Fri 1 Oct 2021

Mike Nevins on Mystery Writer ROBERT FINNEGAN.

Posted by Steve under Authors , Columns , Reviews[10] Comments

by Francis M. Nevins

Except for Hammett and Howard Fast I don’t believe I’ve ever written about a writer who was a member of the Communist party. Unlike Hammett and Fast, the subject of this month’s column escaped the HUAC-McCarthy purge, and possible jail time, but only by dying young. His legacy includes a huge pile of non-fiction issued by various labor organizations and the Communist-run International Publishers and, perhaps more relevant to readers of this column, three crime novels.

For those interested in his life, the place to begin is Harry Carlisle’s introduction to our subject’s posthumously published journalism collection On the Drumhead (1948), which has been digitized and is accessible online. Paul William Ryan was born in San Francisco on 6 July 1906 to Irish-American parents who apparently were not well fixed. “My family kept alive by running rooming houses,” he said near the end of his brief life.

He left school at age 15 to enter the work force, initially, so he claimed, as manager of a pool hall. In his twenties and thirties he held down a variety of jobs on ships, in bookstores and elsewhere, but his main occupation was journalism. Under the byline of Mike Quin he wrote an estimated million words a year for all sorts of labor union periodicals and for newspapers like the Daily People’s World, a West Coast paper run by the Communist Party. After the USSR signed a non-aggression treaty with Hitler, who a few months later attacked Great Britain and other countries, he formed a committee to agitate for keeping the U.S. from joining the war on the Brits’ side, a committee that quickly dissolved after Hitler broke his treaty and invaded the Soviet Union.

In 1944 he married the former Mary King O’Donnell and the couple soon had a daughter whom they named Colin Michaela. Shortly after the end of World War II, under the new byline of Robert Finnegan, he turned out three well-received whodunits starring newsman Dan Banion. The series abruptly ended with his death.

There’s nothing overtly Communist in the Banion novels but, like many a 1940s movie, they tend to paint the have-not characters in virtuous colors and the haves as, pardon the expression, toads. The style is readable but, like Hammett’s, unadorned, with the vivid figures of speech we associate with Chandler noticeably absent. If the trilogy had made it to Hollywood, perhaps the ideal star to have played Banion would have been John Garfield, and any number of actors who were blacklisted in the Fifties would have fit well in other parts.

From early on there are hints that the first of the trio, The Lying Ladies (1946), takes place not shortly after World War II, as its publication date would suggest, but rather back in the Depression-wracked and socially conscious 1930s. When later in the novel some of the characters listen to a radio broadcast announcing the “peace in our time” agreement between Hitler and Britain’s prime minister Neville Chamberlain, we know that the precise time is late September 1938.

The geographic setting is somewhere in the undifferentiated Midwest — Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, take your pick. We open as a penniless young tramp with a bent for poetry approaches a prosperous-looking suburban house in search of a meal, is invited inside by a vicious-looking woman and, after being fed, is asked to move some furniture in an upstairs bedroom where he’s promptly conked on the head. He wakes up the next morning in a farmer’s pasture, minus his cap, liquor-soaked and with money, jewelry and a bloody clasp knife in his pockets.

It’s no surprise when he’s quickly arrested for the murder of the housemaid who was found stabbed to death in the bedroom in which he claims he was knocked out. From the viewpoint of the reactionary local papers it’s a perfect case to attack soft-on-bums policies. Banion, a reporter in the area’s big city, is sent out to exploit the situation politically but, being a man of good will and friend to those who have no friend, he quickly becomes convinced that the young vagrant has been framed.

The jailed youth’s description of the woman who fed him leads to the madam of the local brothel, which survives by paying off the proper officials, and to a hooker with a heart of gold who sets out with Banion and a compassionate farmer (who could easily have been one of John Steinbeck’s Okies) to clear the young man. Besides the stripped-down prose there’s another feature that recalls Hammett, namely the Thin Man-style sex banter, in which Banion engages not only with his lovely wife Ethel but with just about every attractive woman he meets during the case.

Anthony Boucher in the San Francisco Chronicle (31 March 1946) called Finnegan’s debut a “[l]ong full-bodied story, rich in well-sketched characters and vigorous action,” and described Banion as “having a sense of social responsibility unique in the field.”

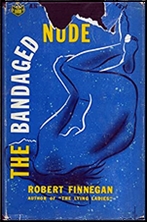

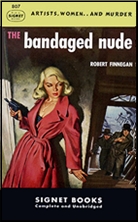

The Bandaged Nude (1946) was published in the same year as The Lying Ladies but was obviously written not long before publication, as witness its setting in post-WWII San Francisco with its housing shortage, rampant inflation and, most striking of all, a specifically postwar malaise, expressed in several ways including some poems written by various characters. Banion has seen combat but Ethel has died while he was in the army and, even though he’s gotten a job as reporter on one of the city’s papers, like so many protagonists of noir novels and movies he’s at an existential loose end.

One morning, while happening to drop in at the Hall of Justice, he’s invited to take a look at a recently discovered dead man, found with a weird green stain on his lips in a crate of ruined spaghetti about to be incinerated. He recognizes the body as that of a young vet and former artist with the Harry Stephen Keelerish name of Kenton Kipper whom he’d encountered in a saloon the previous night, trying to find out what had happened to one of his works, the nude painting of the title, which used to hang over the bar.

For no good reason — or as Tony Boucher described it, “prompted…by an odd sense of human fellowship” — Banion doesn’t identify the dead man but sets out on his own to avenge him. That green stain on his lips is soon discovered to come from a rare poison called leumatine which, turning up no hits on Google, I assume Finnegan concocted ex nihilo. Banion quickly learns that not just the nude but every one of the paintings Kipper sold before going into the army have been bought by a mysterious character who goes by a different name for each transaction.

Easing himself into San Francisco’s rather bohemian arts community, Banion interacts with a number of characters in Kipper’s life including his ex-wife (a Film Noir Woman of the first water), her estranged second husband, an obese homosexual art dealer and a sleazy PI. Eventually there are two more leumatine murders, one of them in Banion’s presence, and he himself narrowly misses becoming a fourth victim.

Between poisonings comes a lot of pursuit through the city, so much so that readers from outside the Bay Area could have profited if a San Francisco street map had accompanied the book. About two-thirds of the way through the novel one may begin to suspect who’s guilty, but few will stop reading until after the climactic fistfight between that person and Banion. Finnegan, said Boucher in his review, “has something affirmative and warming to say about people, and he says it here even better than before….”

That review was published in the Chronicle for 30 March 1947. In May of that year Finnegan was diagnosed with cancer and told he had two months to live. The doctors were not far off: he died on 14 August, age 41. His third and final novel was published the following year.

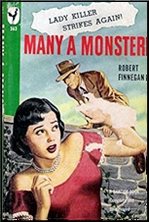

By far the bloodiest of the trilogy, Many a Monster (1948) has been described as one of the first serial-killer novels, although I disagree with the label because all the murders turn out to be connected. We open with the escape of a disturbed WWII vet on his way to an institution for the criminally insane after being convicted of the murder and dismemberment of three young women. (I know he couldn’t have been going to such an institution unless he’d been found not guilty by reason of insanity, but Finnegan is not a lawyer.)

Banion is assigned by his city editor to check out all the people closest to the fugitive: his sister, his ex-wife, his present girlfriend, a Marine buddy, and others. After the brutal murder of the sister he begins to question the escapee’s guilt. His doubts lead him to quit his job, but he carries on as the murders continue, even after a white supremacist gang captures and beats him and comes close to ripping out his fingernails with pliers.

The solution is surprising but is pulled out of a hat, as it were, and leaves a few key questions unanswered. With a total of fifteen fatalities — four before Page 1, another quartet during the course of the novel and seven neo-Nazis gunned down by Banion himself, who also disposes of their Fuhrer in a brutal fistfight — one might almost think our author was setting out to become the left-wing Mickey Spillane if one didn’t know that the first Mike Hammer novel, I, the Jury (1947), came out only shortly before Finnegan’s death.

His death, wrote Boucher in the Chronicle, “meant the loss to the mystery field of one of its most up-and-coming new practitioners…. [M]ay he rest in peace.” (31 August 1947).

It’s tempting to speculate on what would have happened to Finnegan had he lived to, say, the biblical three score years and ten. Would he have been imprisoned like Hammett and Fast? Impossible to say. Would he have quit writing as Hammett had done long before he was locked up? Most unlikely. Like Fast, would he have turned out twenty-odd mystery novels in his late years? Perhaps. If so, he might easily have earned for himself a few sentences or a paragraph in the history of our genre instead of a footnote. But a rich and fascinating footnote, yes?

October 1st, 2021 at 8:52 pm

Hammett mostly got nailed through his association with the movies and because he (rightly) refused to rat on anyone in the Soviet style Show Trials of HUAC.

Finnegan would likely have gotten by unnoticed. The guys pushing the Red Scare pretty much didn’t read anything more complex than comic books and even Steinbeck got by pretty easily with GRAPES OF WRATH not even going out of print that I know of.

Most of those who suffered were in movies, radio, and television. Just writing books pretty much got a pass as low hanging fruit with no real publicity for nailing a mere novelist much less a mystery novelist.

Hammett the Hollywood celebrity writer is what nailed him as well as the fact he was pretty outspoken in his support of the Party long after the worst was known about Stalin.

The books do sound like a Leftist Spillane a bit here, not really that odd, a lot of writers were starting to hit those same notes post War, Spillane just was at the right place at the right time with the perfect voice and a raw energy no one has matched before or since.

October 1st, 2021 at 11:30 pm

Thanks Mike for this article. I have all three of the novels and maybe now I’ll get around to reading them.

What bothers me about Hammett is that he served in the US army during both world wars. He was in WW I and WW II. To give him a prison sentence after this service to his country is shameful.

October 1st, 2021 at 11:42 pm

Hammett was a patriot, all of the others were not, and it was too tough at the moment to sort it all out. That took time. They did what they could and some of it was, if not wrong, then wrongheaded. That also took time.

October 2nd, 2021 at 10:23 am

Why I Hate Politics:

I should just say “All of the above” and let it go at that.

A few days ago, I marked my 71st birthday.

I got to see the whole “political process” evolve into the current chaos, from my ’50s childhood, through the late ’60s craziness, into the name-calling/foot-stomping of subsequent decades, right up to the present-day poison-spitting – and I don’t see anything getting better any time soon.

How this affects my reading, as dealt with here:

I’m still looking for a good story, with characters, a situation or two, sharp dialog, twists and turns, that sort of thing …

Sermonettes get in the way, no matter which side they come from; the best writers (on all sides) know how to write around them.

Away from all that, I still vote pretty much the same way I always have, steering as clear of doctrinal extremes as I can.

Quoting Max Allan Collins:

“I wish that the Left Wing and the Right Wing would both flap their wings and fly the hell away.”

To which Mike the Lowbrow Crank adds: Now More Than Ever.

October 2nd, 2021 at 4:29 pm

I do my best to keep this blog politics free. On the other hand, politics is a part of every day life (some lives more than others), and mystery writers are not exempt. One does one’s best.

As to Robert Finnegan himself, I think he qualifies as a Forgotten Writer. Who outside of readers of this blog remembers him? Like Walker, I have the three books in paperback, almost since forever, but I’ve never read any of them. Maybe this column from Mike will be the impetus I need to give one a try. I’d like to think so.

October 2nd, 2021 at 8:53 pm

This isn’t the first time Robert Finnegan has been discussed here. Even I had something to say about him.

https://mysteryfile.com/blog/?p=21930

October 2nd, 2021 at 9:45 pm

I’d quite forgotten that old review, Jim — over 8 years ago — so that’s my excuse, but I shouldn’t have forgotten that followup research you did on Finnegan.

October 2nd, 2021 at 9:26 pm

I’d rate this as more history than politics considering it is all pretty mute in 2021.

Hammett was indeed a patriot and courageous, but also a Stalinist apologist long past when most American communists were comfortable being that. That is still no reason he should have faced jail when Charles Lindbergh was walking around free if you are comparing active political activity for enemies of the State, and neither man crossed the line beyond silly politics and naivety.

My politics is straight up injustice is wrong.

It was a weird time, and both sides had their questionable behaviors.

HUAC, whatever the very real threat of the Soviets, quickly turned into a witch hunt and mostly “caught” innocents or harmless individuals like Hammett who, whatever their politics, were pretty harmless compared to say the Mafia whose existence wasn’t even admitted. Hammett himself found a grim humor in how harmless his fellow cell mates were surprised some of them survived incarceration.

I’m not suggesting there was no Soviet threat or no Soviet agents, only that Dashiell Hammett was a threat to nothing and no one but his own liver, which was true of all those blacklisted “influencers.”

It was a pretty sorry lot of threats to the nation.

I was just saying comparatively no one was going to touch Finnegan for writing mystery novels. He might have found his name on a Red list, but I doubt it would have really harmed him. Anyway, Robert Finnegan was already a pseudonynm.

From the description of the books they don’t sound sufficiently leftist to have encountered much push back unless they reached the mega seller status of a Spillane. From what looks like the publication date of that Signet edition of his second book I don’t think anyone had noticed his politics other than those reviews by Boucher.

They sound well worth looking up though.

In any case the mystery genre has always seemed to have no problem embracing multiple political faces at the same time. That Gore Vidal and Mickey Spillane had the same paperback publisher for their mystery novels is a pretty good example of that. Back in the day Conservative John Buchan had his hero Ned Leithen helped by a Labor Party Unionist in 1910’s serial THE POWER HOUSE. Peter Cheyney was briefly the secretary to Oswald Moseley but wrote thousands of words about tough heroes battling Fascist agents in England during the war. John Kenneth Galbraith had nothing but praise for William F. Buckley’s Blackford Oakes thrillers.

My own taste in thrillers is apolitical for the most part. However much I may disagree with many writers politics first and foremost I care whether they spin a good yarn and don’t beat me over the head with their political agenda bludgeon. I don’t say I never get toes stepped on, only that they aren’t that sensitive and I never go in expecting them to be abused.

February 20th, 2023 at 5:29 am

Hello,

As the editor of Hard-Boiled Dicks which devoted its 15th issue to Robert Finnegan, I’m surprised to read that nobody is always interested in Finnegan’work. By the way, the speculations about what would be arrived to him during Maccarthysm, are somehow curious: nothing according to several correspondants, forgotting that Len Zinberg had been obliged to disappear in 1948, after having been the target of witch hunt before coming back under Ed Lacy alias. In France, there are always people for reading Finnegan and Lacy.

With my best regards,

Roger Martin (author of “Ed Lacy, un inconnu nommé Len Zinberg 2022).

February 20th, 2023 at 10:52 am

Good to hear from you, Roger. Finnegan is all but unknown here in the US, but I’m glad to know he’s still read in France. I’ll forward your comment on to Mike Nevins!