July 2018

Monthly Archive

Tue 31 Jul 2018

BLUE, WHITE AND PERFECT. 20th Century Fox, 1942). Lloyd Nolan (Michael Shayne), Mary Beth Hughes, Helene Reynolds, George Reeves. Based on a serialized story by Borden Chase (Argosy, 18 Sept-23 Oct, 1937; reprinted in book form as Diamonds of Death [Hart, paperback, 1947] and reviewed here ). Director: Herbert I. Leeds.

Blue, White and Perfect is the fourth of seven Mike Shayne movies made by 20th Century Fox in the early 40s, all starring Lloyd Nolan as author Brett Halliday’s famed private eye, Michael Shayne. As far as I know, I’m the only one who doesn’t care for any of them, although certainly some are better than others.

This, I think, is one of the others, but the reason I don’t particularly like any of them is that Lloyd Nolan, with his brash New York accent — not to mention the comedy aspects of the films — comes nowhere near the image of Mike Shayne I have in my mind. If the films had been made with a totally different fictional character’s name to them, I might like them more.

The Mike Shayne stories in the books and magazine were at least medium-boiled. The Lloyd Nolan movies were comedies, as far as I’m concerned, with lots of humorous banter between the characters, with hints of actual detective work breaking out only every once in a while. In this one, facing an ultimatum from his steady girl friend (Mary Beth Hughes), Shayne gives up his job as PI and takes a job as a riveter at a defense plant. Secretly, of course, he’s hired as a security expert.

And wouldn’t you know it, his first day on the job and a sizable amount of industrial diamonds is stolen. The trail leads Shayne to several stores, business establishments and other locales all around Los Angeles, and I have to admit the story really does along in very fine fashion.

All of sudden, though, about halfway through, the scene shifts to one aboard ship, bringing in two brand new characters: a glamorous girl (Helene Reynolds) Shayne knows from before, and a shady-looking fellow named Juan Arturo O’Hara (George Reeves) whom Shayne decides to keep close eyes on.

And instead of zipping along, the story stops almost dead in its tracks, the action limited to only what take place in cramped hallways, decks and the stairs connecting them. Only the occasional shots (not) ringing out liven things up (a silencer is used). Nor are there any surprises detective story wise, either. I’ll give the first half a B, but the second half? No more than a D.

Mon 30 Jul 2018

REVIEWED BY JONATHAN LEWIS:

FLIGHT TO FURY. Filipinas Productions / Lippert Pictures, 1964. Dewey Martin, Fay Spain, Jack Nicholson, Joseph Estrada, Vic Diaz, Jacqueline Hellman. Screenwriters: Monte Hellman, Jack Nicholson, Fred Roos. Director: Monte Hellman.

Filmed in the Philippines back to back with Back Door to Hell (reviewed here ), Flight to Fury is a low budget crime film that, while nothing spectacular, has some interesting sequences and hints of genius to come. Directed by Monte Hellman, and with a screenplay written by Jack Nicholson, the movie has a fatalistic sensibility from start to finish. This is largely due to some terrific hardboiled dialogue and compelling performances by Nicholson as a cynical diamond thief, and Filipino actor Vic Diaz as a sleazy criminal who likewise has illicit gains on his mind.

Although it takes a while for the movie’s plot to come into sharp focus, Flight to Fury soon reveals itself to be a caper film. A ragtag group of individuals are enclosed together on a small aircraft. Each seems to be hiding a secret. Or secrets. When the plane goes down in a remote jungle, it becomes clear that the pilot was smuggling diamonds. Four of the survivors, all male apart from one woman who is more than willing to employ her seductive charms to get what she wants, are soon struggling for possession of the diamonds that the now deceased pilot had stashed in his luggage.

And if you think surviving a crash is bad, just wait until some guerrillas stumble upon the group and take them captive. What happens next is both predictable and rather downbeat, with an obligatory firefight between the group and their captors as well as a final Western-style showdown between two men for control of the diamonds.

In the end, what makes Flight to Fury worth a look is that it paints a stark picture of a fallen world in which no one wins, everyone loses, and there are no heroes.

Mon 30 Jul 2018

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[4] Comments

REVIEWED BY BARRY GARDNER:

JOE GORES – Menaced Assassin. Mysterious Press, hardcover, 1994; paperback, 1995.

Gores has been one of my longtime favorites, and I had heard good reports on this; but I thought his last, Dead Man, was so poor that I approached it with a few fortunately unjustified misgivings.

Will Dalton’s estranged wife discovers something on the company computer not quite right, tells Will, and is murdered. The method looks professional, so Lt. Dante Stagnaro of Organized Crime is called in. There are no clues, but then people on the periphery of the case start to die violently, and someone called “Raptor” begins to leave messages on Dante’s answering machine that claim credit for them. But are they mob killings, or is this a private vendetta?

Welcome back, Joe. I think this is the best novel Gores has written in a long time. It’s also a very difficult book to describe in a brief space, because of the intricate and quite different structure. There are flashbacks, and shifts of viewpoint, and a running lecture on evolution by one of the principals, and one is never quite sure who is doing what to whom.

But don’t let any of that scare you off. It’s a virtuoso performance for Gores, who never loses track of where he is or where he is going, and doesn’t allow you to, either. At least not the former — you may well wonder right up until the end where he’s going. There are more characters central to the story than is the norm, and Gores does justice to all of them, particularly to the voice he gives to Raptor. This is fine hardboiled fiction.

— Reprinted from Ah Sweet Mysteries #16, November 1994.

Sun 29 Jul 2018

MONEY AND THE WOMAN. Warner Brothers, 1940. Jeffrey Lynn, Brenda Marshall, John Litel, Lee Patrick, Henry O’Neill, Roger Pryor, Guinn ‘Big Boy’ Williams. Based on the story The Embezzler, by James M. Cain. (Avon, paperback, 1944.) Director: William K. Howard.

[When I first wrote this review, I began by apologizing that I did not which story it was by James M. Cain the movie was based on. Now with all knowledge available at the push of the Google button, I can at last tell you.] It’s all about a bank vice president who falls in love with the wife of a teller who’s also a serious embezzler.

The question is, is the woman an accomplice, or not? It’s just enough plot to keep you watching, and just enough mystery to make you feel good when you figure it out before the players in the movie do. The minor comedy bits are more annoying than not, based (certainly) on nothing in Cain.

— Reprinted and revised as noted from Movie.File.8, January 1990.

Sun 29 Jul 2018

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[3] Comments

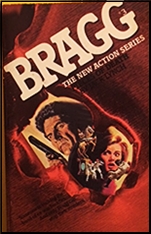

JACK LYNCH – Pieces of Death. Pete Bragg #3. Fawcett Gold Medal, paperback original; 1st printing, June 1982. Brash Books, softcover, 2014.

The cover, including both the illustration and the copy in white diagonally across the top, makes this book look like one of those men’s action series so popular around that time. Truth be told, while Pete Bragg is a private eye, there really is a little more emphasis on action and adventure than there is in most PI books — but not all that much. Men at the time looking for The Executioner or Penetrator type action would, I wager, have come away disappointed.

A fellow coming in by plane who Bragg had been hired to bodyguard is shot and killed, then so is the fellow who hired him, and Bragg decides to take it personally. It does not hurt that (as it so happens) that if he is able to help a group of WWII survivors, along with assorted wives and daughters, find a valuable relic they accidentally came across as their tour of duty in China was ending, his cut will be in the small five figures. But who’s on who’s side?

All in all, no more than an adequate PI story. Fun to read while reading, but there’s nothing that will stick in you mind when it’s over, other than the basic story line, and what they all are looking for. On the other hand, maybe that’s all you can hope for in a mid-grade B-movie caper such as this.

NOTE: There were a total of eight Peter Bragg books. You can find a complete list following my review of Seattle, #7 in the series, here.

Sat 28 Jul 2018

VALLEY OF [THE] EAGLES. General Film Distributors, UK, Lippert Pictures, US, 1952. Jack Warner, Nadia Gray, John McCallum, Anthony Dawson, Mary Laura Wood. Written by Nat A. Bronstein, Paul Tabori and Terrence Young. Directed by Terrence Young.

A film that left me goggle-eyed.

Valley starts off like a typical British “B†of the period, albeit set in Sweden. Well-acted, flatly shot, the first half hour or so deals with scientist John McCallum, whose MacGuffin gets stolen by his wife (a gorgeously cold Mary Laura Wood) and assistant Anthony Dawson. Swedish Police Detectives Jack Warner and Christopher Lee — looking like they just stepped across the street from Scotland Yard — plod into the case but McCallum is unimpressed with their efforts and investigates on his own.

So far so dull, but then Warner comes into his own, a more astute detective than we or McCallum thought. As their investigations converge, the scientist and the cop find themselves in friendly alliance as they follow the absconding couple north into Swedish Lapland.

At which point Valley of the Eagles switches gears splendidly. Stalled by a blizzard, Warner and McCallum keep up the chase by tagging along with a Lapp reindeer drive, and the film becomes a gripping tale of outdoor adventure.

A BIT OF BACKGROUND: Writer/director Terrence Young organized an expedition to Lapland and spent about eight weeks shooting near the Arctic Circle. It paid off, as he got stunning footage of reindeer herds stretching for miles, stampedes, wolves encircling the camp at night and pursuing the party by day, an incredible sequence with a remote tribe who hunt big game with eagles — just as falconers use their birds for smaller game — and a violent avalanche cascading down on fleeing villagers done without camera trickery.

Young achieves all this with an absolute minimum of back projection, and the result is staggering. Even these days, when you can do anything with CGI, the sight of all this actually happening on screen makes the heart race with excitement – or at least mine did anyway.

Amid all this, Director Young and the writers never lose sight of the characters. Detective Warner sees his criminal investigation turn into a matter of simple survival, while McCallum’s quest for his faithless wife and precious MacGuffin loses all meaning for him—a perfect confluence of acting and writing that adds real depth to the spectacle.

Valley of the Eagles is not an easy film to watch at times. It’s also hard to find. The only DVD I could get was in European format that can only be played on suitably equipped players here. But it’s more than worth the effort.

Fri 27 Jul 2018

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[10] Comments

REVIEWED BY DAVID VINEYARD:

HANK JANSON – The Accused. Hank Janson Crime Book #6. Telos Publishing Ltd., paperback reprint, 2004; also published in a Kindle format. Introduction by Steve Holland. Originally published by New Fiction, UK, paperback, 1952. (Hank Janson is a house name, in this case one used by Stephen D. Francis.)

I knew we were crazy. But I also knew nothing was going to stop it happening. It was inevitable, something that had to happen, like a car going downhill with no brakes and no means of stopping until it hit bottom.

Once upon a time when the Second World War had just ended and shortages of paper still hampered British publishing, a young man named Stephen D. Frances found himself with paper and a press and a contract for a twenty four page copybook, and no copy.

Taking a hand from writers like James Hadley Chase and Peter Cheyney he churned out a quick brutal tale of crime and sex set in the States and with a rough tough hero with an eye for a dame. He named the character Hank Janson (pronounced Yanson) and took the name as his pseudonym as well.

Over the years Janson made some changes, by the time the novels appeared he was a rough tough reporter for the Daily Chronicle (he sold ladies stockings in the first story) and he operated out of Des Moines (which British pulp expert Steve Holland has to remind British readers is pronounced de moyne). He remained tough, honorable, and as fascinated by the charms of female anatomy as Robert Leslie Bellem’s Dan Turner, if not as colorful in describing them.

Like Cheyney before him Janson’s ideas of American slang could be iffy at best, but also like Cheyney and Chase he was an original voice, if not always original in his ideas, full of energy and bright brittle bursts of violent images.

That imagery was what eventually got Frances and Janson in trouble with British obscenity laws. Seven of the Janson books were taken to court as obscene, and the one quoted most often by the prosecution is the little gem we have here, Accused.

Accused is one of the books published under the Janson byline, but not featuring Janson as a character. Instead the hero is a fellow named Farran who works in a diner for a fat obnoxious fellow named Friedman (His arms were thick and fleshy, his skin white and clammy, and his grimy, sweaty shirt gaped open down to his navel. His shirt was heavy with the smell of sweat and his face was damp and shiny, glistening with fresh perspiration a few seconds after he wiped the back of his arm across his forehead.) who has a younger beautiful wife he mistreats and keeps as a virtual sex slave … and yes, it is just as well this one wasn’t published here where James M. Cain might have objected to lifting the plot of The Postman Always Rings Twice whole cloth only with more heavy breathing.

We open with a graphic description of the most brutal third degree ever given in fiction as Farran recalls the events that lead up to him murdering Friedman in reveries between the beatings. Friedman’s wife, never given a name or much of a personality beyond victim and sex bomb, is the subject of no small amount of heavy breathing on the hero’s part.

She was dressed simply – very simply! It was a faded black dress, short-sleeved with a discreet vee of a neck-line in and tied at the waist by a belt that gave shape to the dress. The skirt was pleated and reached to just below her knees. She was barefooted, and her legs and feet were brown, kinda healthy-looking.

Even now, it was still hot in that kitchen. During the heat of the afternoon, it musta been an oven. And she hadn’t had time to cool off. Her face was shiny and damp, sweat patches blotched her armpits, and her youthful breasts seemed weary, sagged heavily against the damp bodice of the worn dress.

Farran lets us know in no uncertain terms Friedman keeps his wife a slave in nothing but that one dress (She was wearing the same black dress, and in the light of day I could see more clearly how thin and faded it was. I could see even more. It clung to her youthful contours faithfully, outlining her youthful breasts and the curves of her flanks with a faithfulness that was strangely stirring, almost as though she wore nothing beneath that dress.), no underwear, and noshoes, and more than hints, however obliquely, about what goes on behind the closed doors of the matrimonial bedroom door:

She was moaning. Giving little moans, punctuated with sharp gasps of pain. And it wasn’t what it could have been; a man and his wife roughing each other up a little. She was suffering, really suffering. The moans were breaking through her self-control as she steeled herself against pain.

I stood there in a cold sweat. It was Freidman who was with his wife. What could I do about it? He was a guy twice the size of me, and his wife hadn’t yet started screaming for help.

The real obscenity in the Janson books lies in what he implies but never actually says. The man had a real gift for innuendo in epic proportions. Over the course of about 50,000 words we get quite a bit of this kind of sweaty damp semi-masturbatory prose as Farran proceeds from victim of the brutal Freidman to his killer and eventually finds himself on trial for murder, his life on the line.

Certainly not obscene, that first paragraph is as far as anything goes, stopping well before the bedroom door. Ian Fleming and Mickey Spillane were writing much racier scenes when this was prosecuted, but this was sold as sleaze, replete with those brilliant Reginald Heade covers, and, well, it just felt obscene.

Steve Holland has also penned The Trials of Hank Janson about the obscenity trials and of equal interest, but Telos Press has brought these long lost classics of British pulp back into print in paperback and ebook form at low enough prices to indulge your taste for the long lost tales.

Frances wrote under several house names, and as Frances wrote the popular John Gail spy novels from the sixties and seventies, many published here; he also wrote as Dave Steel and Duke Linton, and God knows what else. Like most pulp writers he writes too fast and at times too sloppily, but the stories have great energy and at their best are fun once you get past the more painful attempts at American slang.

The best non-Janson entries, like this one, are no worse than the majority of male-oriented fiction of the type published in the States, and the better ones rise at least to the level of minor Gold Medal books in a similar vein (no few of them sailed a bit close to Cain as well).

The Janson books are usually better, if only because Frances set himself the task of keeping his hero more or less honorable, meaning the innuendo is much more controlled:

I was going to faint. The knowledge of it crept over me like a shroud of peacefulness. I was going to slip down into that soft, white mist and sleep for ever.

‘You fancied Freidman’s dame, didn’t you?’ he snarled.

I didn’t see him, but I sensed the gesture he made to the others, and as they moved in on me, I was smiling to myself, the white mist was gathering me up, gathering me into its embrace, cradling me, rocking me to sleep.

They couldn’t hurt me now.

Maybe it’s not authentic, but it’s pretty fair noir by any accounting, and for all the sleaze and innuendo it’s entertaining. It’s not that they don’t write them like this anymore, it’s just that they can’t replicate that paperback original voice of the era.

Thu 26 Jul 2018

M. S. KARL – Death Notice. Pete Brady #2. St. Martin’s Press, hardcover, 1990. No paperback edition.

The second case involving Pete Brady as a retired New Orleans crime reporter, now the editor of a small weekly newspaper in Louisiana — murder and arson just seem to follow some people, no matter where they go. I missed the first one, but this one’s a humdinger.

This one begins when a paroled killer is unaccountably allowed to return to the town in which the murder occurred. Doing nothing but sit on his front porch, he simply allows subsequent events to happen as they will, in ultra high intensity. This one really is a page turner.

Even better, it’s actually a detective story. There are clues, lots of them, and lots of false trails too. Lots of promise here. The only weakness, as far as I’m concerned, is that the basic setting is that of corrupt politics, crooked politicians and the money grubbing political bosses that back them. My first reaction was that of disbelief, that Karl was overdoing it by a factor of ten — but then again, just maybe not, considering that this is the country that also hatched Huey Long.

Under the name of M. K. Shuman (real name Malcolm Shuman), Karl writes another series of detective novels with PI Micah Dunn as the leading character. Dunn’s beat is New Orleans, and if this book is any indicator, that may be a series worth looking into as well.

— Rewritten and revised from Mystery*File #20, March 1990.

The Pete Brady series —

1. Killer’s Ink (1988)

2. Death Notice (1990)

3. Deerslayer (1991)

Thu 26 Jul 2018

Posted by Steve under

General[4] Comments

Yesterday was a traveling day. I’ve spent the last week plus visiting Jon in L.A. I left last week from CT just as a huge system of thunderstorms made its way up the East Coast, making shambles of airline schedules all along its path.

My plane was delayed two hours, and while I was sitting there, I chatted with an elderly couple also from CT on their way to Idaho to visit the woman’s sister. We finally took off, and naturally I never expected to see them again.

Coming back from L.A. today, and you already know where this going, right? Of course you do. My stopover on the way back to Hartford was in Minneapolis, and when I was delivered to the gate where the plane to CT was waiting, I looked up and sitting across from me was the same couple I was talking to just over a week earlier, now on their way back to CT from Idaho.

You couldn’t make up stuff like this and have anyone believe it if you tried.

Tue 24 Jul 2018

MRS. O’MALLEY AND MR. MALONE. MGM, 1950. Marjorie Main, James Whitmore, Ann Dvorak, Phyllis Kirk, Fred Clark, Dorothy Malone, Willard Waterman, Don Porter. Based on the story “Once Upon A Train, or The Loco Motive” by Craig Rice & Stuart Palmer. Director: Norman Taurog.

Somehow in the translation from printed page to film, Hildegarde Withers becomes Hattie O’Malley, a widow from Montana who wins $50,000 in a radio contest and heads to New York City to collect. Halfway there, Chicago to collect, her path crosses that of attorney J. J. Malone.

The rest of the movie takes place on the train, on the trail of a paroled embezzler. While James Whitmore plays the disreputable Malone to perfection, Marjorie Main simply tones down her Ma Kettle character a notch or two. It’s not much of a mystery, but funny? You bet!

— Reprinted and very slightly revised from Movie.File.8, January 1990.

Next Page »