Tue 27 Jul 2021

A Book! Movie!! Review by David Vineyard: A. MERRITT – Seven Footprints to Satan // Film (1929).

Posted by Steve under Pulp Fiction , Reviews , Science Fiction & Fantasy , SF & Fantasy films , Silent films[23] Comments

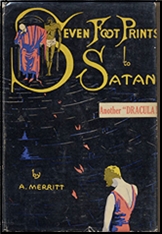

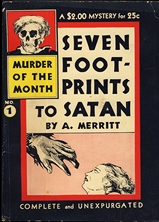

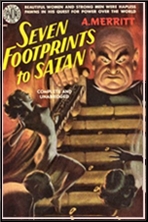

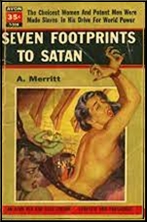

A(BRAHAM) MERRITT – Boni & Liveright, hardcover, 1928. First published as a five-part serial in Argosy Allstory Weekly between July 2 and July 30, 1927. Reprinted many times, both in hardcover and paperback, including Fantastic Novels Magazine, January 1949.

SEVEN FOOTPRINTS TO SATAN. First National, 1929. Thelma Todd, Creighton Hale, Sheldon Lewis. Screenplay by Richard Bee (Benjamin Christensen), based on the novel by Abraham Merritt. Title Cards by William Irish (Cornell Woolrich). Directed by Benjamin Christensen. First released as a silent film and later as a part-talkie.

The club is the Discoverer’s Club in New York, and the uneasy narrator is James Kirkham, adventurer and explorer, who is about to find himself in an urban nightmare out of the Arabian Nights by way of the Twilight Zone, as in short order he will be confronted by his own double and find himself in a deadly real game with a fortune at stake, his soul in peril, and Satan incarnate spinning the wheel.

Abraham Merritt is best known as a fantasist and author of scientific romances full of implausible plots, unclad other worldly women, and sensual lush prose pitting his heroes (Merritt heroes always seemed to be falling through mirrors or the equivalent into sensual violent dreams) against strange half worlds and ungodly creations. His best known titles like The Ship of Ishtar, Face in the Abyss, The Moon Pool, and The Metal Monster were highly influential on writers such as Lovecraft, Howard, and Clark Ashton Smith as well as the likes of Fritz Leiber, Henry Kuttner, C. L. Moore, Leigh Brackett, Ray Bradbury, and many more. Merritt also wrote two famous horror novels where crime and the fantastic mixed in Creep Shadow and Burn Witch Burn (which features a cross dressing vengeance obsessed madman who turns living people into murderous dolls and was made into an MGM film with Lionel Barrymore).

I won’t kid you that the plot here is ever plausible, but then neither does Merritt. His saving grace as a writer, beyond his graceful style and vivid imagination, was that he plunged headlong into the swirling madness that confronted his heroes and dragged the reader right with them. Merritt, like Dunsany before him, had a true gift at spinning fancies, terrors, and dreamscapes that were by turns gilded fantasy and soul numbing horrors.

This one is a Gothic nightmare out of the true tradition of Shelley, Lewis, and Mrs. Radcliffe but with a modern pulp sensibility.

In the dark Kirkham encounters a stranger (“I saw a dark, ascetic face, smooth-shaven, the mouth and eyes kindly and the latter a bit weary, as though from study.”) who engages him in a strange conversation:

I looked at him more closely. It was an odd remark, considering that I had unquestionably started out that night for adventure…

“That ferryboat yonder,” he pointed, seemingly unaware of my scrutiny. “It is an argosy of potential adventure. Within it are mute Alexanders, inglorious Caesars and Napoleons, incomplete Jasons each almost able to retrieve some Golden Fleece–yes, and incomplete Helens and Cleopatras, all lacking only one thing to round them out and send them forth to conquer.”

“Lucky for the world they’re incomplete, then,” I laughed. “How long would it be before all these Napoleons and Caesars and Cleopatras and all the rest of them were at each other’s throats — and the whole world on fire?”

“Never,” he said, very seriously. “Never, that is, if they were under the control of a will and an intellect greater than the sum total of all their wills and intellects. A mind greater than all of them to plan for all of them, a will more powerful than all their wills to force them to carry out those plans exactly as the greater mind had conceived them.”

“The result, sir,” I objected, “would seem to me to be not the super-pirates, super-thieves and super-courtesans you have cited, but super-slaves.”

The curious man is Dr. Consardine and in very short order, he and a beautiful girl who calls herself Eve Walton claim Kirkham is the girl’s mentally unstable sweetheart and virtually kidnap him under the eyes of the police (The game was rigged up against me all the way…), delivering him to a mysterious destination somewhere in Westchester or Long Island (“I saw an immense building that was like some chateau transplanted from the Loire. Lights gleamed brilliantly here and there in wings and turrets.”) where he meets his mysterious host, who knows far more about Kirkham than he should and who finally introduces himself with a strange offer.

“And what I offer you is a chance to rule this world with me — at a price, of course!”

It turns out Eve Walton and others in the employee of Satan are unwilling pawns in his game, an elaborate and hellish game where each individual must wager his life and free will against a promise of fabulous wealth. There are seven shining footprints of Buddha, three are holy, three doom whoever steps on them. Satan has set up an unholy game in an elaborate temple in which the players risk their souls to attain the three holy footsteps that lead to Nirvana on Earth, wealth, wisdom, love, happiness, health … all things men and women will risk their lives for.

Kirkham, ever the gambler, has nothing to lose, but he is playing the game for higher stakes than even Satan imagines. As is usually true with Merritt, the conclusion is no disappointment with retribution, madness, drugged slaves, gunfire, explosions, and madness let lose when Satan overplays his hand.

Seven Footprints to Satan came to the big screen in 1929 under the capable hand of director Benjamin Christensen and with title cards by a young Cornell Woolrich using his William Irish by-line. A well known cast including Thelma Todd and Creighton Hale starred, and the result might have been fascinating because Woolrich certainly knew something about wringing the last ounce of suspense out of purple prose and outlandish nightmare plots — but alas Christensen and the studio decided to make a comedy out of the book in the style of The Cat and the Canary, and the result is a mildly diverting mess that turns out to be a variation on Earl Derr Biggers’ Seven Keys to Baldpate. Without giving that plot away I will only say it is the most annoying in the genre.

But we have the book, a fine mix of melodrama and terror replete with a satisfying bloody-mindedness where needed, a splendid larger than life villain, clever hero, and enough sheer gall and narrative drive to compel the reader through the unlikely goings on. It is far from Merritt’s best work, but it has its own loony internal logic if you give yourself over to it, and its author writes rings around most of the writers who attempt this kind of fancy.

There are a few unfortunate, mostly mild, problems as with most books of this period, nothing too awful or offensive, but you have been warned. (Merritt is no Sapper or Sidney Horler, thankfully.) It stands as an Arabian filigree of romance, Gothic horrors, dream like qualities, and fancies that asks only that the reader be willing to surrender to it all, and still has its rewards if you do.