October 2014

Monthly Archive

Thu 30 Oct 2014

Reviewed by DAVID VINEYARD:

THE UNINVITED. Paramount Pictures, 1944. Ray Milland, Gail Russell (debut), Ruth Hussey, Donald Crisp, Alan Napier, Corneila Otis Skinner, Dorothy Stickney, Barbara Everest. Screenplay by Dodie Smith and Frank Partos, based on the novel Uneasy Freehold by Dorothy Macardle. Music: Victor Young (“Stella by Starlight”). Cinematography Charles Lang. Directed by Lewis Allen.

First a a huge SPOILER WARNING in flashing red lights if you don’t know the film or the novel. Things are given away here you should see the first time in the film or read in the book.

The Uninvited is a whodunnit — at least a whohauntedit, a murder mystery.

Well, partially.

The Uninvited is a romantic comedy.

Parts of the beginning certainly and there are light touches throughout.

The Uninvited is a psychological thriller.

Getting closer.

The Uninvited is a modern gothic.

Almost there.

The Uninvited is a ghost story.

No, that’s an understatement, The Uninvited is the film ghost story.

Robert Osborne, hosting an episode of the Essentials on TCM with Drew Barrymore that featured Robert Wise’s The Haunting, put it best. The Uninvited is the best ghost story ever filmed. It was then, it is now. All the special effects, all the pyrotechnics, all the leap out of your seat and scream movies made before or since pale beside this simple little tale of love, jealousy, and murder beyond the grave — with a human assist.

Because The Uninvited has something no other ghost story has, something as uncomplicated as this: The Uninvited has absolute unshakable conviction. These are ghosts you will not laugh at. Whatever your beliefs, however rational you are, this movie will do its damnedest to at least convince you for its short running time that Stella Meredith (Gail Russell) is under siege by a spirit beyond the grave eager to take her life in an act of other worldly revenge. And for most people, viewers and critics alike, it succeeds — it more than succeeds.

Is it Stella’s goddess-like mother, Mary Meredith, or the foreign model, and her father’s mistress, Carmel comforting Stella, threatening Stella? Which spirit weeps for Stella Meredith, and which wants to drive her to suicide? You will care if you watch this one.

And you will consider sleeping that night with the lights on.

I suppose this film won’t mean much to the gore and goo fans, there is nothing in it to make you throw up or gag, but its scares are deep and real, the frisson they induce a deep soul chilling hair on the back of the neck crawling kind of fright that for me has only been approached a handful of times on screen — the final moments of Hitchcock’s Psycho, the ending of John Farrow’s Night Has a Thousand Eyes, Robert Wise’s The Haunting, The Innocents, Val Lewton’s best, and too few others; it is the genuine fright and nerve chilling presence of supernatural evil the inexplicable, the hidden, the uninvited. It’s a stunning debut for both Gail Russell and director Lewis Allen.

It is the best ghost story ever filmed, and that opinion is shared with no few critics. Critics who don’t like anything anyone else praises love this film because it is so unpretentiously and perfectly exactly what it wants to be — a chilly tale of ghosts to follow by a warm fireplace with the lights left on.

I saw this for the first time at age ten (the same age I saw Ghost Breakers, a good year) on the late movie on a Friday night with my mother after a stormy night had passed and neither of us could sleep. When my father got home the next day he wanted to know why we were sleeping so late and every light in the house was turned on.

Rick (Ray Milland, Roderick in the book) wants to write music, and with his sister, Pam (Ruth Hussey), and their dog Bobby, he spies an old cliff side house on the rocky moody Devon coast. They could never afford it of course, but it turns out the Commander (Donald Crisp) wants rid of it at a price they can just hope to pay. He’s unfriendly and downright hateful, and apparently a snob as well, for he wants his grand-daughter Stella — a moody fey girl who lies to Milland and Hussey to keep them from buying the house — to have nothing to do with the new tenants — and to stay away from the house at all costs. He is selling it in hopes of keeping her away.

You know that won’t work. Ray Milland is going to London to arrange the move while Hussey stays behind, and feeling pity for Stella, whom he took an instant dislike to, he tries to cheer her up falling in love with her as he does. He, at least, is haunted by Stella Meredith, no matter who haunts Stella.

Milland comes back with their housekeeper Lizzie (Barbara Everest), her cat in tow, and there is something Pam has learned she has to tell him.

The house is haunted. And that night he hears the weeping of the ghost.

Milland: “Does it come every night?.â€

Hussey: “No, just when you start to think you dreamed it, it comes again.â€

A haunted house, what a lark, but not to Hussey There is something. Maybe that’s why the housekeeper’s cat is freaked out. Maybe that’s why their loyal dog runs away, maybe that’s why the housekeeper won’t stay in the house overnight and frets over the two young people she virtually raised living in such an evil place.

Or maybe it’s that beautiful room with the north light, Stella’s artist father’s studio, now Milland’s music room, maybe it’s because it gets so cold sometimes, or the way it depresses people and seems to drain them. Neither Milland or Hussey notice the first time they sit in the room that they suddenly become depressed, or the flowers that wilt while they aren’t looking.

And then it might be the weeping woman who keeps them up all night. Maybe it’s just a depressing old place and that’s why Milland can’t quite finish his opus, “Stella by Starlight,” written for Stella Meredith, but suddenly so sad and so haunting when that wasn’t what he meant at all. Maybe it’s just them.

Not in this movie. Unlike Robert Wise’s The Haunting, these people aren’t haunting themselves. What walks in this house does not walk alone. There is never the least hesitation about it: ghosts are real, and not merely psychological interpretations of impressionable minds.

Then there’s that cheap scent, lovely, but nothing the elegant and perfect Mary Meredith would have worn, mimosa …

Old houses, they have drafts, funny noises, there are cliffs and they are on the sea, winds blow, there are caves, there are stories …

Commander: “Stella will never enter that house!â€

Milland: “Great Scott, you believe it’s really haunted!â€

And there is Stella, drawn to the old house by forces and needs she can’t explain, but somehow so vulnerable in that old place as if the house itself was both a warm loving mother inviting her and a cold murderous bitch trying to destroy her.

After they have to send for the local doctor, Alan Napier, when Stella is overcome after running blindly toward the cliff where the old dead tree stands, where her parents both died, they learn Bobby is now living with him, and find a new ally in solving the mystery of the house and Stella Meredith.

There was a scandal, the doctor explains; Meredith had a model, a fiery foreign type named Carmel, a Spanish gypsy. Carmel died a week after Mary Meredith was killed while trying to prevent her husband’s suicide on the cliff. Meredith was a scoundrel it seems and poor Stella has art in the blood, something she seems relieved about compared to the perfect Mary Meredith.

Stella: “Between you and me and the grand piano father was a bit of a bad hat.â€

When Stella is better, and against her grand-father’s wishes, they invite her back for a seance. Milland and Napier plan to control the seance and convince Stella there is no spirit. Not as good an idea in practice as it may have sounded in theory. Again they sense the strange scent of mimosa, again Stella feels nurtured and warmed — and again something attacks.

Whatever, it is clear now, the house is haunted — by two ghosts, one Stella’s loving mother, the other a vengeful spirit who is a real threat to her.

But when the Commander discovers what they have been up to he decides to send Stella away to a home run by her mother’s closest friend and companion, a formidable and cold woman who worships the ground Mary Meredith’s angelic feet hardly touched, Miss Holloway (Cornelia Otis Skinner who ironically Gail Russell played in the film version of her book Their Hearts Were Young and Gay and its sequel) who created the Mary Meredith Home for Women.

She worships Mary Meredith a bit too much perhaps because there is a hint of lesbianism you could drive a semi through, never exactly said. They hint the hell out of it though. Big fairly explicit lead booted hints, yet maintaining the perfect balance that is the reason this film is great.

Miss Holloway: “… her skin was perfect, and her bright bright hair, she was lovely …†Anyone who doesn’t figure out this relationship is painfully naive.

Just by coincidence the trained nurse caring for Mary Meredith and Stella the night of the tragedy was a certain Miss Holloway.

Stella hates and fears her.

Milland and Hussey visit Miss Holloway and hear her version of the story. Carmel tried to kill Stella, Mary Meredith saved her but fell to her death. Meredith killed himself.

And then in the strangest of coincidences, the wind just happens to blow open the journals of the old doctor Napier replaced to the notes on Mary Meredith and Carmel, a quite different tale than the one they have been led to believe. Mary Meredith was a cold murderous bitch, who the old doctor suspected murdered Carmel by leaving windows open so the pregnant woman caught pneumonia — while she was pregnant with Meredith’s child, Stella.

Mary Meredith wasn’t murdered by her husband. They fell to their death while he struggled with her to keep her from throwing herself and Stella off the cliff in a fit of vindictive and murderous jealousy. Mary Meredith is a monster of epic proportions. Miss Holloway murdered Carmal as far as the old doctor was concerned.

Don’t screen this one on Mother’s Day.

This is the secret the Commander has held all these years. The secret Miss Holloway would kill to protect, the secret of the old house, Mary Meredith’s secret. Stella isn’t really his grand-daughter, and the goddess Mary Meredith was a murderous harridan, but the old man truly loves Stella, he gives his life trying to save her.

Mary Meredith wants to finish what she started.

Compel Stella to throw herself from the exact spot where she fell, she has already tried once, the cliff by the dead tree.

Revenge from beyond the grave.

Murder from beyond the grave.

And only Carmel, her real mother, stands between them, and Mary defeated her once already; all she can do is comfort and try to warn her child.

Not really enough standing against Mary Meredith.

Thank God Stella is with that monster Miss Holloway. But she’s not. Skinner has gone mad as a hatter and sent Stella home, home to the embrace of Mary Meredith. Mary wants her, and Mary shall have her. And when Stella finds the Commander dying of a stroke at the house, by the sea he tries to tell her, warn her, but too late. Mary Meredith has the hated child within her grasp alone at last, and Stella flees her, running in blind fear towards the very place Mary and Meredith fell to their death.

Stella: I’m not afraid of anything here.

Commander: “Then be afraid, be very afraid!â€

Skinner gives a finely tuned performance with an impressive scene of madness. No wonder she was one of the great ladies of the stage and American theater.

Milland, Hussey, and Napier have gone to take Stella from Miss Holloway. They are rushing back, but can they reach Stella in time?

The final confrontation with the hated Mary Meredith remains the single best scene of its type ever filmed. Milland, alone on a darkened stairway confronting a murderous spectral form with nothing but a candle for protection, is an image you won’t forget and the final reckoning with Mary Meredith the perfect ending. But don’t be too surprised if your courage cracks a little the way Milland’s voice does. Mary Meredith is something else.

And, by a narrow squeak, it’s a happy ending. But as Wellington said of Waterloo, a near run thing. As a shaken Milland points out, he might have had Mary Meredith as a mother-in-law. Stella’s relieved too, she’d much rather be the illegitimate daughter of Meredith and his mistress, Carmel, than have Mary Meredith’s cold blood running in her veins. Spanish gypsy beats the cold murderous Mary Meredith by a mile.

I can’t say as I blame her.

The title has multiple meanings. Milland and Hussey are uninvited intruders; Stella is uninvited at the house and uninvited into the world; Carmel, the Spanish mistress ,was uninvited,; the Commander is uninvited to the seance and at the end to the house, his death uninvited at that moment; he is clearly uninviting to Milland and Hussey; Milland’s attentions to Stella are uninvited, even their dog shows up uninvited at one point and chases a squirrel who is himself uninvited; the doctor treats Stella and investigates uninvited; Bobby showed up on his doorstep univited; death was uninvited; the spirits dwelling there are uninvited. About the only people actually invited in this film are the viewers.

If at any moment in this film there had been a single misstep, a single false moment, the whole delicate intricate facade would have collapsed on its own weight, but that mistake is never made. The Uninvited never takes itself too seriously, it never takes itself too lightly. It is never merely heavy, the humor is never just thrown in; it is vitally needed, or this film would be unrelentingly depressing.

The spirits are just distinct enough to perceive as more than just light and shadow, but never more, they are a presence, but never quite of this world. They have influence over the living, but their power is that of suggestion and mood. At best they can make a rooms atmosphere change, close a door, cry in the night, fill a room with warmth and scent, or with malevolence, turn the page of a vital book at the right time. Even at the end you could just explain them away. Not easily, but if you needed to convince yourself…

And you might.

The cast, direction, effects, and script are uniformly perfect with a particular nod to Milland, Hussey, Russell, Crisp, and Skinner who all outdo themselves; especially Milland who does this so effortlessly you may miss how much of this films success depends directly on his performance, his connection with the audience, and his perfectly keyed emotional responses.

Milland’s timing as light comic actor, his more substantial talents, and his ability to play the hero are all on display. The finale of this film would not work if not for Milland’s ability to effortlessly switch from light comedy to intense fear in the same scene, virtually the same moment — making his defeat of Mary Meredith ironically perfect. Watch also for Dorothy Stickney, one of Miss Holloway’s patients, Miss Bird; it is a great bit part.

This was a major hit, though a follow up based on another Dorothy Macardle novel, The Unseen with Russell and Joel McCrea, isn’t anywhere near as good despite a Raymond Chandler screenplay, and the same director and production team.

Do yourself a major favor and find a copy of McArdle’s novel Uneasy Freehold (published in the US as The Uninvited). The film is very close, and the book is also one of the best of its kind ever written. I’ve seen too many ghosts to believe in them, but this movie and the novel always make me think about leaving a nite-lite on. There are more things in heaven and earth than Horatio, or I, care to think about.

And as frosting on the cake, “Stella by Starlight,” the haunting number Milland’s Rick is working on, was a major hit, much like “Laura” from that film. It is still a beautiful piece, and runs through the movie as a subtle musical cue leading the viewer to that cliff by the house and those final moments on a darkened staircase confronted with pure malevolence.

Cinematographer Charles Lang won a well deserved Oscar for this. His work is impressive.

Dracula, the Frankenstein monster, the Wolfman, they have nothing on Mary Meredith. Mary Meredith would unsettle Hannibal Lecter, the demon in The Exorcist would have been possessed by her. Mary Meredith like Du Maurier and Hitchcock’s Rebecca haunts this film even though you never see her save in a cold and forbidding portrait. She is a palpable presence; beside her Norman Bates mother was mother of the year, Joan Crawford was just a little strict, and Medea was having a bad day when she ate her children.

It is no easy trick to do that with a character who never fully materializes on screen.

The Uninvited is without question the finest ghost story of its era and for my money the finest ghost story ever filmed.

This isn’t Stephen King, Clive Barker, Peter Straub, V. C. Andrews, or Anne Rice. There are no vampires, there is no CGI, no fake blood is let on screen, no green pea soup expelled, nothing leaps off the screen at you. The Uninvited, just wraps it’s chilly hand around the base of your spine with frisson after frisson as visceral as a gut punch. Like Mary Meredith herself, once it has you it won’t let go long after the silver shadows on the screen have faded to nothing.

I have never watched this alone in the house at night. and quite frankly, I don’t intend to.

If that isn’t a tribute to a ghost story, I don’t know what is.

And try walking upstairs with only a candle to light your way when you have finished watching it.

Wed 29 Oct 2014

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[7] Comments

KEN ROTHROCK – The Deadly Welcome. Major Books, paperback original, 1976.

No matter how obscure a book or an author may be — and I believe this one qualifies on both counts — if there’s a PI in it, I will probably read it, or at least give it an all out try.

Rick North, who tells the story in first person, qualifies as a private detective, barely. He’s low man on the totem pole at Taber, Kline and North, an artist’s management firm based in LA, but he’s about to be booted out of the firm unless he finds out who has been threatening the life of Rory Maclaine, one of their clients and a comedian who’s just hit the big time.

Threats are one thing, but when Maclaine collapses and dies on stage after finishing his new act, North, who used to be a comedian himself until he found his career going nowhere, now finds he must solve the case, or else.

After a slightly shaky start, the tale that follows is solid enough, but a clutter of too any characters, all of whom seem to be acting individually in various and sundry ways, slow the story down to a near crawl around the two-thirds point. It has to be hard, in my opinion, for a new writer to maintain his (or her) momentum for the entirety of a full-length novel, no matter what kind of twist you plan on ending it with. And so it is here.

As for the author, Al Hubin in Crime Fiction IV, says that Ken Rothrock is probably Harley Kent Rothrock (1939-1999), but Google reveals no more. This was his only work of detective fiction, a good effort, but cliched. Maybe if North had been better at a quip (he isn’t), the ride would have been a little less bumpy.

Wed 29 Oct 2014

Reviewed by JONATHAN LEWIS:

DR. RENAULT’S SECRET. 20th Century Fox, 1942. J. Carrol Naish, John Shepperd, Lynne Roberts, George Zucco. Director: Harry Lachman.

“THE MASTER PLAN OF DR. FU MANCHU.” An episode of The Adventures of Dr. Fu Manchu. Original air date: 2 June 1956. Glen Gordon (Dr. Fu Manchu), Lester Matthews (Sir Dennis Nayland Smith) Clark Howat (Dr. John Petrie), Carla Balenda, Laurette Luez, John George. Guest Cast: Alan Dexter, Steven Geray (Mr. X). Based on characters created by Sax Rohmer. Director: William Witney.

One of the most terrifying tasks (in a good way) that a successful horror/thriller director can do is to transport the viewer into a claustrophobic, eerie, and self-enclosed celluloid universe in which evil both lurks in the shadows and hides in plain sight. And you don’t even need an oversized budget to do it and to do it extraordinarily well.

The trick, it would seem, is to keep the running time short, the atmosphere creepy, and the plot concerned with human physicality gone awry.

Such is the case for two gems I watched this Halloween week.

The first, Dr. Renault’s Secret, stars J. Carrol Naish and George Zucco in a cinematic admonition against tampering with the evolutionary demarcation that separates man from ape. Zucco portrays the eponymous Dr. Renault, an egotistical, sadistic, and downright creepy French scientist with a beautiful niece, Madeline (Lynne Roberts).

Naish, in a chillingly sinister role, portrays Noel, Renault’s simian-like assistant, a man of unbridled rage and murderous intent. From the moment you see him lurk about on the screen, you know there’s something just so terribly not normal about this tragic character. John Sheppard rounds out the main players as Dr. Larry Forbes, Madeline Renault’s American fiance.

Directed by Harry Lachman, Dr. Renault’s Secret has that I-know-it-when-I see-it film noir aspect to it. Light and shadow are utilized to convey meaning, there are numerous camera shots from oddly distinct angles, and Noel can certainly be considered to be the film’s doomed protagonist, a man trapped in an out-of-control world.

Also look for the noir-like mise-en-scene, the numerous staircases, doorways, and pathways that play prominent roles in conveying a story about Renault’s psychological descent into madness and Noel’s descent into savagery.

In “The Master Plan of Dr. Fu Manchu,†an episode of the television show, The Adventures of Dr. Fu Manchu, a physician is pressured into performing plastic surgery on a man long thought dead but who is very much alive: Adolf Hitler.

Fu Manchu, Satan incarnate, kidnaps Dr. Harlow Henderson, a friend of Petrie, and under the threat of torture, forces him to change the face of Hitler into the visage of an ordinary looking man, a person of unspeakable evil who could then safely hide in plain sight.

Directed by William Witney, this thrilling episode has it all: murder by tarantula, Cold War paranoia, Nazis in an underground South Pacific hideaway, and the psychologically discomforting notion that physicians, with the use of surgical implements, could fundamentally re-alter a man’s physical identity.

The last five minutes or so of this episode showcase Witney’s strength as a director of action sequences. After all, we get the thrill of witnessing Smith shoot and kill Hitler!

Tue 28 Oct 2014

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

BASIL DAVENPORT, Editor – Deals with the Devil. Dodd Mead, hardcover, 1958. Ballantine 326K, paperback, 1959 (abridged to only 12 stories).

I don’t deny the existence of a God, but I haven’t felt much need of one since I became a grown-up, so I leave the Almighty to those who do. But though I have never longed to find God, I have often wished there were a Devil.

Old Nick has brought so much to our culture that I feel some disappointment that His Satanic Majesty lacks the flesh-and-blood basis given to legends like Wyatt Earp and Richard III — and never have I felt this longing more keenly than while reading Basil Davenport’s excellent anthology Deals with the Devil.

In the excellent introduction to this volume, Davenport cites the Devil’s unique contributions to folklore and literature, from Genesis (Satan’s role in the Bible is small and open to debate, but he was always a rock star in the Christian church.) through Marlowe, Goethe and Stephen Vincent Benet.

Were he writing today, he might have included Ira Levin, William Peter Blatty and Stephen King, but I prize this collection for its antique charm, as Davenport lays out a spicy buffet of authors like Dickens, Dunsany, De Maupassant and the ever-popular Anonymous, to Asimov, Boucher and the underrated John Collier.

Davenport points out in his introduction that of the twenty-five tales collected here, the Devil loses out to God and Man in thirteen and wins in twelve. I also noted a tinge of sly humor running through the pages, perhaps best exemplified in Collier’s line, “Seated on a red-hot throne suspended over that pit whose bottomlessness I shall heartily envy.†(That one took a minute to sink in and be appreciated.)

The effect, however is to make the un-funny stories seem much more grim and unsettling, as Satan is sometimes depicted as an ethical square-dealer (albeit a sharp one) and sometimes as brutal, duplicitous and (worst of all) a bit stupid.

Whatever the case, a reader looking for a bit of atmospheric Halloween reading won’t go wrong here. As for me, I cherish the fantasy that when Steve posts this and my words light up the computer screen, I shall notice a bit of smoke in the room, a faint smell of sulphur, and hear a deep, ominous chuckle at my back….

Tue 28 Oct 2014

Reviewed by JONATHAN LEWIS:

WATERFRONT. PRC, 1944. John Carradine, J. Carrol Naish, Maris Wrixon, Edwin Maxwell, Terry Frost, John Bleifer, Marten Lamont, Olga Fabian. Director: Steve Sekely.

Sometimes casting one actor rather than another really can make or break a film that, on the surface at least, does not appear to have that much else going for it. In the case in Waterfront, a taut 1944 spy thriller about Nazi spies and German expatriates in wartime San Francisco, that actor is John Carradine.

Directed by Steve Sekely, a Hungarian filmmaker who made numerous low-budget American films, Waterfront stars Carradine as Victor Marlow, a ruthless dark-clad Gestapo agent tasked with hunting down the men responsible for stealing a list of Nazi spies in America from one Dr. Karl Decker (J. Carrol Naish), an optometrist with a waterfront practice.

The story begins with an armed robbery in the fog. The rather unobtrusive Decker, who we soon come to realize is a Nazi spy, is held up by a waterfront hoodlum. Too bad for him, as something far more valuable than money is taken from his possession. The thug takes his master spy book, a veritable listing of the Nazi agents in America.

Enter Marlow (Carradine), a lean, mean Nazi who will do whatever it takes to get the book back. He also, we soon learn, seems to have his eye on Decker’s position as head honcho in the San Francisco Nazi underworld. Marlow intimidates a local German woman who runs a boardinghouse, forcing her to provide him with lodging. As it turns out, the landlady’s daughter’s boyfriend has a pending business deal with one of the local, anti-fascist Germans involved with the theft of Decker’s book.

If it sounds complicated, it is and it isn’t. Suffice it to say that if you think too much about the plot, you begin to realize how preposterous it all is to have all these characters interacting in one small neighborhood of a large West Coast city.

Indeed, all things considered, Waterfront could not by any stretch of the imagination be considered a remarkably well-crafted spy tale. It does, however, benefit from a noir-like atmosphere and some exceptionally well-filmed sequences when the lanky Carradine, with his unmistakable voice, demonstrates just how well he portrays menacing characters. It’s a slightly clunky low-budget affair from PRC Pictures, but for what it is, it’s an enjoyable little wartime spy thriller.

Mon 27 Oct 2014

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[4] Comments

HUGH DESMOND – Death Walks in Scarlet. Wright & Brown, UK, hardcover, 1948.

Superintendent Alan Fraser, the leading detective in Death Walks in Scarlet is, I suspect, about as unknown a character who appeared in over 40 works of crime fiction as there could possibly be. Nor would even the most ardent reader of detective mysteries recognize the name of the author, who wrote several hundred of them — which is only a rough estimate. I didn’t take the time to count.

In other words, this is my candidate for the most obscure author of the month, although without looking back, I have a feeling there may be some strong contenders. The author’s real name was Kathleen Lindsay, who wrote crime novels under her own name, as Hugh Desmond, Elizabeth Fenton, Nigel MacKenzie and Mary Richmond. In fact one of the Alan Fraser novels was by Nigel MacKenzie. She was so prolific that she has her own Wikipedia page, which begins thusly:

“Kathleen Lindsay (1903 – 1973), was an English author of romance novels. For some years she held the record as the most prolific novelist in history. According to the

Guinness Book of World Records (1986 edition, where they refer to her as “Mary Faulkner”), she wrote 904 books under eleven pseudonyms. This record has since been surpassed.”

In case you’re wondering, no, I hadn’t heard of her either, before I tried to see if I couldn’t find out more about “Hugh Desmond” and coming up with a whole lot more than I expected.

I might have guessed that the author was a woman, if I hadn’t done the research mentioned above before I finished the book, but I was leaning that way, since the female characters in the story are all strongly depicted and play such key roles in the mystery. The superintendent’s wife, for example, does more in Death Walks in Scarlet than fix her husband’s supper when he comes home late at night after a long, hard day on the job.

Nor is she a mere sounding board for his concerns. It is at her suggestion that they go to a dinner party where they meet an invalid woman who is cared for by a trusted servant female and who has recently taken charge of a niece, who has come to live with them after the death of her father in France.

All strongly depicted characters, but what do they have to do with the gang of burglars who have become the bane of Fraser’s existence, especially once they have added murder to their long list of crimes? Fraser suspects they are former members of British military who, after the war, cannot find non-criminal employment to use their newly obtained talents on, and have thus turned to crime.

The connection between the two parts of the story is a key one, and even though the novel turns into more of a thriller — one including many deaths and more than one kidnapping — than a puzzle to be solved by pure deduction, it is a suspenseful one, with a twist that I almost but didn’t really see coming. I enjoyed this one.

Mon 27 Oct 2014

A DANGEROUS PROFESSION. RKO Radio Pictures, 1949. George Raft, Ella Raines, Pat O’Brien, Bill Williams, Jim Backus, Roland Winters. Director: Ted Tetzlaff.

First of all, I have to confess that I don’t understand George Raft’s popularity as a movie star, and I assume he had to have been popular at the time, or how did he manage to be given leading roles in as many movies as he was? His demeanor is stiff and wooden, he barely breaks a smile now and then, and when his does, his eyes don’t seem to match what his mouth is trying to convey.

But I will concede that he’s better in this low budget movie than others I’ve seen him in. The first part of A Dangerous Profession is also rather interesting, so let me tell you about that before getting into what eventually does go wrong, which it does, or at least I thought so.

Raft plays Vince Kane, the lesser partner in a bail bondsman company, the other partner, the one with the money, is Pat O’Brien, who is mostly out of the picture (figuratively as well as literally) for the first part of the movie. The husband of the woman that Kane once had a brief affair with (Ella Raines) has been picked up by the police in connection with a bond security robbery, which also left a policeman dead.

Bail is therefore set high, $25,000, and the man’s wife (and Kane’s former flingmate) and her lawyer can come up with only $4000. But out of the blue another lawyer who claims to be representing her brings in another $12,000. She says she doesn’t know anything about it, but Kane chips in another $9000 of the firm’s money, thus incurring Pat O’Brien’s wrath.

It’s a neat setup for a good story, and so it seems doubly so when the husband gets bumped off, and the police in the form of Jim Backus’s character isn’t happy about that. George Raft, in the guise of Vince Kane, is caught in the middle.

But the story goes downhill from here. The crooks are are dumb as Shinola, and whoever wrote the script had no idea what to do with Pat O’Brien’s character. He’s all over the map in terms of what his role is in this movie, good, bad or indifferent, and I’m not sure the fellow who wrote the script knew either. I kind of like guys who choose sides, or whose side is chosen for him, and we know whose side he’s on, especially when the movie’s over, if not before.

Nor do I, as a brief postscript, think that Ella Raines should be happy with whoever was in charge of photographing her. Only briefly are glimpses are seen of of her in full noirish beauty.

Sun 26 Oct 2014

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

VICTOR NORWOOD – Night of the Black Horror. Badger Books, paperback, 1961.

This is perhaps the finest novel ever written in the English language. Or perhaps not. Certainly it can’t be judged by the criteria we apply to most fiction: originality, prose, characterization or plot, yet I found it one of the most compulsively readable books I’ve opened this year.

A bit of research revealed that the first part of Night/Horror was stolen from a short story, “Slime†by Joseph Payne Brennan, and I mean Stolen, with characters and situations only slightly modified, as a formless, blob-like (Brennan got a cash settlement from the makers of that movie) deep-sea Thing gets blasted out of the ocean depths and lands in a swamp somewhere in the southern USA — one of those isolated rural burgs beloved in the Horror Genre, with the added twist that Author Norwood sometimes has his yokels lapse into British colloquialisms, as when the Sheriff tells everyone to park their cars with the bonnets close together.

Given such literary larceny and idiomatic ineptitude, Night of the Black Horror should have been a total waste, but — no kidding — I found myself completely gripped in its spell as the formless thing begins to creep out of the swamp at night, absorbing swine, ’gators, and the occasional landed gentry.

In short order it attracts the attention of a vacationing scientist, his handsome young assistant and (surprise!) beautiful daughter. A few more folks come to a (literally) sticky end before the Army comes in (“We’ll try it with flame-throwers and I’ll have men standing by with bazookas…â€) and things get really nasty.

Norwood shows real flair for moving a story along quickly, and he writes the nasty bits just visceral enough to be vivid without getting disgusting. And if the characters seem a bit pat, I had fun visualizing their cinematic counterparts. I could almost see John Agar, Faith Domergue and that grand old man of Sci-Fi, Morris Ankrum, strutting across pages I couldn’t turn fast enough.

Great literature? Hardly. But for a fast, fun read you couldn’t ask for better.

Sun 26 Oct 2014

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[3] Comments

Reviewed by DAVID VINEYARD:

VALENTINE WILLIAMS – Courier to Marrakesh. Hodder & Stoughton, UK, hardcover. Houghton Mifflin, US, hardcover, 1946. No paperback editions.

A huge figure stood in the doorway. It was a vast man in a black hat and a dark business suit, who leaned heavily on a cane. He might have been a tank, the way he shouldered Mülder aside as he came into the room, limping as he went. I instinctively glanced at his feet. My blood seemed to turn to ice when I perceived that one of them was encased in a monstrous surgical boot.

Enter one of the most despicable villains in popular literature, especially the popular literature between the wars, a clever, dangerous, fanatic, and self serving monster who serves his masters, but always serves himself first. Under the Kaiser there had been a code even he had to follow, but now he is Adolph Hitler’s top man.

“He is a monster, a wild beast, and everywhere he goes he leaves a trail of treachery, of broken faith, of blood—yes, blood!”

By now you may have figured out this is not a nice man. The fact is he could give Moriarity, Carl Peterson, and even Dr. Fu Manchu a run for their money. His name is Dr. Adolph Von Grundt, but he is much better known as …

“… Clubfoot does not change. Human beings — poor creatures with broken hearts like me — they change. But not Clubfoot. Because the man is not human.”

In Courier to Marrakesh the setting is mid-WWII in North Africa and Italy. Andrea Hallam is an American singer and guitarist touring with the USO, doing her best for the boys. She tried to join the WACS, but she was:

… sternly told at Washington that my job was to keep up morale, singing to the armed forces. They seemed to like me at the Stage Door Canteens, the camps and naval bases, not only my cowboy and hill-billy numbers, but even the old French and Italian ballads, the Spanish

saetas and Portuguese

fados, in my repertoire. It may have been my red hair, of course; our sailors and soldiers have never been known to have any particular allergy to redheads. But my heart was not at peace and I never rested until I persuaded Washington to send me overseas to sing at the camps.

Andrea is also looking forward to running into old friend Hank Lundgren.

If I had been the marrying sort I could have settled down with Hank Lundgren at Milwaukee. It was in the fall of ’39, soon after war broke out in Europe, that he came up with his proposal… I liked Hank tremendously, but the songs came first.

Andrea thought Hank, who had a business in radio before the war, was in communications, but when she meets dashing handsome gray eyed Nicholas Leigh, a young British officer, she discovers what he and Hank actually do: “I’m Intelligence, the same as Hank.” That’s certainly exciting, dull old Hank Lundgren in intelligence, who would have thought.

Andrea is soon up to her neck in dubious people, Countess Mazzoli, who claims to be an anti-Fascist Italian, and her son Captain Mazzoli among them, and the Countess has given Andrea a locket to deliver to a man named Safi, who is certainly suspicious, Peter Lorre type, you know. Then there is the Swiss Herr Ziemer who is to introduce her to Moroccan singer Shelika Zueima, a local artist Andrea has been wanting to hear. It is Zueima who will warn her about Clubfoot for the first time.

Soon enough Andrea is up to her lovely red hair in intrigue, enlisted by Leigh, Hank, and their buddy Major Riley (aka Snafu) in a bit of political intelligence. Andrea all on her own has stumbled on a nest of Nazi intrigue, and only just missed Clubfoot himself. They need to get her away and Naples sounds like the best place. Safu tries to explain to her the political situation she has stumbled on a struggle for power between the old Prussian guard of the German General Staff and Hitler.

This was soon to be the stuff of headlines as 1944 came to a close. The book came out in November of 1944 and the famous July Plot to assassinate Hitler led by Count Von Stauffenberg had only just happened.

“ …a strong anti-Hitler movement has developed among a small but influential group of the high-ups on the German General Staff. These Generals realise (sic) that Germany has lost the war; what they’re after now is to try to salvage as much as they can of the wreck. The plan is to throw dust in the eyes of the free nations by getting rid of Adolf and the Nazis and have the Generals fix the peace.”

Grundt and his boys are after an old drinking cup that contains something important and the stakes are high, winning the peace after the war.

“Hitler’s not the only danger to the future of the world. The reactionary elements everywhere are fighting a rearguard action to save the world from democracy, people who have this cock-eyed idea that a military government in Germany, purged of the Nazis, is preferable to a victorious Russia.â€

This is far above the usual chase for some super weapon or battle plans of most wartime spy thrillers. Whether Williams was in any way privy to it or not, these debates were actually going on during the war and fought out in the shadow world of intelligence. There are still those who would have preferred to rearm Germany and declare war on Russia despite the fact both sides had the bomb by the end of the war. There are still those who think we should have sided with Hitler against Stalin. Riley sums it up for her.

“In Marrakesh, lady, anything can happen. Through no fault of yours you’re up to the neck in this game of ours, and let me tell you, my dear, it’s a game with no punches barred. There’s nothing to choose between your Dr. Grundts and your Colonel von Rodes. These Prussian Army gangsters are fighting for their very existence…â€

Before it is over Andrea will fall in love with Nicholas Leigh, be captured by the Prussian side and threatened with torture, and be rescued, ironically, by none other than Clubfoot himself. Events move quickly and soon enough Andrea learns what is at stake.

“All the Nazi leaders keep dossiers against each other,” he (Hank) said. “Fritsch was supposed to have had one on Hitler. Sheer dynamite, if what they say is true — that’s why for years Hitler didn’t dare to touch him. Anyone who could have got hold of it could have blown Adolf sky-high… That Hitler dossier is right up our street. No need to publish anything; just see that selected extracts are shown to the right people, both in Germany and outside. That dossier is supposed to contain the complete file of Hitler’s dealings with the German industrialists who financed him, his correspondence with Mussolini, documents establishing his responsibility for the famous Party purge, details of his private fortune and where it’s tucked away abroad—gosh, in the Balkans alone it would be worth ten divisions of troops to us.”

Granted Dennis Wheatley did this same sort of thing, but Williams is a much more literate and smooth writer, and there are no huge chunks of undigested history to trip over in the narrative. It moves fairly fast, Andrea is an engaging and certainly different narrator/protagonist, and always, as in all of the Clubfoot novels, the shadow of Grundt’s lumbering figure hangs over all brilliant, threatening, and monstrous.

There’s a last minute desperate fight and rescue, but not quite soon enough, a happier ending than you might expect, and in the long run a better example of the WWII spy novel than you have any reason to hope for from the admittedly old fashioned Williams. Compare this to Wheatley’s Gregory Sallust novels or Oppenheim’s final novels at war’s beginning (The Last Train Out and The Shy Plutocrat) and you’ll see how literary and modern Williams reads in comparison. Wheatley still sounded as if it were 1939 in the 1960‘s.

Some discussion of Valentine Williams followed a recent review here of his collaborative novel with Dorothy Rice, The Fog, so I thought it might be of value to show one of the reasons Williams stuck with thrillers more than detective stories and was admired and enjoyed for them.

This book shows a style that embraced change and modernity, a willingness to experiment with a woman narrator and protagonist (she’s a pretty modern heroine, smart, tough, and capable, no swooning for Andrea) — and successfully — a pretty canny grasp of back room wartime politics, and Williams usual inventiveness.

He also does remarkably well with his largely American cast of characters, certainly better than most British writers of the era. John Buchan, a far better writer, didn’t do half this well with Hannay’s American pal John Blenkiron. It’s hardly revolutionary, but it is a good thriller in a long running series and an unusually fresh book for this late in the Clubfoot saga. Few thriller series that began in the grim shadow of the First World War were still this fresh and inventive mid way through the Second.

Sat 25 Oct 2014

Reviewed by JONATHAN LEWIS:

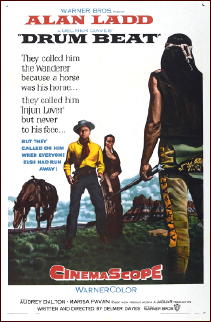

DRUM BEAT. Warner Brothers, 1954. Alan Ladd, Audrey Dalton, Marisa Pavan, Robert Keith, Rodolfo Acosta, Charles Bronson, Warner Anderson, Elisha Cook Jr. Screenwriter-Director: Delmer Daves.

If you’re not a Charles Bronson fan, you’re probably not going to care for Drum Beat all that much. If you are a Bronson fan, however, you’re in for a real treat in this extraordinarily scenic CinemaScope Western. Most of the movie is filmed outdoors and there are some great naturalistic settings.

Directed by Delmer Daves, the film’s top billed star is Alan Ladd, who portrays Johnny MacKay, an “Indian fighter.†His mission: bring peace between white settlers and Indians in southern Oregon, not far from the California border. His opponent is Captain Jack (Bronson), a renegade Modoc warrior whose arrogance, intransigence, and ruthlessness is on full display.

But make no mistake about it: Bronson steals the show in this one. He is a wild man, nearly as untamable as the natural settings in which he lives and breathes. But if anyone can break Captain Jack’s reign of terror it is going to be MacKay. So we know from the get go we’re in for an eventual showdown between the two men. And what a showdown it is! The two rivals eventually go at it in hand-to-hand combat as they cascade down a river. It’s but one extremely well filmed action scene in a movie replete with harrowing, often quite shockingly violent, action sequences.

Skilled character actor Robert Keith, who was simply brilliant as a criminal in The Lineup, which I reviewed here, portrays a settler seeking vengeance against the Modocs, while Irish-born actress Audrey Dalton portrays Nancy Meek, Johnny MacKay’s love interest. Their romance just doesn’t feel all that real, but is in many ways, a necessary ingredient in the overall plot.

Drum Beat isn’t without its flaws. The film does at times feel just a bit too predictable. At times, it also seems to borrow too heavily from John Ford’s classic, Fort Apache (1948). There’s even a scene in which MacKay tells a Calvary officer that, even though they aren’t visible, the Indians are certainly hiding in the rocks. John Wayne’s character famously said almost exactly the same thing to Henry Fonda’s character in that earlier film. There’s also the matter of the double cross, although in Drum Beat, it’s the Indians, not the Whites, who are the duplicitous ones.

All that being said, Drum Beat is a certainly an above average Western. The film’s best moment is when MacKay and Captain Jack meet in a Modoc dwelling early on in the film. It’s an exceptionally well-filmed scene and is an example of great staging. It certainly places the emphasis on these two characters. The struggle, tension, and grudging admiration between these two fighters make this somewhat lesser known Western worth a look.

Next Page »