June 2014

Monthly Archive

Mon 30 Jun 2014

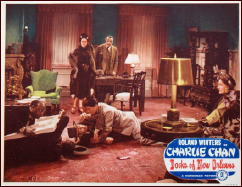

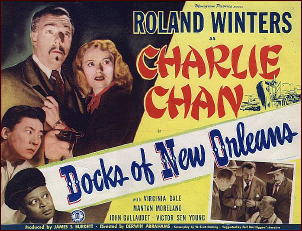

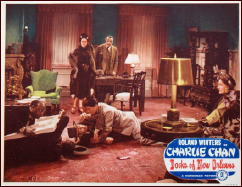

DOCKS OF NEW ORLEANS. Monogram, 1948. Roland Winters (Charlie Chan), Virginia Dale, Mantan Moreland (Birmingham Brown), John Gallaudet, Victor Sen Young (Tommy Chan), Carol Forman, Douglas Fowley, Harry Hayden, Howard Negley, Stanley Andrews, Emmett Vogan, Boyd Irwin, Rory Mallinson. Based on characters created by Earl Derr Biggers. Director: Derwin Abrahams.

That’s quite a list of actors above, and you may or may not be surprised to learn that each and every one has a essential role to play in this, the second of Roland Winters’ attempts to play Charlie Chan in the movies. He’s full of the usual parables and platitudes, maybe even more than usual, and his facial makeup is fine, but his delivery lacks any sense of urgency, to put it mildly.

In fact, the whole affair seems dull and flat to me, with only an occasional twinkle in Charlie’s eye as he goes about his business of investigating the mysterious murders of three members of a small syndicate of chemical manufacturers, bound together by a contract that leaves control of the syndicate to any survivors, in case of the sudden death of any one of them.

There is also a disgruntled chemist who is shoved aside when his newly discovered formula proves to be valuable, and a gang of spies who don’t want certain chemicals to be sent to South America and the opposition to the forces they are working for. Plus, taking a deep breath, the niece and the new assistant to the first man to die may not be be wholly innocent of wrongdoing.

So you do need a scorecard to keep everyone straight. Without one, it may prove difficult to figure out who did what and when to to whom, let alone why, but it can be done. Strangely enough, there is so much story crammed into the running time of 64 minutes that there is very little left for the usual antics and byplay of Birmingham Brown and number two son Jimmy. Except, of course, for the crucial scene in which the means of the murders is uncovered.

Which perhaps comes too soon in the movie to suit anyone such as I who would have liked the mystery, something like a locked room affair, but not quite, to have stayed on the front burner longer. Even with the large array of suspects at hand, I don’t think the identity of the actual killer will come as much of a surprise to anyone reading this, but sometimes it feels good to be proven right when you watch a movie like this one.

Mon 30 Jun 2014

Posted by Steve under

Reviews1 Comment

THE ARMCHAIR REVIEWER

Allen J. Hubin

JOHN le CARRÉ – The Russia House. Alfred A. Knopf, hardcover, 1989; Bantam, paperback, 19890. First published by Hodder & Stoughton, UK, hardcover, 1989. Film: MGM, 1990 (Sean Connery, Michelle Pfeiffer).

The latest John le Carré tale, The Russia House, departs from the Smiley oeuvre but otherwise is in the usual le Carré vein. Nothing much happens in 353 pages, but the language is elegantly expressive, the principal character is beautifully rendered, the workings of the intelligence agencies (U.S. and British) are recounted with surgically satiric precision, and what moves the hearts of people is most poignantly expressed.

A manuscript of a novel, apparently penned by a Russian physicist, comes to failing London publisher Barley Blair via Katya, a woman associated with a Moscow book agency. And via British Intelligence, which intercepts the manuscript when Barley is missing — out drinking and womanizing, as usual — at the critical time.

The Intelligence boffins are in a gentlemanly frenzy over what the “novel” says about Soviet military capability and want Barley to go over and milk the physicist of every smidgen he contains. The Americans, whose frenzy is never gentlemanly, also come to have a part in the proceedings.

Strange what tools come to hand in the spying game; stranger still what their use may lead to….

— Reprinted from The MYSTERY FANcier,

Vol. 11, No. 3, Summer 1989.

Editorial Comment: For my review of the film, go here.

Mon 30 Jun 2014

Reviewed by DAVID VINEYARD:

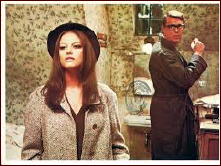

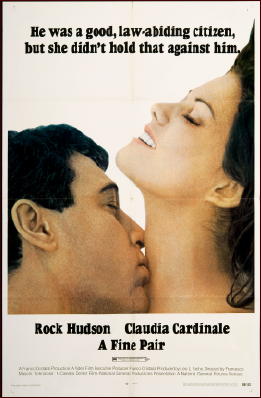

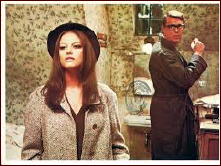

A FINE PAIR. National General Pictures, 1969. First released in Italy as Ruba al prossimo tuo (1968). Rock Hudson, Claudia Cardinale, Leon Askin, Ellen Corby. Tony Lo Bianco. Score by Ennio Morricone. Directed by Francesco Masselli.

Taxi driver carrying Esmerelda Marini (Claudia Cardinale) into New York: Over there is the United Nations building.

Esmerelda: I can see they aren’t getting anything done from here.

Sadly that is the best line in this rather strained caper comedy that never quite lives up to the jaunty Ennio Morricone score.

Rock Hudson is dour police Captain Mike Harmon, a pain in everyone’s ass, who was close to Esmerelda’s policeman father with young Esmerelda having a schoolgirl crush on him that has carried over to the present day.

It’s not a match made in heaven though, Esmerelda is a rebel and jewel thief.

She wants Hudson to help her return the jewels she stole in Austria from a wealthy American’s villa and he reluctantly agrees (all too easily).

Of course she is breezy, fun, amoral, smart, sexy, and only half clothed most of the time so it is natural the stiff cold Captain is going to melt — almost literally when he has to get the villa they are robbing to 194 degrees to disable the alarm and she holds the place up in nothing but wet bra and panties.

Nor does he suspect he returned paste jewels while she stole the real ones — again.

By the time he finds out she has to return more jewels in Rome, he is hooked on her and crime, and they have a big row when she decides to turn hones,t so Mike pulls off the heist and frames her having her own uncle arrest her so she can’t leave.

After a narrow squeak the two end up happily together.

And it just ends.

One thing, with Rock in black framed glasses you now know how he would look as Clark Kent or Rip Kirby.

This light film would like to be something along the lines of A Man and A Woman, with an infectious score, flashy photography, and a naturalistic look. The problem is Francesco Masselli is a heavy-handed and unimaginative director, Hudson doesn’t seem comfortable with his character for the first half of the film, and while Cardinale is gorgeous and fun, she makes no sense as a character.

Had they done this a few years earlier as one of those slick Universal films Hudson was so ubiquitous in from the late fifties through the mid-sixties, it might have been the light playful romantic comedy caper it was meant to be, but this is just a bore.

Cardinale is beautiful, funny, sexy, and screwball, the scenery is lovely, and the two actors have some chemistry once Hudson is able to move into a more familiar mode, but it’s a highly unsatisfying film otherwise.

I missed it the on its initial release and it has taken until now to see it. I wish now I had waited another couple of decades.

Not bad so much as ho, hum.

Sun 29 Jun 2014

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[4] Comments

THE BACKWARD REVIEWER

William F. Deeck

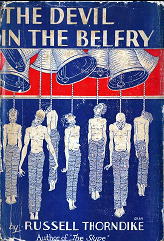

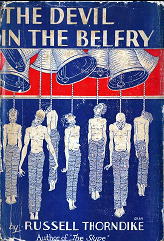

RUSSELL THORNDYKE – The Devil in the Belfry. Dial Press, UK, hardcover, 1932. First published in the UK: Butterworth, hardcover, 1931, as Herod’s Peal.

It’s bad enough that Brigadier-General Sir Lionel Hansaw has received a threatening letter from someone he claims is a Hindu. In the mistaken belief that he is a good judge of men, he hires former Captain John Carfax as his bodyguard. While Carfax is neglecting his duty and viewing and listening to a bell-ringing session with the general’s niece, the general is shot dead in his study by a tall Hindu.

The peal being rung as the general died was Herod’s Peal, banned by the Roman Catholic Church many years before. Ringing the peal were the Bede Bell-ringers, nine erstwhile convicts led by the Reverend Lord Upnor, a fanatic on campanology. As Lord Upnor’s group travels about, they continue to employ Herod’s Peal, and each time it is rung, someone is murdered.

Carfax, wishing to find the general’s murderer since he did nothing to prevent the crime, aids Scotland Yard detective Macready in the investigation, if it can be called that, of the various deaths.

In my review of Thorndike’s The Slype, which you can find here, I criticized the plot. I can’t in this novel, for it is a good one. But the characterization and description that made The Slype so enjoyable is totally missing here, though the setting is the same. That marvelous policeman, Sergeant Wurren, appears only briefly, a total waste of a wonderful character. Thorndike tries to do something with Winning, the bell-ringers’ advance man, but it’s not enough.

For campanology addicts like Lord Upnor.

— From

The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 13, No. 2, Spring 1991.

Sun 29 Jun 2014

THE UTAH KID. Tiffany Productions, 1930. Rex Lease, Dorothy Sebastian, Tom Santschi, Mary Carr, Walter Miller, Lafe McKee, Boris Karloff. Director: Richard Thorpe.

The movie begins with a sheriff’s posse hard on the trail of a single man on horseback. He’s young and clean-cut, a good looking fellow with a smart horse, so how could he be an outlaw? The young fellow is Cal Reynolds (Rex Lease), and looks to the contrary, he’s definitely on the wrong side of the law, since as it turns out, the safe haven he’s heading for is a place called Robbers’ Roost.

Thanks to the overall dull minds of the posse after him, he makes it safely. Now Robbers’ Roost is exactly the kind of place you’d expect it to be, given the name, and the fellow in charge is called Butch (Tom Santschi) and the one who appears to be the second-in-command is Baxter (Boris Karloff, and the only reason this old western movie is in any kind of demand today; rumor has it that there may be only one surviving print).

Also on hand is Parson Joe (Lafe McKee), an elderly gentleman who is not allowed to leave, else he may reveal the outlaws’ hideout to the authorities, so he has decided to stay on willingly. Where else could he find so many sinners whose souls he might save? Found by Baxter wandering around the vicinity (no other explanation given) is a young girl named Jennie Lee (Dorothy Sebastian). To save her from being killed, or worse, young Cal claims that she is his fiancée, and (gulp) is forced to marry her on the spot, thanks to the presence of Pastor Joe.

What young Cal does not know is that Jennie is engaged to the local sheriff (Walter Miller), which puts him in quite a predicament – and she as well, as it is clear that she is falling for young Cal, and hence the rationale for quite an entertaining western, believe it or not. There are no singing cowboys, no stupid sidekicks, only a small but incisive love story that probably needn’t have taken place in the West, only this one did.

As for Boris Karloff, although his role is brief, he is a joy to watch and listen to. His voice is as mellifluous as you’d expect it to be, even in this very early talkie, and his body language is certainly more expressive than it needed to be, in this otherwise undemanding role of the second in command of a fourth rate gang of robbers and thieves.

He was an actor with a future (second sight is wonderful), while Rex Lease, as it turned out, as young and handsome as he was, ended up with far less of a career than Mr. Karloff’s.

Sat 28 Jun 2014

Reviewed by JONATHAN LEWIS:

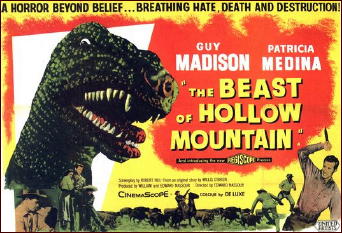

THE BEAST OF HOLLOW MOUNTAIN. United Artists, 1956. Guy Madison, Patricia Medina, Carlos Rivas, Mario Navarro, Pascual GarcÃa Peña, Eduardo Noriega, Julio Villarreal, Lupe Carriles. Directors: Edward Nassour & Ismael RodrÃguez.

Imagine you’re watching an average B-Western about a goodhearted rancher from Texas in both a business and romantic rivalry with a mean-spirited rancher from Mexico. The movie is in color; the acting by Guy Madison and Patricia Medina isn’t all that bad; and the foreboding Mexican landscape is well integrated into the storyline.

So you keep watching. Somewhat entertained, somewhat bored, and now and again remembering the film was billed as a creature feature. Then nearly an hour into the film, a giant, deeply angry stop-motion T-Rex (a fairly impressive special effects achievement considering the film is from 1956) makes its way out of the local swamp and wreaks all sorts of havoc on cows and humans alike.

That’s The Beast of Hollow Mountain for you. Based on a story idea by King Kong special effects innovator, Willis O’Brien, it’s all good fun. While not a particularly great film, the mid-fifties movie is actually quite entertaining provided you go into it with the right mindset.

The last twenty minutes or so, when the T. Rex finally emerges from its mountain hideaway, make up for the fact that you had to wait an entire hour to see the creature. This too long a delay really does make the film significantly less compelling than it could have been.

But getting back to the dinosaur. What a creature! The giant feet making an impression in the mud, the giant teeth and red tongue, and eyes that convey anger. It’s a far more impressive movie dinosaur than the one that appeared in The Giant Behemoth, which I reviewed here. That said, at least in that particular film, we actually got an impressive political backstory as to why the dinosaur decided to stomp all over London. In The Beast of Hollow Mountain, all we really know is that local legend held that there is a – you guessed it, a monster – in the mountain.

There are some fairly harrowing moments, such as when the dinosaur claws at — and peers into — the roof of a shack where two would-be victims are cowering, and when protagonist Jimmy Ryan (Madison) swings back and forth on a rope hanging from a limb of a tree, luring the dim-witted dinosaur to its swampy doom. And listen for the birdsongs. Whether they were deliberately recorded or whether they were merely picked up during filming doesn’t much matter. They really help establish an atmospheric setting for the world’s first, and dare I say, preeminent, dinosaur western film.

Sat 28 Jun 2014

SMALL GENRE DEPARTMENT

by Marvin Lachman

Everyone knows the major divisions of the mystery: the private eye, the classic puzzle, the police procedural, et al. I like small genres, which I define as at least two mysteries about one topic, usually an obscure one. Here are some examples:

1. Mysteries about black-eyed blondes. In the Anthony Abbot book About the Murder of a Man Afraid of Women discussed here, Colt is drawn into the mystery when his fiancee sends him a young blonds with a problem-and a shiner. There was also the 1944 Erie Stanley Gardner novel, The Case of the Black-Eyed Blonde.

2. Mysteries about beautiful women who have documents tattooed on their backs. The only novel which comes to mind is H. Rider Haggard’s Mr. Meeson’s Will (1888), in which the heroine has a will tattooed on her back. In the movies, Myrna Loy had plans on her back in Stamboul Quest (1934) and so did Paulette Goddard in The Lady Has Plans (1942), My favorite variation on this is in the Helen Simpson short story, “A Posteriori,” in EQMM, September 1954.

3. Murders observed by people on trains. I’m sure there are more than the two examples which come to my mind: Agatha Christie’s 1957 Miss Marple novel, What Mrs. McGillicuddy Saw (in Britain as The 4.50 from Paddington), and Cornell Woolrich’s novelette, “Death in the Air” (Detective Fiction Weekly, Oct. 10, 1936), in which the hero sees two people struggling in a tenement, one of whom shoots someone in the elevated car in which he is riding.

4. Mysteries in which the detective is named Paul Pry. Erie Stanley Gardner had a pulp sleuth named Paul Pry, and the hero of Margaret Millar’s first three books was a psychiatrist, Paul Prye. The hero of Albert Borowitz’s This Club Frowns on Murder (1990) is true-crime historian Paul Prye.

5. Mysteries with plots based on the Ted Kennedy Chappaquiddick affair:

a. Warren Adler’s Options (1974), published in paperback as Waters of Decision.

b. Douglas Kiker’s Death at the Cut (1988).

c. Margaret Truman’s Murder at the Kennedy Center (1989).

6. Mysteries about bag people used as couriers for drugs or drug money:

a. Dorothy Salisbury Davis’s Julie Hayes series.

b. Anna Porter’s Judith Hayes series.

7.Mysteries set at the Isabella Gardner Museum in Boston:

a. Jane Langton’s Murder at the Gardner (1988).

b. Charlotte MacLeod’s The Palace Guard (1981). (Madam Wilkins’s Palazzo seems based on the Gardner.)

8. Mysteries with reporter-detectives named J. Hayes:

a. Dorothy Salisbury Davis’s Julie Hayes series.

b. Anna Porter’s Judith Hayes series.

9. Mysteries in which the authors get to make use (or fun) of the famous armaments company, Smith and Wesson:

a. In Michael Bowen’s cleverly titled recent book, Washington Deceased, he has a prison guard named Wesson Smith.

b. Phoebe Atwood Taylor had a murder suspect in Spring Harrowing (1939) named Susan Remington who owns a pair of bobcats named Smith and Wesson.

c. The series characters in Annette Meyers’s Wall Street mysteries are Xenia Smith and Leslie Wetzon.

— Reprinted from The MYSTERY FANcier,

Vol. 13, No. 2, Spring 1991 (very slightly revised).

Editorial Comment: This list was put together 24 years ago. If you can add examples to any of Marv’s nine categories, please do so in the comments. And if you can add a category 10 (or more), that would be most welcome as well!

Wed 25 Jun 2014

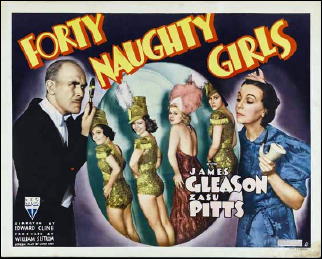

FORTY NAUGHTY GIRLS. RKO Radio Pictures, 1937. James Gleason, Zasu Pitts, Marjorie Lord, George Shelley, Joan Woodbury, Frank M. Thomas, Tom Kennedy, Edward Marr. Based on the story “The Riddle of the Forty Naughty Girls” by Stuart Palmer in Mystery, July 1934. Director: Edward F. Cline.

I know some of you may like Tom Kennedy’s lowbrow comedy performances, especially as dumb cops in movies like this and the Torchy Blaine serie, among dozens of others, if not more, and so do I, in small doses. But in Forty Naughty Girls, reportedly a Hildegarde Withers and Inspector Piper detective mystery, he should get third billing, he has so many lines, rather than way down the list of credits where you will actually find him.

The murder of a press agent for a Broadway musical who’s a man with too many ladies takes place during one of the performances of said play, with the solution coming just as the play is over for the evening. No thanks to Inspector Piper’s deductive techniques, however. His approach is to accuse someone of the crime only to discover (Miss Withers does a lot of whispering in his ear) that he’s way off base and his case just doesn’t hold up.

Miss Withers, on the other hand, does a lot of sniffing around on her own — literally, as she is on the scent of a perfume she smells on the dead man’s clothing. She also finds herself in the prop room under the stage, to much would-be hilarity, but not from me, and of course, with Tom Kennedy’s character around to pull the wrong lever, she finds herself on stage during a dance number, much to her surprise, but lose her aplomb, does she? In a word, no.

This is the last movie of six adventures of Miss Withers recorded on film, and the second of two with Miss Pitts, she of the fluttering hands and the quavering voice. She was also in the preceding one, The Plot Thickens, reviewed here. Compared to this one, the preceding one was not bad. This one? Abysmal.

Wed 25 Jun 2014

Reviewed by DAVID VINEYARD:

ANTHONY HOROWITZ – Scorpia Rising: The Final Mission. Philomel, hardcover, 2011. Puffin, softcover, March 2012.

“Somehow you are going to persuade MI6 to send Alex Rider on a mission. You’re going to make sure the mission goes wrong and the boy gets killed … Then you’re going to blackmail them.â€

That sums up the plot of Scorpia Rising, the ninth and final book (a prequel of sorts was published earlier this year) in Anthony Horowitz’s series about fourteen year old reluctant British agent Alex Rider, who finds when his secret agent uncle dies in the first book, Stormbreaker, that he has been trained all his life a be a spy, and indeed his father was an agent as well.

Stormbreaker was a clever entertaining semi send up of the genre much in the Ian Fleming tradition of tongue definitely in cheek, what with Alex’s souped up bike and a lethal yoyo and chewing gum, but what Horowitz also took from Fleming was the knowledge that you must always play it straight, and the hero is everything. The series works because of Alex Rider, because ridiculous as the idea sounds, Horowitz makes it work. This is no Cody Banks. Alex is not only a character you cheer for, but he is one you learn to understand a bit more each book.

The books grew darker as Alex was drawn deeper into the world of spies and secret agents. All nine books take place in a single crowded year, but it becomes at least plausible as long as the novels compel you along with relentless action and one twist after another, revealing the secrets behind Alex Rider.

Alex lives with Jack Starbright, a young American woman hired as a sort of babysitter, who ends up as his guardian. Other regulars include Mr. Blunt, the cold blooded head of MI6 Special Operations; Mrs. Jones, who has a jaundiced eye to the exploitation of Alex; Smithers, the head of Covert Weapons, Q to Alex’s 007; and Sabina Pleasure (Fleming would love it), a classmate involved in his first adventure and Alex’s girlfriend.

In Scorpia Rising Alex is drawn into a trap, and faces an old enemy, Julius Grief, a clone given plastic surgery to be Alex’s twin and dark doppelganger being used by Scorpia, SPECTRE to Alex’s Bond, a ruthless terrorist organization that has been at the heart of Alex problems from the beginning.

“I will not agree to take on this child one more time. Twice was enough. I will not risk a third humiliation.â€

But of course they do. There wouldn’t be a book if they didn’t. I suppose that must be very limiting for master criminals and super villains. You can imagine Moriarty complaining that once in a while it couldn’t be Martin Hewitt or Dr. Thorndyke instead of Holmes.

Scorpia Rising is the longest of the books to that point, and a fine climax for a series that turned out to be a dark look at the excesses of intelligence, and far more accessible than any of John Le Carre’s adult novels. Horowitz (of Poirot, Foyle’s War fame, and author of numerous other young adult novels — notably here the Diamond Brothers and their best known case, The Falcon’s Malteser) is clever, inventive, playful as his model Fleming was, but unlike Fleming there is a more serious theme underlying the Alex Rider books (more serious than Fleming’s ennui anyway), and the effects of his ordeal show on what is, after all, a fourteen year old. That he keeps Alex a believable fourteen year old and not an angst-ridden mini-adult is no mean feat.

There is a stunner at the end of this one, and Alex graduates to what he has been on the way to becoming all along. At the end he escapes Scorpia and Mr. Blunt, but at a price he was not willing to pay. Despite the upbeat ending, Horowitz never suggests Alex is going to simply forget what he has seen and done, or that the can go back and be a normal teenage boy now, not entirely. Everything is nicely sewed up and closed, but you won’t buy it for a moment. Alex’s new happy life in San Francisco with Sabina’s family is presented as the finale to his adventures, but you know heroes like Alex Rider stumble on massive criminal conspiracies the way the rest of us find pennies on the ground.

You leave the series fairly certain that Alex’s days with MI6 Special Operations are only suspended until he is older.

If you like spy thrillers or James Bond, this series will be hugely entertaining. The villains are properly larger than life, the action beautifully choreographed, and the set pieces big and well drawn. Above all, without ever imitating Fleming, Horowitz manages to mine what was properly called the Fleming Effect, that ineffable voice no one has been able to echo since. Like Fleming, the writing is deceptively simple, full of short sentences and with a page-turning rhythm that easily explains why young audiences devoured these.

Alex Rider inspired graphic novels, audiobooks, and a somewhat disappointing movie, Stormbreaker, that was none the less perfectly cast. If you haven’t read these, find a young adult you can buy them for, and then read them yourself before giving them to him or her. Though you may have to buy a second set because you are reluctant to let them go. They really are intelligent and playful novels with a dark and serious message hidden among the lightning action.

The Alex Rider series —

1. Stormbreaker (2000)

2. Point Blanc (2001)

3. Skeleton Key (2002)

4. Eagle Strike (2003)

5. Scorpia (2004)

6. Ark Angel (2005)

7. Snakehead (2007)

8. Crocodile Tears (2009)

9. Scorpia Rising (2011)

10. Russian Roulette (2013)

Tue 24 Jun 2014

Posted by Steve under

Authors[6] Comments

A SHORT NOTE ON AGATHA CHRISTIE’S PROFESSIONALISM

by Josef Hoffmann

The sociologist Pierre Bourdieu claimed that a literary field began to form in 19th century society that followed specific rules. These rules had to be obeyed by a writer if he wanted his literary products to be successful. Indeed, he almost had to internalise them.

For example, an author of fiction must not directly express his political or philosophical views, as an author of factual books might, but must instead translate them into the narrative of a novel, integrated into the plot or the dialogues of the protagonists, in order to comply with the rules of novel-writing. Yet the rules of the literary field are not rigid, but are adaptable to some degree, thus allowing scope for experimentation.

It is my theory that, at the time when Agatha Christie began to write her detective novels, a relatively independent literary field began to develop – the genre of the detective story – with its own specific rules. This was expressed in the discourse of the time on the rules of fair play between author and reader and the foundation of the Detection Club, which obliged its members to comply with certain rules.

Agatha Christie was so successful because she mastered the rules of the genre (which were not as narrowly defined as those of the Detection Club), rules that became second nature to her.

This becomes clear, for example, in her Miss Marple novel, The Murder at the Vicarage (1930). Almost at the beginning of the detective novel, Christie writes that the life of the parish seems to have been created for the amusement of the vicar’s young wife, and that her regular afternoon teas served the purpose of exchanging gossip. Towards the end of the novel, the vicar gives a sermon which, rather than being shaped by the Christian spirit, foams with dramatic rhetoric in order to impress the congregation.

Despite this interweaving of criticism of the church, it would never have occurred to Christie to call her novel something like “The Church Is Dead.†Instead she chose a suitable title for a detective novel, The Murder at the Vicarage, which itself is actually outrageous, as the vicarage, the centre of the Christian parish, should be a place of devotion and the love of one’s fellow man, and not the scene of a murder.

But this is accepted by the reader, whereas a title explicitly critical of the church would have met with rejection. In Hercule Poirot’s Christmas (1938), there is a murder during this festive season, despite the fact that, in the opinion of one protagonist, Christmas should be a celebration of peace and reconciliation.

But Hercule Poirot calls Christmas a time of hypocrisy. Yet the title of the detective novel is not “A Celebration of Hypocrisy,†which would certainly have damaged the sales of the book.

In his history of crime literature, Julian Symons finds fault with the fact that the General Strike of 1926 never took place in British detective stories of the Golden Age. But that is not quite right. Christie included the element of the General Strike in the narrative structure of the novel The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, from 1926. By making the narrator and assistant to the detective a murderer, she suspended the rules of fair play, quite in the manner of a general strike.

The scope of Agatha Christie’s knowledge was broader than some literary critics would like to believe.

Further Reading:

Pierre Bourdieu: The Rules of Art: Genesis and Structure of the Literary Field, Polity Press 1996

John Curran: Agatha Christie’s Secret Notebooks, Harper 2011

Curtis Evans: Was Corinne’s Murder Clued?: The Detection Club and Fair Play, 1930-1953, CADS Supplement Number 14

Howard Haycraft (ed.): The Art of the Mystery Story, Carroll & Graf 1992 (Part 2: The Rules of the Game)

Julian Symons: Bloody Murder: From the Detective Story to the Crime Novel: a History, Papermac 1992.

— Translated by Carolyn Kelly

Next Page »