Tue 30 Dec 2025

A Western Movie Review by Dan Stumpf: THE MYSTERIOUS RIDER (1938).

Posted by Steve under Reviews , Western movies[3] Comments

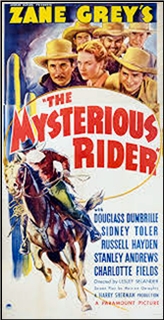

THE MYSTERIOUS RIDER. Paramount Pictures, 1938. Released to TV stations in 1950 as Mark of the Avenger. Douglass Dumbrille, Sidney Toler, Russell Hayden, Monte Blue. Based on characters created by Zane Grey. Produced by Harry Sherman. Directed by Lesley Selander.

The Mysterious Rider is yet another of those dumb-title movies that no one ever heard of and that someone seems to be writing about all the time. It has a mildly interesting mystery angle to it, and there’s a fascinating story behind its making, but if you’re looking for hard-core Mystery and have little patience with B-westerns, you might as well skip the rest of this and move on. I won’t mind a bit.

Still here? Okay, the story centers around one of the hoariest cliches of the Western, the Good Bad Guy, in this case, a notorious Road Agent who, years before, fled his ranch and family and turned to crime after killing his partner under rather dubious circumstances.

As the story picks up, he is returning Ulysses-like, to the old homestead . where he is no longer recognized, only to find his family usurped and his daughter besieged by unworthy suitors.

How he takes a job as a menial on the land he once owned and manages to restore his legacy to his kinfolk, sort out a few ornery cattle rustlers and related owlhoots, and manage to stay out of the local pokey constitutes the basis of this sincere if meager narrative.

By the time they made this, Producer and Director Sherman and Selander were already old hands a the Minimalist Western. Sherman in particular had launched the incredibly durable Hopalong Cassidy series and was in the middle of a string of oaters starring George Bancroft, who ten years earlier had starred in Von Sternberg’s Underworld and the next year could be found high on the credits of John Ford’s Stagecoach.

As I say, Bancroft was all set to star in this Mysterious Rider thing; Sherman had hired a writer with a good eraser to re-fit an old script, he’d cast the film, lined up the stuntmen, rented Gower Gulch for a few days and auditioned the horses when Bancroft struck for more money.

Well, Harry Sherman had a soft spot for has-beens (as witness his resurrection of William Boyd) but e must have decided he’d be damned if he was going to raise George Bancroft’s salary, because he told George to go ahead and walk which left him (Sherman) in the unenviable position of having to find — and damquickly — an actor who looked like George Bancroft’s stuntman.

The actor he settled on was Douglas Dumbrille, the stuffed-shirt foil for comedians from the Marx Brothers to the Bowery Boys, red herring in no less than three of the Charlie Chan films, and oily villain of countless low-budget sagebrush sagas.

Movie fans with good memories ay recall him putting bamboo shoots under Gary Cooper’s fingernails in Lives of a Bengal Lancer.

It proved to be inspired casting. Dumbrille has enough villainy in his demeanor to suggest a career of misdemeanor. Watching him, one gets the feeling that this guy might actually once have been a Road gent. And his type-cast stuffiness translates here to an oddly moving shabby dignity as he tends the kennels or wanders like a taciturn King Lear across his erstwhile kingdom.

To be sure, the script is nowhere near intelligent enough to support all this, most of the acting could be charitably described as Pedestrian (particularly Sydney “Charlie Chan” Toler as a Comical Side-kick) and the Mysterious Rider himself visibly drops about twenty pounds whenever he pulls on his mask and the stunt-man takes over, but director Lesley Selander had talent enough to capitalize on Dumbrille’s surprisingly off-beat charm and inject his own easy-going economical grace into the proceedings.

The result is distinctly one-of-a-kind and definitely worth a look.

NOTE: For more, much more from the pen (?) of Dan Stumpf, check out his own blog, filled with great fun and merriment at https://danielboydauthor.com/blog