March 2013

Monthly Archive

Sun 31 Mar 2013

A REVIEW BY DOUG GREENE:

GERALDINE BONNER – The Castlecourt Diamond Case. Funk & Wagnalls, hardcover, 1906. (“Published, December, 1905.â€) First appeared in Ainslee’s Magazine, November 1905. Currently available in several different Print On Demand editions. Online edition: https://archive.org/details/castlecourtdiamond00bonnrich

This is the second version of this review, In the first, employing suitable modesty, I credited myself with the discovery of Geraldine Bonner, an entertaining but (or so I thought) entirely forgotten writer. Having stated that Bonner is unknown, I then belatedly checked my facts … and I found that five years ago Kathi Maio praised another book by Bonner, The Black Eagle Mystery (1916), in Murderess Ink.

Such are the perils of research.

Ms. Maio says that Black Eagle is “a charming mystery” — a phrase that also describes Castlecourt Diamond. The story of the theft of the Marchioness of Castlecourt’s diamonds is told in six “statements.” The first, by the Marchioness’ maid, describes the theft, introduces the main characters, and mentions the two detectives, one official, one private.

The second section is narrated by “Lilly Bingham, known in England as Laura Brice, in the United States as Frances Latimer, to the police of both countries as Laura the Lady.” It’s not much of a surprise that Laura stole the diamonds, though whether she was acting for someone else is not yet clear.

On the whole, however, the mystery is primarily a vehicle for Bonner to produce a comedy of manners, and the interest in the second part is Laura’s successful attempt to plant the diamonds on an unsuspecting American couple, Cassius and Daisy Kennedy. The Kennedys have been courting London society (they already know “a bishop and two lords”) and thus can’t throw out Laura and her henchman when, pretending an invitation, they arrive for dinner.

Two parts of the story are statements by the Kennedys, detailing their schemes to rid themselves of the diamonds and culminating in the theft of the jewels by a seeming sneak-thief. John Burns Gilsey, a private detective engaged by Lord Castlecourt, narrates a section that explains his deductions pointing to the Marchioness as the instigator of the plot, but the book concludes with a statement by the Marchioness showing that Gilsey was only partly correct.

The Castlecourt Diamond Case is indeed charming, and it is made even more so by its brevity — with large type and margins it contains less than 30,000 words, a far cry from many Victorian and Edwardian detective novels, as anyone who has labored through, say, Lawrence Lynch’s novels with their 550 godawful pages will testify.

I can’t claim to be the discoverer of Geraldine Bonner, but I’m happy to join Kathi Maio in recommending her works.

— Reprinted from The Poisoned Pen, Vol. 6, No. 2, Winter 1984/85.

BIBLIOGRAPHY: [Taken from the Revised Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin]

GERALDINE BONNER (1870-1930). Born in Staten Island, N.Y.

The Castlecourt Diamond Case (n.) Funk 1906.

The Girl at Central (n.) Appleton 1915 [Molly Morganthau (Babbits)]

The Black Eagle Mystery (n.) Appleton 1916 [Molly Morganthau (Babbits).]

Miss Maitland, Private Secretary (n.) Appleton 1919 [Molly Morganthau (Babbits)]

The Leading Lady (n.) Bobbs 1926.

-Taken at the Flood (n.) Bobbs 1927.

Sat 30 Mar 2013

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[4] Comments

THE BACKWARD REVIEWER

William F. Deeck

HERBERT COREY – Crime at Cobb’s House. D. Appleton-Century, hardcover, 1934

For reasons best known to himself, the wealthy Charley Cobb hires Thomas Milne, lawyer and private detective. At Cobb’s estate in the horse country of Virginia a double murder takes place, perhaps in retaliation for an earlier unsolved double murder.

Tedium, at least for the reader, prevails here, and then it’s off to Washington, D.C., for additional boredom in a different setting.

A selection in Appleton-Century’s “Tired Business Man’s Library,” Corey’s novel is fitting. Soporific sums it up.

— From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 13, No. 1, Winter 1991.

Editorial Comment: This is the author’s only entry in Al Hubin’s Revised Crime Fiction IV.

Fri 29 Mar 2013

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[7] Comments

A REVIEW BY GLORIA MAXWELL:

H. R. F. KEATING – The Perfect Murder. Collins, UK, hardcover, 1964. Dutton, US, hardcover, 1965. Film: Merchant Ivory Productions, 1988 (Naseeruddin Shah as Inspector Ghote; Keating makes a cameo appearance about eight minutes into the movie). Softcover reprint: Academy Chicago, US, 1983.

This is the first in H. R. F. Keating’s series featuring Inspector Ghote of the Bombay Police Force. The Perfect Murder received the Mystery Writers of America’s Special Edgar Award and the Crime Writer’s Association’s Golden Dagger.

How interesting that The Perfect Murder refers to an attack on Mr. Perfect. But, will he survive, or succumb to his injuries? Inspector Ghote not only must try to solve this crime with little help from Lala Verde (Perfect’s employer — who talks annoyingly in rhymes) but must also try to solve a theft.

The mysterious disappearance of one rupee from the desk of a Very Important Person, the Minister of Police Affairs and the Arts, is equally crucial where Ghote’s boss is concerned. Struggling amidst bureaucratic red tape and incompetence, and a wife who is less than understanding about his working overtime, Ghote nevertheless forges ahead with both investigations.

A definitely different and amusing murder mystery.

— Reprinted from

The Poisoned Pen, Vol. 6, No. 2, Winter 1984/85.

Thu 28 Mar 2013

Three by JOHN WELCOME:

Reviews by George Kelley

JOHN WELCOME – Run for Cover. Faber, UK, hardcover, 1958. Knopf, US, hardcover, 1959. Harper Perennial, paperback reprint, 1983.

I have nothing but praise for the Perennial Library series: their selections are high quality fiction attractively packaged and priced. John Welcome’s Run for Cover is fun reading: light as cotton candy. Former intelligence agent Richard Graham is drawn into a tangled plot when the manuscript he is reviewing is stolen.

The haunting aspect: the manuscript was written by a man Graham knew was dead, Rupert Rawle. But the dead man has come alive and Graham is back on the trail of the man be once idolized, only to have Raw}e leave him for dead during a WWII commando mission. The writing is slick, cultured, and professional. The plotting is fast-paced, wild, and unpredictable. Perfect for vacation reading.

JOHN WELCOME – Stop at Nothing. Faber, UK, hardcover, 1959. Knopf, US, hardcover, 1960. Harper Perennial, paperback reprint, 1983.

Stop at Nothing is John Welcome’s best book. Simon Herald, former racing car star, faces 40 and a bitter divorce when he falls in love with a younger woman whose brother is hunted by vicious men in order to gain the secret of a formula that makes horses run faster.

Forget about the corny plot; Welcome fires away from page one and doesn’t let up on the action until a couple hundred pages later. Hairbreadth escape follows hairbreadth escape as Herald faces overwhelming odds, brutal beatings, a psychopathic killer, and an obsessed millionaire. What more could you ask for? This is seat-of-your-pants escapism at its best.

JOHN WELCOME – Go for Broke. Faber, UK, hardcover, 1972. Walker, US, hardcover, 1972. Harper Perennial, paperback reprint, 1983.

Go for Broke is one of John Welcome’s lesser works, but it still provides more excitement than most thrillers. Eric Vaughan, wealthy financier, accuses Richard Graham of.cheating at cards. Graham is mystified by the false charges, but finds himself drawn into a web of international intrigue where the seeds of treachery and double-cross in the past haunt the present.

Graham finds himself a social outcast, discharged from his part-time espionage position, and forced to sell his meager land holdings to pay for his legal defense. But he falls in love with a mysterious American woman and finds an unexpected clue to the frame he’s been put in.

The flaw in Go for Broke is the boring courtroom proceedings that take up too much of the book; once outside the stuffy legal chambers, the pages fly by. The conclusion will surprise no one, but it’s curiously satisfying.

— Reprinted from The Poisoned Pen, Vol. 6, No. 2, Winter 1984/85.

Editorial Note: A criminous bibliography for John Welcome can be found here on LibraryThing, along with a brief biography, which concludes: “He [John Needham Huggard Brennan] took up writing, under the pen name of John Welcome, to relieve the tedium of the country solicitor’s life.”

Wed 27 Mar 2013

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

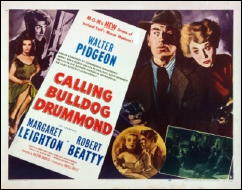

CALLING BULLDOG DRUMMOND. MGM, UK, 1951. Walter Pidgeon (Major Hugh ‘Bulldog’ Drummond), Margaret Leighton, Robert Beatty, David Tomlinson, Peggy Evans, Charles Victor. Based on a story by Gerard Fairlie. Director: Victor Saville.

Back in the late 60s, when I decided I wanted to live a life of adventure, I was quite taken with a gaudy Universal James-Bond-Rip-Off called Deadlier Than the Male, with Richard Johnson as Bulldog Drummond and Nigel Greene as bis arch-foe Peterson. Elke Sommer and Sylva Koscina were in it too, as scenery.

I liked the gaudy color, kinky violence, and general comic-book look of the thing. Don’t try to catch it on television, though, because it was castrated for Network Release and to my knowledge has never been restored. (Yeah, like someone would take the time to put all the sex and violence back in to this.)

Anyway, I tried the Drummond books and didn’t care much for the character in them at all, as he seemed something of a blow-hard bigot. Always liked the Drummond movies, though, including a B series from Paramount with John Howard, John Barrymore and lots of colorful baddies. And of course there was the great Colman film of ’29 which I viewed a wile back.

So I was sort of looking forward to Calling B. D. and was disappointed. The plot features a gang of crooks who operate in Military Style, prompting Scotland Yard to call Colonel Drummond out of retirement because of his military experience.

I don’t know about you, but I have a little trouble swallowing the notion that England in the 50s suffered from a shortage of men with Military experience, and the Surprise Bad Guy is unfortunately portrayed by an actor who later became mildly famous, so his off-screen voice tips us off immediately.

Add to this that Pidgeon seems to have taken his Dull Pills just prior to filming, and you have a very quiet movie indeed.

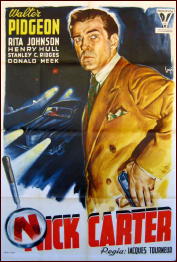

NICK CARTER, MASTER DETECTIVE. MGM, 1939. Walter Pidgeon (Nick Carter), Rita Johnson, Henry Hull, Stanley Ridges, Doctor Frankton, Donald Meek (Bartholomew), Milburn Stone. Director: Jacques Tourneur.

PHANTOM RAIDERS. MGM, 1940. Walter Pidgeon (Nick Carter), Donald Meek (Bartholomew), Joseph Schildkraut, Florence Rice, Nat Pendleton, John Carroll. Director: Jacques Tourneur.

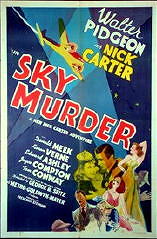

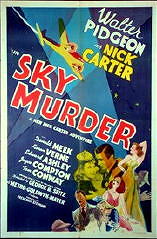

SKY MURDER. MGM, 1940. Walter Pidgeon (Nick Carter), Donald Meek (Bartholomew), Kaaren Verne, Edward Ashley, Joyce Compton, Tom Conway. Director: George B. Seitz.

Pidgeon came off much better in a series of “B’s” from MGM in the late ’30s centered around a character called Nick Carter, though for all the care they took to recreate the old Dime Novels, they might as well have called him The Saint or Bulldog Drumond or V.I. Warshawski. Nick Carter Master Detective, Phantom Raiders and Sky Murder are all quite fun and you should see them if you ever get a chance.

With that sonorous voice of his, Pidgeon always sounded like Gregory Peck’s older brother, but these films play against his tendency to stodginess and come out very light and fluffy. The first two were stylishly directed by Jacques Tourneur, but the best thing in them is the Comedy Relief played by Donald Meek.

The comical sidekick was as much a fixture of the B-Mystery series as he was in the B western, but Meek and the writers here lift the concept to dizzying heights. His Bartholomew is not the standard dim-witted clod of most B-Mysteries: he’s a dangerous madman, given to melodramatic fantasies and theatrical outbursts of classic,dimensions.

He looks like the kind of guy who might bite you on the leg for no good reason at all, and given the chance to play something besides a timid fuddy-duddy, Meek indulges himself with a flair for wild-eyed comedy I’d never suspected in him. He is that rarity, a Comic Relief you actually look forward to seeing, and be adds immeasurably to the films. Catch these if you can.

Editorial Comment: Mike Grost has some interesting things to say about the two Nick Carter films directed by Jacques Tourneur. Check out his website here.

Tue 26 Mar 2013

REVIEWED BY MICHAEL SHONK:

THE BROTHERS BRANNAGAN. Syndicated; 1960-1961. 39 episodes @ 30m each. A Brad-Jacey Production in association with CBS Films. Cast: Steve Dunne as Mike Brannagan and Mark Roberts as Bob Brannagan. Recurring Cast: Barney Phillips as Lt. Avery. Created by Wilbur Stark and Jerry Layton. Theme by Alexander Courage; filmed on location in Phoenix Arizona.

Neither Steve Dunne nor Mark Roberts had the acting talent to impress Stanislavski, but they were likable as the leads, as were their characters. Bob and Mike Brannagan were brothers and best friends. Both, like real PIs as opposed to the fictional ones, worked within the law. In “Wheel of Fortune†they refused to break into a place for the client because it was against the law, and as they told the client, they were PIs not burglars.

Bob was the practical one. He handled the money and was most likely to solve the case through deduction. He enjoyed his time with women, but he was not the womanizer his brother Mike was.

There was a harmless quality to Mike’s pursuit of women, even when he pulled out his little black book filled with pick-up lines. Mike lent a more creative side to the solving of the mystery.

Despite the low budget, lack of time and other limitations that came with TV-Film syndication, the writing and direction were the series strength. The thirty-minute story lacked time for much character or mystery depth, but the stories fast pace still had time for fist fights, shootouts, chases, light humor and nice (if today predictable) twists.

Few of the writers, directors and actors may be remembered today but they knew how to produce television shows that were enjoyable to watch. Writers such as Harold Jack Bloom (HEC RAMSEY) kept the stories interesting and entertaining. Directors such as Eddie Davis (BOSTON BLACKIE) may have shot fast but still had time to frame shots with near perfect use of film composition to add visual depth to the action and story.

The series made good use of the soundtrack. With much of the action happening inside the home base for the brothers, the dining room of the Mountain Shadows Resort (a real place), the background music often featured a piano playing jazz. Alexander Courage (STAR TREK) composed the opening theme music.

The series chief gimmick was the episode’s opening where, as the theme played, we would watch the Brannagans walk away from the camera, their backs to us, until they hear a voice shouting “Hey Brannagan.†They would turn and Bob would ask “Which one?†The picture would cut to someone who usually needed help. The brothers would walk back directly at the camera.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ceJpT0jxfdA

EPISODE INDEX: There was no on screen credit featuring episode title. Titles and episode number used here come from IMDb.com. The same IMDb.com that has Bob Brannagan listed as Bill in many of its episodes credits.

“A Very Special Woman.†Episode 1. Written by Harold Jack Bloom Directed by Paul Landres. Produced by Wilbur Stark and Jerry Layton. GUEST CAST: Dorothy Green, Leo Gordon, and Keith Richards. *** The local fence learns the hard way never dump the femme fatale, not when there are other men around.

OPENING- HEY BRANNAGAN! : A beautiful woman with a broken high heel shoe needs help.

“Wheel of Fortune.†Episode 24. Teleplay by John Dana. Story by Malcolm Stuart Boylan. Directed by Eddie Davis. Produced by Wilbur Stark and Jerry Layton. GUEST CAST: Lynn Cartwright, Ed Hashim and K.T. Stevens. *** A rich short-tempered Mexican with his wife arrives in Phoenix claiming a local art dealer has stolen a family treasure. The art dealer claims she does not have it and wants the money he cheated her out of in an art deal.

OPENING- HEY BRANNAGAN! : A sign saying “Support Your Community Chest $1 a Chance with a kiss†and a beautiful woman asking them if they care to try their luck.

“Mistaken Identity.†Episode 28. Teleplay by Sam Ross, from a Story by William Link and Richard Levinson. Directed by Anton Leader. Produced by William Stark and Jerry Layton. GUEST CAST: Joann Manley, Lewis Charles and Bailey Harper. *** The boys are entertaining a pretty vacationing teacher when she is kidnapped.

OPENING- HEY BRANNAGAN! : Two pretty girls waving at the brothers. Mike notes there’s one for each of them.

“Terror In the Afternoon.†Episode 30. Written by Al C. Ward. Directed by Jean Yarbrough. Produced by Wilbur Stark. GUEST CAST: James Flavin, Robert Harland, and Gloria Talbott. *** After two construction accidents costs the lives of a woman’s brother then fiance, she hires the brothers to check out the dam. The twist has her rich overprotective father building the dam and her wanting to see it destroyed.

OPENING HEY BRANNAGAN! : A dog is trapped in a lake.

From “Broadcasting†(8/29/60): “Producer Wilbur Stark has announced a new policy in giving film editors on his tv (sic) series credit as ‘creative film editor’ plus part ownership of the properties. First to receive this benefit is John Woodcock, editor of THE BROTHERS BRANNAGAN, which makes its debut this fall in syndication for CBS TV-Films. Mr. Stark said he hopes the move will lure the best film editors to his company. He said film editors are perhaps even more important than directors.â€

Blasphemy! While the director is not the major power in series TV as he or she is in theatrical films, Hollywood would never claim the film editor was more important (even if they can be) than a director. In the four episodes above, “Terror in Afternoon†was the only one where John M. Woodcock had the on screen credit of Creative Film Editor. Oddly enough it was the only one of four with Wilbur Stark getting sole producing credit. In the other three episodes John M. Woodcock received the on screen credit of Editorial Supervisor.

There are a dozen episodes available in the collector’s market including two websites, Thomas Film Classics, Robert’s Hard To Find Videos, and the other usual suspects.

SUGGESTED READING…

James Reasoner:

http://jamesreasoner.blogspot.com/2011/07/tuesdays-overlooked-tv-brothers.html

The Rap Sheet:

http://therapsheet.blogspot.com/2012/10/oh-brothers-where-art-thou.html

Thrilling Detective: (We will forgive the hard working nearly perfect Kevin Burton Smith for his misspelling the brothers’ name. I know my auto-correct agreed with him.)

https://www.thrillingdetective.com/brannigan.html

Sat 23 Mar 2013

THE BACKWARD REVIEWER

William F. Deeck

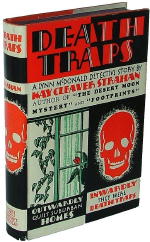

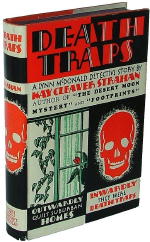

KAY CLEAVER STRAHAN – Death Traps. Doubleday Crime Club, hardcover, 1930. Reprint hardcover: Grosset & Dunlap, no date (shown).

There are several mysteries about the shooting of Gilbert Dexter in San Francisco. Would his brother, Bob, have shot him? Would Bob have managed only to wound him at point-blank range? Were the French windows open or locked? Why were there two revolvers in the room? Further and deeper puzzlement develops when the next-door neighbors are found dead in their locked room with no sign of foul play and no explanation of their deaths.

Since the head of the Dexter family is a retired judge, the authorities investigate the shooting in a gingerly manner, and, so it would seem, there is not much involvement by the police in the locked-room case. Fortunately, Bezaleel Lucky, millionaire former grocer and husband of one of Judge Dexter’s daughters, takes it upon himself to investigate in amusing fashion with his proverbs, his constant interruptions, and his complaint that all anyone, but not him, wants to do is talk.

Sometime I will have to take another look at Strahan’s Footpnnts, which I vaguely remember as being one of those dreary psychological novels in which turning pages is a chore. Maybe I missed something.

— From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 13, No. 1, Winter 1991.

Editorial Comment: According to Hubin’s Crime Fiction IV, the detective of record in Death Traps, as he was in all seven of Kay Cleaver Strahan’s mysteries, was a fellow named Lynn MacDonald, whom Bill Deeck did not mention. If anyone reading this is familiar with the book, where does MacDonald fit in, and what kind of name is Bezaleel Lucky?

The Lynn MacDonald series —

The Desert Moon Mystery (n.) Doubleday 1928.

Footprints (n.) Doubleday 1929.

Death Traps (n.) Doubleday 1930.

The Meriwether Mystery (n.) Doubleday 1932.

October House (n.) Doubleday 1932.

The Hobgoblin Murder (n.) Bobbs 1934.

The Desert Lake Mystery (n.) Bobbs 1936.

Fri 22 Mar 2013

THREE CRIME NOVELS BY C. M. KORNBLUTH

by Josef Hoffmann

C. (Cyril) M. Kornbluth (1923–1958) is a well-known science fiction author. What is less well known, however, is that he was also a successful crime writer. In the second half of the 1940s he wrote detective stories for pulp magazines. Later, he published crime novels under the pseudonyms Jordan Park and Simon Eisner. According to Hubin’s bibliography, these were:

— Simon Eisner: The Naked Storm, Lion Books #109, 1952; cover art: Robert Skemp.

— Jordan Park: Sorority House, Lion Library LL97, 1956 (together with Frederik Pohl); cover art: Clark Hulings.

— Jordan Park: The Man of Cold Rages, Pyramid Books G368, 1958; cover art: Harry Schaare.

A further novel, written jointly by Pohl and Kornbluth, can be found in Hubin: Gladiator-at-Law (Ballantine, 1955). In addition, there were Kornbluth’s novels Takeoff (Doubleday, 1952) and The Syndic (Doubleday, 1953). These novels have elements of a criminal plot, but because the action is set in the future and these novels are generally considered to be science fiction, I omit them here.

Kornbluth’s earliest crime stories include the two detective stories in Black Mask: “Beer-Bottle Polka†(September 1946; Vol 29 #1; pp 35-43) and “The Brooklyn Eyeâ€, 29, No. 2 (Nov 1946; Vol 29 #2; pp 79-94). The hero and narrator in each case is Tim Skeat, a private detective in New York City. Some action elements from earlier Pulp stories are reused in the crime novels.

The Naked Storm tells of a train journey through a snowstorm from Chicago to San Francisco. The locomotive eventually gets stuck in the snow on a pass in the Rocky Mountains, and the people on the train are cut off from civilization for three days. Using numerous observations and experiences, the novel describes how individual persons prepare for the train journey while the snowstorm is approaching, as well as the journey itself and the catastrophe.

The novel has no underlying continuous narrative thread, but is instead constructed from larger and smaller illustrations of impressions and actions on the part of the persons involved. The combined narrative particles generate an overall impression that constantly changes, like the pictures in a kaleidoscope. While the reader is at first somewhat clueless, due to the diversity of the impressions and experiences, events intensify during the train journey around four persons:

— Hal Foreman, a news agency boss; he is being coerced by a gangster syndicate into establishing a news agency in San Francisco.

— Mona Greer, a lesbian bestselling author, who uses her glamorous status to seduce inexperienced young women, who she then proceeds to discard, once she has enjoyed her sexual conquest.

— Joan Lundberg, a pretty young woman, who is traveling to a political conference in San Francisco.

— Boyce, a businessman in the floor coverings industry, who is unhappily married.

Both Boyce and Greer have their eye on Joan Lundberg. Foreman supports Boyce, as he hates lesbians like Mona Greer.

The novel describes how environmental conditions influence people’s behavior, in particular how they compulsively abandon their moral standards in the face of snow and freezing ice. The bar is plundered, drugs are stolen from the doctor’s bag, insults and fistfights abound. And Foreman decides to murder Greer.

The novel is more of a mainstream novel than a crime novel. Some of Kornbluth’s own experiences are worked into the depiction of Hal Foreman. This makes it all the more dubious that the reader is expected, through the manner in which the novel is written and concludes, to identify with Foreman’s prejudice against and hatred of homosexuality. This diminishes the quality of the novel considerably.

Sorority House is to an even greater extent more of a mainstream novel than a crime novel. Life in the Eleusis Academy for Women, a college in a small provincial town in Pennsylvania, is presented in a socially critical manner. The head of the college is Dr. Mildred Matthewson, an old maid and historian, who tyrannizes and spies on both students and teaching staff. She is malicious, extortionate and scheming.

Four female students and three teachers form the centre of events. The four young women are accepted into to the sorority of the Lambs and enjoy the privilege of living in their house. They are Ann Riker, an aspiring writer, who is keen to suppress her lesbian inclinations, Kathryn Jackson, a stipendiary from the lower classes, who wishes to become a Latin teacher, Joy Squires, a beauty who embarks on a relationship with a young lecturer, and Clara Gwynn, a rather chubby student who develops a talent for mathematics. The three lecturers are the young English teacher Jim Henschel, the journalism teacher James McGivern, a drinker, and the new, unapproachable mathematics teacher Dr. Crouch.

The entanglements that befall the students and lecturers are told in an exciting manner. But the action only takes a turn towards becoming a crime novel from page 166. During a dance party, arranged elaborately by the Lambs, Dr. Matthewson is found dead in the night, away from events, in the Mall. The police investigation, which commences immediately, establishes that the death was violent: it is murder. As the head of the college was not short of enemies, there are numerous suspects. Some detection and dramatic action takes place on the last 25 pages. The solution is no surprise.

From our current perspective the prejudices against lesbian love and against women who aspire to social mobility by means of an academic education are reactionary. These prejudices become apparent above all at the end of the novel, which is not revealed. There is also an alarming empathy for a kind of self-justice. Finally, the different blurbs on both Lion Books falsify the content of the narrative by means of exaggeration, which I find annoying, and which does not do justice to the authors.

The hero of the third novel, The Man of Cold Rages, is Leslie Greene. His wife Peg and son Val are run over and killed by a car in Chicago. The car is driven by contract killers who shot Dr. Emilio Hernandez, who was sitting on a bench, and then killed the two likely witnesses to the crime, Peg and Val, with their car. Hernandez had been granted political exile. He came from the (fictional) Republic of La Paz, a small South American country ruled by the fascist dictator General Serrano. Hernandez was obviously murdered because of his oppositional political activities.

Life no longer has any meaning for Leslie Greene. The only thing that still interests him is the punishment of the murderers. However, the police investigation is unsuccessful. Greene decides to travel to La Paz in order to kill the person who ordered the murders, General Serrano. For an indeterminate period he moves into a hotel in the republic’s capital city, which is decorated by countless portraits and statues of the dictator.

Because Greene is an artist who can paint excellent portraits, he tries to attract attention by painting the portrait of the hotelier’s cousin, Senorita Isabel Rocas. He achieves this quite quickly, leading to the intended invitation to see General Serrano. It is arranged that he will paint a portrait of the dictator, who will model for the painting regularly.

At the same time, Greene makes contact with the opposition, which operates underground. The opposition is planning a non-violent upheaval and a general strike. Greene’s plan to murder the dictator is rejected by the members of the opposition. But Greene sticks to his decision. Events take their course and are complicated further by the fact that Isabel falls in love with Greene.

The Man of Cold Rages is a mixture of political thriller and suspense novel and resembles at times the novels of Eric Ambler. The typical Ambler protagonist lands in terrible danger and political adventure, without knowing what is happening to him; in contrast, Kornbluth’s hero seeks out the challenge cold-bloodedly.

This novel is not for readers who prefer their books to be as realistic as possible. For example, it is very unlikely that a visitor to a severely guarded dictatorship can transport a loaded pistol in his luggage on an airplane without any prior precautions, so that the weapon is only discovered by an overly enthusiastic chambermaid in the hotel. Otherwise the thriller is well written, with a number of very impressive scenes. It is exciting to read, albeit not without a certain amount of clichés.

While Kornbluth’s first Black Mask story is roughly hewn and bursting with violence and cruelty, he refined his narrative technique in the crime novels, using violent scenes in a more differentiated manner. Kornbluth sometimes found himself to be cruel. This was contradicted by acquaintances, who considered his behavior to be friendly.

The truth is that he was cruel in his fantasy world, as demonstrated in his first Black Mask story and – in diluted form – still in his first thriller. However, his literary attitude towards violence and self-justice obviously changed over the years, as can be seen in his final crime novel.

It is a pity that the author died so young; we have been deprived of some probably very entertaining thrillers as a result. To those who wish to learn more about Kornbluth I recommend the detailed biography by Mark Rich: C. M. Kornbluth: The Life and Works of a Science Fiction Visionary.

— Translated by Carolyn Kelly.

Wed 20 Mar 2013

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

VICTOR CANNING – The House of the Seven Flies. Hodder & Stoughton, UK, hardcover, 1952. Mill-Morrow, US, hardcover, 1952. Berkley #F730, US, paperback reprint, 1963.

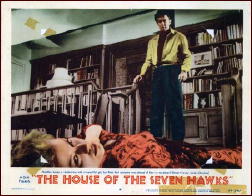

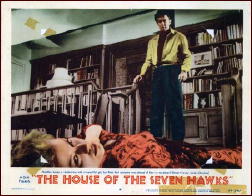

THE HOUSE OF THE SEVEN HAWKS. MGM, UK, 1959. Robert Taylor, Nicole Maurey, Linda Christian, Donald Wolfit, David Kossoff, Eric Pohlmann. Screenwriter: Jo Eisinger, based on the novel The House of the Seven Flies, by Victor Canning. Director: Richard Thorpe.

Victor Canning’s THE HOUSE OF THE SEVEN FLIES (Morrow, 1952) has intrigued me for various and sundry reasons since I came across it in my late teens, but I should tell you for starters, it’s pretty much a generic adventure/crime novel of its time, with little to distinguish it from a dozen others.

The story opens in 1944 with some Nazi big-wig looting valuable jewels from a Dutch bank—or trying to; the boat he’s leaving in gets sunk in the canals near a city called Veere and the treasure is lost forever.

Yeah (as they say) right.

The story picks up again in 1952 with Roger Furse, an American ex-serviceman now operating a charter boat in the North of England. Like any hero in this sort of thing, Roger’s a straightforward guy, but he’s not above bending the law a bit, so when a Dutchman who chartered the boat for a bit of coastal mucking about offers him extra to take him across the North Sea to the Dutch town of Veere, Roger doesn’t need much persuading. But when the Dutchman dies (mysteriously, but apparently of natural causes) Roger decides he should make sure he’s not carrying anything incriminating, goes through the man’s baggage and finds (you guessed it) a map to the “lost†treasure.

Whereupon Canning rounds up the usual complications: a cute-perky-bouncy young lady who was working with the Dutchman to recover the loot; a lugubrious police detective who tells Furse that his passenger was murdered before he ever got on board, victim of a slow poison; a showy crook with an entourage of nasty thugs, and a lovely femme fatale-type who may have killed the Dutchman.

Having assembled his cast, Canning puts them through the usual paces: Furse and the cute girl fall in love; the Dutch cop plods patiently; the showy crook offers bribes and threats; his hired nasties get tough, and the femme tries seduction. We get a couple of chases (well-handled, I must admit) a couple fights (likewise) and some sea-going stuff that Canning handles particularly well, all capped by the usual ending.

Okay so the first thing that intrigues me about this book is the title; who-the-hell would call a book THE HOUSE OF THE SEVEN FLIES? Who would publish anything with a title that connotes dull classics and household pests? Who did they think was going to buy anything labeled THE HOUSE OF THE SEVEN FLIES? I mean I wrote a book a couple years ago called EASY DEATH, and I have an eight-page list of publishers and agents who won’t even look at it, so how does Canning put out a book with a title like that?

Well in point of fact, Morrow published it and it was bought by no less than MGM, who packaged it as a medium-budget flick for their declining star Robert Taylor in 1959, adapted by Jo Eisinger and directed by that reliable workhorse Richard Thorpe. Just a few years earlier, Thorpe and Taylor had worked together on big-budget extravaganzas like IVANHOE and KNIGHTS OF THE ROUND TABLE, but here they were clearly just treading water.

For most of its length, THE HOUSE OF THE SEVEN HAWKS (as they wisely re-titled it) is as undistinguished a movie as the book was a book. Except for Taylor, there are no big stars or even any memorable character actors. The chase scenes and sea-going stuff are jettisoned for reasons of economy, and the stunt work in the fights could be charitably described as duller than ditchwater. Yet HAWKS stayed in my memory for years, and I don’t know whether to blame Director Thorpe or Writer Eisinger — or to praise them.

The thing is this: about 20 minutes in, HAWKS segues into a fugue from THE MALTESE FALCON; Taylor (now named John Nordley for some reason!) is approached by an effeminate little perfumed man with a cane who works for a fat, loquacious boss associated with a lying femme fatale. Big chunks of dialogue are ripped from FALCON, with the fat man AND Taylor bluffing about what they need to find out, and later Taylor tells the femme what a good actress she is … then they kiss and he sees the fat man’s henchman outside the window, just as in FALCON.

Like I say, I don’t know who was responsible for this wholesale rip-off/homage, but it’s worth remembering that Thorpe once re-shot the 1937 PRISONER OF ZENDA scene for scene. Whatever the case, when I saw this on Network TV back in the late 60s, before videotapes, DVD or even Turner Classic Movies, the blast from a classic seemed delightfully amusing.

Or at least it made the film a little less forgettable.

Tue 19 Mar 2013

A TV Review by MIKE TOONEY:

“All the Time in the World.” An episode of Tales of Tomorrow (ABC-TV, 1951-1953). Season 1, Episode 37 (37th of 85). First broadcast: 13 June 1952. Cast: Esther Ralston (The Collector), Don Hanmer (Henry Judson), Jack Warden (Steve), Lewis Charles (Tony), Sam Locante (Bartender), Bob Williams (Narrator). Writer: Arthur C. Clarke (story, 1951). Director: Don Medford.

“No criminal in the history of the world had ever possessed such power. It was intoxicating…” — From the original short story.

In his stuffy office Henry Judson does no apparent work — which is understandable, since Henry is a mid-level criminal sometimes referred to as a fixer. Like middle management in legitimate business, Henry arranges for things to be done, usually without much personal involvement on his part. Whenever he sees an opportunity for criminal “enterprise,” he fixes things with still lower-level thugs who then do the dirty work.

But on this hot afternoon, he gets very personally involved with a strange but beautiful woman who is willing to give him a hundred thousand dollars to do a job, with another hundred thousand when he completes it.

The job? She gives him a laundry list of things to steal, which includes not only rare books but also some of the most valuable paintings in the world. Just walk in, pick them up, and walk right out. Piece of cake.

Henry’s skepticism is understandable, of course — until the woman, who insists on being called “The Collector,” shows him how it’s done.

When Henry woke up that morning he never remotely suspected that before the day was through he would be using a bracelet to break into a museum and — even more importantly — agonizing over how to spend the last few precious moments of his life.

Along the way, this story quietly raises a question: Can it be regarded as a crime if someone steals something in order to save it?

Retrovision has “All the Time in the World” archived here.

Arthur Clarke’s original story is online here. In his book, The Collected Stories of Arthur C. Clarke, he writes: “This was my first story ever to be adapted for TV — ABC, 13 June 1952. Although I worked on the script, I have absolutely no recollection of the programme, and can’t imagine how it was produced in pre-video-tape days!”

——————————————————————————————————–

IMDb: http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0717017/

Next Page »