Sat 28 Feb 2009

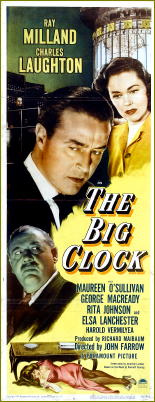

THE BIG CLOCK. Paramount, 1948. Ray Milland, Charles Laughton, Maureen O’Sullivan, George Macready, Rita Johnson, Elsa Lanchester, Harry Morgan, with uncredited appearances by Noel Neill and Ruth Roman. Screenplay: Jonathan Latimer, based on the novel by Kenneth Fearing. Director: John Farrow.

THE BIG CLOCK. Paramount, 1948. Ray Milland, Charles Laughton, Maureen O’Sullivan, George Macready, Rita Johnson, Elsa Lanchester, Harry Morgan, with uncredited appearances by Noel Neill and Ruth Roman. Screenplay: Jonathan Latimer, based on the novel by Kenneth Fearing. Director: John Farrow.

I’ve not read the book, or at least not so recently that I remember reading it, but from what I have been able to tell, the movie follows the text fairly closely — except for one thing. In the movie George Stroud, the highly successful editor of a true crime magazine, does not go to bed with the woman whose murder he finds himself framed for.

Otherwise the story apparently stays very much the same. The big kicker in both the book and the movie is that Stroud is put in charge of the ensuing investigation; that is, of finding the “killer,” himself, by his publisher, Earl Janoth, who in actuality — and in a sudden burst of abhorrence — really did commit the murder. The dead woman was Janoth’s mistress, and their relationship had been going sour for several weeks.

If I’m wrong about the book, let me know, but Jonathan Latimer’s screenplay can stand on its own, regardless. Ray Milland plays George Stroud, a very capable, self-assured fellow, but a very foolish guy in hanging around with Pauline York (Rita Johnson) when he has a wife (Maureen O’Sullivan) who is still waiting for a honeymoon after seven years of marriage.

Milland is very good as the man who finds himself more and more trapped in a web partly of his own making, as his own team of reporters continues to close in on him at Jaroth’s command.

Even better is Charles Laughton as that very same fastidious publisher, prig and interminably stuffy, a haughty person obsessed with time and efficiency and minimal cost, only to startle himself (momentarily) into becoming a normal person afraid of being caught at something he later can’t comprehend having done.

Maureen O’Sullivan doesn’t have a lot to do as Georgette Stroud, only to nag him (and rightfully so) and then stand beside him (at last) when he needs her most. Most viewers call this a classic noir film, and even if you haven’t seen it yourself, I hope my description of it will have you nodding your head and saying yes.

Occasionally disrupting the dark and desperate mood, though, are a few moments of comic relief, mostly (but not solely) at the hands of Elsa Lancester as a wacky, bohemian artist with a flat full of kids who can identify Stroud, but for (very good) reasons of her own, decides not to.

I certainly didn’t mind the comic interludes, but I wonder if purist noir aficionados do. The ending is a doubly happy one (I think), preceded by some very good detective work. Most entertaining, with emphasis on the “most.”

I watched this movie about several weeks ago, and I just watched it again before writing up these comments. I enjoyed it immensely both times, but there is a lot going on in this movie that I haven’t even begun to mention, and it takes more than one watching to appreciate it all.

I have it penciled in on my calendar to see it again in about a month from now.

PostScript: Ray Milland, Jonathan Latimer and director John Farrow teamed up at least one other time in Alias Nick Beal (1949), which I reviewed here last summer.

February 28th, 2009 at 1:52 pm

Latimer and Farrow teamed many times, notably for Night Has 1000 Eyes, Back To Eternity (remake of Farrow’s Five Came Back), and Unholy Wife (Farrow’s last film). Latimer wrote the screenplays for a number of good films including The Glass Key and one of the better B series entries, The Lone Wolf’s Spy Hunt (which featured Ida Lupino and Rita Hayworth in the cast). Later he penned quite a few episodes of Perry Mason as well.

The Big Clock is fairly close to the Kenneth Fearing novel. The gimmick of Fearing’s book, other than the idea of the suspect pursuing himself, was that the chapters were narrated by alternating characters — not always easy to pull off, but nicely handled in this case. Fearing’s other novel Dagger of the Mind is good too, and there is a science fiction one about a revolution that I vaguely recall as well.

The Big Clock is certainly noir, but as you say there is a lightness in tone in many scenes that may throw those who think of noir only as doom and gloom. And those used to Harry Morgan in his television incarnations may be surprised how effective he is as Laughton’s thuggish henchman (ironically in Appointment With Danger Morgan and Jack Webb play a team of sadistic hitmen). George Macready is also good as Laughton’s second in command. The book and the film were both intended in part as a take on the Time/Life news empire with Laughton’s character a shot at Luce.

The Big Clock was, of course, remade by Roger Donaldson as No Way Out with Kevin Costner and Gene Hackman, moving the action to the Pentagon and turning it into a spy caper, and remade again more recently with Denzel Washington. The idea of the hero hunting himself was also used in Derek Marlowe’s A Dandy in Aspic, and has become something of a cliche in recent years. I suppose in some ways it all dates back to Israel Zangwill’s The Big Bow Mystery (filmed with Sidney Greenstreet and Peter Lorre as The Verdict, the first film directed by Don Siegel)a pioneering locked room classic that touches on the theme, though it was also used by Maurice Leblanc in the best of the Arsene Lupin novels, 813. But Fearing seems to be the first to have used the idea for its potential as suspense. For that matter I suppose you could date it back to the father of detectives Eugene Vidoq who went from king of thieves to head of the Surete and is alleged to have planned, executed, and solved most of the crimes in Paris. Before that Henry Fielding has famed outlaw Jonathan Wild arresting innocent men for crimes he committed (Henry should know, his brother was blind magistrate Sir John Fielding, founder of the modern British police).

February 28th, 2009 at 2:18 pm

I saw both The Big Clock and Alias Nick Beal in glorious new prints earlier this month at the Noir City film festival. A bonus to watching the movies in this context is the additional information provided by host and programmer Eddie Muller, the czar of noir himself. Eddie observed that John Farrow had become a devout Catholic and insisted on several changes to the script, including that George Stroud not sleep with Pauline York. Farrow’s religious convictions would get free rein a year later in Nick Beal.

The other consensus from the Noir City screening is that The Big Clock is essentially a screwball comedy.

Come to think of it, I saw The Night Has A Thousand Eyes at Noir City last year. That festival is indispensable.

March 1st, 2009 at 10:35 am

No offense Vince, but if The Big Clock is screwball comedy then To Kill a Mockingbird is science fiction. Consensus or not, the few comic elements of The Big Clock hardly add up to the elements of classic screwball comedy. Even Elsa Lanchester’s eccentric painter is well within the usual noir pattern.

I know some people think noir is all doom and gloom and people moping about, but that is far from true of all the genre. There is nothing in The Big Clock that even approaches true screwball comedy, at the most it’s light relief. And it must be added that Farrow is one of the iconic noir directors who certainly was never known for or associated with comedy.

If you don’t think there is light relief in noir then I direct you to Murder My Sweet, The Dark Corner, The Big Steal, Double Indemnity,Strangers on a Train, and Uncle Harry. There is one screwball noir though, Hitchcock’s The Trouble With Harry. But just because a film has a laugh or two doesn’t make it a comedy anymore more than just being a black and white crime film makes it noir.

If anyone is seriously going to try to label The Big Clock as screwball comedy then the definition of both noir and the screwball school will have to be seriously redefined. If the “king of noir” wants to try and claim The Big Clock is a screwball comedy he’s going to find himself deposed pretty quickly since it is one of the icons of the genre. Revisionist history or not, noir films are not always the gloomy exersizes in crime they are painted to be. His Kind of Woman is unquestionably noir, but Vincent Price’s ham actor would be at home in a Marx Brothers picture. It’s A Wonderful Life is a comedy drama with elements of fantasy, but it has noirish elements. At some point the directors intentions have to be taken into account. Farrow wasn’t making a screwball comedy and Capra wasn’t making a noir. Farrow was just taking advantage of the stars at hand, all able performers with dramatic and comedic skills. By this definition the clowning around in Lives of A Bengal Lancer and Gunga Din make them screwball comedy and not British Raj adventures. They aren’t even though stars Gary Cooper, Franchot Tone, Cary Grant, and Doug Fairbanks Jr. all did screwball comedy. There’s comic relief in Hamlet, but it’s still a tragedy.

Roy Rogers films have big production numbers and one even has a title from a Cole Porter song (Don’t Fence Me In), but like it or not they are westerns, not Fred and Ginger in cowboy boots (despite what some fans think). At this rate some of Roger Moore’s James Bond films are screwball comedy (no comment).

That said there are plenty of screwball comedies with mystery plots — The Thin Man, The Mad Miss Manton, The Princess Comes Across, Woody Van Dyke’s underrated It’s a Wonderful World (often confused with It’s a Wonderful Life since both star James Stewart), and The Ghost Breakers.

I stick by my point about noir and screwball comedy though. The bodies are knee deep in Arsenic and Old Lace and it isn’t noir and His Kind of Woman plays much like a romantic comedy in many ways and it is noir.

March 1st, 2009 at 3:46 pm

No, I don’t see THE BIG CLOCK as a screwball comedy, either. While there are elements of the genre present, I’d still tend to call the funnier aspects “comic relief,” as I did in my original review.

Since it just played at the Seattle Noir Festival, I don’t imagine there’s any real reason to doubt THE BIG CLOCK’s credentials as a noir film, even by purists.

But it’s we, the current day viewers, who try to put labels on things, and after the fact, it becomes difficult (but often fun) to do. As David says more eloquently than I, though, it’s the director’s intent that matters — using a little bit of this as well as a lot of that, along with a modicum of input from whoever who the screenplay — and whatever comes out is the result of the best they could do at the time.

Vince, by the way, is Vince Keenan, and I think everyone reading this will enjoy his blog, which I’ve followed for a long as he’s been doing it.

You can catch all of his comments on the recent films shown at Noir City by following this link.

Where I just saw this. Vince, I hope you don’t mind, but I’m going to quote you personally on THE BIG CLOCK, rather than what you reported on as a Noir City “consensus”:

“The Big Clock’s metabolism is so fast that the movie practically fizzes. It’s got the crackle and snap of a screwball comedy, with a third act that knows how to tighten the screws.”

I can’t see anything to disagree with there. My judgment right now? It’s a big jump from a movie having the crackle and snap of a screwball comedy to one that IS one.

— Steve

March 4th, 2009 at 11:33 am

I’ll have to agree that I don’t consider THE BIG CLOCK a screwball comedy and I love screwball comedies(maybe to offset my love for dark, haunted, film noirs?). Of course Charles Laughton I find fun to watch even when he is not being funny. One of the great actors.

I’m pretty sure that THE BIG CLOCK gets some screwball elements from Jonathan Latimer, who did the screenplay. Latimer was a master of the hardboiled comedy as shown in his series of crime novels starring the hard drinking, wise cracking, private eye, Bill Crane.

Film noir is such a complex subject and certainly such films can contain screwball scenes and moments. Because if we stand apart from human life and view our activities and history with some degree of objectivity, we have to either laugh or cry. And it’s better to view things with a sense of humor sometimes.

March 5th, 2009 at 9:54 am

In Film Noir by Alain Silver and Elizabeth Ward (Overlook Press, 1979) they say of The Big Clock, it is “the lightest of all films that can be considered noir,”” which pretty much sums up the argument. The Appendices include short article on gangster films, westerns, period films, and comedies that have noir elements, but ultimately don’t include them in the mix. I think where we may make a mistake is in the difference between what is noir and what is merely noirish or has noir elements.

March 5th, 2009 at 10:25 am

That reminds me of a story I once heard.

There was a guy hired by an apple orchard to sort all the green apples from the red ones. He quit after working only one day.

Asked why, he said:

“The green apples are OK, and so are the red ones.

“It’s all the ones in between that drive me nuts.”

September 27th, 2010 at 2:52 pm

[…] also appeared in Ministry of Fear (1944), The Big Clock (1948), Alias Nick Beal (1949), Dial M for Murder (1954), The Safecracker (1958), Markham (a TV […]