November 2011

Monthly Archive

Wed 30 Nov 2011

MARTIN SCOTT – Thraxas. Baen, paperback original; 1st US printing, September 2003.

Private eye novels come in all flavors and from all directions. Let me start with the opening paragraph or so, and you’ll see what I mean, and right away:

Turai is a magical city. From the docks at Twelve Seas to Moon Eclipse Park, from the stinking slums to the Imperial Palace, a visitor can find all matter of amazing persons, astonishing items and unique services. You can get drunk and swap tales with Barbarian mercenaries in the dockside taverns, watch musicians, tumblers and jugglers in the streets, dally with whores in Kushni, transact business with Elves in Golden Crescent, consult a Sorcerer in Truth is Beauty Lane, gamble on chariots and gladiators at the Stadium Superbius, hire an Assassin, eat, drink, be merry and consult an apothecary for your hangover. If you find a translator you can talk to the dolphins in the bay. If you’re still in need of fresh experiences after all that, you could go and see the new dragon in the King’s zoo.

If you have a problem, and you don’t have much money, you can even hire me. My name is Thraxas.

His sometimes assistant is a barmaid named Makri, a handy lass with a sword and prone to wearing a tiny chainmail bikini. This introductory volume in the United States actually consists of two novels as published in England: Thraxas and Thraxas and the Warrior Monks, and weighs in at a hefty 442 pages, in my opinion well worth your money at $7.99, and decidedly so if you’re still with me after reading that first paragraph above.

And I’ll leave the plots for you to discover on your own. The books are exactly what I am sure you think they are, and better. They’re funny, too. Since you can’t stop me, I’ll continue with some quotes from the second half of the book:

Makri lights a thazis stick, inhales a few times and passes it to me. I pour us a little klee. Makri’s eyes water as it burns her throat on the way down.

“Why do you drink this stuff?” she demands. “We’d have rioted in the slave pits if they’d tried serving it to us.”

“This is top quality klee. Another glass?”

“Okay.”

“…the Venerable Tresius lied about not meeting any other monks in the city. What if he’s really after the statue for his own temple and is using me to locate it for him? Wouldn’t be the first time some criminal tried to use me as a means of finding something. Wouldn’t be the tenth time in fact.”

“That’s what you get for being good at finding things.”

Makri wears both her swords, more or less hidden under her cloak, and slips a long knife into each of her boots. As usual, she is not entirely comfortable without her axe, but it’s too conspicuous. There is no legal reason why a woman can’t walk around Turai carrying an axe, but it isn’t exactly an everyday sight. A fully armed Makri — lithe, strong, and a blade sticking out in every direction — presents a very worrying sight for the Civil Guard. She tends to get stopped and questioned, which is inconvenient when we’re on a case. Also we get refused entry to high-class establishments.

I’ll stop here. Fantasy and the true detective novel don’t really mix — take for example the impossible crime of the missing two-ton statue, which no one saw being removed — utterly fantastic? Yes.

On the other hand, there is a fair-play clue involved, one that gives Thraxas the key to the case as soon as he hears it. That it lies in what he overhears a talking pig say means only that there’s more to the world than either you or I are apt to ever become aware of.

And there’s more to come!

— August 2003

The Thraxas novels —

UK editions:

Thraxas. April 1999.

Thraxas and the Warrior Monks. May 1999.

Thraxas at the Races. June 1999.

Thraxas and the Elvish Isles. August 2000.

Thraxas and the Sorcerers. November 2001.

Thraxas and the Dance of Death. May 2002.

Thraxas at War. July 2003.

Thraxas under Siege. May 2005.

Baen omnibus editions (US):

Thraxas. September 2003: Contains Thraxas and Thraxas and the Warrior Monks.

Death and Thraxas. August 2004: Contains Thraxas at the Races and Thraxas and the Elvish Isles.

Baen single novel editions (US):

Thraxas and the Sorcerers. June 2005.

Thraxas at War. February 2006.

Thraxas and the Dance of Death. July 2007.

Thraxas under Siege. August 2008

Wed 30 Nov 2011

REVIEWED BY WALTER ALBERT:

LIFE IN THE RAW. Fox, 1933. George O’Brien, Claire Trevor, Greta Nissen, Francis Ford, Warner Richmond, Gaylord (Steve) Pendleton. Based on the story “From Missouri” by Zane Grey. Director: Louis King. Shown at Cinecon 36, Hollywood CA, Aug-Sept 2000.

In Life in the Raw, described as an “odd concoction of Western and nightclub drama with some Russian atmosphere thrown in for good measure,” Clare Trevor made her feature film debut. “The first thing I was told,” Trevor recalled, was not to fall in love with my leading man. And then I immediately fell in love with George O’Brien.”

Trevor comes out West to join her brother (Gaylord Pendleton) who, unbeknownst to her, is involved in some very shady dealings. Before things are romantically resolved, O’Brien thinks she’s a baddie, and everyone thinks he’s one.

Trevor’s role doesn’t require her to do much except look great in tight-fitting western outfits, but O’Brien gets to do some pretend romancing with Greta Nissen and carry off a rescue scam that makes the last couple of reels fun to watch.

Mon 28 Nov 2011

ASSASSIN FOR HIRE. Anglo-Amalgamated Films, UK, 1951. Sydney Tafler, Ronald Howard, Katharine Blake, John Hewer, June Rodney. Director: Michael McCarthy.

Since this is an obscure British film of some 60 years in age, other than, of course, Ronald Howard, none of the names above meant anything before I watched this movie. Even afterward — even while noting that all of the participants were professionals through and through — I may be hard pressed to remember them the next time I come across them. (Ronald Howard was the star of the 1950s Sherlock Holmes series that made its way the US back then, so anyone of a certain age, as I am, should pick him out right away.)

He plays a Scotland Yard inspector in Assassin for Hire, an officious type who declares at the beginning that if the criminals don’t play by the rules, why should he? His eye in particular is on Antonio Riccardi (Sydney Tafler) whom he suspects is a hitman for anyone who cares to hire him. He is very good at what he does, including making sure that he has an ironclad alibi for every one of the extracurricular job he does.

Every criminal has a weakness, believes Inspector Carson, and Riccadi, by day a dealer in rare stamps, may have his in his brother, a classical violinist whose career he keeps under an iron thumb. Well, there’s no “may have†about it. The question is, how might the inspector take advantage of it?

This is a short film, just over an hour long, and it would have been ideal for an episode of the Alfred Hitchcock Hour on TV, say, with several twists along a way, mostly toward the ending. I will not tell you how many twists, for if I were to do so, you’d be counting along as you’re watching. (Of course I could tell you that there were three, say, with the third one being that there is no third one.)

There’s nothing here for any of the players to have built a career on, but it’s competently done, and if you were to find a copy on DVD, I don’t think you’ll begrudge the short time it would take you to watch it.

Mon 28 Nov 2011

EDWARD WRIGHT – Clea’s Moon. G. P. Putnam’s Sons; hardcover, April 2003. Berkley, paperback, 2004. Orion, UK, hardcover, 2003.

This retro-mystery set in late-1940s Los Angeles, a first novel by California-based writer, seems to have been published first in Great Britain, since it’s already won a Silver Dagger award given by that country’s Crime Writers’ Association.

It has a lot of the right ingredients going for it — starting with its former B-western movie star leading character, John Ray Horn — but as I’m sure I needn’t remind you, sometimes the whole is less than the sum of its parts.

The beginning is solid enough. Recently released from prison for a crime he did commit, no matter how justified, John Ray has been banned from the studios and has been forced to go to work as an enforcer for his former co-star, Joseph Mad Crow, an Indian who’s now the owner of a thriving casino.

The roles have been switched — a nice touch. John Ray is no longer the hero he once was, either on the screen as “Sierra Lane,” or in real life.

In fact, until he learns that his former stepdaughter has run away and disappeared, and he’s the one person who has the best chance of finding her, his life, in all likelihood, would have continued to slip away. Clea and her best friend Addie are girls on the verge of becoming women, and here lies a principal part of the puzzle that John Ray finds himself putting back together.

There is an analogy to be found here. The general Los Angeles area is a city on the verge of becoming a metropolis, a change that John Ray sees coming and finds lacking. Open space is disappearing, and housing projects are moving in.

All well and good. What’s more, some of the dialogue is reminiscent of Raymond Chandler, whose name you might be thinking right about now, a comparison not to be made lightly, and on occasion the resemblance is remarkable. The nightclub scenes are excellent, bringing pictures to mind some of the best of the film fare of the forties.

So what’s the problem? This is indeed Chandler country, strongly revisited, or at least it’s tiptoeing around it. But while John Ray is stalwart and strong, hard-boiled he’s not, and some of the decisions he makes are — well, let’s say they’re his own.

I also found the underlying theme of child pornography something less than savory. That’s primarily a personal reaction, I should add, but in terms of entertainment value, as far as I’m concerned, it’s a large empty hole I found hard to overcome.

The biggest disappointment, though, was, overall, the story’s amiable but eventual predictability, a trait in which Mr. Chandler, even without having the advantage of going first, never indulged. It’s a workmanlike effort, but when you read it — and if you’ve read this far, you definitely should — you’ll see what I mean.

PostScript: And in closing, let me ask you this. In almost every novel like this, why is it that everyone who smokes, lights up a Lucky?

The John Ray Horn series —

1. Clea’s Moon (2003)

2. While I Disappear (2004) [Shamus Award, Best Novel winner, 2005]

3. Red Sky Lament (2006) [Ellis Peters Historical Crime Award, UK, 2006]

[UPDATE] 11-28-11. A number of people I know, including Jeff Meyerson, who stops by here every so often, liked this book a lot more than I did. Even more telling, perhaps, Wright has won several awards for this series. Maybe I’m wrong — or I was, eight years ago. I dunno. Maybe I should put this at the top of my To Be Read Again list.

Sun 27 Nov 2011

A REVIEW BY RAY O’LEARY:

ERLE STANLEY GARDNER – Dead Men’s Letters. Carroll & Graf, hardcover, March 1990; softcover, July 1991.

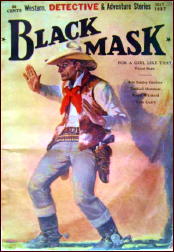

A collection of six Black Mask novelettes featuring one of Gardner’s early series characters, Ed Jenkins, known as the “Phantom Crook.”

Jenkins, though wanted in six states, cannot be extradited from California due to a legal technicality and this makes him a target of Police anxious to send him to Jail and other criminals who know that if they commit a crime with Jenkins in the area, he will get the blame.

The last three stories in the collection detail Jenkins’ duel with the crime boss of a California city and are sequels to “Laugh That Off,” the best story in the set. They center around Jenkins’ efforts to retrieve papers that would incriminate the dead father of a woman whom Jenkins loves but is unworthy of, which reminded me of an earlier “crook,” Hamilton Cleek, and his relationship with the woman he fell for.

As with most Gardner, Characterization and Dialogue are second-rate at best, but his deft way of turning a plot keeps one reading anyway.

One thing: I read someplace that Gardner first made his reputation as a Lawyer by championing the Chinese community, yet quite often here, he passes casually racist remarks towards Asians. Which raises the question, did a Black Mask writer, in order to be considered “hard boiled” have to espouse racist views?

Presumably, these sentiments couldn’t really be Gardner’s own. Or could they?

Contents:

Dead Man’s Letters. Black Mask, December 1926.

Laugh That Off. Black Mask, September 1926.

The Cat-Woman. Black Mask, February 1927.

This Way Out. Black Mask, March 1927.

Come and Get It. Black Mask, April 1927.

In Full of Account. Black Mask, May 1927.

Sun 27 Nov 2011

TWO TV WESTERN WHODUNITS

Reviewed by Mike Tooney

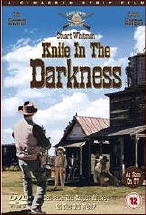

“Knife in the Darkness.” From the Cimarron Strip series (1967-68), Episode 18, January 25, 1968. Stuart Whitman (Marshal Jim Crown), Percy Herbert (Angus MacGregor), Randy Boone (Francis Wilde), Jill Townsend (Dulcey Coopersmith), David Canary, Philip Carey, Jeanne Cooper, Patrick Horgan, George Murdock, Tom Skerritt, Victoria Shaw, Karl Swenson, Grace Lee Whitney. Writer: Harlan Ellison. Music: Bernard Herrmann. Director: Charles R. Rondeau.

Since Jack the Ripper was never caught (at least publicly), it’s reasonable to speculate about what happened to him.

Science fiction maven Harlan Ellison chose to do some genre mashing with this script from Cimarron Strip, a relatively short-lived Western series (only one season of 23 episodes was produced). Ellison decided to have Jolly Jack (or someone who COULD have been the Ripper) immigrate to the United States and carry on his heinous activities — namely, slashing women to death.

For rugged and normally imperturbable Marshal Jim Crown, life is hectic enough without importing criminals from overseas, so when a local prostitute is murdered, Ripper-style, his nerves start to fray just a wee bit — as this exchange between him and inn keeper Dulcey Coopersmith (the delicately beautiful Jill Townsend) would indicate:

Dulcey: “You look worried — I can tell.”

Jim Crown: “I’m always worried when I work this town.”

Dulcey: “No, this is something special — this girl getting killed tonight.”

Jim Crown: “I told you when you came to Cimarron there’d be more killin’ than laughin’.”

As in England, the Ripper follows his usual M.O.: targeting women in the dark. Unlike most shows in this series, nearly the entire episode takes place at night and is nicely photographed with deep, rich shadows and feeble light sources. Bernard Herrmann’s musical score adds even more dimension to the story. (It’s been said that nobody could do ominous like Bernard Herrmann.)

And this episode features a marvelous cast, including character actors who earned fame in other TV venues: David Canary (Bonanza, 94 episodes), Philip Carey (Laredo, 56 episodes), Jeanne Cooper (The Young and the Restless, 894 episodes), Patrick Horgan (Ryan’s Hope, 27 episodes), Grace Lee Whitney (Star Trek, 8 episodes and several movies), plus versatile and ubiquitous Karl Swenson and George Murdock, and Tom Skerritt before he made the big time.

Ellison’s script and Charles Rondeau’s careful direction keep the viewer guessing, as suspicion continually shifts from one likely suspect to another.

“The Mind Reader.” From The Rifleman series (1958-1963), Season 1, Episode 40, June 30, 1959. Chuck Connors (Lucas McCain), Johnny Crawford (Mark McCain), Paul Fix (Marshal Micah Torrance), John Carradine (James Barrow McBride), Michael Landon (Billy Mathis), Sue Randall (Lucy Hallager), Vic Perrin (Ed Osborne), William Schallert (Fogarty), Robert Bice (John Hallager). Writer: Robert C. Dennis. Director: Don Medford.

John Hallager and Billy Mathis get into a real dustup over Hallager’s daughter, Lucy. So when Hallager is shot to death from ambush, Marshal Torrance, with reluctance, arrests Billy as the only one with sufficient motive.

However, Ed Osborne, the town drunk, knows the truth, and he’s running scared. He begins to panic when James Barrow McBride brings his mind reading act into town, claiming that, with time, he’ll be able to name any eyewitnesses to the crime. For Osborne, that would be fatal.

Lucas McCain is able to piece together the few clues available to him, enough in his mind to clear Billy but not enough to finger the actual killer. Then Lucy makes things worse by engineering Billy’s escape from jail, further incriminating young Mathis in Marshal Torrance’s eyes.

Lucas latches on to Osborne, in the fading hope that he’ll lead McCain to the murderer. The suspense in the last half of the show ratchets up very nicely, as Lucas bounces from one suspect to another. Finally, McCain figures out who the killer is — all of three seconds before he has to shoot him dead.

It’s pretty rare to have a genuine whodunit plot in a half hour Western, so kudos to writer Robert C. Dennis (1915-83) for this one.

Dennis had a long career of writing crime dramas for television. His credits are truly impressive: China Smith (12 episodes), The New Adventures of China Smith (12 episodes), Passport to Danger (10 episodes), Alfred Hitchcock Presents (30 episodes), Markham (4 episodes), M Squad (5 episodes), The Untouchables (6 episodes), Checkmate (6 episodes), 77 Sunset Strip (15 episodes), Perry Mason (22 episodes), The Wild Wild West (7 episodes), Hawaii Five-O (6 episodes), Dragnet: 1967 (19 episodes), Dan August (5 episodes), Cannon (6 episodes), Harry O (5 episodes), and Barnaby Jones (3 episodes).

Sat 26 Nov 2011

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

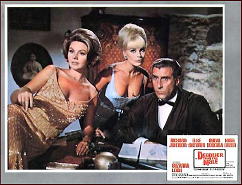

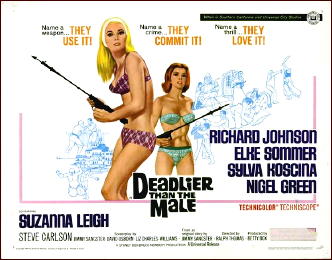

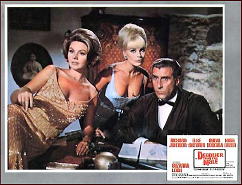

DEADLIER THAN THE MALE. Universal, 1967. Richard Johnson, Elke Sommer, Sylva Koscina, Nigel Green, Suzanna Leigh, Steve Carlson, Virginia North. Story & screenplay by Liz Charles-Williams, David D. Osborn & Jimmy Sangster, based on the characters created by Herman C. “Sapper” McNeile. Director: Ralph Thomas.

Compared to the Dick Barton film (reviewed here ), there’s nothing as pre-adolescent in Deadlier Than the Male, which is firmly adolescent in its imitation-Bond fantasies.

I must have seen this six times in my Senior year of High School, and I tried hard to convince my serious-film-student friends there was something really worthwhile there amid the sex, violence and Eastman Color. They told me that even I should be grown-up enough to reject this mindless rubbish, but it became available on video recently and I enjoyed it all over again.

This was the first Bulldog Drummond movie in about 20 years, and the producers approached it with B-movie gusto, garnished it with sexy assassins (Elke Sommer and Sylva Koscina, whose un-self-conscious bad acting seems quite fitting here), a scar-faced Chinese bodyguard, a giant chess game and Nigel Green’s droll villainy, all splashed across colorful locations tricked out with James Bond-style fights and wise cracks.

I have to agree with my old friends about its artistic merits, but the thing is infused with such a low-budget, gee-wouldn’t-it-be-fun-to-make-a-movie elan that if you haven’t read any good comic books lately, you might like it.

By the way, Bulldog Drummond is incarnated here by actor Richard Johnson, who also impersonated British Icons, Lord Nelson and Nayland Smith in films that were much less fun.

Sat 26 Nov 2011

Posted by Steve under

Reviews1 Comment

THE BACKWARD REVIEWER

William F. Deeck

PETER STORME – The Thing in the Brook. Simon & Schuster, hardcover, 1937; Mystery Novel of the Month #22, digest paperback, 1941, as The Case of the Thing in the Brook; Bonded Mystery #6, paperback, no date stated [1946], abridged.

Professor James Whitby, a biologist who is preparing a book on slime molds, discovers the dead body of a neighbor, the most hated man in the small community, hanging over a brook. It turns out that the man was strangled to death, had his brains bashed in, and then was hanged.

(Or maybe his head wasn’t bashed in; the coroner’s physician’s testimony and the summing up of the amateur detective at the end of the book conflict.)

Later on, the town drunk, who claims to have seen something strange at the time of the murder, is killed by having his head bashed in. He, too, was strangled, though not fatally, and had a noose put around his neck to simulate hanging.

Onto the scene comes Henry Hale, avid reader of mystery stories and would-be amateur detective. Since there are few physical clues, Hale uses “psychological patterns” to discover who perpetrated the crimes.

Though not a book anyone should seek out actively — it is not particularly well written and the characters are cardboard — it may be quite enjoyable for those who, in these cynical times, can accept the mores, views, and plot devices of the 1930s.

(For those who may be interested, Peter Storme is the pen name of Philip Van Doren Stern.)

— From The Poisoned Pen, Vol. 7, No. 1

(Whole #33), Fall-Winter 1987.

Bibliographic Data: This was the only appearance of amateur sleuth Henry Hale. Under his own name, Stern has one other entry in Crime Fiction IV by Allen J. Hubin: Love Is the One with Wings (Farrar, hc, 1951), reprinted as Manhunt (Berkley, pb, 1955).

Fri 25 Nov 2011

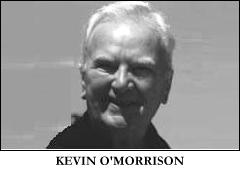

TV REVIEW AND SERIES HISTORY – CHARLIE WILD, PRIVATE DETECTIVE (1950-1952)

by Michael Shonk

As a long time fan of radio’s Adventures of Sam Spade, I have wanted to sample an episode of Charlie Wild for over forty years. While there are no known surviving copies of the NBC or CBS radio show I have found an available DuMont TV episode online at tv4u.com. [Scroll down to the Charlie Wild photo and link.]

But before we get to my review let’s examine the history of Charlie Wild, Private Detective (aka Charlie Wild, Private Eye).

In radio and early television, the networks sold time slots to advertisers. Wildroot Hair Tonic paid through Batten, Barton, Durstine & Osborn ad agency to NBC for the Sunday 5:30pm half hour slot to air Adventures of Sam Spade. The series was popular with radio listeners and critics, but there were growing problems. Wildroot decided to drop the series.

Broadcasting (September 25, 1950) reported over 6,000 letters requesting Sam Spade remain on the air. Wildroot and BBD&O denied the listing of star Howard Duff in “Red Channels” as a possible communist was the cause. They claimed it was due to the need for a lower budget so Wildroot could increase its spending in television.

When Wildroot dropped Spade, it had also reduced the time slots they owned from two to one. Producer-director William Spier, who owned a piece of Sam Spade radio series, confirmed there had been an attempt to budget radio and TV versions of Sam Spade, but no agreement could be reached.

“WILDROOT DROPS ONE DICK, PICKS ANOTHER PRIVATE EYE. Wildroot, which recently dropped Sam Spade, last week bought Charlie Wild, Private Eye, for its Sunday afternoon time on NBC.” (Billboard, September 9, 1950)

NBC RADIO. September 24, 1950 through December 17, 1950. Sunday 5:30-6pm (E). 13 episodes. George Petrie as Charlie Wild. Written by Peter Barry. Directed by Carlo D’Angelo. Produced by Lawrence White.

Broadcasting (August 28, 1950): “Wildroot Co, Buffalo will sponsor agency-created program titled Charlie Wild, Private Eye…”

In Billboard (October 7, 1950), reviewing the first radio episode of Charlie Wild, Leon Morse wrote, “Cut from the Sam Spade pattern with all the familiar ingredients, this detective series should also establish itself with the aid of some sharper scripting.” Morse found “George Petrie’s acting of the private eye was slick and smooth…”

While Charlie was a rip-off of Spade, Charlie was not Sam. It was Sam Spade (Howard Duff) who introduce Charlie Wild (George Petrie) to the radio audience, according to Spade historian John Scheinfeld. Also Sam and Charlie were both on NBC radio (Spade on Friday and Wild on Sunday) November 17th through December 17th.

Wildroot wanted Charlie Wild on TV as well as radio.

December 2, 1950 Billboard reported, “NBC’s loss of the $500,000 Wildroot radio billings for Charlie Wild, and half again as much for the projected TV version, was the direct result of the web’s being in such healthy shape in TV. Because NBC-TV could not provide the sponsor with a time slot for the new video version, Wildroot approached CBS-TV. That net agreed to take the business- if the radio version switched from NBC too. Total gain for CBS – about $750,000.”

CBS RADIO. January 7, 1951 through July 1, 1951. Sunday 6-6:30pm (E). Weekly. 26 episodes.

CBS TELEVISION. December 22, 1950 through April 6 (or 13), 1951. Friday 9-9:30pm (E). Alternate weeks.

— April 18, 1951 through June 27, 1951. Wednesday 9-9:30pm (E). Weekly.

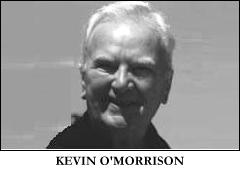

Charlie Wild played by Kevin O’Morrison (December through March), John McQuade (March 1951 through rest of series). Sponsored by Wildroot Company Inc through BBDO via CBS. Produced by Lawrence White and Walter Tibbals for Regis Radio. Written by Peter Barry. Directed by Paul Nickell.

The Billboard (January 6, 1951) review of the Charlie Wild, Private Detective TV premiere found that “O’Morrison was sufficiently engaging tele-wise as redoubtable Wild.” Reviewer Bob Francis also wrote, “What Wild needs is more original story approach and less hokum.”

Dates get confusing for the television series (perhaps some strong brave TV Guide collector could save the day). While the TV series aired on alternate Fridays, the radio series was weekly and on Sunday. It appears there were more radio episodes produced than television.

In the June 9, 1951 issue of Billboard, “…the cancellation this week of the simulcast version of Charlie Wild, Private Eye on Columbia Broadcasting System’s radio & TV networks by Wildroot… Wildroot brought Charlie Wild over from NBC, but the program failed to catch on sufficiently to make for renewal.”

That was the end of Wildroot’s involvement with Charlie, as well as the end of Charlie on radio, but it was not the end of Charlie Wild. Billboard (August 11, 1951) reported Mogen David Wine Corporation of America through agency Weiss & Geller decided to sponsor Charlie Wild and moved him to ABC-TV.

ABC TELEVISION. September 11, 1951 through March 4, 1952. Tuesday 8-8:30pm (E). Larry White Productions. Executive produced by Herbert Brodkin. Produced by Larry White. John McQuade as Charlie Wild.

In a Billboard (September 22, 1951) review of episode “The Case of the Sad Eyed Clam” written by Stanley Niss and directed by Leonard Valenta, critic Haps Kemper wrote, “Clam’s plot was routine, the script hardly scintillating, and the performances unenthusiastic…”

ABC was having major financial problems and was trying to convince the FCC to approve ABC’s desire to merge with United Paramount Theatres. (DuMont was the chief opposition. For more about that story read Billboard March 1, 1952, page 6.) Many of the advertisers panicked and removed their programs from ABC. Mogen David took Charlie Wild to DuMont.

DUMONT TELEVISION. March 13, 1952 through June 19, 1952. (*) Thursday 10-10:30pm. DuMont Presentation in association with L. White and E. Rosenberg Production. Sponsor was Mogen David Wine

(*) According to Broadcasting (July 7, 1952), Charlie was still on the DuMont schedule in July. The Los Angeles Times had Charlie airing on KTTV-TV Los Angeles at Thursday 8:30-9pm (P) as late as July 31, 1952.

“The Case of Double Trouble.” Cast: John McQuade as Charlie Wild, John Shellie as Captain O’Connell, Philip Truex as Tillinghost, Philippa Bevans as Amanda. Produced by Herbert Broadkin. Directed by Charles Adams. Written by Palmer Thompson. Television director was Barry Shear.

This was DuMont so it is no surprise the production values were cheap. Shooting live and in small sets limited the possibilities for action, forcing the story to rely too heavily on the weak dialog and disappointing cast. John McQuade performance as Charlie was lackluster.

We open as Charlie is talking into a Dictaphone to “Sweetheart.” He tells her about “The Case of Double Trouble.” It began when Charlie’s pal Police Captain O’Connell found an envelope outside Charlie’s door. The Captain and Charlie plan to have dinner together. The envelope contains half of a five hundred dollar bill and a promise for the other half when Charlie takes a unknown client’s case.

It is late Friday and despite a hungry Captain tagging along, Charlie meets the client. The client wants Charlie to protect a priceless parchment in a sealed envelope for the weekend. Charlie takes the envelope back to his office where he is knocked out by a huge ruthless woman and her pipsqueak husband.

Charlie wakes up and calls O’Connell who is still waiting for his dinner. Charlie tells his pal to go up to the client’s hotel room and keep him there until Charlie can get there.

Soon, all the characters gather in the room, there is a required fight, and all is revealed. We end back with Charlie on the Dictaphone telling “Sweetheart” there is money in the safe minus what he and the Captain spent on dinner.

“Get Wildroot Cream Oil, Charlie/It keeps your hair in trim/You see it’s non-alcoholic, Charlie/It’s made with soothing lanolin…”

One of my goals, with these research heavy reviews, is to focus on the source materials of the time the series was made in an effort to confirm or disprove the current historical views which too often is riddled with misinformation. There remains questions about Charlie Wild I was unable to confirm or disprove.

Did the series title come from the Wildroot commercial jingle that advised Charlie to get the hair product? Probably. Oddly, each of the Billboard’s reviews discussed the commercial but made no mention of any connection between the series title and the commercial jingle.

What role did Dashiell Hammett’s character, Sam Spade’s secretary Effie Perrin play in Charlie Wild? I find it hard to believe Wild’s secretary and Spade’s secretary was the same character. I found no mention of Wild’s secretary by any name, not even in the reviews. Try reviewing radio’s Sam Spade without mentioning his secretary.

Currently, it is unknown who played Charlie Wild’s secretary in the NBC radio series. It is commonly accepted today that Cloris Leachman played TV’s Charlie Wild’s secretary Effie Perrin.

Hopefully, someday a copy of the NBC radio Charlie Wild with George Petrie (who would have been a better replacement for Howard Duff as Sam Spade than Steve Dunne) will be found. I wonder what reaction the audience (to say nothing about the lawyers) had if Effie Perrin was Wild’s secretary in New York on NBC, Sunday at 5:30pm and Sam Spade’s secretary in San Francisco on NBC, Friday at 8:30pm.

There remain fifteen Charlie Wild TV episodes at the UCLA Film and Television Archive, as well as some at the Paley Center. These could hold the answer about Effie, if she did not spend all of her time off stage as she did in “The Case of Double Trouble.” Was Charlie Wild’s secretary Effie Perrin or, as I suspect, another character called Effie?

ADDITIONAL SOURCES:

On the Air: The Encyclopedia of Old-Time Radio by John Denning.

JJ Radio logs: http://www. jjonz.us/RadioLogs

Mystery*File: https://mysteryfile.com/blog/?p=8425

Fri 25 Nov 2011

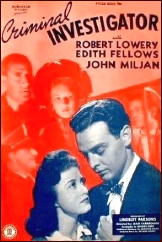

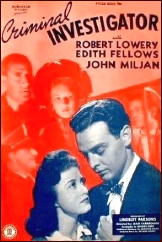

CRIMINAL INVESTIGATOR. Monogram Pictures, 1942. Robert Lowery, Edith Fellows, John Miljan, Jan Wiley, Charles Jordan, George O’Hanlon, Vivian Wilcox. Director: Jean Yarbrough.

There are a few reasons to watch this terrifically inept murder mystery movie, but the plot is not one of them. In recent months I’ve come to enjoy Robert Lowery’s performances, and seeing juvenile star Edith Fellow’s last movie before her comeback in television in 1949 comes as a distinct pleasure as well. (She was Polly Pepper of Five Little Peppers fame, for example, as well as one of Mrs. Wiggs children in the Cabbage Patch movie.)

Lowrey’s a brash newspaper reporter in this movie, but he got the job only because his father is the commissioner and he has it only until he messes up, which his editor suspects is going to be right away. But luckily Bob Martin (that’s Lowery), college grad, knows sign language, which he uses to talk to a formerly uncommunicative prisoner after sneaking his way into jail to interview him. Unlucky for him, though, the guy behind the bars pulls a fast one, and uses a phony story to send a message in code to his lawyer.

Why the elaborate scheme? Don’t ask. Martin’s next assignment is even more mind-boggling. He arrives too late to see Joyce Greeley being released from prison on parole, and she ends up dead, dumped on a suburban lawn and found by Martin as he nonchalantly walks by. Who’s Joyce Greeley, you ask? None other than the girl who was the subject of the coded message in the previous paragraph.

Wait, wait, there’s more. Martin then happens across the dead man’s sister (Edith Fellows) in the bus station waiting for his sister to show up. Totally by accident, of course, and the sister has no idea why the bad guys are after her, nor even that her sister was in jail. (A propos of nothing, Ellen Farrell was at least a foot shorter than Robert Lowery, but they do make a good team together.)

Some of the action takes place in a theater where a musical revue is being rehearsed, which gives Jan Wiley a chance to sing a couple of songs while some long-legged beauties show off their talents in the background.

I’ll give this movie two stars (out of ten) and give you a break by telling you no more about the plot, which I admit had some promise, but as you know full well, not all promises are always kept.

Next Page »