June 2011

Monthly Archive

Wed 29 Jun 2011

FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

If you own a copy of the Library of America’s Dashiell Hammett volume Crime Stories & Other Writings (2001) and also a copy of Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine for July 1945, then, whether you know it or not, you have two different versions of Hammett’s Continental Op story “The Tenth Clew†(Black Mask, January 1, 1924).

The first difference between the two leaps out: the last word of the title is spelled “Clew†in both Black Mask and the Library of America collection but Fred Dannay changed it to the more common “Clue†when he reprinted the tale in EQMM.

To appreciate the final difference between the two requires a little knowledge about the story’s plot. Leopold Gantvoort, a 57-year-old widower whose net worth is around $1,500,000, is planning to marry a much younger woman, but he’s murdered before the marriage takes place and also before he’s signed a new will leaving half his fortune to her.

The Op exposes her as a confidence woman and the murderer as her scam partner, who’s been posing as her brother. Here are the last few sentences as Hammett wrote them.

[W]ith her assistance it was no trick at all to gather up the rest of the evidence we needed to hang him. And I don’t believe her enjoyment of her three-quarters of a million dollars is spoiled a bit by any qualms over what she did to Madden. She’s a very respectable woman now, and glad to be free of the con man.

What’s wrong here? Since Gantvoort was killed before either changing his will or marrying the woman, there’s no way on earth she could have inherited half his estate! Fred Dannay obviously caught this flub, and spared Hammett some potential embarrassment by taking it upon himself to rewrite those lines.

With her assistance it was no trick at all to gather up the rest of the evidence we needed to hang the man who left too many clues.

Very shortly after this story appeared in EQMM, Fred included it in the digest-sized paperback original collection The Return of the Continental Op (Jonathan Press pb #J 17), which was published in the first week of July 1945, a month or two before Hammett came back to the U.S. from Army service in the Aleutian Islands during World War II.

If any reader of this column has a copy of that edition, which I don’t, I’d love to know whether the text of this story is Hammett’s original or Fred’s revision. (My hunch is the latter.)

Settled back into civilian life, Hammett started teaching an evening course on mystery writing at the Jefferson School of Social Science, a Communist-affiliated institution on New York’s Sixth Avenue, and Fred joined him regularly as unofficial co-instructor.

When Return was reprinted in ordinary paperback format (Dell pb #154, 1947), the last paragraph of the story was unaccountably back in its original form. Had Hammett objected to Fred’s bold attempt to spare him a few blushes?

Erle Stanley Gardner’s pulp stories of the early 1930s, and his early novels as well, were hugely influenced by Hammett although in later years he resented having the fact pointed out.

In Chapter 20 of one of those early novels, the non-series whodunit This Is Murder (1935, as by Charles J. Kenny), a suspect has just been exposed as an ex-con. “Where was your first conviction?†he’s asked. “In Wisconsin.†“You served a term there?†“Yes, sir, at Waupum.â€

In fact the name of the town is Waupun, which locals unaccountably pronounce Wau-PAN. According to Wikipedia the place was supposed to have been named Waubun, which is a Native American word meaning dawn of day, but some state bureaucrat misspelled it and the mistake has never been corrected.

The town’s chief industry is prisons — three of them! — but it’s also known for having more outdoor sculpture per capita than any other city in North America. The most famous such piece in Waupun is the “End of the Trail†sculpture: a young warrior on his horse contemplates the end of life as his people had known it.

I saw it when I passed through the town years ago. The Library Bar on Waupun’s Main Street served the finest fries I’ve ever eaten. My buddy Joe Google tells me it’s no longer there. Drat!

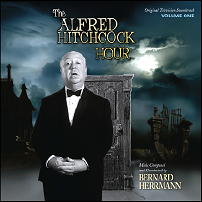

I am finishing this column on June 27, two days short of what would have been the 100th birthday of my favorite American composer. The centenary of Bernard Herrmann (1911-1975), who’s best known for having scored films like Citizen Kane, Vertigo and Psycho, is being celebrated throughout the music world, and Varese Sarabande Records has just made a huge contribution to the festivities by releasing The Alfred Hitchcock Hour, Volume One.

Herrmann wrote original scores for 17 Hitchcock Hour episodes during the program’s second and third seasons (1962-64), and this handsome two-CD set contains eight of them, more than two and a half hours of primo Herrmann never before available in audio form. Volume Two, let’s hope, will bring together the other nine — and soon. As I wrote in an earlier column, no one does ominous like Herrmann does ominous.

Tue 28 Jun 2011

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[28] Comments

Curse, Smersh!

Dashiell Hammett’s The Dain Curse

A Review by Curt J. Evans

DASHIELL HAMMETT – The Dain Curse. Alfred A. Knopf, hardcover, 1929. Reprinted many times since. TV movie: 1978 (with James Coburn as “Hamilton Nash”).

Not all Hammetts were created equal. Case in point: Hammett’s second novel, his famous family slaughter saga, The Dain Curse. Less viscerally organic than his first crime tale, Red Harvest (1929), it is also, in my opinion, vastly inferior both to his immediately following works, The Maltese Falcon (1930) and The Glass Key (1931), and even to his last novel, the slick (if rather facile) The Thin Man (1934).

I am hardly the first person to note flaws in The Dain Curse. A quarter-century ago, in his entry on the novel in 1001 Midnights, Bill Pronzini observed that The Dain Curse was “overlong and decidedly melodramatic.†Indeed it is!

Where in Red Harvest the gang violence culminating in massacre that Hammett chronicles seems to rise naturally out of the darkest strains of indigenous Americana, in The Dain Curse the bloodletting is tied to an impossible plot that resembles the more absurd Golden Age British detective fiction that Hammett purportedly despised.

If you were to ask me which 1929 detective novel is the more ridiculous when looked at objectively, The Dain Curse or S. S. Van Dine’s The Bishop Murder Case (though Van Dine was not British, he clearly was heavily influenced by the sort of classical detective story we associate most with British writers), I would be hard pressed to name the latter title, even though it involves an unbelievably baroque plot involving multiple slayings carried out on the basis of nursery rhymes.

At one late point in the The Dain Curse, Hammett’s detective, the Continental Op, stops to list for a friend the myriad acts of bloody mayhem that have occurred around him of late. I have to say I found this list hilarious:

“Are you sure,†Fitzstephan asked, “that you’re right in thinking there must be a connection?â€

“Yeah. Gabrielle’s father, step-mother, physician, and husband have been slaughtered in less than a handful of weeks — all the people closest to her. That’s enough to tie it all together for me. If you want more links, I can point them out to you. Upton and Ruppert were the apparent instigators of the first trouble, and got killed. Haldorn of the second, and got killed. Whidden of the third, and got killed. Mrs. Leggett killed her husband; Cotton apparently killed his wife; and Haldorn would have killed his if I hadn’t blocked him. Gabrielle, as a child, was made to kill her mother; Gabrielle’s maid was made to kill Riese, and nearly me. Leggett left behind him a statement explaining — not altogether satisfactorily — everything, and was killed. So did and was Mrs. Cotton. Call any of these pairs coincidences. Call any couple of pairs coincidences. You’ll still have enough left to point at somebody who’s got a system he likes, and sticks to it.â€

This passage makes Philo Vance’s “psychological†lectures at the end of The Greene Murder Case (1928) and The Bishop Murder Case seems overwhelmingly convincing by comparison. Unfortunately, it is reflective of the many pages in the novel given over to the Op’s inevitably tedious explanations of an extremely convoluted but ultimately not very rewarding mystery plot.

To be fair to Hammett, with The Dain Curse (as with Red Harvest) he was faced with the task of stitching together a novel from short stories. To make The Dain Curse stick together in one piece he was forced to use as glue the criminal mastermind gambit.

This device usually is not convincing in Edgar Wallace novels either, but then Edgar Wallace is not universally acclaimed today for having heroically and almost single-handedly (with some help from Raymond Chandler) introduced realism to the Golden Age mystery story.

This is not to say that there are not interesting points to The Dain Curse. There are times when one pleasingly can hear the wisecracking voice of Philip Marlowe and that smart ass legion of private eyes who jauntily followed Hammett’s Continental Op and Sam Spade down those mean streets:

While I waited [explains the Op when he is at the home of the well-off Leggetts], I looked around the room, deciding that the dull orange rug under my feet was probably both genuinely oriental and genuinely ancient, that the walnut furniture hadn’t been ground out by machinery, and that the Japanese pictures on the wall hadn’t been selected by a prude.

“For God’s sake let’s get her out of here — out of this house — now, while there’s time!â€

I said she’d look swell running through the streets barefooted and with nothing on but a bloodstained nightie.

And then there is simply the thrill in The Dain Curse of Hammett’s sharp and direct depictions of drug dependency and pure, elemental brute violence (which in 1929 must have been really thrilling — or appalling, depending on the reader):

“Where’s Gaby?†he gasped.

“God damn you,†I said and hit him in the face with the gun.

Although I think that, in contravention of academics who have given much serious study to it, Hammett’s treatment in The Dain Curse of a religious cult is more pulp fiction than deep thinkin’, nevertheless I was greatly amused by this sardonic observation from the Op:

They brought their cult to California because everybody does, and picked San Francisco because it held less competition than Los Angeles.

Too bad Hammett (and the Op) missed the Swinging Sixties!

Overall, however, I would say that The Dain Curse is neither a great crime novel nor even a very good one, really — though it undeniably has importance both in the study of Hammett’s development as a writer and in the development of American detective fiction.

But when it comes to melodramatically and improbably cursed genteel families and wildly overcomplicated murder plots, give me S. S. Van Dine any day of the week. Indubitably, his Philo Vance is the go-to guy when one is faced with that sort of the case.

Tue 28 Jun 2011

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[4] Comments

REVIEWED BY GEOFF BRADLEY:

DANIEL STASHOWER – The Adventure of the Ectoplasmic Man. William Morrow, hardcover, 1985. Penguin, paperback, 1986. Titan Books, trade paperback, 2009.

I’m a sucker for Sherlock Holmes stories written by hands other than Conan Doyle not because I think they’re good, but because I’m always hoping they will be. I had read some good things about this book so with fingers crossed I decided to try it.

Watson, on the death of Houdini, sends Houdini’s widow a manuscript detailing the adventure where Holmes untangled, in 1910, a plot to discredit Houdini, who was performing in London, and blame him for murder and crimes against the state.

The book could be described, I suppose, as a romp rather than an accurate pastiche. Holmes is larger that life, naturally, but his techniques seem a little far-fetched and it was surprising that he knew how to fly a plane. Still it was a light and fast read, and I have to say I quite enjoyed it, without, for a moment, taking it seriously.

Bibliographic Notes: (1) Ectoplasmic Man was nominated for an Edgar (Best First Novel) by the MWA in 1986.

(2) Several years after this book appeared, Daniel Stashower wrote a series of three novels in which Harry Houdini himself was the primary detective:

The Harry Houdini series —

1. The Dime Museum Murders (1999)

2. The Floating Lady Murder (2000)

3. The Houdini Specter (2002)

Mon 27 Jun 2011

PRIME TIME SUSPECTS

by TISE VAHIMAGI

Part 4.0: Themes and Strands (1950s Police Dramas)

The American TV police procedural and the British TV senior police detective drama of the 1950s were never the high watermark of the small-screen genre, but their influence on the formats and styles of following crime series lasted for decades.

For instance, the roots of Stephen Bochco’s highly-influential Hill Street Blues (NBC, 1981-87) or the James Arness seen-it-all-before cop series McClain’s Law (NBC, 1981-82) may be traced back to Jack Webb’s 1950s Dragnet.

Likewise, the British police dramas of the 1970s — such as New Scotland Yard (ITV, 1972-74), The Sweeney (ITV, 1975-76; 1978), even the North of England-located Strangers (ITV, 1978-82) — may trace their heritage back to the TV Scotland Yard detective stories of some twenty years earlier.

The following, therefore, is simply an overview of two significant phases in the history of the TV Crime & Mystery genre.

The Story You Are About To See (USA: 1950 to 1959). In 1950, Senator Estes Kefauver established a Senate committee to Investigate Crime in Interstate Commerce. It became known as the Kefauver Committee. Its New York hearings were televised to an enormous audience, who witnessed a parade of the most notorious American gangsters treat the Committee with utter disdain.

The TV viewers, naturally, were hungry for more, and TV fed them with Treasury Men in Action (ABC, 1950; 1954-55; NBC, 1951-54), a dramatization of true cases about counterfeiters and gangsters in U.S. Treasury files, and actual cases from police files in Racket Squad (CBS, 1951-53), with Reed Hadley starring and sometimes narrating in the role of a police captain.

In 1951 came Crime Syndicated from CBS (1951-53) offering dramatizations of actual cases from the Kefauver hearings. Rudolph Halley, former chief counsel for the Senate crime investigations, fronted the series. December 1951 saw the advent of Dragnet (NBC, 1951-59; 1967-70). The TV child of actor Jack Webb, who produced, directed and starred in the series, Dragnet soon became not only the most popular show on US television during the 1950s but changed the face of the TV genre forever.

Perhaps the first ever police procedural on TV, Dragnet was a highly stylized but thoroughly enjoyable collection of statistics (time, location, weather), police jargon, and the general drudgery of everyday police work. The stories were borrowed from the files of the LAPD. The relentless questioning of witnesses overshadowed any rare instances of gunplay. The episodes concluded with an update of the criminal’s fate.

In short, Dragnet was one of the most remarkable programs of its era. Webb and his Mark VII Productions went on to produce some of TV’s most successful procedural series (Adam-12, O’Hara U.S. Treasury, Emergency!).

Law enforcement procedurals (‘based on the files of…’) soon gathered momentum, then flooded the small-screen (until the ‘adult’ Western genre arrived). Police anthology Gangbusters (NBC, 1952) was followed hotly by Police Story (CBS, 1952), City Detective (syndicated 1953-55) and The Man Behind the Badge (CBS, 1953-54).

Legal procedurals also came into play, with Public Defender (CBS, 1954-55) and Justice (NBC, 1954-56), the latter from stories based on the files of the Legal Aid Society.

One of the more notable police procedurals of the period was The Lineup (CBS, 1954-60). The drama starred Warner Anderson and Tom Tully as a detective partnership and was produced in cooperation with the San Francisco P.D. The Lineup was CBS’ answer to the highly successful Dragnet on NBC. Nevertheless, as a taut, well-written, filmed series, it stood its ground firmly (in its semi-documentary fashion).

Multiple other ‘based on the files of..’ series filled out the decade, among them (their titles being self-explanatory): The Mail Story (ABC, 1954), Paris Precinct (ABC, 1955), Highway Patrol (syndicated 1955-59), State Trooper (syndicated 1956-59), The Tracer (syndicated 1957-58), based on the files of Tracer Co. of America (N.Y.), Official Detective (syndicated 1957-58), from stories in the title magazine, Harbor Command (syndicated 1957-58), a sort of Dragnet in a nautical setting, and U.S. Border Patrol (syndicated 1959).

Scotland Yard’s War on Crime (UK: 1954 to 1965). The British view of the Law and its various mechanisms, especially concerning Scotland Yard, was seen at first through a series of BBC documentaries and drama-documentaries (TV reconstructions) that extolled the virtues of the British police and legal services.

For instance, Murder Rap (1947), from Scotland Yard casebooks, Armed Robbery (1947), based on real-life Scotland Yard cases, It’s Your Money They’re After (1948), concerning post-war black marketeers, and War on Crime (1950), a series virtually celebrating ‘from the files of…’ Scotland Yard.

At this time, it dawned on BBC Television that the perceived glamour of ‘Scotland Yard’ was an exportable commodity.

The Oct-Nov 1951 drama-documentary series I Made News, a dramatization of a criminal who had made the UK news that week, was the first to introduce the real-life character of Detective Superintendent Robert Fabian, head of Scotland Yard’s famed Flying Squad (the Cockney rhyming slang was ‘The Sweeney,’ as in Sweeney Todd).

The drama series Fabian of the Yard (BBC, 1954-57), filmed by Trinity Productions/Antony Beauchamp Productions for BBC, became as popular and as influential to the British TV genre as Jack Webb’s Dragnet (NBC, 1951-59) had been, in its way, to the 1950s American TV genre.

In truth, there was absolutely nothing astounding about the plots, save for their being based on real-life cases. But it was while emphasising the exploits of Detective Superintendent Fabian (during an era when people were defined by the superiority of their work) and the activities of Scotland Yard, it can be summed-up fairly as a good police procedural (for the mid-1950s) with actor-star Bruce Seton’s calm, perceptive doggedness leading the painstaking investigation work. In retrospect, perhaps more a measured film noir than a high-octane police thriller.

No sooner had it aired when the BBC received a complaint from Scotland Yard accusing the series’ producers of misrepresenting Metropolitan Police procedure as well as over dramatizing some events (apparently, it was the sadistic method used by the wife-murderer in the “Brides of the Fire” episode).

However, Fabian of the Yard made a big impact on 1950s British TV viewers, with series’ star Seton and the real-life Bob Fabian elevated to a god-like status. The series also scored financially via showings on NBC in 1955 (sometimes as Inspector Fabian of Scotland Yard) and as the syndicated Patrol Car. Two feature films (of re-edited episodes) were released to cinemas as Fabian of the Yard (in 1954) and Handcuffs, London (1955). The real Robert Fabian of the Yard died in June 1978 at the age of 77.

Other UK series attached to the theme of Scotland Yard, by title or through deed, included the atmospheric whodunit dramas of Colonel March of Scotland Yard (shown via ITV, 1955-56; syndicated in the US; produced circa 1952 and 1954). It was loosely based on the 1940 story collection The Department of Queer Complaints by John Dickson Carr (writing as Carter Dickson). The series featured an eye-patched Boris Karloff, a detective who concentrates on bizarre crimes.

Robert Beatty was a Canadian Mountie (a Detective Inspector) attached to Scotland Yard in Dial 999 (ITV, 1958-59) and solved various London-located crimes. (999, incidentally, is the UK police emergency number, similar to 911.) Man from Interpol (ITV, 1960-61) featured a special agent (played by Richard Wyler) from the Scotland Yard branch of Interpol. In 1961, a Scotland Yard operative, Det-Insp. Bollinger (Louis Hayward), and his police dog appeared as The Pursuers (ITV). Unfortunately, all were standard small-screen cops-and-robbers dramas.

Stryker of the Yard, with Clifford Evans (as Chief Inspector Robert Stryker), was a peculiar one. Apparently, it first appeared as a series of B-movies in British cinemas during the early 1950s. Then, they were re-edited and shown on NBC in 1957. As a TV series, it also showed up as half-hour episodes on UK’s Associated Television (ATV) from November 1961 to January 1962. A compilation film, Stryker of the Yard, was released in 1953.

Perhaps the most popular (post-Fabian) Scotland Yard detective series of the 1950s (and 1960s) was No Hiding Place (ITV, 1959-67), featuring the crime-busting investigations of Chief Superintendent Lockhart (played with suitable bank manager authority by Raymond Francis). While this British ‘age of acquiescence’ continued to be ruled by the authority figures of Scotland Yard, it wasn’t too long before Lockhart replaced Fabian as the omnipotent one in the viewing nation’s hearts.

The series was oddly reminiscent of the Edgar Lustgarten Scotland Yard B-movies shown in the UK from around 1953, with detectives that looked like insurance salesmen constantly springing out of dark cars.

No Hiding Place evolved from two earlier series: The Murder Bag (ITV, 1957-59) and Crime Sheet (ITV, 1959), two police detective series also popular with 1950s UK viewers. In retrospect, however, No Hiding Place was a rather routine detective drama series, not always persuasive (though some robbery/murder scenes were quite convincing) and — apart from Francis’s dogged detective character — often uninteresting in performance. Plot-wise, coincidence was stretched almost to breaking point.

On a final but justly deserved Scotland Yard-related note, Gideon’s Way (ITV, 1964-66), based on the character and stories created by John Creasey (writing as J.J. Marric), was an uncommonly intelligent filmed drama series with John Gregson as Commander George Gideon. In many ways it may be regarded as the UK’s television equivalent to America’s excellent Naked City (hour series; ABC, 1960-63). In the former, London was the multi-shaded central character; the latter explored the unpredictable New York City.

Another significant element of the history of the TV Crime & Mystery was the Anthology series (now a long-forgotten small-screen form); its sometimes brilliant crime and mystery plays and its fine coterie of writers (teleplay or novel). Part 5 intends to look at this Theatre of Crime (ranging from Suspense to Kraft Mystery Theatre to The Short Stories of Conan Doyle).

Note: The introduction to this series of columns by Tise Vahimagi on TV mysteries and crime shows may be found here, followed by:

Part 1: Basic Characteristics (A Swift Overview)

Part 2.0: Evolution of the TV Genre (UK)

Part 2.1: Evolution of the TV Genre (US)

Part 3.0: Cold War Adventurers (The First Spy Cycle)

Part 3.1: Adventurers (Sleuths Without Portfolio).

Mon 27 Jun 2011

FLY-BY-NIGHT. Paramount Pictures, 1942. Richard Carlson, Nancy Kelly, Albert Bassermann, Miles Mander, Edward Gargan, Adrian Morris, Martin Kosleck, Walter Kingsford, Cy Kendall, Nestor Paiva, Marion Martin, Oscar O’Shea, Mary Gordon, Clem Bevans. Based on a story co-written by Sidney Sheldon. Director: Robert Siodmak.

It was a cold and stormy night. The lightning crashes, the thunder rolls, and the rain is coming down in torrents. The gates of the Riverford Sanitarium are locked up tight. Nonetheless one of the inmates, locked up behind steel bars, kills a guard and makes his way over the wall.

Eluding the guards on his trail, he finds his way into Dr. Burton’s car — temporarily out of gas and marooned — and at gunpoint forces the young physician to aid and abet his getaway. He’s no maniac, he tells the doctor. He works for a famous chemist who’s invented a substance called G-32 that a gang of spies are determined to get their hands on.

Leaving the hotel room where they’ve holed up at for a short moment, Burton (an equally young and very earnest Richard Carlson) returns to find the man dead, murdered by one of his own scalpels. Do the police believe a word of this? Not for a minute.

Now on the run himself, Burton commandeers the aid of a young and beautiful brunette (redhead?) staying in a room below, a sketch artist named Pat Lindsey (Nancy Kelly, to those of us who’ve read the credits). And they’re off and running, in one of the most amusing screwball mysteries I’ve had the occasion to watch in a long long while.

Not laugh-out-loud funny, but amusing in the sense of a smile to yourself when another “I can’t quite believe this†scene comes along. Besides their finding a secure hideaway with a rustic justice of the peace and his family, who have their own ideas as to why they’re on the run, there’s some absolutely top notch stunt work involved, as the pair jump from the lady’s automobile they’re driving, up onto a car carrier filled with new cars, hopping into one of them, then releasing it backwards onto the highway, all while going full speed away from both the police and the gang that’s not far them.

Whew! This movie was not at all what I expected from the opening scene, which I described in a lot more detail than I will the couples’ further quarreling adventures, which I will leave to you find and discover on your own, and delightfully so, if you do.

Of the cast, most of them were only names to me. Richard Carlson, of course, and Nancy Kelly (sister of Jack Kelly) who later on won a Tony and was nominated for an Oscar, but the others, while they were all terrific in their parts, they don’t win awards for movies like this one. (But maybe they should.)

Sun 26 Jun 2011

REVIEWED BY BARRY GARDNER:

NINA KIRIKI HOFFMAN – The Thread That Binds the Bones. Avon, paperback original, 1993.

I don’t find much fantasy that I like anymore, whether it’s a function of my own jaded sense of wonder or they’re just not writing ’em like they used to. I enjoyed this one.

It’s the story of a strangely talented young man who blunders into an even more strangely talented family living in the Oregon boondocks, and what happens between them. Reminds me a bit of Suzette Haden Elgin’s Ozark novels, though it isn’t as good. The plot has holes in it, but the writing’s good, and the characters are engaging.

— Reprinted from Ah, Sweet Mysteries #7, May 1993.

Editorial Comment: I haven’t finished looking through all of Barry’s old reviews, but this is the first I’ve come across that’s either a fantasy or science fiction novel. By my usual standards it’s too short to post, but I thought in this case I’d make an exception.

Sun 26 Jun 2011

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[4] Comments

REVIEWED BY WALTER ALBERT:

JOHN GRISHAM – The Pelican Brief. Bantam, paperback, 1993; Doubleday, hardcover, 1992. Film: 1993, with Julia Roberts & Denzel Washington.

A friend showed up on my doorstep and pressed this into my hands, saying only that this was a page-turning read.

Well, it was, if you count skipping about 3/4 of the book as you race forward to the denouement as page-“turning.” I can’t believe that Grisham is as popular as he seems to be currently. The book is long, turgid and sloppily written. Don’t they have literate copy-editors anymore at any of the publishing houses?

I didn’t stop to document any of the linguistic atrocities, but several of them brought me up short. Spare me any more Grisham. Life is too short and time too precious to waste on this pre-digested pablum.

— Reprinted from

Walter’s Place #95, May 1993.

Sun 26 Jun 2011

Posted by Steve under

ReviewsNo Comments

HUGH PENTECOST – Random Killer. Dodd Mead, hardcover, 1979. Hardcover reprint: Detective Book Club, 3-in-1 edition, October 1979. Paperback: Dell, Scene of the Crime Mystery #24, 1981.

Although fictional, the Hotel Beaumont, located in New York City, is the model that all the world’s other fine luxury hotels must pattern themselves after. It is indeed a small city within itself, and Pierre Chambrun’s staff keeps everything working like clockwork.

Until, that is, the week a crazed killer’s series of strangulation murders has the patrons packing up and leaving for elsewhere in panic. A pattern does at last emerge, one that connects the several deaths to that of a ski instructor in Colorado two years earlier.

In spite of the enormity of the coincidence required to bring all the right people together at the same time in the same hotel — Chambrun’s — Pentecost’s flair for adapting headline-making drama keeps the story alive and continually in motion.

Rating: B minus.

— Reprinted from

The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 3, No. 6, Nov/Dec 1979 (slightly revised). This review also appeared earlier in the

Hartford Courant.

Sun 26 Jun 2011

Posted by Steve under

ReviewsNo Comments

IT IS PURELY MY OPINION

Reviews by L. J. Roberts

MICHAEL CONNELLY – The Reversal. Little Brown, hardcover, October 2010. Premium-sized paperback: Vision, August 2011.

Genre: Legal Mystery/Police Procedural. Leading characters: Mickey Haller (3rd in series) & Harry Bosch (16th). Setting: Southern California.

First Sentence: The last time I’d eaten at the Water Grill I sat across the table from a client who had coldly and calculatedly murdered his wife and her lover, shooting both of them in the face.

Jason Jessup has spent the last 24 years in prison, convicted of kidnapping and murdering a 12-year-old girl. New DNA evidence has won him a new trial, but the LA DA’s office can not use one of their own to prosecute the case.

Instead, they hire defense attorney Mickey Haller to switch sides. Mickey agrees to prosecute the case as long as he runs the case with his ex-wife Maggie McPherson as 2nd chair and LAPD Det. Harry Bosch as

investigator.

You can never go wrong with a book written by Connelly, and this is one of his better books. From the very beginning, you are involved and want to keep reading to the last page. It really is a legal thriller.

The story is much more plot-driven than character-driven. Certainly there are details of each character’s personal life — it wouldn’t be realistic without them — but the story focuses on the case. While that did mean there was less character development than I’d have liked, it made sense with the trajectory of the story. To do otherwise, may have bogged things down.

The drama is split between the investigation and the courtroom. And drama there is. Connelly creates an excellent sense of tension without ever going over the top. When there is threat, it feels real. When there is emotion; that too is realistic.

The courtroom scenes were ones I found fascinating. From pre-trial, to dealing with the political and media pressures, jury selection, and legal maneuvers, having just served on a criminal-trial jury, it all seemed very real to me. The ending was not as satisfying as I might have wished, but it was more realistic than a more classic ending.

One element I did find disconcerting was the alternating voices. I do wish it had all been done in third person, but I understood why it was not. However, it was a bit confusing at times.

I’ve always said there is nothing wrong with a “Good” book. This was more than “Good” but still falls in that range. It is a four-hour, straight-through, airplane read, and that is not meant to be a disparaging term. It does mean it’s a book in which one becomes so engrossed, you can tune out everything else around you, go for the ride, and finally breathe at the end, looking around you to remember where you really are.

In other words; I really enjoyed reading it!

Rating: Good Plus.

Sat 25 Jun 2011

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[6] Comments

A REVIEW BY RAY O’LEARY:

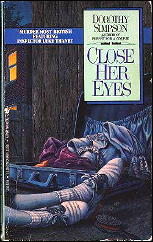

DOROTHY SIMPSON – Close Her Eyes. Bantam, paperback, 1985. Hardcover edition: Scribner’s, US, 1984. First published in the UK: Michael Joseph, hc, 1984.

Detective Inspector Luke Thanet is called in on his day off when a 15 year old girl is reported missing; Charity Pritchard and her girlfriend were supposed to be at a Youth Hostel while her parents were away, but it seems the girlfriend took ill and Charity… well, she left the girlfriend’s house just minutes before Thanet and Sgt. Lineham showed up looking for her, but an hour later she’s found dead on the shortcut to her house — and evidence turns up that she’s not the Little Innocent everyone took her for.

I sampled Simpson’s Thanet novels years ago, but got so ticked off by Puppet for a Corpse [see below] that I didn’t return to her until just recently. I found this one a pretty decent effort, though the killer was pretty evident from the get-go and I wondered what took Thanet so long to get around to him.

(Why Puppet? WARNING: SOLUTION REVEALED! See Comment #1.)

Next Page »