January 2007

Monthly Archive

Wed 31 Jan 2007

As you will have read in every newspaper in the country today, author, screenwriter and playwright Sidney Sheldon died yesterday at the age of 89.

In all likelihood, the average person (not you), having glanced at the headlines and the first few paragraphs without reading further, will think of Mr. Sheldon as an author of powerful blockbuster bestsellers a lot more than they’ll remember him as a writer of crime fiction.

If that is the case — and who knows, I may be wrong — I suspect it’s because that same hypothetical average person, when confronted with the phrase “crime fiction,” thinks primarily of “detective fiction,” and of Agatha Christie, Perry Mason and Spenser: For Hire, for example, but none of which (or whom) were Mr. Sheldon’s model, style or forte.

No matter. Sidney Sheldon was a crime fiction writer. Most of his novels were strongly based on criminous activities of all sorts, including (and especially) murder and its aftermath, often dealing with the rich and famous, beginning with his very first novel, The Naked Face, which earned him the Edgar for that year’s Best First Novel from the Mystery Writers of America.

From the wikipedia website is a synopsis of the story line:

“Judd Stevens is a psychoanalyst faced with the most critical case of his life. If he does not penetrate the mind of a murderer he will find himself arrested for murder or murdered himself…

“Two people closely involved with Dr. Stevens have already been killed. Is one of his patients responsible? Someone overwhelmed by his problems? A neurotic driven by compulsion? A madman? Before the murderer strikes again, Judd must strip away the mask of innocence the criminal wears, uncover his inner emotions, fears, and desires-expose the naked face beneath…”

From Allen J. Hubin’s Crime Fiction IV is a list of Mr. Sheldon’s work that correctly belongs to our field, ignoring all of the work he did as a screenwriter. (The hyphen before two titles indicates marginal crime content.)

SHELDON, SIDNEY (1917- )

* Redhead [with Herbert Fields, Dorothy Fields & David Shaw] (play) Chappell 1960 [London; 1905 ca.]

* The Naked Face (n.) Morrow 1970 [New York City, NY]

* The Other Side of Midnight (n.) Morrow 1974 [Catherine Douglas]

* Bloodline (n.) Morrow 1978

* Rage of Angels (n.) Morrow 1980 [New York City, NY]

* If Tomorrow Comes (n.) Morrow 1985

* Windmills of the Gods (n.) Morrow 1987

* The Sands of Time (n.) Morrow 1988 [Spain]

* Memories of Midnight (n.) Morrow 1990 [Catherine Douglas]

* The Doomsday Conspiracy (n.) Morrow 1991

* -The Stars Shine Down (n.) Morrow 1992

* Nothing Lasts Forever (n.) Morrow 1994 [San Francisco, CA]

* Morning, Noon and Night (n.) Morrow 1995

* -The Best Laid Plans (n.) Morrow 1997 [Dana Evans]

* Tell Me Your Dreams (n.) Morrow 1998 [California]

* The Sky Is Falling (n.) Morrow 2000 [Dana Evans]

To which I can add the following books published after the year 2000:

* The Sky is Falling (2001) [Washington anchorwoman Dana Evans]

* Are You Afraid of the Dark? (2004)

Two books, Catoplus Terror (a novel about a former spy attempting to apprehend Carlos the Jackal) and The Pavid Pavillion, are not written by Sidney Sheldon but are said to have been done by someone else who published them under his name. (Someone will have to enlighten me on these two books, as I cannot find copies of either of them offered for sale on the Internet.)

From today’s obituary for Mr. Sheldon in the New York Times, I offer this excerpt about his writing:

Sheldon’s books, with titles such as

Rage of Angels,

The Other Side of Midnight,

Master of the Game and

If Tomorrow Comes, provided his greatest fame. They were cleverly plotted, with a high degree of suspense and sensuality and a device to keep the reader turning pages.

“I try to write my books so the reader can’t put them down,” he explained in a 1982 interview. “I try to construct them so when the reader gets to the end of a chapter, he or she has to read just one more chapter. It’s the technique of the old Saturday afternoon serial: leave the guy hanging on the edge of the cliff at the end of the chapter.”

Analyzing why so many women bought his books, he commented: “I like to write about women who are talented and capable, but most important, retain their femininity. Women have tremendous power — their femininity, because men can’t do without it.”

For Mr. Sheldon’s credits in the world of TV and movie entertainment, I will send you to IMDB. Of the various series and films he worked on, the one for which I’d remember him most is Hart to Hart (1979-1984)the TV series he created starring Robert Wagner and Stefanie Powers, with made-for-TV movies continuing on through 1996. Fluff, perhaps, but high-powered (and highly enjoyable) fluff, and they did solve crimes.

For even more on Mr. Sheldon’s long career, you could not do better than to start with his own website, then head to a February 2006 interview with him by Kacey Kowars from which the following excerpts are taken:

KK: You were not pleased when

THE NAKED FACE, your first novel, sold 17,000 copies. Could you explain that for your readers?

SS: I thought it was a failure. The publishers were pleased. It won The Edgar Award for best first novel. But my television shows [I Dream of Jeannie], were being watched by 20 million people every week.

but later:

KK: Looking back over your career it seems you found the greatest satisfaction in writing novels.

SS: Yes, no question. When you write a screenplay you write in shorthand. You don’t say that your hero is tall, lanky, and laid-back. You might be thinking of giving the script to John Wayne and they give it to Dustin Hoffman. So you generally characterize it. In a novel it’s just the opposite. If you don’t put those things down your reader won’t know what you’re talking about.

KK: Is there one thing you’re proudest of as a writer?

SS: Finishing a novel when I was certain I didn’t have the talent to be a novelist. That was THE NAKED FACE.

UPDATE [02-01-07] On his blog, which you should visit every day, Ed Gorman gives a blunt but hugely accurate assessment of Mr. Sheldon’s career, then compares the comments he’s received on his death with those given Harold Robbins. Two writers whose fictional work took place in the same strata of society, two wholly different reactions to their passing.

Tue 30 Jan 2007

From a notice in the New York Times —

Allan Barnard, who was born in Madison, Wisconsin on August 8th, 1918, died on Monday, January 22nd of complications from Parkinson’s disease in Forest Hills, New York. Allan was married to his beloved wife Polly Barnard for 56 years. Allan was a book lover, author, editor and mentor whose publishing career spanned five decades. At the time of his retirement he was a Vice President and Associate Editorial Director at Bantam Books.

With all of these years in the world of publishing, Mr. Barnard could very easily have had many connections to the world of crime fiction, but the only one that appeared under his own name is –

THE HARLOT KILLER. Dodd Mead, hc, 1953. Dell #797, 1954. Paperback. An anthology of fact and fiction relating to Jack the Ripper.

Introduction, by the editor

Alan Hynd: Murder Unlimited (fact)

Dion Henderson: The Alarm Bell

Willam Sansom: The Intruder

Anthony Boucher: The Stripper [as by H. H. Holmes]

Richard Barker: The Jack the Ripper Murders (fact)

Kay Rogers: Love Story

Thomas Burke: The Hands of Mr Ottermole

Theodora Benson: In the Fourth Ward

Mrs Marie Belloc Lowndes: The Lodger

Edmund Pearson: “Frenchy” – Ameer Ben Ali (fact)

Unknown: Jack El Destripador [translated by Anthony Boucher] (fact)

Edmund Pearson: Jack the Ripper

Robert Bloch: Yours Truly, Jack the Ripper

Data taken from a listing on ABE and Index to Crime and Mystery Anthologies, Contento & Greenberg.

A earlier anthology, Cleopatra’s Nights (Dell #414, pb original, 1950) contains 13 stories and articles about the famous Egyptian queen. None seem to be crime-related, except possibly “A Toast to Murder” (from Queen Cleopatra) by Talbot Mundy.

Tue 30 Jan 2007

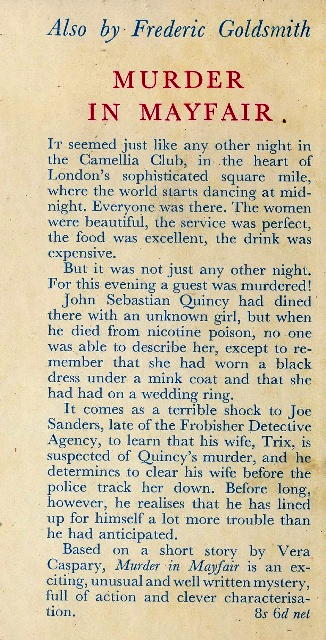

Regarding my previous posts on Frederic Goldsmith and his mystery novel Murder in Mayfair, primarily this one, Jamie Sturgeon sent me the following email:

By chance whilst going through my boxes of books I found a had a copy in dust wrapper of Frederic Goldsmith’s

The Smugglers. I have scanned the blurb for

Murder in Mayfair which was on the rear flap and attached it. The printed dedication in the book is to I.G., his father I presume. I did have a copy of

Murder in Mayfair in a previous catalogue but I sold it.

In the pair of emails that follow, Jamie added:

Reading the blurb I wonder if the book could be based on the short novel by Vera Caspary,

Lady in Mink? The US edition (book club only) was

The Murder in the Stork Club.

and

If

Murder in Mayfair is a re-write of

The Murder in the Stork Club, apparently the Caspary story first appeared in

Good Housekeeping magazine (I did a google search).

Regards,

Jamie

Comparing the pair of titles for Caspary’s book with the story line given in the blurb, it certainly looks like a match to me. I’m convinced. Thanks, Jamie! With this to go on, I also found the Good Housekeeping citation, from a Gutenberg list of copyright renewals:

R571103.

The Murder in the Stork Club. By

Vera Caspary. First appeared in Good

housekeeping magazine. NM: additions

& revisions. © 19Sep46; A8155.

Vera Caspary (A); 1Feb74; R571103.

Case closed?

Mon 29 Jan 2007

As far as the individual entries in Al Hubin’s Crime Fiction IV are concerned, it’s easy to forget that there a life behind each and every one of them. There’s always much more than the listing can ever say, taken in isolation by itself. Here’s an example. The entry for Muriel Davidson looks like this:

DAVIDSON, MURIEL (1924-1983)

* The Thursday Woman (n.) Atheneum 1979 [Los Angeles, CA]

* -Hot Spot (n.) Marek 1980

* ’Til Death You Do Pay (n.) Marek 1981

Two books which fall into the category of crime fiction, plus a third that’s only marginally so. The year of her birth, and the year of her death. You’d read this, glance at it for up to, say, several seconds, and then you’d go on to the next one, whichever the next one might be.

Unless you were looking for her entry with a specific reason in mind, and until you happened to want more and decided to Google her name. There is another Muriel Davidson who has something to do with the Canadian census, and you’ll going to have to screen her out. Then you come to an entry that looks promising, you click on it, and that’s when you discover, quoting the following news item in the New York Times:

AROUND THE NATION; Television Executive Found Slain on Coast

AP. Published: September 27, 1983

A television executive who had reported receiving crank telephone calls was slain at her home in fashionable Benedict Canyon, the police said today.

The police discovered the body of the executive, Muriel Davidson, 59 years old, at 1:45 A.M. today, Lieut. Dan Cooke said. There were no signs of a struggle. Neither the cause nor time of death was disclosed.

Mrs. Davidson recently signed with Jay Bernstein Productions as vice president of film and television development.

She wrote three mystery novels, The Hot Spot, The Thursday Woman and ’Til Death Do You Pay.

Her husband, Bill, is a contributing editor to TV Guide.

A followup story appeared the next day:

AROUND THE NATION; Arrest Made in Slaying Of Hollywood Writer

UPI. Published: September 28, 1983

A former aerospace worker who had received alcohol rehabilitation counseling from Muriel Davidson, a writer who published celebrity profiles and crime exposes in national magazines, was arrested today and charged with slaying Mrs. Davidson, who was also a television executive.

The suspect, Robert Thom, 51 years old, was arrested at his home in Pasadena at 4:30 A.M. on information received from relatives and friends of Mrs. Davidson, who was found Monday shot to death at her home.

To say that this was unexpected would be an understatement of some magnitude, and that’s putting it mildly.

Now the reason I was looking up Mrs. Davidson was that I was doing some research on a made-for-TV movie entitled The Wednesday Woman, which was supposedly based on her novel The Thursday Woman, included in CFIV and mentioned in the first Times article above. I kept looking, hardly expecting to discover anything else of significance. That a mystery writer was murdered herself was unusual enough. That there was a second chorus coming would never have occurred to me. (You may remember the incident yourself, though, especially if you were living on the West Coast at the time.)

It turns out that the made-for-TV movie, The Wednesday Woman, (CBS; Wed., May 24, 2000, 9 p.m.) if I am understanding the course of events correctly, was not exactly based on Mrs. Davidson’s book, but on her life, which in turn imitated the book that she had written earlier, The Thursday Woman. The movie was fiction based on a real-life sequence of events, which tragically mirrored the earlier work of fiction.

I don’t suppose I’m making myself as clear as I should be. I realize this because it took me a while myself to put the chain of events into some sort of order. The website that seems to tell the story best is this one, but allow me to quote the essential passages, and then if you’re so inclined, you should certainly go read the rest of the story for yourself.

First, however, a quote from the book itself:

“The most absorbing compelling novel I have read in years. It reminds me of the psychological novels of Georges Simenon.” Dr. William Nolen. Pure chance takes an average woman, Martha, into the courtroom of wife-murderer Everett. She has visceral sexual reaction to the accused criminal and becomes obsessed with “love” for a man she doesn’t know…

And now the chain of events that I mentioned:

(1A) In addition to TV scripts, celebrity profiles and other magazine articles and books, the real Davidson wrote a novel titled The Thursday Woman, about an addictive woman who has an affair with a dangerous fruitcake.

(1B) Besides writing for a magazine, the movie Muriel (played by Meredith Baxter) writes a novel with a similar plot titled The Wednesday Woman.

(2A) The real Muriel was murdered by Robert Thom, an alcoholic whom she met at a hospital where she counseled alcoholics once a week. A police report called the two “quite close.” A county probation officer said that just prior to her murder she had tried to sever her sporadic sexual relationship with Thom, who pleaded no contest to second-degree murder and was given a sentence of 17 years to life.

(2B) In the movie, Muriel is a recovering alcoholic, as is her psychotic lover (Peter Coyote) who tries to kill her after she wants to end their relationship.

(3A) and (3B) The kicker that comes next, is that the real life Muriel is murdered. In the movie, she is not, to widespread critical disapproval. If you are portraying real events as closely as this movie does, they said, how can you get away with changing the ending, even if it’s one that leaves the viewer pleased and satisfied that everything in the end, um, ended well?

You’ll have to answer that one yourself. I can’t give you any advice. I’m still marveling over the sheer audacity of real life to imitate fiction so closely in the first place, in this one single secluded entry in CFIV.

—

UPDATE [01-30-07] From a brief email sent by Victor Berch:

The California Death Index gives MD’s birth date as March 21, 1923; born in St. Paul, Minnesota. This seems to be verified in the 1930 US Census taken on April 8, 1930, where her age is given as 7 years old. Her maiden name was Friedland, so her entry should read:

DAVIDSON, MURIEL (FRIEDLAND) 1923-1983.

Mon 29 Jan 2007

This post began as an UPDATE to be found at the end of the previous one, but as I kept writing, it became long enough, I thought, and substantiative enough, to survive on its own. And so, on its own two feet, here it is:

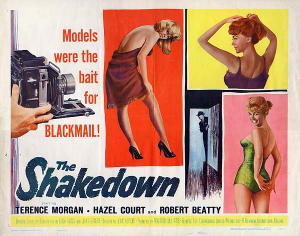

Taken from an email message from Al Hubin this morning: “Looks good. The only connection you haven’t made is that Murder in Mayfair was reportedly the basis for the movie “Hour of Decision” (Tempean, 1957).”

>> No, I didn’t catch that, and I’m certainly happy to know about it. When I checked how many copies of Murder in Mayfair were offered for sale yesterday on the Internet, the answer was none. Zippo. If someone were interested in knowing what the book’s story line was, all I could offer right now in reply are the comments of a single viewer on IMDB, which I’ll add below. And, yes, I know that the movie may be NOTHING like the book, but here goes something better than nothing, at least:

“This is a fairly routine though watchable whodunit that is notable mainly for the nearly salacious-for-the-time talk about the womanizing habits of a gossip columnist who gets murdered. Oh yes, the ever enticing Hazel Court is present as a past amour of the now-dead rakish fellow who tries to avoid suspicion for his murder. Her husband [Jeff Morrow] investigates so as not to have his honey nabbed by the coppers. London locations make it watchable.”

To which I add, ah yes, Hazel Court. I remember her from a short-lived TV series called Dick and the Duchess (CBS, 1957-58). It was an American series filmed in England and was mostly a comedy, but with criminous overtones.

Hazel Court’s co-star was Patrick O’Neal, who played Dick Starrett, an American insurance claims investigator based in London and married to an Englishwoman, the “duchess” of the title. That is to say, his wife Jane, whose efforts to help her husband invariably ended in disaster.

I may be the only person I know who remembers this series, but even though I was only 15 or 16 years old at the time, I think that I was slightly in love with Hazel Court. Yes, she was too old for me, but at that age what possible difference could a few years make, and a distance of only a few thousand miles away … ?

Thus began a lifelong love of British crime fiction. And yes, I do digress.

Sun 28 Jan 2007

Even though Allen J. Hubin’s work on Crime Fiction IV is nominally closed, he is still accumulating Addenda for his massive bibliography, as I’ve mentioned before, and actively so at that. The Internet is a massive tool to have at your disposal, especially Google, as everyone reading this must surely know — an enormously valuable implement for scooping up data and facts that simply wasn’t available when most of the work on the book was being done.

In Al’s case (and mine as well, if truth be told) he can now type in the name of an author whose vital statistics are scanty or non-existent (birth date, year of death, some biographical details) and/or the title of one of their books, and see what shows up.

Sometimes you get nothing at all, and sometimes – if the name is too common – you get too much. It’s impossible, for example, to sort through all of the Bill Joneses of the world.

Sometimes, however, you hit upon a nugget or two, or even more. Case in point. At the present time, or not until a couple of days ago, nothing was known about:

GOLDSMITH, FREDERIC

* * *Murder in Mayfair (Allen, 1954, hc) [London] Novelization of a short story by Vera Caspary, q.v.

* * *The Smugglers (Allen, 1955, hc)

On the web now, though, is a site belonging to Paul K. Lyons which includes, among other things, pages of information for over 500 diarists. Besides writing a small amount of fiction, Paul has been a diarist himself since 1974, and he is in the process of making the entries available online.

In January 1981 he happened to be reading a book called Murder in Mayfair (see above) and wrote about it in his diary. One line, and Google picked it up: “In the British Library I’ve been reading Murder in Mayfair written by my father, Frederic Goldsmith.”

Al spotted this, immediately emailed Paul and received this reply:

“My father Frederic Goldsmith wrote

Murder in Mayfair published 1954, London, by W. H. Allen and

The Smugglers published 1955, London, by W H Allen.

“He was born in 1925, in Vienna, moved to the UK during his teens (taking on British citizenship which he retained throughout his life), and died in the US in 1989. His wife, Gail Goldsmith, lives in New York.

“His father Isadore Goldsmith (IG) was a film producer, and IG’s second wife, Vera Caspary, was an American author (Laura).”

[UPDATE: In a later email to me, Paul added the following:

“I incorrectly spelled my grandfather’s name when writing to Al. He was known as Igee, but his first name was Isidor (not Isadore). It’s possible I picked up this mistake from IMDB, which has the same mistake.” ]

And there’s the connection with Vera Caspary. Here’s one of that lady’s entries in CFIV:

Bedelia (Houghton, 1945, hc) [Connecticut; 1913] Eyre, 1945. Film: Corfield, 1946 (scw: Vera Caspary, Moie Charles, Herbert Victor, Roy Ridley,

Isadore Goldsmith; dir: Lance Comfort).

Emphasis mine. And here’s Isadore Goldsmith’s full entry in www.imdb.com:

Producer – filmography

1. The Tell-Tale Heart (1953/II) (producer)

2. The Scarf (1951) (producer) (as I.G. Goldsmith)

… aka The Dungeon

3. Three Husbands (1951) (producer) (as I.G. Goldsmith)

… aka Letter to Three Husbands

4. Out of the Blue (1947) (producer)

5. Bedelia (1946) (producer)

6. The Voice Within (1945) (producer)

7. Hatter’s Castle (1942) (producer)

8. The Stars Look Down (1940) (producer) (as I. Goldsmith)

9. I Killed the Count (1939) (producer)

… aka Who Is Guilty? (USA)

10. The Lilac Domino (1937) (producer)

11. Southern Roses (1936) (producer) (as Isidore Goldschmidt)

12. Whom the Gods Love: The Original Story of Mozart and His Wife (1936) (co-producer)

… aka Mozart (USA)

… aka Whom the Gods Love (UK: short title)

Writer – filmography

1. The Scarf (1951) (story) (as I.G. Goldsmith)

… aka The Dungeon

2. Bedelia (1946)

One of the movies that caught my eye was The Scarf, which Isadore Goldsmith both produced and wrote the story it was based on. Was there some connection also to the book of the same title written by Robert Bloch (of Psycho fame)? No, not so. The co-author of the story, according to IMDB, was Edwin Rolfe, who has a single entry in CFIV himself:

ROLFE, EDWIN (1909-1954); Reporter, editor, foreign and war correspondent; poet; publicist for shows.

* * * The Glass Room (with Lester Fuller) (Rinehart, 1946, hc) [Los Angeles, CA] Low, 1948.

And The Scarf, by Robert Bloch (Dial, 1947) seems to have never been made into a movie at all.

As for Vera Caspary, she has many entries in CFIV (which I won’t repeat here), even more as a screenwriter in IMDB, and there is a full biography for her here.

She’ll certainly best be known as the author of Laura, however, and (more than likely) for the movie more than for the book.

But which of her stories did Frederick Goldsmith use to construct his novel Murder in Mayfair? At the moment I do not know, but if and when I do, you can be sure you will read about it here.

Sun 28 Jan 2007

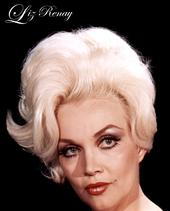

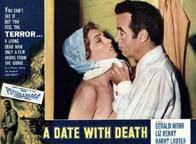

Born Pearl Elizabeth Dobbins on May 14, 1926, Liz Renay died January 22, 2007, at the age of 80 in Las Vegas, Nevada, of cardiopulmonary arrest.

Quoting liberally from her biography at www.imdb.com, it is clear that there is no immediate connection between Ms. Renay and crime fiction:

“Liz Renay’s extraordinary life could almost be a movie script. Raised by fanatical religious parents, she ran away from home to win a Marilyn Monroe lookalike contest, and become a showgirl during the war. She eventually became a gangster’s [Mickey Cohen’s] moll, and when he was arrested she refused to co-operate with the authorities and was sentenced to three years in Terminal Island prison, where she wrote her autobiography. On release she became a stripper, and self-publicist, performing the first mother and daughter strip and the first grandmother to streak down Hollywood Boulevard.”

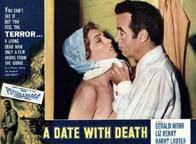

However, and a big one at that, Ms. Renay did appear in a few films that do warrant mention here, the first being an obscure classic of late 1950s film noir, Date with Death, 1959, starring Gerald Mohr.

A semi-anonymous reviewer on IMDB says great things about the movie, from which I have excerpted the following:

“This also is one of the few REAL lead dramatic roles I’ve ever seen Liz Renay in, and she is fantastic. She often was used in smaller roles for name value, but here she is the female lead, and she is seductive, charming, warm, and everything a b-crime-movie leading lady needs to be…. As for Gerald Mohr, I’ve always considered him one of the great hard-boiled leading men, both on radio (where he played Phillip Marlowe) and in film. Here he is both tough and sympathetic, yet initially mysterious. He brings much depth to a role that many would have just walked through. For the fan of low-budget 1950s crime films …

DATE WITH DEATH should be a must-see. With a fine jazz score, great location photography, an exciting plot, and some genuinely surprising twists and turns,

DATE WITH DEATH does not need any subliminal gimmicks to be a model b-crime film. I give it ten stars out of ten.”

Go here for the rest of Mr. Renay’s onscreen credits, which appear largely to be schlocky B-movies or (far) less, but which also include a part on the television series Adam-12, and a role as a stripper in Peeper (1975), based on Keith Laumer’s novel Deadfall, later titled Fat Chance, in which Michael Caine plays a London PI in LA by the name of Leslie C. Tucker. Natalie Wood plays the femme fatale.

Sat 27 Jan 2007

Here are the first few lines of the obituary article in yesterday’s New York Times for Daniel Stern:

Daniel Stern, who sifted through his careers in jazz and symphonic music, advertising, movies and academia for psychic grist for the bittersweet, tightly crafted novels and short stories that were his crowning achievement, died Wednesday in Houston. He was 79.

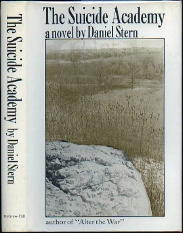

I’ll get back to the coverage of Mr. Stern’s overall career in a minute, but among his other accomplishments, there’s one that makes him stand out from every other cellist who played with Charlie ‘Bird’ Parker, and that’s the fact that he also has an entry [one book] in Allen J. Hubin’s Crime Fiction IV:

STERN, DANIEL (1928- )

* * *The Suicide Academy (McGraw, 1968, hc) Allen, 1969.

A blurb from the book itself says: “In The Suicide Academy Daniel Stern has taken a communal dream of our increasingly ordered times and turned it into a nightmare. Part spy story, part existential parable, this coldly brilliant novel makes for an unforgettable reading experience.”

About the book, the New York Times also goes on to say, and I quote:

The Suicide Academy (1968) imagines a world flecked with institutions where people can commit suicide. An administrator of one of them grapples with the morality of the government’s offer of more funds if suicides increase. Reviewing the book in

The Village Voice, Anaïs Nin cited Mr. Stern’s ability to “toss all the facts into space, to reverse their chronological monotony, upset established curriculums.”

From the descriptions so far – I haven’t read it, or I’d tell you more from a personal point of view – it appears to be a step beyond your usual book of crime and detection, if not two or three. To confirm this, here are some excerpts from a longer review, this one from Time magazine for September 20, 1968. It begins this way:

THE SUICIDE ACADEMY by Daniel Stern. 173 pages. McGraw-Hill. $5.95.

Outrageous subjects that were once shocking sources of satanic laughter now seem hardly ticklish at all. Black Comedians today tend to be admired like TV gagmen and nightclub acrobats – less for jolt than for sheer agility.

In that class, Daniel Stern, a critic-novelist (After the War, Miss America) long preoccupied with the dusty corners of the modern soul, proves a deft performer. His literary colleague Kurt Vonnegut recently toyed with industrialized suicide (Welcome to the Monkey House), but only as an example of the dehumanized modern world efficiently eliminating Malthusian excess. Stern’s Suicide Academy, by contrast, has a more promising metaphoric reach.

In Stern’s establishment, the clients come for one day only. With the aid of a scrupulously neutral staff, they are measured and examined. Between bouts of play and sleep, they study their own lives and the world, life wish and death wish together. Then comes calm choice — a return to the world or death, an end reached through a wide range of means provided by the management. Suicides, Stern observes, are the graduate students of the academy.

and it concludes:

The Suicide Academy is left as a palatial metaphor hardly explored and barely furnished. It is largely unpeopled, too, except for Wolf’s [the head of the Academy’s] assistant, a splendidly grotesque, wasp-tongued Negro named Gilliatt. Archly antiSemitic, he quotes upbeat Talmudic texts to needle Wolf, and continually accuses him of secretly sabotaging the academy’s sacred neutrality in favor of life. Gilliatt reasons that the Jews invented resurrection and so are rotten with humanitarian sympathy. Gilliatt may be the best bit-part player of the literary year.

Other accomplishments of Mr. Stern deserve a mention. Even though they’re outside the realm of crime fiction, they include:

● He was born on Jan. 18, 1928, and grew up on Manhattan’s Lower East Side and in the Bronx.

● He played the cello with Charlie Parker and the Indianapolis Symphony.

● He was a vice president at Warner Brothers Studios, CBS and the McCann-Erickson advertising firm.

● After nine novels, many of them well reviewed, Mr. Stern found his métier in the short story.

● At the time of his death, he was Cullen Distinguished Professor of English at the University of Houston.

● For Warner, he promoted the movie “Woodstock” with the line, “Nobody who was there will ever be the same. Be there.”

Sat 27 Jan 2007

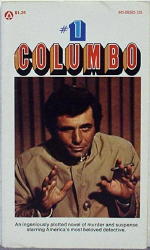

As promised in the update at the end of the previous post, here are the appearances of Lt. Columbo in print. Some of these are becoming difficult to find, even with the assistance of the Internet to help track them down. I wish I were able to show you covers of all of them, but it would be rather crowded if I did, or if I could. Some I don’t have copies of myself.

LT. COLUMBO in book form –

* RICHARD LEVINSON & WILLIAM LINK:

o Prescription: Murder. French, 1963, pb. [Three-act play.]

* ALFRED LAWRENCE:

o Columbo. Popular Library, pbo, 1972.

o The Dean’s Death. Popular Library, pbo, 1975.

* HENRY CLEMENT:

o Any Old Port in a Storm. Popular Library, pbo, 1975.

o By Dawn’s Early Light. Popular Library, pbo, 1975.

* LEE HAYS:

o A Deadly State of Mind. Popular Library, pbo, 1976.

o Murder by the Book. Popular Library, pbo, 1976.

* BILL MAGEE & CARL SCHENCK:

o Columbo and the Samurai Sword. Black, hc, 1980. Note: This is one of the very few First Editions published by the Detective Book Club [known for their three-in-one editions, of which this is one, or a third thereof] and as such is rather scarce and hard to find.

* WILLIAM HARRINGTON:

o Columbo: The Grassy Knoll. Forge, hc, 1993.

o Columbo: The Helter Skelter Murders. Forge, hc, 1994.

o Columbo: The Hoffa Connection. Forge, hc, 1995.

o Columbo: The Game Show Killer. Forge, hc, 1996.

o Columbo: The Glitter Murder. Forge, hc, 1997.

o Columbo: The Hoover Files. St. Martin’s, hc, 1998.

Acknowledgments go as almost always to Allen J. Hubin, Crime Fiction IV, as the primary source for most of this data.

I’ll also take this an opportunity to thank Mark Murphy one more time for pointing out where I could go on the web to keep finding more information about Lt. Columbo. In his most recent email to me, he added: “A guy named Mark Dawidziak wrote a book, The Columbo Phile, some years ago. It was quite authoritative. I’ve also found this link to an interview with him…”

He’s right. There are commercials in this on-the-air interview, but you can skip them, and it’s very much worth listening to.

To sum things up, I hope, without too many more updates, Columbo as a character has been around long enough, and he’s been popular enough, that there’s plenty of information out there on him, either in print or on the Internet. In these last couple of blog entries, I don’t imagine that I’ve added anything that’s really new about him, but hopefully I’ve presented what I’ve discovered in a straight-forward and useful fashion. I’ve also ironed out some of the contradictions popped up as I went along, and tried to set the record straight on a few statements I found that were either incomplete or simply not so.

Or to put it another way, I certainly learned a lot.

Fri 26 Jan 2007

Here is but another of the alleys that researching can take you, if you are not wary, and even if you are. While looking up The Dow Hour of Great Mysteries — see the previous post — I found a short piece from the NY Times that suggested that Prescription: Murder, the first appearance of Lt. Colombo, the rumpled police detective made so famous by Peter Falk, made its first appearance on the Dow Hour.

Not so, and I have Mark Murphy to thank for pointing me to a website that has the right stuff, or in other words, the correct information. Of course you can go there to read it for yourself, and in fact you should. I recommend it. But since I had it wrong in my previous post, it behooves me (I always wanted to say that) to at least set up the correct timetable of the events relating to Lt. Columbo in this one.

[Added 01-27-07] March 1960. According to Mark Dawidziak, writer of

The Columbo Phile (Mysterious Press): “the very first appearance of the character wasn’t in a short story [by Richard Levinson & William Link] called “May I Come In?” The end of that story is a knock at the door: it’s the police, and if the door had opened it would have been Lieutenant Columbo standing there.”

The story appeared in

Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine, but someone, an editor perhaps, changed the title to “Dear Corpus Delicti.”

May 29, 1960. A drama anthology called The Chevy Mystery Show began on NBC. Hosted by Walter Slezak, new scripts were dramatized every Sunday. There were no recurring characters or actors.

July 31, 1960. “Enough Rope,” was that evening’s presentation, an original story written by William Link and Richard Levinson, introducing to the world a police lieutenant named Columbo, played by a veteran character player named Bert Freed, who received “second-to-last billing in the opening credits.” He is not even included in the IMDB listings for that episode.

1962. “Prescription: Murder” the stage play opened, with veteran movie and stage actor Thomas Mitchell playing Lieutenant Columbo. This was Mitchell’s last role: “He died while the show was touring the United States and Canada, before it reached its Broadway premiere.”

It is not clear whether the play ever reached Broadway. Some sources I’ve seen so far say yes, others say no.

1968. Filmed in 1967, “Prescription: Murder” appeared as a made-for-TV movie, with Peter Falk in the starring role. It was intended to be a one-shot appearance for the character, but fate (and the character’s popularity) had a way of changing things.

NOTE: What the author of the website cited above does, and in great detail, is to compare the story lines for each these first three appearances of Lt. Columbo, essentially the same story with differences, and how the character was presented and developed.

March 1, 1971. The pilot for the Columbo TV series was aired: “Ransom for a Dead Man.”

September 15, 1971. Columbo began its regular TV slot as a rotating part of the NBC Mystery Movie, with the first episode entitled “Murder by the Book.” When that overall umbrella series ended, Colombo continued to appear in a series of made-for-TV movies on a irregular basis. “Columbo Likes the Nightlife” was telecast in 2003, a stretch of some 35 years since Columbo began his run back in 1968.

Peter Falk is now 80 years old. No one could possibly fill his shoes (or raincoat), so this may mark the end of Lt. Columbo on the small screen.

SIDEBAR: February 26, 1979, to March 19, 1980.

Kate Loves a Mystery, starring Kate Mulgrew as Mrs. Columbo, had a short season of 13 episodes. The gimmick didn’t work out, the folks over at the

Columbo lot disowned her, and by the end of the run, the leading character was named Callahan (and not even the wife of some other police detective named Columbo).

UPDATE [01-26-07] It’s later the same day, and I see that I’ve forgotten to list the books in which Lt. Columbo has appeared over the years, mostly as novelizations of various screenplays, I believe, although I could be wrong on that. It’s late, though, and I think it will wait for another day. (Tomorrow, I hope.)

Next Page »