Fri 15 Nov 2024

Interview with Bob Pierce about William Lindsay Gresham, by G. Connor Salter

Posted by Steve under Authors , Interviews[3] Comments

about William Lindsay Gresham

by G. Connor Salter:

The writer William “Bill” Lindsay Gresham (1909-1962) is well-remembered for his 1946 novel Nightmare Alley, but not much is known about his life. He was a member of New York-based writers group the Witchdoctors Club, particularly close to Clayton Rawson and John Dickson Carr, and wrote what some consider “the first great Houdini biography.”

Two of the few people today who can speak about Gresham from memory are his stepchildren, Bob Pierce and Rosemary Simmons. Bob and Rosemary moved with their mother, Renee Rodriguez (nee Pierce), to Staatsburg, New York, in 1952 to stay with Gresham’s family. Renee was a cousin of Gresham’s wife, Joy Davidman. As various books on Davidman have discussed, Renee was seeking a divorce from her husband, Claude Pierce, and she married Gresham after he divorced Davidman in 1954. Gresham helped raise Bob and Rosemary until his death in 1962.

In our interview, Bob recalls growing up with Gresham, and some memories of spending time with Gresham’s sons, David and Douglas, in 1952-1953 before they moved away with Davidman.

Interview:

Q. How old were you when you, your mother, and Rosemary came to stay with the Greshams in Staatsburg?

A. I was 5-6 years old. I remember riding the school bus, so I must have been in first grade.

Q. What is your first memory of Bill Gresham?

A. I don’t recall any first impressions. I do remember a large house with columns and a front yard that sloped down to a creek. The kitchen was large and came with a friendly cook.

Q. Did you relate well to Bill?

A. I did not. I was my daddy’s little boy who got taken everywhere with him, even to the bar. I gradually warmed up to [Bill] and somewhere around 13, I asked my mother if I could call him Dad instead of Cousin Bill. Unfortunately, I never got around to following through.

Q. Can you recall Bill saying anything about his writing – what he was working on, projects he liked or disliked, things like that?

A. While I was aware that he was a writer and made contributions to various magazines, the only project we ever discussed was his Book of Strength. We discussed the exercises in the book. I was aware of his keen interest in Houdini, but don’t remember discussing the book. I was also aware of his interest in magic.

He also dabbled in something called I Ching (I think that is right), which was some sort of Oriental graphic with a set of horizontal lines. One day he sat down with me trying to explain that you could ask questions and I Ching would provide an answer. I tried asking a question about a girl I had a crush on. All this was spelled out on a yellow pad, which I later found out my mother found and had some questions about who this girl was that was on Bill’s pad.

Q. Any memories of his body-building exercises when he was working on The Book of Strength (1961)?

A. We did discuss his book and the illustrations he planned to use. Being rail thin, I had interest in the activities. My memory is vague, recalling that there may have been a homemade exercise bench and maybe some trips to a local gym. He taught me proper breathing techniques when exercising, which I employ to this day. He dedicated the book to his sons, David and Doug, and to me, giving me a first presentation copy that I still have.

Q. Any memories of the fire-eating and other tricks that Gresham would do?

A. I do remember him entertaining friends by eating a flaming banana. He would also juggle flaming cotton balls. He shared the secret of fire eating with me, which was to use isopropyl alcohol because it burns cool. He could also roll a quarter across his knuckles. I don’t remember any card tricks, but I suspect he knew a few.

Q. Any memories of him playing guitar or singing?

A. I do remember him doing both, but no specific memories.

Q. Any memories of what Gresham’s wife, Joy, was like?

A. I only have vague memories of her. I don’t recall her being friendly or warm and seemed to favor her oldest son, David, who was prevented from bullying my sister and I by his brother Douglas.

Q. If you can remember Joy, how did she and Gresham relate to each other—happy. Unhappy, any impressions from that period?

A. I have no recollections of their interactions.

Q. Any memories of the Gresham boys, Douglas and David?

A. As referenced above, my relationship with David was strained although I can’t cite any specifics. Douglas was seen as our protector from David and we enjoyed a positive relationship with him. An example would be the Halloween we shared. My mother made costumes for all four kids. Douglas was Robin Hood, Rosemary was Maid Marion, I was Will Scarlett, and David was the Sheriff of Nottingham. We were perfectly role-cast.

[Interviewer’s Note: Rosemary recalled in an interview for Fellowship & Fairydust that David refused to dress as the Sheriff of Nottingham and asked for a Julius Caesar costume instead. They both described David as picking a role that fit him well.]

Q. When did your parents, Claude and Renee, divorce?

A. I have always believed that I was five at the time. I remember leaving for the airport (I think) and my father ran into a ditch. (Only later did I learn he was drinking). A passerby picked us up and drove us to the airport. I remember being aware that something traumatic was occurring, but no details. I don’t know when the divorce was officially granted.

Q. How much was your father Claude involved in your life after the divorce?

A. Mostly absent. I only remember one time when we were living in the Miami area that he came to visit with his girlfriend and they took Rosemary and I to visit my grandfather in Mobile. At some point, maybe I was 10-12, Claude got a job as a pipefitter, I believe, and lived in Queens, NYC. On occasion, he would come to New Rochelle, and pick us up and take us back to Queens for the weekend. I would guess I didn’t see him more than a dozen times. It was during this time that I realized that my father was an alcoholic and asked my mother for confirmation. To my mother’s credit she never once said negative things about my father.

After he moved back to Mobile, I never saw him again. I think that had a psychological impact on me that I suppressed and shaped my adolescent personality, but he became a non-entity. There were no phone calls or letters or birthday cards that I can remember. I only found about his death several years after he passed through an aunt who eventually contacted my mother. My sister and I contributed to a headstone for him, but I don’t know where he is buried and have had no contact with my father’s side of the family.

Q. I know Gresham’s friend in Mamaroneck, Clayton Rawson, had children near your and Rosemary’s ages. Any memories of hanging out with Clayton Jr. or the other children?

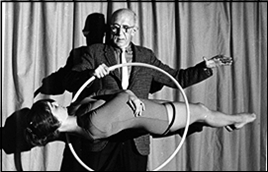

A. We never hung out with the Rawson kids. However, I do remember the family being invited over to the Rawsons one weekend. Rawson had constructed a wooden stage that rose about one foot off of his backyard. He put on a magic show for us, the highlight of which was a levitation trick in which he elevated his daughter from a standing position to a horizontal floating position with her elbow on a broomstick. He did the usual display of passing a hoop around her body to prove there were no wires. I was truly amazed because this done on a makeshift backyard stage. Bill would never tell me how the trick was done.

Q. I know that your family moved to Florida after 1953 and lived there for a few years. What was it like living there?

A. Before Bill came down to marry my mother (a ceremony I have no recollection of), we lived in a converted detached garage that had no hot water (showers consisted of a mad dash under the shower head) and we fondly called it Scorpion Hall. So named because my sister and I would capture the scorpions that ran around outside under a glass. I had no sense of being poor and economically lower-class because although we had little my mother dressed up in Easter finery: a suit for me and dress, hat and purse for Rosemary. I have the picture to attest to it.

When Bill joined us, we first moved to an apartment over a blacksmith shop and then to a duplex in Hialeah and led a normal childhood: learning to ride my first bike, performing circuses in the yard with my acrobatic sister and a blowup wading pool, hanging out and drinking Yoo-Hooo, and all the things kids in the 50s did. I was only vaguely aware of Bill’s drinking, but too young to make much of it and it didn’t spill over to disrupt the family peace.

The next stop was Ocala where we lived in a big old house on the outskirts of town. I remember going to school in some converted army trailers (I don’t know why). We then moved for some reason into town into a second-floor apartment. I have fond memories of getting up early to ride my bike to school to play in the daily pickup baseball game.

It was also here that I received my first taste of racial reality in the South, being completely naïve at the time. Rosemary and I had made friends with a pair of sisters who lived across the street that were near out age. The younger sister had some sort of disability (possibly polio) but was sweet and friendly and the older sister was not. For some reason, we disclosed that our mother was born in Havana. The next day the older sister informed us they couldn’t be our friends because everyone knows that Cubans are niggers.

The younger sister tried to stay friendly with us but we parted ways. I don’t remember being traumatized by this and race was never a topic in our household. Our stay in Ocala was short-lived as Bill thought he would secure more writing assignments if he lived closer to the literary agents in New York.

Q. What were your mother and Gresham like as a couple?

A. I think they were very loving to each other, and I can’t recall ever witnessing a fight or argument. They were affectionate in our presence and the family always ate together and watched TV together (TV dramas like Masterpiece Theater and concessions to younger tastes such as trying to outdraw Matt Dillon on Gunsmoke). I remember that when my mother noticed a few gray hairs, Bill dubbed her Princess Dark Cloud With Silver Lining.

I think I was aware that he found my mother very attractive although I was too young to understand what that meant. Proof and realization of their bond came to me after his death as my mother exhibited a belief that he was irreplaceable.

Q. Gresham served as a medic in the Spanish Civil War. Do you remember him ever mentioning Spain, anything about his war experience?

A. I have no recollection of him ever mentioning his experiences and only learned after his death that he was a participant. You state he was a medic, a fact I just learned.

Q. Any memories from when Gresham passed away in 1962?

A. My memories of that time are of people coming to the apartment to console my mother and I was assigned the task of answering the telephone and informing callers that he had passed away. I don’t recollect that I knew how he died, but I think I must have been told.

One male visitor, I don’t know who, took me aside and told me it was my role to take care of my mother and sister as the male of the house, right out of a movie. That summer I did not go to summer camp, as was my usual practice and stayed home to fulfill my expected role.

At some point I was told he was suffering from incurable cancer and took his life to spare the family the burdens of dealing with the disease. Sometime afterwards, I don’t remember how long, my mother asked me to accompany her to the pier in New Rochelle where the ferry to Fort Slocum docked and we distributed his ashes into Long Island Sound.

Q. Did you reconnect with Douglas or David as adults?

A. I never had any connection with David since my childhood. I had in-person contact with Douglas twice. Once when he was in Florida on business and he took time to visit with my mother, Rosemary, and I. Douglas arrived with his wife Merrie, all his kids, and a nanny. Douglas was dressed in boots and safari clothes. I thought I was meeting Crocodile Dundee of movie fame. The second time was when he came to visit my mother in hospice in 2005. All other contact was secondhand through my sister who maintained contact with Douglas and his family.

Several years ago, I sent a letter to Douglas thanking him for his generosity towards Renee and my sister and I. I also said that I was grateful to have a stepbrother who protected Rosemary and I from David. Douglas responded to my letter that he was glad to have a brother who wasn’t crazy.

[Interviewer’s Note: Rosemary recalls this first visit to Florida occurred in 1980. David passed away in 2014, and Douglas reported in a 2020 interview with First Things that their uncle, Howard Davidman, diagnosed David with paranoid schizophrenia when David was 11.]

Q. Have you explored any of Gresham’s writing? If so, what do you like? Or dislike for that matter?

A. I have read Nightmare Alley, which I found somewhat difficult to read. I found it to be a deep dive into a psychological world that I found unsettling and unlike any other book I have read. Of course, I read The Book of Strength which is straightforward. I attempted Limbo Tower but never got through it and I know I read numerous magazine pieces but can’t recall any of them now.

Q. Did you get to meet any of Gresham’s friends – fellow writers like John Dickson Carr, people he knew through magician groups – during or after his death?

A. John Dickson Carr is a familiar name, but I can’t remember any details about him. The most frequent visitor was The Amazing Randi. I remember him as diminutive in stature with a dark goatee and recall seeing him on TV also.

There were others, but I don’t recall them except one who invited the family, and others, to his estate, on the New Jersey shore. For some reason, I believe the host was a well-known Civil War historian. The highlight of the party was Bill and the host staging a séance that evoked some shrieks when a ghost appeared and laughter when the ghost’s identity was revealed and the prank exposed.

[Interviewer’s Note: I asked Bob in a follow-up email if this was writer Fletcher Pratt and he immediately recognized the name. Bill Mullins has noted that Gresham’s brother Henry listed Pratt as his employer on his 1940 draft card. Frederik Pohl’s blog The Way the Future Was included a story about Gresham visiting Pratt’s New Jersey home, a writing commune dubbed the Ipsy-Whipsy Institute.]

Q. Nightmare Alley has been adapted twice – into a 1947 movie and again in 2021. Have you seen either film? Any thoughts on them?

A. I have seen them both. The 1947 version had an easily followed story line of descent into alcoholic depravity fostered by hubris and guilt. The 2021 version featured a more stylized script that I thought was lacking in character development and interaction. Neither of them captured the dark psychological tone of the book.

Q. Looking back now, what’s your impression of Gresham?

A. I have learned more about Bill Gresham after his death than when he was alive. I regret not interacting with him more closely as I have come to understand that he was a very interesting and talented person from whom I could have learned much. I find no fault with him in the development our relationship, but I look back on those years as a typical adolescent too engrossed in finding himself and the social situation into which he fit.