be many letters discussing the operation of ELLERY QUEEN MYSTERY MAGAZINE.

January 31st, 2012 at 2:31 pm

I’ll second the motion. It’s in my Amazon cart right now.

January 31st, 2012 at 7:07 pm

I think I’m with Dannay!

What an essential book. $14.95 is an amazing price too. Any other genre history they do?

January 31st, 2012 at 7:17 pm

Here’s the link to their website:

http://www.perfectcrimebooks.com/

I don’t see any other mystery reference type books. They’re heavy so far into PI fiction, both reprint and new, and story collections, which I like to see.

February 4th, 2012 at 11:10 am

Fascinating review. Sounds like an absolute must-read.

March 22nd, 2012 at 6:59 am

Like many Queen fans I’ve always wanted to know more about how Dannay and Lee actually went about producing their books (in the same way that some would like to know what was Lennon’s, what Macartney’s input into a great Beatles song). I shall be particularly fascinated to learn of the genesis and production of Ten Days’ Wonder, for me the greatest, the most perfectly achieved detective story ever.

April 6th, 2012 at 10:57 am

I’ve finished reading the book, and it is as impressive as Mike suggests. Besides the actual collaboration, the comments about the need for money, for instance, are also very interesting–Lee lived marginally financially. The religious differences between the cousins also come into the book in a minor way. Although the Jewish backgrounds of the cousins has been known for a long time, Dannay turns out to be a practicing Jew, unlike Lee. But, of course, the big story is the details of the emotional collaboration.