February 2011

Monthly Archive

Mon 28 Feb 2011

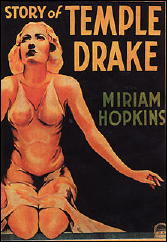

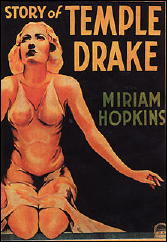

THE STORY OF TEMPLE DRAKE. Paramount Pictures, 1933. Miriam Hopkins, William Gargan, Jack La Rue, Florence Eldridge, Sir Guy Standing, Irving Pichel. Based on the novel Sanctuary, by William Faulkner. Director: Stephen Roberts.

I don’t know about you, but I like to know as little about a movie before watching it as I can. Most of the time you can’t help but knowing something about a movie – you’ve read a review, somebody’s recommended to you, or it was based on a story or a character you’ve already read or heard about it.

None of the above this time. It came in a white envelope along with 20 or so others I’d bought from a dealer specializing in classic (old) detective and crime noir films, and that’s all. I didn’t know what year it was made, who was in it, that it was based on a William Faulkner novel, and if I’d have known that it was Sanctuary, it wouldn’t have made any difference to me, since that’s a novel I’ve never read.

But here’s the shameful truth. William Faulkner and I had a bad experience together back in high school English class. It wasn’t his fault. Silas Marner and Pip and all their adventures had the same problem. If they wanted me to read it, I wasn’t interested. All I wanted to do was to use determinants to solve systems of three or more simultaneous linear equations.

Miriam Hopkins is the star. She’s the one who plays Temple Drake, the spoiled granddaughter of the town judge, a southern belle whom in high school we’d have called a – well I won’t say the word, but her dates always seem to end with the male half panting and wanting more.

She has an evil streak in her, she admits to Stephen Benbow (William Gargan) who has been in love with her for a long time and has asked her to marry him, but as many times as he has asked, she has turned him down. By profession, Bendow is a local attorney whom the judge calls upon to defend penniless clients in his jurisdiction.

I’ll make this shorter, perhaps. Temple Drake, on yet another date gone bad, is kidnapped by a local gang of bootleggers hanging out in a decaying Southern mansion, and in doing do, catches the eye of the Trigger (the vicious and malevolently evil-looking Jack La Rue), head of the gang.

She witnesses the cold-blooded murder of the young lad guarding her at night, is raped by Trigger (a scene not seen but oh so strongly suggested), and forced into a privileged life of prostitution (again only suggested but everyone in the audience knows exactly what is going on).

There is more to come, but the purpose of a review is not to tell the whole story, but to give you a sense of the story, if you should so want one (see above), and the fact that Benbow is a public defender is important. The concluding trial scene is as tense and moving as anything I’ve seen in a movie in quite a long while.

It’s also a movie that should be much better known than it is, and perhaps it will be soon. If I’ve intrigued you enough – if you’ve read this review all the way to here – for now, the only way you can watch this film is from one of those online dealers that sell old movies in white envelopes with only the name of the movie on them.

[UPDATE.] Later the same day. Since writing this review, I’ve done some browsing on the Internet, and from what I’ve read, this pre-Code movie did not last long in the theaters when it was first released. It was, rather, one of the straws that brought the Hays Office into being. I am not surprised.

Its notoriety, however, and the fascination of today’s audience for pre-Code films means that it may be more well-known than I’d thought. There’s still no official DVD release for Temple Drake, but it’s been shown recently at several film festivals that specialize in old and otherwise forgotten films such as this one, and a good print is said to exist. Thank goodness for film fanatics!

[UPDATE #2.] 03-01-11. Todd Mason has included this as one of this week’s Overlooked Films on his blog. For the others, follow this link.

Dan Stumpf’s comment about the “nightmarish feel [of] Temple’s night at the farm house” is a perfect description. Once seen, you won’t forget it. It also reminded me that I’d temporarily misplaced one of the images I meant to include. I’ll add it here:

Sun 27 Feb 2011

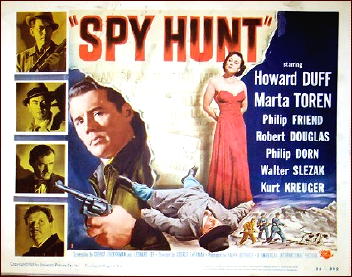

SPY HUNT. Universal International, 1950. Howard Duff, Märta Torén, Philip Friend, Philip Dorn, Robert Douglas, Walter Slezak, Kurt Kreuger. Based on the novel Panthers’ Moon by Victor Canning. Director: George Sherman.

When a young woman (Märta Torén) posing as a journalist slips some vital information on microfilm into the collar of one of two rare black panthers that Steve Quain (Howard Duff) is taking from Milan to the United States – they are in fact his ticket back home, as he is otherwise flat broke – it’s the beginning of a fine tale of not so much espionage but high adventure in the heart of postwar Europe.

When the railroad car that Quain and the panthers are in is separated (intentionally) from the rest of the train, it crashes somewhere in the Swiss Alps. When Quain awakes, he is in bed in a ski area hotel, and the panthers are loose.

On the scene are a small but significant number of suspicious characters: a newspaperman, a big game hunter, and an artist, and the hunt is on. But who’s the one who’s after not the panthers but what’s in the male panther’s collar?

So hunting the down the spy is where the title comes from, but if you were to ask me, I think that they wasted a perfectly good one in Panthers’ Moon, the book by Victor Canning this movie is based on. The panthers play their part very well [FOOTNOTE], but so does Howard Duff, even though his voice and slightly perplexed speech patterns sound exactly like that fellow on the radio. Sam Spade – that’s the one.

Equally effective as essentially the only female character in this movie is the dark-haired and very pretty Swedish actress Märta Torén, whose several other American movies I am in the process of tracking down, many of them in the same noir or near noir category that this one’s in — that’s how great an impression she made on me. (Other the other hand there is a long list of female movie stars I say the same thing about. Fickle, I am.)

Märta Torén married writer-director Leonardo Bercovici in 1952 and the final few films in which she appeared were made in Italy. She died in 1957, only 31 years old.

FOOTNOTE. The black panthers were played by a pair of mountain lions who were dyed black for the film.

Sun 27 Feb 2011

REVIEWED BY MICHAEL SHONK:

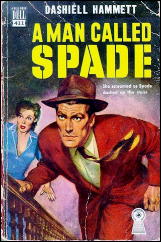

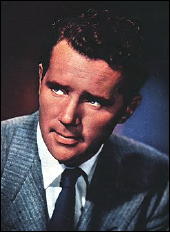

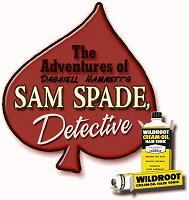

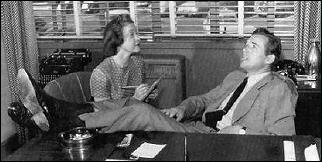

THE ADVENTURES OF SAM SPADE, DETECTIVE. ABC: July 12, 1946 through October 4, 1946. CBS: September 29, 1946 through September 18, 1949. NBC: September 25, 1949 through September 17, 1950; November 17, 1950 through April 27, 1951. Based on characters created by Dashiell Hammett. Produced and directed by William Spier. Cast: Sam Spade: Howard Duff (July 12, 1946 through September 17, 1950), Steve Dunne (November 17, 1950 through April 27, 1951), Effie Perrine: Lurene Tuttle. Announcer: Dick Joy

The Adventures of Sam Spade, Detective was popular with the radio audience and critics alike. While today it is rightfully remembered for its humor and style, the show featured great radio mysteries and moments of drama.

In “Vafio Cup Caper” (August 22, 1948), Sam chases a priceless ancient Greek cup in a mystery with non-stop twists and hilarious dialogue.

In “Edith Hamilton Caper” (April 17, 1949), Sam falls for a woman he believes killed her husband. The episode was dramatic with an effective use of music. Effie’s support for broken-hearted Sam was typical of a series that could be tearfully sad, yet end with a bitterly funny line.

Sam Spade changed when he moved to radio. Howard Duff took Bogart’s cynical loner and let him have fun. Duff’s Spade could get drunk, be short-tempered, and sleep with the femme fatale, and we would be as forgiving and admiring as his secretary Effie.

Some of radio’s top talent worked on the series.

Producer/director William Spier was famous for his popular and critically acclaimed series, Suspense. To promote Sam Spade, Spier aired an hour-long episode “The Khandi Tooth Caper,” a sequel to The Maltese Falcon, on Suspense (January 10, 1948).

Lurene Tuttle (Effie), known as “Radio’s First Lady,” was as important to the show’s success as Howard Duff. Top radio actors would appear, often without billing. Some of the supporting cast were William Conrad, June Havoc, and Hans Conrad.

Behind the mike talent was equally impressive. Jason James (Jo Eisinger) and Bob Tallman won the Edgar award for Best Radio Drama in 1947. Other writers included Gil Doud, E. Jack Newman, and Elliott Lewis.

While Hammett had no direct involvement, the writers made good use of other Hammett characters such as in “Dick Foley Caper” (September 26, 1948). Sam tries to help an old friend from the Continental Detective agency. A highlight was when Sam told the femme fatale he knew she had a gun because it made her bulge in the wrong place.

The series did adapt some of Hammett’s short stories. “Death and Company” (August 9, 1946) was adapted from a Continental Op short story with the same title. While no recording survived, the script is reprinted in the book The “Lost” Sam Spade Scripts, edited by Martin Grams, Jr.

It would take outside forces to kill the show. Hammett was blacklisted and his name removed from the credits. When Howard Duff’s name appeared in “Red Channels”, the series sponsor, Wildroot Creme Oil Hair Tonic, canceled the series and replaced it with Charlie Wild, Private Detective (NBC: September 24, 1950 through December 17, 1950. CBS: January 7, 1951 through July 1, 1951).

According to Spade expert John Scheinfeld, the last words Duff said on radio for six years was as Spade welcoming Charlie Wild to the PI business. The only thing Charlie and Sam had in common was a secretary named Effie Perrine. No recordings of the radio show exist and who played Effie on radio’s Charlie Wild remains unknown.

Sam Spade was not off the air long. The radio audience demanded the show back and NBC quickly obeyed. The only change in the series had Steve Dunne take over the role of Sam Spade, but it was a change that cost the series its charm.

Duff had a light playful touch while Dunne’s delivery seemed forced, often sounding like a bad Jack Benny impersonator. Times were changing. Duff’s Spade was a lovable drunken womanizer, Dunne’s Spade was becoming a boy scout.

The final episode “Hail and Farewell” (April 27, 1951) was an average melodrama about saving an innocent man from execution. At the end Spade told listeners to write in and save the series. But this time the Governor did not call.

So, after over two hundred and forty episodes (around seventy are known to still exist on recordings), it really was “Goodnight Sweetheart.”

SOURCES:

â— On the Air: The Encyclopedia of Old-Time Radio, by John Dunning

â— Radio Detective Story Hour podcast: Jim Widner (otr.com/blog)

â— Boxcars 711 podcast: Bob Camardella (boxcars711.podomatic.com)

â— Sam Spade Double Feature, Volume 1. Audio Archives: Bill Mills (audible.com)

â— OTRR.org

â— Digital Deli (digitaldeliftp.com)

â— MP3 disk with sixty seven episodes of Sam Spade, the Suspense episode “Khandi Tooth Caper”, and other extras. (otrcat.com)

There are many places where you can still find Sam Spade on the web, as well as iTunes and the Sirius XM radio series “Radio Classics.”

Sat 26 Feb 2011

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

UNFORGOTTEN CRIME. Republic Pictures, 1942. Originally released as Affairs of Jimmy Valentine. Dennis O’Keefe, Ruth Terry, Gloria Dickson , Roman Bohnen, George E. Stone, Spencer Charters, Roscoe Ates. Based on the play Alias Jimmy Valentine by Paul Armstrong (1910). The play itself was based on O. Henry’s short story “A Retrieved Reformation,” Cosmopolitan, April 1903. Director: Bernard Vorhaus.

Unforgotten Crime [the title under which it was shown on TV] is a rare gem, a film that takes all the standard elements of the “B” feature and works them into a surprisingly thoughtful new form.

Dennis O’Keefe is the brassy radio reporter whose promotional scheme involves ferreting out the notorious Jimmy Valentine, a once-notorious cracksman now living under an assumed name in a small town (Roman Bohnen). When he offers a reward to the first one who finds Valentine, the town goes wild with outsiders in search of fortune vs. steady townsfolk suddenly suspicious of each other and consumed by their own greed.

Through all of this, the old dependable B-movie types walk through their fusty paces with a familiarity that borders on contempt: Pretty Ingenue, Dumb Cop, Bumbling Sidekick, Wisecracking Female Reporter, Cute Kid, etc. etc, played by old dependable character actors like Ruth Terry, Roscoe Ates, George E. Stone and Gloria Dickson.

Then something weird happens: They start acting like Real People; it’s like The Purple Rose of Cairo, where the characters abandon the story and start pursuing their own interests, and it makes for a fascinating bit of Cinemah.

I should mention that Unforgotten Crime, the copy I have, suffers from more than a few continuity gaps and sudden jumps, the result of being cruelly cut from its initial running time (seventy-four minutes, rather lengthy for a “B,” to a convenient-for-TV 54 minutes) and never restored.

Editorial Comment: There are two copies of this film offered for sale on Amazon, both under this title. One lists the running time as 52 minutes, the other doesn’t say, but since it’s the TV title, I suspect that it’s also the abbreviated version. (I recently purchased a copy offered by a collector-to-collector seller under the Jimmy Valentine title, but I have yet to watch it. Hopefully it is the longer version.)

Sat 26 Feb 2011

Posted by Steve under

ReviewsNo Comments

REVIEWED BY BARRY GARDNER:

EMMA LATHEN – Right on the Money. John Putnam Thatcher #22. Simon & Schuster, hardcover, 1993. Harper, paperback, 1995.

A back cover blurb from the Washington Post says, “Still spoofing Wall Street with wild hilarity.”

Makes you wonder what they were reading, or who. Spoof? Maybe a little, but not much. Wild hilarity? Emma Lathen? I hope this person never reads Westlake, or they’ll have to carry him/her to the hospital, or the morgue.

A large corporation wants to merge with a small, family owned company, and for reasons of their own, the owners of the small company are agreeable. John Putnam and his bank, the Sloan, are bankers for the smaller firm, and as the get acquainted talks begin.

Ken Nicols, a Sloan employee who has appeared increasingly in the series, is assigned to participate. A junior manager at the larger company is trying to disrupt the proceedings for his own reasons. Then a fire occurs at the small company, destroying many records, and then the troublemaker is found murdered at a trade show at which both companies were present.

Lathen’s view of business finally seems to be reflecting the 80s and 90s a bit. As in all her books, we get thoroughly acquainted with all the players on both sides of the equation, and with the businesses they are engaged in. Thatcher as usual appears sporadically during the course of the book, but also as usual, provides the final solution.

I’ve always liked the Thatcher books, and still do. Though they aren’t deep, they’re amiable and well-written. But wild hilarity, now … gimme a break, okay?

— Reprinted from Ah, Sweet Mysteries #9, September 1993.

Fri 25 Feb 2011

Reviewed by DAVID L. VINEYARD:

TRUE TO LIFE. Paramount Pictures, 1943. Mary Martin, Franchot Tone, Dick Powell, Victor Moore, William Demarest, Mabel Paige, Ernest Truex, Clarence Kolb. Director: George Marshall.

Delightful George Marshall screwball comedy with Powell and Tone radio soap opera writers who have hit a dry spell and are facing an angry sponsor (Clarence Kolb) who want to cancel the continued adventures of Kitty Farmer. Powell goes out in the rain looking for inspiration and meets Mary Martin in a diner where she mistakes him for a homeless guy out of work because he left his wallet at home.

She brings him home to meet eccentric dad Victor Moore who is constantly tinkering with nonsensical inventions; Uncle William Demarest, a grouch who can’t (or won’t) work (Mom: Now you’ve hurt his feelings. Pop: They never seem to bother him at the dinner table); Mom, Mabel Paige, who has no patience with the new out of work addition to the family; a little brother who wants to be doctor and keeps asking people for blood; and little sister who has hit puberty at about 90 miles per hour and has eyes for the new boarder.

Using the family for their inspiration Powell and Tone have a hit on their hands, and Powell moves in with the family to get more inspiration, but Tone gets suspicious, and posing as a playboy, he begins to move in on Mary Martin.

Meanwhile Powell has to keep the family from hearing the radio program and is forced by suspicious Mom to take a job at the bakery with Pop. And keeping the family from hearing the program gets harder and harder, especially when they do hear the show and notice how close it is to their everyday life — right down to the dialogue.

The usual complications ensue. Martin tries to get Tone to hire Powell, and Demarest finds out Powell has been sabotaging the family’s radio to keep them from listening to the broadcast and figures out what they boys are up to.

Fame sits well with the family who find themselves on easy street — Moore even puts Demarest to work at the bakery — but Martin doesn’t like her new family and Moore puts his foot down to bring Martin and Powell together for the finale, turning the tables on Powell and Tone with the help of their director Truex.

While not a musical, Martin sings “Mister Pollyanna,” and Powell does likewise for the memorable Hoagy Carmichael and Johnny Mercer tune “The Old Music Master,” and “There She Was,” a more typical Powell tune.

Marshall was one of the masters of the screwball school and with this cast could hardly fail. While only mildly satirical, Powell is fine, Martin lovely and feisty, Tone good in his usual second lead mode (even breaking the fourth wall in the final scene), and Victor Moore delightful — especially in conflict with Demarest and browbeaten by Paige.

In addition its interesting to see Powell in transition from this boy crooner to the mature screen persona that blossomed with Murder My Sweet three years later, and begun in Preston Sturges 1940 film Christmas in July.

You do have to wonder, though, if most radio writers were pulling down a $1,000 a week and sharing a penthouse apartment and a valet in 1943 New York.

Fri 25 Feb 2011

TIMES SQUARE PLAYBOY. Warner Brothers, 1936. Warren William, June Travis, Barton MacLane, Gene Lockhart, Kathleen Lockhart, Dick Purcell. Screenplay by Roy Chanslor based on the play “The Home Towners†by George M. Cohan. Director: William C. McGann.

With a running time of only 62 minutes, Times Square Playboy still seemed to last three times as long as it should have, at least if you ask me, and if you’re reading this, you might as well be. Although I didn’t time it precisely, I’d say it’s fifteen minutes for sure before there’s an inkling of what the story’s about.

And I’ll make this summary as short as I can. A fellow from Big Bend back home, Warren William, has come to the big city — New York City, to be precise – to make good, and make good he has. And at the age of 40 he’s found the girl he wants to marry (June Travis), who’s currently working as a singer at hot spot night club.

When his best man (Gene Lockhart) comes to town, the latter comes to the immediate conclusion that the new bride and her whole family are a bunch of chiselers ready for the kill, which is to say to sponge off William for the rest of their lives. To make things worse, he tells the groom-to-be so, and in no uncertain terms.

The two of them fight, the bride-to-be and her family are told off, they storm out … and the best man has some planning to do before the wedding is back on again. Two and a half paragraphs and I’ve told you everything. Even My Little Margie sitcoms had more story to them than this.

When I think of Warren William, I think of a classy but solidly rigid fellow — aristocratic if not out-and-out patrician.

He’s certainly that in this movie, but in Playboy he’s also given a butler-cum-valet (Barton MacLane) who as part of his duties engages his employer in down-to-earth wrestling matches to try to soften his image up a little. It’s a good try, but MacLane seems to fit his part better than William does.

June Travis made 30 movies in four years (1935-1938) and even her good brunette looks and broad grin of a smile didn’t mean that she made many movies with more of a B-budget than this one, which is a shame. (She did play Della Steet in one of the Perry Mason movies.)

A short simple plot, though, I have to admit, isn’t a crime. But a comedy that isn’t funny might as well be. I got the wrong vibes from this one. I think Lockhart’s accusations could have hit an accurate target just as easily as not, and if so, then where would this movie have gone?

Fri 25 Feb 2011

REVIEWED BY STAN BURNS:

MURDER BY INVITATION. Monogram, 1941. Wallace Ford, Marian Marsh, Sarah Padden, Gavin Gordon, George Guhl, Wallis Clark, Minerva Urecal, J. Arthur Young, Herbert Vigran. Director: Phil Rosen.

This Monogram mystery (calling it a B movie would be kind) is another entry in the “dark old house” genre. Reporter Bob White (Wallace Ford) investigates a series of murders at a spooky old house full of secret passages, sliding pictures, greedy relatives, and eyes looking secretly into the room.

I kept expecting to see Abbot and Costello walk through the door at any moment. Rich Aunt Cassandra’s relatives dragged her into court and tried to have her declared incompetent so that they could gain control of her fortune, but the judge found in her favor even though she likes vinegar on her apple pie.

So she invites all her relatives spend a week with her at her country mansion so she can decide which one will get the bulk of her estate. But no sooner do they arrive at midnight than one of them is stabbed to death (“She must have seen The Cat and the Canary,” quips White’s secretary when she hears about the midnight invitation).

When reporter White arrives with his secretary and photographer he is welcomed into the murder scene (yes, a fantasy film…). No sooner does he arrive than the body disappears and another one appears in its place, and then that one disappears also.

(In an aside Wallace Ford addresses the audience and says that you know you are past the halfway point in a mystery movie when the bodies have disappeared — and this movie is more than half over).

This is a really goofy movie, not to be taken seriously, but fun to watch. At the end as Bob White starts a long, long kiss with his secretary, the camera pans over to Eddie the photographer and he says something like “The Hays Office isn’t going to like this…”

Rating: C minus.

Fri 25 Feb 2011

REVIEWED BY WALTER ALBERT:

THE STOLEN VOICE. World Film Corp., 1915. Robert Warwick, Frances Nelson, Giorgio Majeroni, Violet Horner, Bertram Marburgh. Screenwriter/director: Frank Hall Crane. Shown at Cinefest 28, Syracuse NY, March 2008.

When society matron Belle Borden (Violet Horner) is entranced with the world-famous tenor Gerald D’Orvilie (Robert Warwick) her jealous suitor, the sinister mesmerist Dr. Von Gahl (Giorgio Majeroni) renders D’Orville mute.

Belle immediately loses interest in the silenced tenor, who travels abroad, exhausting all of his fortune in an attempt to recover his voice. Reduced to utter penury, Gerald is rescued by someone he once salvaged from the refuse heap of humanity, rising to new heights as a silent screen star. When Dr. Van Gahl sees Gerald in his new-found glory on the screen he has a fatal heart attack, which immediately restores Gerald’s voice.

I’ve skipped over several interesting features of which the most striking is the rescue by Gerald of his co-star from the raging rapids which are pulling her to a violent death. But you’ll get no more details from me. I’ve whetted your appetite enough already. (By the way, I loved the film. Or hadn’t you guessed that already?)

Editorial Note: Robert Warwick’s movie and television career began in 1914 and did not end until 1962, two years before his death, with a substantial combined 242 total credits on bot screens. Moviewise, his roles seem largely to have consisted of minor roles in bigger films, and bigger roles in B-movies.

Catching my eye, though, looking down through the list of movies he appeared in, are several he made for Preston Sturges in the early 1940s: The Great McGinty (1940), Christmas in July (1940), The Lady Eve (1941), and Sullivan’s Travels (1941). He was third-listed in the latter, after Joel McCrea and Veronica Lake.

Fri 25 Feb 2011

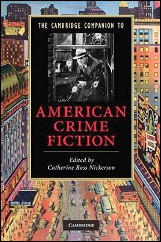

The Murder of Mystery Genre History:

A Review of The Cambridge Companion to American Crime Fiction

by Curt J. Evans

On the back cover of The Cambridge Companion to American Crime Fiction (Cambridge University Press, 2010; Catherine Ross Nickerson, editor), the blurb tells us that the fourteen essays contained therein represent the “very best in contemporary scholarship.” If so, this should be a matter of grave concern to people interested in the history of the American mystery genre before World War Two.

As the Companion is a skimpy book of less than 200 pages and it has fourteen essays, potential readers should be immediately clued in to the fact that the essays tend to be rather cursory. A listing of the essays further reveals that the book’s coverage is esoteric, leaving noticeable gaps:

Introduction (4 pages)

Early American Crime Writing (10 pages, excluding footnotes)

Poe and the Origins of Detective Fiction (8 pages)

Women Writers Before 1960 (12 pages)

The Hard-Boiled Novel (15 pages)

American Roman Noir (12 pages)

Teenage Detective and Teenage Delinquents (13 pages)

American Spy Fiction (9 pages)

The Police Procedural on Literature and on Television (13 pages)

Mafia Stories and the American Gangster (10 pages)

True Crime (12 pages)

Race and American Crime Fiction (12 pages)

Feminist Crime Fiction (14 pages)

Crime in Postmodernist Fiction (12 pages)

Further evidence of highly selective coverage can be found in the “American Crime Fiction Chronology” at the beginning of the book. Here are its milestones in crime fiction from 1841 to 1939:

1841 Edgar Allan Poe, “The Murders in the Rue Morgue”

1866 Metta Fuller Victor,

The Dead Letter

1878 Anna Katharine Green,

The Leavenworth Case

1908 Mary Roberts Rinehart,

The Circular Staircase

1923 Carroll John Daly, “Three Gun Terry”

1925 Earl Derr Biggers,

The House Without a Key

1927 S. S. Van Dine,

The Benson Murder Case

1927 Franklin Dixon,

The Tower Treasure

1929 Dashiell Hammett,

Red Harvest

1929 Mignon Eberhart,

The Patient in Room 18

1930 Carolyn Keene,

The Secret of the Old Clock

1934 James M. Cain,

The Postman Always Rings Twice

1934 Leslie Ford,

The Strangled Witness

1938 Mabel Seeley,

The Listening House

1939 Raymond Chandler,

The Big Sleep A pretty obvious pattern can be constructed from these fifteen fictional milestones:

The Distant Founder: Poe

The Women: Victor, Green, Rinehart, Eberhart, Ford, Seeley

The Hardboiled Men: Daly, Hammett, Cain, Chandler

The Non-hardboiled Men: Biggers, Van Dine

The Children’s Authors: “Dixon” and “Keene”

One would conclude from this list that American men donated practically nothing to the detective fiction genre after 1841 (Poe), outside of the hardboiled variant and juvenile mystery (the authors of the Hardy Boys tales). Apparently the only significant male producers in the nearly 100 years between Poe’s first story and Chandler’s first novel were the creators of Philo Vance and Charlie Chan.

But it gets even worse when we look at the actual text. S. S. Van Dine gets four mentions, all cursory, some problematic:

On page 1 his rules for writing detective fiction are mentioned, dismissively.

On page 29, he is dismissed as an imitator of Agatha Christie.

On page 43, he is called an imitator of Arthur Conan Doyle and used as the usual hardboiled punching bag for not writing about “reality” (though he interestingly is deemed “the era’s most popular writer”).

On page 136, it is claimed that The Benson Murder Case is “widely acknowledged as the first American clue-puzzle mystery”

Earl Derr Biggers gets one line, solely for having created an ethnic detective (see “Race and American Crime Fiction”).

At least these non-hardboiled make writers are mentioned! The hugely popular and admired genre author Rex Stout is another lucky lad. Though he missed the list of milestones, Stout nevertheless in mentioned in the text:

On page 47 he is noted for having merged hardboiled and classic styles.

On page 136, he is criticized, along with Van Dine, for ignoring race and gesturing “more toward Europe than actual American cities” and writing about rich white bankers, stockbrokers and attorneys (yup, “Race and American Crime Fiction” again).

On the other hand, if you are looking for anything on Melville Davisson Post, Arthur B. Reeve or Ellery Queen, forget it! They did not exist apparently; we only imagined them all these years.

Meanwhile, Anna Katharine Green gets two pages, Mary Roberts Rinehart three and Mignon Eberhart, Leslie Ford and Mabel Seeley together as a trio another two. (Heck, even the lovably loopy Carolyn Wells gets a line in this book.)

The editor of the Companion, Catherine Ross Nickerson (author of The Web of Iniquity — a book, you may not be surprised to learn, about Anna Katharine Green and Mary Roberts Rinehart — and, in the Companion, of “Women Writers Before 1960â€) lectures in her Introduction that:

“It is only fairly recently that the multiple genres of crime writing have been taken up as subjects of academic study; before that, they were entirely in the hands of connoisseurs and collectors, with their endless taxonomies, lists and value judgments. What Chandler opened up was a new way of looking at crime narratives, or rather looking through them, as lenses on the culture and history of the United States.”

This is an interesting idea indeed, but unfortunately Professor Nickerson’s own selective coverage gives us an inaccurate view of the genre and, thereby, surely, of American cultural history.

According to Nickerson, there were two indigenous creative strains in American mystery: the female domestic novel/female Gothic (the Brontes and Mary Elizabeth Braddon are admitted as influences here but not Wilkie Collins or Sheridan Le Fanu); and the hardboiled.

It seems that despite the existence of Poe, what we think of as the Golden Age detective novel was an artificially transplanted English import, about as American as scones and crumpets. Nickerson dismissively notes these “Golden Age” works for their “tightly woven puzzles and country houses full of amusing guests” and declares that they were “presided over by Agatha Christie and imitated by Americans like S. S. Van Dine.”

So if you were an American male writing mysteries that emphasized puzzles and had upper middle class/wealthy milieus, you were part of a British tradition and thus not worthy of inclusion in a historical survey of American mystery fiction. But if you were an American woman writing mysteries with puzzles and upper middle class/wealthy milieus, you were part of the American female domestic novel/Female Gothic tradition (even though some of this tradition is British and male) and you make it into the genre survey.

Make sense to you? It doesn’t to me. Personally I think Professor Nickerson should take another look at those “connoisseurs and collectors, with their endless taxonomies, lists and value judgments” who she dismisses so casually. There are still things that an academic scholar writing about the mystery genre can learn from them.

Granted, they often were men who tended to be overly dismissive of women’s mystery fiction — or at least the suspense strain in it that they mockingly termed “HIBK” (Had I But Known) — but writing important men out of the history of the genre is no way to redress the balance.

Crime literature may be about violence, but scholars of crime literature should not practice “an eye for an eye.” Doing so does not make for good scholarship.

Next Page »