Thu 2 May 2024

“Remembering The Great Merlini: An Interview with Clayton Rawson Jr.” by G. Connor Salter.

Posted by Steve under Interviews[7] Comments

An Interview with Clayton Rawson Jr.

by G. Connor Salter.

Clayton Rawson (1906-1971) was a key member of the American mystery fiction community for over four decades. His best-known work combined his interest in magic with mystery, particularly in stories about amateur detective The Great Merlini — a name Rawson used himself at magic shows.

His son, Clayton Rawson Jr., has carried on The Great Merlini legacy in various ways. In a March 2024 virtual event for Rendever Live, he showed some of his father’s magic tricks and observed that his siblings have said, “it’s like my father talking to them” when he performs. He has also shared samples of his father’s books and artwork, and shared memories in Something Is Going to Happen

I connected with Clayton in March 2024, asking about his father’s friendships with writers John Dickson Carr and William Lindsay Gresham. Our conversation developed into an interview, during which he shared well-known and obscure details about his exceptional father.

What can you tell us about your father’s early life?

Clayton Rawson grew up in Elyria, Ohio, and had a younger brother and two younger sisters. Magic was a passion from an early age but he also began to draw cartoons, and learned how to twirl a lariat. He produced some trick photographs that I have: juggling seven balls in the air, watching himself beat himself playing checkers, and a photo of him as a headless boy illusion.

One of his early magic tricks (some called it a prank) was to put a large barrel on top of the school’s flag pole. He didn’t tell me how he did it… I had to figure it out. He was disappointed that I didn’t do it at my high school.

The most detail about his life is covered in a biography that my brother, Hugh Rawson, wrote for one of the many reprints of our father’s mysteries: The Magical Mysteries of Don Diavolo, edited by Garyn Roberts, published by George Vanderburgh’s The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box in 2004.

When did he meet your mother?

My parents met at Ohio State University during the Roaring Twenties. We have a collection of letters he wrote to her and a series of letters that feature cartoons of cats. The story is about a forlorn cat hoping his cat sweetheart will write back more often.

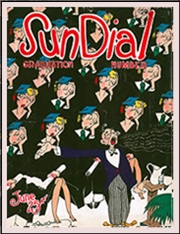

What was your father’s earliest published work that you can track down?

At OSU, he was the Editor-In-Chief of the Sun Dial, a college humor magazine. I have just in the past year been in contact with OSU and they were kind enough to scan and send a copy of his last Sun Dial — June 1928. He drew the cover and wrote a mystery story — the first mystery of his that we have — as well as a number of other articles and book reviews.

When did your father become interested in magic?

Hugh said it pretty well: “At about age twelve he saw an ad in The American Boy: ‘100 magic tricks for 10¢.’ He invested the dime and was never the same again.” (The Mysteries of Don Diavolo, p. vii.)

What were some of his accomplishments as a performing magician?

While he loved performing for friends and family and other magicians, he never performed on stage professionally. He invented many magic tricks and was a regular contributor to magic magazines and newsletters: The Phoenix, The Jinx, and Hugard’s Magic Monthly.

He co-produced The Society of American Magicians Annual Magic Show in 1965 and performed a version of his “Little Wonder Jim Dandy” routine … a trick involving eight volunteers and a Rube Goldberg style of sets, props, and a deck of playing cards.

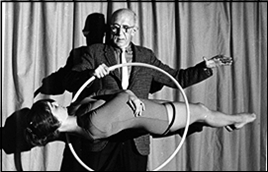

He first performed his floating lady levitation on the stage he built in our family’s backyard. It was revolutionary. He always wanted to perform it on Johnny Carson’s Tonight Show. In the 1960s, Orson Welles was Johnny’s permanent guest host. I never knew that my father knew Orson Welles and only found out when I answered the phone and took a message.

“Who is this?”

“Orson Welles…”

Orson had been a member of the Witchdoctors Club.

Orson could not get him on the Tonight Show, but a few years later, Walter Gibson got the floating lady booked on the Dick Cavett Show. But they didn’t need a magician or a floating lady, just the gimmick. Tony Curtis levitated Dick Cavett, and my father and I were behind the curtain making it happen.

What can you tell us about the Witchdoctor’s Club?

The best description of the Witch Doctors Club (or sometimes Witchdoctors Club) is in an article I contributed to about the group on the site Magicpedia: “Membership was by invitation only and the sole purpose was lunch.” And showing off sleight of-hand-tricks.

I only went to one of the lunches as they were in Manhattan on weekdays when I was in school. But I met most of the magicians at the summer picnics in Mamaroneck. I wish I had a list of the members of the Witchdoctors Club… as I wish I had more photos of them performing at the picnics.

What were some of his accomplishments as an illustrator?

He drew covers and cartoons for The Chicagoan, a magazine modeled after The New Yorker. He drew advertising art for newspapers. In 1930, he did a Christmas Cover for the Kiwanis Club Magazine Cover, which I later found on eBay. He illustrated a children’s book, The Little Brown Bear by Alice E Radford, published by Rand McNally & Company in 1938.

From 1930-1931, he drew more than a dozen two-page cartoons for College Life Magazine featuring a very risqué character named Dotty and her girl friends wearing skimpy clothes or nothing at all: “Dotty’s Diary,” “Dotty Joins the Swim Team,” “Dotty Goes to Hollywood,” and “Dotty Goes Nudist.”

In New York City, he drew illustrations for advertising in newspapers and magazines: Bordens, Kleenex, and many other clients. He also drew book jacket covers, notably for Agatha Christie’s Murder of the Calais Coach, which was later retitled Murder on the Orient Express.

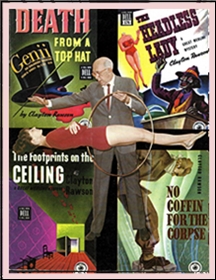

He drew the cover and the inside art for his first mystery novel, Death From a Top Hat. He also drew the crime scene maps for the Dell Map Back paperback editions of the four Merlini Mysteries. Very unusual for the author to be the artist, as well.

How did he begin writing mystery stories?

The Sun Dial has what may be his first mystery story — and, being in a humor magazine, it has a funny twist at the end. After a series of murders, each witness becomes a suspect but also becomes the next victim, and so on and so on until the final murder… the murderer is the author of the story, who decides it’s time to go to bed.

My father always loved mysteries. In the mid-1930s, he decided to write one and would read the fresh off-the-typewriter chapters to friends. For his third mystery, The Headless Lady, he joined the Russell Bros Circus and appeared as the Side Show Magician for about a week and a half.

He collected the ambiance, language, jargon, and slang of the circus for his book. We have another collection of his letters and postcards written to my mother and telling about life on the circus lot.

Death from a Top Hat introduced your father’s most famous character, The Great Merlini. Do we know if any particular characters or people inspired this character?

My father’s research of magicians and his own love of magic. As you will read in my brothers’ bio of our father, that’s very true: “In New York in the early 1930s, Rawson began to build a reputation for himself as an uncommonly original magician, one who invented new tricks and gave fresh twists to old ones” (p. vii).

My father’s short bio of The Great Merlini was published in The Jinx.

What can you tell us about his involvement with the Mystery Writers of America (MWA)?

He was a founder of the MWA and came up with their motto: “Crime doesn’t pay… enough.” He also suggested the name of the Club’s newsletter, “The Third Degree,” suggested they have an annual dinner at which the best mysteries of the year would be awarded an Edgar, a statuette of Poe.

In the early days of the MWA dinners, he wrote, produced, and acted in entertaining skits. He was awarded both an MWA Edgar and Raven for his contributions to the organization. His four Merlini Mysteries were published before the MWA was formed.

What was his involvement with Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine (EQMM)?

Over the years, he contributed 12 Merlini mystery short stories to EQMM. In 1968, he became the Managing Editor. My father was very familiar with most of the authors who contributed to EQMM. He knew Fred Dannay and Manny Lee, the authors of Ellery Queen stories, and was a close friend of Dannay.

He wrote most of his stories for EQMM in the 40s and 50s and his last, written to win a bet that he couldn’t write one, in 1971.

One interesting moments in Death from a Top Hat features The Great Merlini talking in detail about John Dickson Carr’s novel, The Three Coffins, where Dr. Gideon Fell gives a lecture on locked-room dilemmas. I understand that your father and Carr became friends when they lived near each other in Mamaroneck, New York. Can you tell us anything about that relationship?

My father first corresponded with Carr after Death From A Top Hat was published. Rawson and Carr began a “lock room mystery” competition, trying to out-mystify each other and their readers. The Carrs and the Rawsons had a long-time friendship, even with distance — the Carrs moved back and forth from Mamaroneck and London and Tangiers. Both my father and my mother enjoyed their company, and they were my godparents. My parents and the Carrs took short summer trips together twice with me as the chauffeur, to Fort Ticonderoga and Sturbridge Village, in the late 60s.

Both Clayton and John loved theatrics and produced skits for the MWA dinners. I remember stories of a Halloween party the Carrs had that included a “House of Horrors” in their attic.

Another interesting writing friendship is that your father and Carr were both friends with crime writer William Lindsay Gresham — another member of the Witchdoctors Club. Anything you can tell us about your father’s friendship with Gresham?

I’m not sure when my parents first met Bill, but it was before Joy Davidman left him for C.S. Lewis. I was too young to know her, but I do remember Renee and the two children she and Bill raised together, but I don’t remember much about them.

The next two photographs show Bill Gresham assisting my father as The Great Merlini in a levitating act with my sister Sarah.

When the Greshams would visit us in Mamaroneck, or I’d go with my parents to their apartment in New Rochelle, I was in my early teens and probably spent the time playing games with Rosemary and her brother, Bob. Nothing much sticks out except the time I missed Bill’s Fire Eating Act when he did it one summer evening on Merlini’s outdoor stage in the rain.

I also don’t have the disappearing bird cage that Bill left my father in his will. After my father died, my mother sold our house and had an open house sale of miscellaneous things. I had put the bird cage apart from the for-sale items but arrived late and somehow it was sold.

Who are some other writers he was friends with?

He knew Robert L. Fish and the others who founded the MWA. Every summer, the Mystery Writers were invited to a picnic in our backyard, on a different weekend than the Witchdoctors. Some of the magicians were members of both the Witchdoctors and the MWA.

In addition to the MWA crowd, one of my parents’ closest friends was Martin Gardner and his wife. He was the longtime contributor of the Mathematical Puzzle Column in Scientific American. My parents knew Martin when he was just starting out and working at Humpty Dumpty’s Magazine.

Another writer friend was Hartzell Spence. Hartzell was the co-author of Fred Bradney’s book about his life in the circus — The Big Top: My Forty Years with the Greatest Show on Earth — an autobiographical book Hartzel wrote that was made into a movie, One Foot In Heaven, and many other books and magazine articles. Hartzell also coined the phrase “pinup girl” when he was an editor for Yank, the Army Weekly in WWII.

For a number of years, my father was the mystery book editor for Simon and Schuster and got to know many more authors that way.

One interesting feature of your father’s first mystery novel, Death from a Top Hat, is that your father doesn’t just show magic tricks or characters discussing how those tricks are done; he has annotations referring to history books about magic. How deeply did he study the history of magic?

He was a collector of magic books and knew the history of magic very well. I remember hearing him talk with others, including Bill Gresham, about famous magicians and their acts. A longtime member of the Society of American Magicians, he had friendships with the biggest names in magic from the 1930s into the 60s, and many of them performed on our backyard stage. Dai Vernon, John Mulholland, Harry Blackstone Jr., Milbourne Christopher, The Amazing Randi, Tony Slydini, Harry Lorayne, and plenty of others.

What are some nonfiction books he wrote about magic?

The Golden Book of Magic and How To Entertain Children With Magic You Can Do are the two instructional books he wrote. I had one copy of the Golden Book and had nieces who all wanted copies. When eBay came along, I was able to buy many copies and give them away to relatives and friends who had children. I probably gave away 50 copies.

He illustrated Al Bakers’ book Pet Secrets, and he was the co-author of books on gambling with magician and card manipulation expert John Scarne: Scarne on Dice and Scarne’s Complete Guide to Gambling.

Did your father write any work under pseudonyms?

He worked under two names. He wrote the four Merlini Mysteries between 1937 and 1941. Stuart Towne was his pseudonym for stories about Don Diavolo, the Scarlet Wizard, and Mr. Mystery. They appeared in pulp magazines, Red Star Mysteries and Detective Fiction. The Don Diavolo stories appeared in the early 1940s.

Any idea why he decided to write another series as Stuart Towne?

He used the pseudonym because he was under contract for the Merlini character and many too many ideas for just one magician/detective. The Don Diavolo stories were collected into one volume, Death Out Of Thin Air.

What would you say set your father’s approach to mystery stories apart from earlier writers?

My father said that detectives solving most mysteries depend on following up on clues a la Sherlock Holmes. But my father also knew that most criminals had probably read Sherlock Holmes and knew how he used deductive reasoning — finding clues that are left by the perpetrator.

The Great Merlini figured the criminals would leave false clues to confound the detectives. So, the Great Merlini used inductive reasoning — figuring how he would have committed the crime. Magic and Crime share one thing: deception. Merlini solves the locked room mysteries in this manner.

Is it true that your father sometimes used the Great Merlini as his stage name when he performed magic shows?

Yes, he was always introduced as The Great Merlini. And The Golden Book of Magic was credited as authored by The Great Merlini.

How did his writing career develop as he became a family man?

Most of his creative writing was done before I was born, and when the rest of his children were young. As we grew older, he had to get a “steady job” in publishing.

At The Unicorn Press, he edited a magazine for their Mystery Book of the Month Club. He was the Picture Editor for the Funk & Wagnalls Yearbook for many years, then the Mystery Book Editor for Simon and Schuster and the Managing Editor of EQMM. During this time, he worked with Scarne on the two books I mentioned earlier.

He also wrote the Complete Play Production Handbook with Carl and Dorthy Allensworth, neighbors of ours in Mamaroneck. The Allensworths were both involved in producing plays for our community. Carl Allensworth also wrote plays produced on Broadway.

As a mystery book editor at S&S and EQMM and his long membership of the MWA, he continued to have many mystery writer friends who attended the summer picnic in Mamaroneck.

On a more personal note, what was it like having a father who wrote for a living?

When I was growing up in the 60s, he was working as an art director and editor. This was the time when he wrote the two books on magic, the book with the Allensworths, and ghostwrote Scarne’s Complete Guide to Gambling.

There were times when my sisters and I were told not to bother him because he was writing. This was usually in the summer in the 50s and early 60s when he was working on the side porch before he had air conditioning in the attic, where he had his desk, typewriter, library, and magic equipment.

A most memorable event was when my father came down from the attic and said he was quitting and couldn’t complete Scarne’s Complete Guide to Games. He got stumped and frustrated fiddling out and writing rules for playing Ma Jong.

The last years of his life were not very good. He became, at times, extremely manic depressive, and it was seasonal. In the summer, he was full of energy and ideas. In the winter, he slept a lot and was not very happy. In 1969, he had a series of strokes and died a few years later.

My father accomplished a great deal as an author, illustrator, and editor. The one thing he always wanted to do was produce a Broadway musical. He came up with the idea for one and even had a friend write a scene and lyrics to a song, for a “Fu ManChusical.”

Have you or any of your siblings pursued writing as a career?

My brother Hugh began a long career as a writer with his first books, The Dictionary of Euphemisms and Other Double Talk and Wicked Words. He and his wife, Margaret Miner, wrote a series of books of collected quotations.

After graduating from NYU, I worked my way up in the film/video/TV business and had to keep up with the changes in technology… film to videotape to digital media. I was an editor, cameraman, writer, and producer of industrial films, TV pilots, and entertainment specials. My career developed after his death. He did see one of my first films but never gave me any advice on writing. He did tell my sister something that I’ve kept in mind: “Write like Hemingway.” Short sentences.

My last job before retiring was as Director of Development and Executive Producer of Non-Political Specials for Fox News Channel. I created, wrote, and supervised the production of 90 hours of news documentary specials… many marking the anniversaries of major events in American History. For example, the thirtieth anniversaries of Apollos 8, 11, 13, and 17. I also worked on specials about D-Day, Pearl Harbor, 911, JFK Assassination, Boston Marathon Bombing. When I got my first on-screen credit, I was able to say to my mother, “See, I was doing my homework.”

My sisters both had a variety of careers. Joanna was first a potter and then a real estate salesperson. Sarah was an assistant at Sanford University and then for an internet startup. She became a potter after retiring a few years ago. Both have children and grandchildren.

Any writings by your father that haven’t been collected?

The most complete collection was published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box in 2006. In three volumes, it includes the pulp magazine stories about Don Diavolo and Mr. Mystery (volume 1), and all of the Merlini novels and short stories (volumes two and three).

Any upcoming projects — books being reissued, new anthologies — you can tell us about?

Currently, annotated editions of the four Merlini Mysteries are in the works. Neil Tobin, a magician and mentalist, came up with the idea and sold it to Vanishing Inc. for publication. Neil and I are communicating about it: I’ve checked things for him and scanned images from the first editions of the books for him.

What are some places people can find more information about your father — a biography, videos, things like that?

The magazine Genii’s May 2001 issue featured him with a cover story and a wonderful article by Michael Canick about his life and career. That issue of Genii also reprinted articles my father wrote for the magazine many years previous.

— Copyright © 2024 by G. Connor Salter. The photo images above and the videos below have been used with the kind permission of Clayton Rawson, Jr.

Rawson has produced an image archive of his father’s artwork and books, The Great Merlini Scrapbook,

and a short video about his father’s Dotty illustrations.

Both videos are available on YouTube. His upcoming work will include discussing his father and magic on Jeff McBride’s Magic & Mystery School Monday Classroom

About the Interviewer: G. Connor Salter is a writer and editor living in Colorado. He has contributed over 1,300 articles to various publications, including Mythlore, The Tolkienist, and Fellowship & Fairydust.

May 6th, 2024 at 11:06 am

On Connor’s own blog, he mentions this piece, and adds links to a two-part interview he did with Douglas Greene reminiscing about John Dickson Carr:

https://gcsalter.wordpress.com/2024/05/06/a-deeper-dive-into-magic-and-mystery-interview-with-clayton-rawsons-son/

May 6th, 2024 at 11:11 am

On Connor’s own blog, he mentions this piece, and adds links to a two-part interview he did with Douglas Greene reminiscing about John Dickson Carr:

https://gcsalter.wordpress.com/2024/05/06/a-deeper-dive-into-magic-and-mystery-interview-with-clayton-rawsons-son/

May 6th, 2024 at 11:54 am

A great interview for Merlini fans.

May 6th, 2024 at 3:06 pm

I read all four in their Dell mapback editions when I was in my teens, one step up from reading the Hardy Boys. Mind expanding? Yes! I think it’s time for me to read them again.

May 23rd, 2024 at 8:34 am

I love the Clayton Rawson books.

Is there a larger jpeg–or maybe a poster version–of Clayton Rawson levitating a lady?

I love the photo of Clayton on the back of his book _How to Entertain Children With Magic You Can Do_.

Amado “Sonny” Narvaez

July 29th, 2024 at 10:37 pm

[…] Fellowship & Fairydust. His interview with mystery author Clayton Rawson’s son was published here earlier in […]

October 12th, 2024 at 6:32 am

[…] https://mysteryfile.com/blog/?p=87597 […]