January 2009

Monthly Archive

Sat 31 Jan 2009

Do you know what? This is the 1000th post to appear on this blog. Two years, one month and five days later.

I know, I know, if you check the URL for this one, it says it’s the 1005th, but I’ve written five that are still in limbo and have never been posted. They’re semi-ready, though; maybe I’ll get back to them someday and finish them up.

Some of the remaining 1000 have been deleted for one reason or another. I wrote one after I’d the flu for a day or so, and in it I described the dream I kept having over and over again — something about bricks in a wall — but I was still feverish when I wrote it and when I recovered, I decided that some things are best mentioned only once and then forgotten.

But not entirely. Even though you probably don’t remember it, I think it’s obvious that I still do.

I wish I knew when I started what I wanted to do with this blog, but in recent weeks I think it’s getting closer to whatever goal I didn’t have in mind back then.

I don’t know if that makes sense or not, but it does to me.

— Steve

Fri 30 Jan 2009

NICHOLAS FLOWER on Charles Williams:

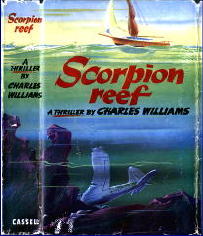

My father, Desmond Flower, was the Literary Director of Cassell at the time I joined the firm in the 1950s. He visited New York every year to buy books for UK publication from NY publishers and agents. On one of his visits he was given a copy of Scorpion Reef for consideration.

This, the Macmillan (NY) edition, must have been the first hardcover edition of a thriller by CW. My father liked it, bought the rights and we published it in 1956.

It was critically well received and this led to the idea of reissuing his Gold Medal paperbacks as hardcovers in the Cassell crime list.

As is clear from the order of their publication, there was no correspondence between the order of original Dell or Gold Medal publication and the order in which we republished them. Some of them were republished under their paperback titles, such as The Big Bite, but it was felt that some of the titles, particularly the “Girl” titles, were not right for the hardcover market.

It was at this point, before I took over editorial control of the Crime list in 1960, that I got involved with CW, because the pleasant task of thinking up new titles was left to me. Each time we were resetting a book for which we felt a new title was needed, I would write to CW with a suggestion and he accepted every one.

Those I remember putting to him include:

Operator [Cassell, 1958; previously Girl Out Back, Dell 1958]

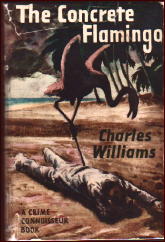

The Concrete Flamingo [Cassell, 1960; previously All the Way, Dell 1958].

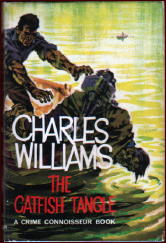

The Catfish Tangle [Cassell, 1963; previously River Girl, Gold Medal 1951].

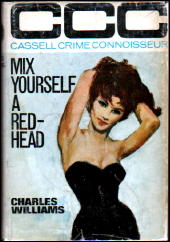

Mix Yourself a Redhead [Cassell, 1965; previously A Touch of Death, Gold Medal 1954]

The Hot Spot [Cassell, 1965; previously Hell Hath No Fury, Gold Medal 1953].

Because the decision to reissue earlier titles in hardcover, and to retitle some of them, had been taken by Cassell, the US hardcover editions of Gold Medal reissues followed within the same year. New titles, written by CW after 1958, such as Aground and Dead Calm, went straight into hardcover, the US edition preceding the Cassell edition.

The reissuing of the Gold Medal books in hardcover, many with new titles, played a crucial role in the continuation of CW’s success. It led to the creation of a new audience, not least through library sales. It brought him to the attention of critics in the mainstream and publishing trade press where, on both sides of the Atlantic, he was consistently well reviewed.

This rebirth of his books led in turn to their reissue, under the new titles, in two further paperback phases: first, following on directly from the hardcover editions, by Pan in the UK, and Pocket Books and Harper and Row in the US; then later, through another phase of reissues, in the 80s and 90s, by publishers such as Penguin and No Exit Press.

The photo attached is one I took of Charles Williams on the top floor of the Cassell building in Red Lion Square, London, in the early 60s.

On the literary side, I have always divided his thrillers, not into sea vs land, but into water vs land. In all the books which contain boats, fishing, water and swamp, there is a deeply nostalgic and pervasive atmosphere of mystery – smooth water providing both a feeling of calm and of hidden menace.

There is no better example of a water novel than what I retitled The Catfish Tangle, the title referring to the catfish which Shevlin catches for the restaurant at the head of the lake.

In the 60s, Cassell and Collins were the pre-eminent UK publishers of blockbuster novels. Our authors included Alec Waugh, Nicholas Monsarrat, Irving Stone and Irving Wallace. The last time CW visited our office, I put to him the idea that he could write a wonderful full-length novel using a liner as the setting.

And the Deep Blue Sea ((Signet, pb, 1971; Cassell, 1972) is, in my opinion, not really a sea novel; the liner in the book is merely a platform for psychological interplay and misdeeds. I do not think it is successful as a thriller, but it clearly shows what he could have achieved through his powers of characterisation had he been prepared to work on a bigger canvas.

Might it have revitalised his career? Sadly we shall never know. He said no; he was happy doing what he knew best and felt he was too stuck in his ways.

___

NOTE: For an essay by Bill Crider on Charles Williams, along with a complete bibliography, follow this link to the primary Mystery*File website.

___

[UPDATE] 02-01-09. After making a couple of minor edits in the piece above, Nicholas and I have been discussing some of the other books by CW that Cassell published. One of them was The Sailcloth Shroud, which was published first in the US in hardcover (Viking, 1960; Cassell, 1960).

No change in title was made for this one:

There are two others for which the titles were changed, but for these Nicholas says: “I did not think up the the titles [for these two books]. I have a feeling (no more than that) that CW may have retitled them himself.”

Stain of Suspicion [Cassell, 1959; previously Talk of the Town, Dell First Edition, 1958]

Man in Motion [Cassell, 1959; previously Man on the Run, Gold Medal, 1958]

Two additional books were published first as paperback originals in the US, then by Cassell in the UK. There were no changes in title for either of these:

The Big Bite [Cassell, 1957; Dell, 1956]

The Long Saturday Night [Cassell, 1964; Gold Medal, 1962]

[LATER.] 03-17-09. In his most recent email, Nicholas adds the following:

“I left Cassell in 1970 following the take-over of the company by Crowell Collier Macmillan of New York. By then all but one of CW’s novels, Man on a Leash, had been published.

“In 1965 the name of the crime list was changed to CASSELL CRIME and the decision was taken to reduce production costs by introducing a standard in-house series cover. The three band covers, which I designed, each featured a studio photograph incorporating elements of the story. The Hot Spot was the only CW thriller to appear with a CC series cover.”

[UPDATE #2] 09-11-10. Twelve covers are reproduced above, but Cassell actually published fifteen of Charles Williams’s thrillers, not including his comic crime stories, such as The Wrong Venus and The Diamond Bikini.

Thanks to the assistance of some online booksellers who graciously supplied us with the three previously missing, we can now display the covers of all fifteen:

Aground. [Cassell, 1961; Viking, US, hardcover, 1960; Crest s471, US, pb, 1961; Pan, UK, pb, 1969]

Dead Calm. [Cassell, 1964; Viking, US, hardcover, 1963; Avon G1255, US, pb, 1965; Pan, UK, pb, 1966]

Man on a Leash. [Cassell, 1974; G. P. Putnam’s Sons, hardcover, 1973; no paperback editions]

For these last three covers, thanks to Nigel Williams Rare Books, London, for the cover image to Aground; to Instant Rare Books of Auckland, New Zealand, for Dead Calm; and to The Antique Map & Bookshop, Puddletown, Dorset, for Man on a Leash.

Finally, a special note of thanks to Mark Terry of www.facsimiledustjackets.com, who earlier supplied the cover of Scorpion Reef, and to Bill Pronzini, who sent me all the others.

Fri 30 Jan 2009

MANNING COLES – Let the Tiger Die.

Doubleday Crime Club, hardcover, 1947. Hodder & Stoughton, UK, hc, 1948.

I was talking with a friend about mysteries the other evening, and of course the subject of authors who were popular back in the 30s, 40s and 50s came up. Both of us had fond memories of the Manning Coles–Tommy Hambledon stories, it turned out, the latter being one of England’s leading intelligence agents during World War II and the era that came along afterward.

Neither of could remember the names of his two amateur assistants, though: a pair of happy-go-lucky chaps whose gleeful approach to the spy game often bordered an sheer genius or lunacy, it’s hard to tell which.

In this adventure Forgan and Campbell (that’s their names) don’t appear until page 141, but from that point on, they simply take over the book. They’re more than mere catalysts in moving the story into high gear. They’re more active in what follows than Tommy himself, who seems more content, at least this time out, in forcing himself into outrageous situations and then sitting back to see what happens.

It begins with Hambledon on vacation, but just as it always happened to the Hardy Boys (but never to me when I was growing up), he spots something — three men obviously following someone who appears to be a German in Stockholm — and before he knows it, he is mixed up in an attempted abduction, a murder, and a mysterious package on his hands, plus a dying message from the Herr Goertz who was carrying it.

Massive coincidences quickly pile up — adrift in the Baltic, Tommy is picked up by a ship whose captain has just been swindled by the same person whose papers Tommy just happens to be carrying — but by sheer audacity Tommy soon finds himself infiltrating a gang of fascists who have not yet conceded the war is over.

Disguised as himself, if you can believe that — but somehow assumed to be someone else (and who that is he doesn’t learn himself until there’s only five pages to go), once again Tommy Hambledon and his friends save the day.

I don’t think I could ever convince myself that this is the way serious spy business is conducted, off the cuff and on a lark, so to speak, but it’s entertaining, the background of Europe just after the war feels exactly right, and Manning Coles is another author who doesn’t deserve to be as forgotten as I think he is.

— Reprinted from Mystery*File 33, Sept 1991 (revised).

[UPDATE] 01-30-09. And of course those last two words should read “they are” instead of “he is.” Manning Coles, as was well known even back than in 1991, is the joint pseudonym of two neighbors in Hampshire, England, Cyril Henry Coles and Adelaide Frances Oke Manning.

The earliest Manning Coles books weren’t as light-hearted as those that came along later. I think it took the end of World War II before that happened. But as far-fetched as the later ones always seem on the verge of becoming, they’re the ones that have stuck more vividly in my mind.

And I’m not the only one who remembers Tommy Hambledon and his cohorts fondly. The folks at Rue Morgue Press have reprinted five of them so far, mostly from his earliest anti-Nazi WWII days.

Fri 30 Jan 2009

JESSICA FLETCHER & DONALD BAIN – Murder She Wrote: A Palette for Murder.

Signet, paperback original. First printing, October 1996.

The first question that occurs to me as I sit down to write this review, and it hadn’t occurred to me before now, except in a nebulous sort of way, is just how many of these “Jessica Fletcher” books are there? They’ve seemed sort of generic and ubiquitous at the same time, and I never stopped to get them listed and enumerated. Until now. Take a look at the other end of this review…

… and now that your eyes are back,some historical perspective may be in order. The TV show itself, the one starring Angela Lansbury, was on the air for twelve seasons, from 1984 to 1996, with four made-for-TV movies appearing after that, the last one in 2003.

The first Murder, She Wrote novel came out in 1985, and there’s at least one that’s scheduled for 2009, a span of years that’s even longer than when the TV program was on the air. It’s quite a track record, and it certainly goes a long way in explaining the ubiquitousness I mentioned above.

Which of course got me to thinking. What other series of TV tie-ins has consisted of more books than this one with Mrs. Fletcher has?

To set some parameters, let’s restrict this question to detective novels. Otherwise in the field of science fiction, there is Star Trek, and we do not want to even begin to go there.

In the field of gothics, and books that are actually included in Al Hubin’s Crime Fiction IV, there are the Dark Shadows books, of which there 32 (at a quick, rough count). Good, but not good enough. There are 35 Murder, She Wrote books, or there will be soon.

If anyone can come up with a series I’m simply not thinking of — and, no, I don’t consider the Perry Mason paperbacks with photos of Raymond Burr on the back cover true TV tie-ins, or should I? — let me know.

As for the author, Donald Bain, he has his own website (and photo), and by following the link, you can find a complete list of all of the books he admits that he has written, and not all of them have been crime fiction, by any means. His bibliography also pointedly omits 24 books he wrote under another’s name but which he can not contractually reveal. Most of these books are (in all likelihood) the Margaret Truman books, of which Al Hubin says, again in the Revised Crime Fiction IV:

TRUMAN, (Mary) MARGARET (1924-2008). Despite the strenuous denial of Donald Bain, 1935- , q.v., the strong belief persists that he has ghost-written all the titles below…. (The year of her death appears only in the Addenda.)

Back up when I starting this review, which seems a long time ago already — you don’t know it, but it is now several days later, real time — I also called the books “generic” as well as ubiquitous, and perhaps I should apologize for that, even though I said “they’ve seemed,” since of course and/or as usual, this is the first one that I’ve read.

“Ubiquitous” I think I may have proven, but the case is far less solid when it comes to generic, unless of course you think that the TV show was generic, and maybe it was, but what TV show today exerts as much effort into actual deduction in terms of its detective work than Murder, She Wrote? Numb3rs, perhaps? Any others?

I’ll get back to this. To tell you something about the book I have just read, in it Jessica Fletcher is visiting the Hamptons (on Long Island), trying to get away from the hustle and bustle of the big city and secretly to try her hand at oil painting.

The latter effort fails — well, in fact both objectives fail — if getting away from the big city means staying away from murder cases — when the young model posing nude for Jessica’s class is found dead while taking a short break. (With careful camera angles, most of the activity immediately preceding could have been shown on television.)

But in any case it is thus that Mrs. Fletcher is introduced to world of modern art, including thefts (her own sketch of the dead girl included), forgeries and high finance, Long Island style.

She also tells the story in her own words, and what is quite remarkable is that Donald Bain as the author has her voice down cold. Perfect. To a T. From page 58:

“… One minute Miss Dorsey was very much alive and posing for fifteen fledgling artists. The next minute she was dead.

“I knew I could justify looking into her death based upon the theft of my sketch. Maybe I could find out who took it. Even more important, the sketch was now floating around the Hamptons. Where was it? And who had it now?

“I stopped going through my internal justification process, and decided to take a walk. It was sunny and warm outside, the sort of pretty day I’d counted on when deciding to vacation in the Hamptons.”

And then a second death occurs, suggesting that the first one was not a simple accident of some kind, as if we (the reader) did not know that already. Perhaps innate in the world of “cozy” detective novels, the death may have affected me more than it did anyone in the story, including Mrs. Fletcher, who had begun to know the second victim well. (Shouldn’t she have at least been angry about it?)

What I said about Donald Bain’s having his “co-author’s” voice down pat, he — at this relatively early point in the series — it does not seem to me that he has the mystery-telling (and solving) pattern of television series very well in mind at all.

Instead of calling the suspects together and recreating the crime scene (in flashbacks) and naming the killer as a result, we have Jessica going here and there on her own and in exceedingly dangerous places, not realizing as she should that a two-time killer is on the loose.

The ending is rather muddled altogether, in fact, and that I ending up skimming through it, rather than being transfixed with the unraveling, may tell you more about the mystery than anything else, I regret to say. I may read another, but without a push from some other direction, all things considered, it’s not as likely as it should be.

By JAMES ANDERSON —

The Murder of Sherlock Holmes (n.) Avon, pb, 1985.

Hooray for Homicide (n.) Avon, pb, 1985.

Lovers and Other Killers (n.) Avon, pb, 1986.

By DAVID GEORGE DEUTSCH —

Murder in Two Acts (n.) Star, UK, pb, 1986.

By JESSICA FLETCHER & DONALD BAIN —

Gin and Daggers. McGraw-Hill, hc, June 1989; Avon, pb, October 1990; Signet, pb, April 2000.

Manhattans and Murder. Signet, pb, December 1994.

Brandy and Bullets. Signet, pb, August 1995.

Martinis and Mayhem. Signet, pb, December 1995.

Rum and Razors. Signet, pb, April 1995.

A Deadly Judgment. Signet, pb, April 1996.

A Palette for Murder. Signet, pb, October 1996.

The Highland Fling Murders. Signet, pb, April 1997.

Murder on the QE2. Signet, pb, October 1997.

Murder in Moscow. Signet, pb, May 1998.

A Little Yuletide Murder. Signet, pb, October 1998.

Murder at the Powderhorn Ranch. Signet, pb, May 1999.

Knock ’Em Dead. Signet, pb, October 1999.

Trick or Treachery. Signet, pb, October 2000.

Blood on the Vine. Signet, pb, April 2001.

Murder in a Minor Key. Signet, pb, October 2001.

Provence to Die For. Signet, pb, April 2002.

You Bet Your Life. Signet, pb, October 2002.

Majoring in Murder. Signet, pb, April 2003.

Destination Murder. New American Library (NAL), hc, October 2003; Signet, pb, September 2004.

Dying to Retire By. Signet, pb, April 2004.

A Vote for Murder. NAL, hc, October 2004; Signet, pb, September 2005.

The Maine Mutiny. Signet, pb, April 2005.

Margaritas and Murder. NAL, hc, October 2005; Signet, pb, September 2006.

A Question of Murder. Signet, pb, April 2006.

Three Strikes and You’re Dead. NAL, hc, October 2006; Signet, pb, September 2007.

Coffee, Tea, or Murder. Signet, pb, April 2007.

Panning For Murder. NAL, September 2007; Signet, pb, September 2008.

Murder on Parade. NAL, hc, April 2008. Signet, pb, March 2009.

A Slaying In Savannah. NAL, hc, September 2008. Signet, pb, September 2009.

Madison Avenue Shoot. NAL, hc, April 2009

— April 2006 (revised)

[UPDATE] 01-30-09. Any updating has already been done, either in the course of the review, or in the subsequent bibliography. This post is long enough now without my needing to say more!

Thu 29 Jan 2009

Reviewed by MIKE GROST:

CAROLYN WELLS – Faulkner’s Folly.

George H. Doran Co., hardcover, 1917. Serialized in All-Story Weekly, September 8 to September 29, 1917.

Carolyn Wells’ Faulkner’s Folly (1917) is the first novel I have read by that author. It shows the frustrating mix of (artistic) virtue and vice that other commentators have discerned in her work.

The book is startlingly close to the traditions of the Golden Age novel. But it was written before Christie, Carr, Queen, Van Dine and other intuitionist Golden Age writers had published a line. And this is hardly Wells’ first work; she had been publishing for over a decade, since 1906, when this novel appeared.

The novel has an apparent medium who holds séances, etc., and whose “supernatural” gifts are ultimately explained naturally; this seems very anticipatory of both John Dickson Carr and Hake Talbot. Carr was in fact devoted to Wells’ works while growing up, and we know from both Ellery Queen and Carr biographer Douglas G. Greene that he was one of Wells’ biggest admirers. Many of Wells’ tales are impossible crime stories; she was apparently one of the first to expand this genre from the short story to the novel, following Gaston Leroux.

Faulkner’s Folly also anticipates the Golden Age in other ways. It takes place in an upper class country house, and draws on a closed circle of suspects of relatives, guests and employees of the murdered man. There is an atmosphere of culture to the novel, too; the murdered man was a great painter, and one of his guests is the widow of the architect who built his mansion. The whole novel is very close in tone to S.S. Van Dine; in fact it is one of the closest approximations in feel to his work among the mystery authors who preceded him.

Wells would certainly be classified as an intuitionist. She started by publishing in All Story magazine, one of the early pulp magazines that also featured the work of Mary Roberts Rinehart. But her work could not be more different from Rinehart’s.

There is no sign of an influence from Anna Katherine Green, or of scientific detection à la Arthur B. Reeve. Nor is there much suspense of any sort in Wells’ work. Instead, Wells’ book is squarely in the intuitionist tradition, and seems on the direct line to such later intuitionist writers of the Golden Age listed above.

The best part of Wells’ book is the finale, when the murderer is revealed and the various mysteries are explained. It reminded me of the pleasure I have received from the finales of Christie, Carr and other Golden Agers, when all is revealed.

Now for the down sides of Wells’ work. Her book is nowhere as good as a work of storytelling as the later authors we have mentioned. And her plot is nowhere as clever as these later authors, either. Bill Pronzini’s Gun in Cheek (1982), his affectionate but hilarious history of really bad crime fiction, points out other truly major flaws in Wells’ works.

Her impossible crime plots tend to depend on secret passageways. This gimmick was later, during the Golden Age, regarded as a cheat; the locked room novels of Carr and others often contain solemn assurances from the author that no secret passageways were found in the buildings where the crimes occurred. To be fair, Wells showed some real ingenuity in the use of such secret panels and doors; but this gimmick is likely to annoy modern readers.

We can compare Wells’ novel with “Nick Carter, Detective” (1891), an early series detective tale. The story opens with a “locked house” crime. Nick Carter suspects secret passageways, and sure enough he eventually finds the house to be riddled with them.

They are similar to the secret passageways Herman Landon used for his Gray Wolf stories in Detective Story in 1920. Detective Story was the first specialized mystery pulp magazine. So the impossible crime caused by secret passageways was a common coin of inexpensive mystery fiction.

Carolyn Wells also used secret passages for her locked room tales in the 1910’s, although she tended to employ Occam’s razor on them. She would employ the minimum number of passages need to commit the crime, often just one. It would be strategically placed in the only spot that would allow the crime to be committed.

There was a quality of ingenuity to her placement: it was not at all obvious that a secret passage anywhere would enable the crime to be possible; the revelation that a secret passage would make the crime possible would startle the reader at the end of the story. She achieves a genuine puzzle plot effect by this approach: where is the secret passageway, and how could any secret passage possibly enable this crime?

Thu 29 Jan 2009

AMBER DEAN – Snipe Hunt .

Doubleday Crime Club, hardcover, 1949. Reprinted in The Standard as the “Book of the Week” feature, September 30, 1950.

This one surprised me a bit. It starts out with a couple of G-men who are stuck in the basement of a New York City tenement on a stake-out, trying to stay alert in order to spot any of the members of a notorious gang of counterfeiters they’ve been tipped off about.

Just another dull procedural, I thought. The only noticeable complications concern the unlucky love life of one of the agents, undone by some typical Woolrichian vicissitudes of fate.

Then suddenly the scene shifts. To upstate New York, the Finger Lakes region, where a commandeered customs agent named Max, his wife whom he calls Mommie, and a pretty girl named Danny combine forces to show the federal men the local lay of the land.

What a snipe hunt is is a wild goose chase; there is also a humorously nosy neighbor who thinks that Max is just pulling her leg. But comedy, even such an incongruous concoction such as this, does not mix well with sudden spurts of nearly devastating disaster.

Maybe I’m just chagrined at being caught off stride like this.

— Reprinted from The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 3, No. 4, July-Aug 1979 (mildly revised).

[UPDATE] 01-29-09. I messed up big time when I wrote this review. It turns out that one of Amber Dean’s standard series characters is in the book, and she didn’t make enough impression on me even to note her name: Abbie Harris. Checking the blurb for the book from Ellen Nehr’s Doubleday Crime Club Compendium, Abbie almost assuredly is Max Johnson’s nosy neighbor.

Most of Amber Dean’s 17 mystery novels take place in upstate New York, not too surprisingly, since she herself lived in the Rochester area for most of her life, 1902-1985.

Abbie Harris was in eight of those books. From the Revised Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin, here’s a complete list:

HARRIS, ABBIE [Amber Dean]

Dead Man’s Float (n.) Doubleday 1944.

Chanticleer’s Muffled Crow (n.) Doubleday 1945.

Call Me Pandora (n.) Doubleday 1946.

Wrap It Up (n.) Doubleday 1946.

No Traveller Returns (n.) Doubleday 1948.

Snipe Hunt (n.) Doubleday 1949.

August Incident (n.) Doubleday 1951.

The Devil Threw Dice (n.) Doubleday 1954.

Thu 29 Jan 2009

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review

by George Kelley & Marcia Muller:

FREEMAN WILLS CROFTS – The Cask.

Collins, UK, hardcover, 1920. Seltzer, US, hardcover, 1924. Reprinted many times in both hardcover and paperback.

Freeman Wills Crofts’s first novel, The Cask, is considered by many critics, including Anthony Boucher, to be one of the best and most important books in the mystery genre.

The prime virtue of this and all the Crofts novels is their tight, logical plotting, in which every detail fits solidly and smoothly. His detectives work meticulously to piece the clues together, often in order to demolish a supposedly unshakable alibi; and because they are so logical, the endings are always exceptionally satisfying.

Early in his career, Crofts experimented with a number of sleuths, but in his fifth novel — Inspector French’s Greatest Case (1925) — he introduced Inspector Joseph French, who was to appear in most of his subsequent books. Like Crofts’s previous heroes, French is a bit of a plodder who slowly and carefully works his way step by step through the process of deduction to a natural conclusion.

In The Cask, the plot turns on alibis. When four casks fall to the deck of a ship during unloading, two of them leak wine, one is undamaged, and the last leaks sawdust. This last cask is examined more closely, and gold coins and the fingers of a human hand are found. But before the cask can be completely opened, it vanishes.

Inspector Burnley of Scotland Yard is assigned to this bizarre case. Using the few clues available to him, he is able to locate the missing cask. And when it is opened, Burnley finds the body of a young woman who has been brutally strangled.

There are no clues to the victim’s identity, so Burnley goes to Paris, where the cask was assembled. What follows is a detailed, complex investigation, involving timetables, a performance of Berlioz’s Les Troyens, and a group of suspects with a multitude of motives.

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

Thu 29 Jan 2009

Posted by Steve under

ReviewsNo Comments

Reviewed by JUERGEN LULL:

FREEMAN WILLS CROFTS – Anything to Declare?

Hodder & Stoughton, UK, hardcover, 1957. Reprint: House of Stratus, UK, softcover, 2000. No US edition.

Anything to Declare is the last of Crofts’ detective novels and one of the least successful. One third of the book is taken up by giving a detailed account of the launching of a smuggling racket. The scheme involving pleasure cruises up the Rhine to Switzerland seems clever enough but is not really up to the standard of Croftsian gangsters.

Take for instance the problem of getting the stuff aboard. This was done much better in the early Crofts The Pit-Prop Syndicate. In this late novel a blackmailer tumbles to it by accident and later the Swiss customs also have no problem finding out.

The blackmailer has to be eliminated and the reader is fully aware of who does it and how it is done. Part 1 ends with a real surprise for both readers and murderers: a second blackmail attempt.

In part 2 Inspector French is called in. Evidence is gathered and the right conclusions are immediately drawn. Through the interference of the customs officials the gang is arrested before sufficient evidence to convict them of the murder is collected.

French deplores this but is able by luck and his usual ingenuity to supply the necessary evidence and by a typical tour de force even the body of the murdered blackmailer.

I admire Crofts but couldn’t find much here of what I appreciate in him: the surprises, the dead ends, French’s moments of despair. All this is missing. Those who don’t like Crofts will find themselves confirmed. Those who do may find still enough to enjoy the book.

Wed 28 Jan 2009

Posted by Steve under

ReviewsNo Comments

A REVIEW BY MARY REED:

ROBERT BARR – Revenge! Chatto & Windus, UK, hardcover, 1896 (shown). Stokes, US, hardcover, 1896.

As readers no doubt realise, the theme of this collection is the many and varied forms of revenge, some of them more inventive than others. A few thoughts on its contents follow:

“An Alpine Divorce.” A woman is dead but it suicide or murder? [The English Illustrated Magazine, Oct 1893.]

“Which Was The Murderer?” Will the man whodunnit escape justice via a legal loophole?

“A Dynamite Explosion.” How might you destroy a cafe under police guard, particularly when you live in a flat above it?

“An Electrical Slip.” Revenge carried out by a particularly well-placed relative of the victim.

“The Vengeance of the Dead.” A woo-woo tale wherein a disgruntled chap punishes his cousin and the lawyer who won the cousin’s case against him. [The English Illustrated Magazine, May 1894.]

“Over the Stelvio Pass.” But will the newlyweds be able to pass safely over it?

“The Hour And The Man.” A condemned prisoner escapes from prison. [The English Illustrated Magazine, Aug 1894.]

“And the Rigour of the Game.” A young man does not gamble or imbibe at his club, why does he attend it?

“The Bromley Gibberts Story.” An author planning a murder rampage calmly describes its details to an editor beforehand.

“Not According to the Code.” Collar manufacturers fall out and it all ends in tears. [Black and White, 31 June 1895.]

“A Modern Samson.” A member of the Alpine Corps attempts to escape a court martial by scaling a mountain on the border with Italy.

“A Deal On ’Change.” Wall Street magnate craftily ensures his daughter-in-law is not shunned by society.

“Transformation.” An inventive watchmaker extracts justice for his brother’s death. [The Strand, June 1896.]

“The Shadow of the Greenback.” Under a man’s will the man or men who kill his murderer will receive $50,000.

“The Understudy.” An actor steals the identity of a missing African explorer but with the best of intentions. [The Strand, Dec 1895.]

“Out of Thun.” A young woman collects marriage proposals when conducting research for, well, you’ll see. [McClure’s, July 1896.]

“A Dramatic Point.” Two actors argue about a piece of stagecraft.

“Two Florentine Balconies.” It would be wise not to mess with Venetian ladies….

“The Exposure of Lord Stansford.” Lord Stansford gets an interesting offer. [The Strand, Aug 1896.]

“Purification.” And it’s also best to avoid aggravating jealous Russian women.

My verdict: To describe the stories more than I have would give away much of their content and then a host of “continential objurgations” (a wonderful phrase stolen from one of the above yarns) would surely fly about.

However, I can reveal a number of these tales have twist endings and I found it an enjoyable collection to dip into at odd moments.

Etext: http://www.gutenberg.org/dirs/8/6/6/8668/8668.txt

Wed 28 Jan 2009

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review by Max Allan Collins:

JOHN B. WEST – An Eye for an Eye.

Signet #1642, paperback original; 1st printing, February 1959, plus at least one reprint edition.

John B. West was a man of many talents and achievements: A doctor, he was both a general practitioner and a specialist in tropical diseases; he was also the owner of a broadcasting company, manufacturing firm, and hotel/restaurant corporation. He lived in Liberia, was black, and late in his life — as a pastime, apparently — wrote novels about white private eye Rocky Steele, of New York City.

West appears to have been used by Signet Books as an attempt to fill the gap when their star seller, Mickey Spillane, stubbornly refused to write any more novels (until The Deep in 1960, that is). While the Rocky Steele novels were never any real competition for Mike Hammer (or anyone else), the six titles in the series did go through various printings and editions.

An Eye for an Eye, the first Rocky Steele adventure — in which for no particular reason the private eye avenges the death of the blond, beautiful, and wealthy Norma Carteret — is singled out here arbitrarily, as all of the books seem to be of a similar “quality.” (One book, the posthumously published Death on the Rocks, 1961, does have an African setting to distinguish it.)

While unquestionably lower-rung Spillane imitations (like Mike Hammer, Rocky Steele smokes Luckies, packs a .45, refuses the advances of his lovely secretary, has a loyal police contact, etc.), the West novels are goofily readable, as Rocky Steele teeters between the violence and revenge of Hammer, and the broads and campiness of Shell Scott.

The world West creates (actually, re-creates) is pure pulp fantasy, and makes the work of Carroll John Daly read like documentaries. The energetic pulpiness of the plots, and West’s confident, tin-ear, tough-guy dialogue (“Mercy! That rat didn’t know what the word meant, and I wasn’t gonna teach him.”) gives his private-eye stories the same sort of appeal as Robert Leslie Bellem’s Dan Turner tales and Michael Avallone’s later Ed Noon novels.

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

Next Page »