Sat 1 May 2021

Mike Nevins Reviews Three Lam & Cool Novels by A. A. FAIR.

Posted by Steve under Columns , Reviews[2] Comments

by Francis M. Nevins

After completing his first three novels as by A.A. Fair about the PI team of Bertha Cool and Donald Lam — actually his first four novels, with THE KNIFE SLIPPED remaining unpublished until more than forty years after his death — Erle Stanley Gardner felt the need to reconfigure his odd couple. This is why, between GOLD COMES IN BRICKS (1940) and the next book in the series, Bertha was hit simultaneously with the flu and pneumonia and spent quite a bit of time in a Salt Lake City sanitarium where she lost about 100 pounds, although at between 150 and 160 she’d hardly be mistaken for a sylph.

At the beginning of SPILL THE JACKPOT! (1941), which takes place and was apparently written shortly after the 1940 presidential election which gave FDR his third term, a not yet reconfigured Donald is about to take her home by plane, with a brief stopover in Las Vegas so that he can confer with the firm’s newest client. Ad agency owner Arthur Whitewell has retained Bertha’s outfit to locate the young woman his son Philip was about to marry, who vanished shortly before the wedding after receiving a mysterious letter from a woman in Vegas named Helen Framley.

Donald finds Helen’s apartment quickly enough but she isn’t home and he decides to kill a little time at a nearby casino. In something of a Keeler Koinkydink, the woman playing the slot machine next to him is, you guessed it, Helen — and both she and the tough guy on the other side of her have gimmicked their machines so that they produce one jackpot after another. An attendant on the watch for just such trickery accuses the two of them and Donald too.

The tough guy and Helen manage to escape, but Donald is knocked down and arrested. He clears himself by proving his identity and agrees not to sue the casino in return for some co-operation. The attendant who socked Donald, a punch-drunk ex-boxer who if there had been a movie based on this book would probably have been played by Mike Mazurki, takes a huge liking to the little guy and offers to teach him some tricks of the pugilism trade, an offer which, as we’ll see, opens the door to Donald’s reconfiguration.

That evening Donald boards the night train to Los Angeles, but in the wee hours he’s hauled out of his sleeping compartment by the police and taken back forcibly to Las Vegas where Helen’s accomplice has been found shot to death in her apartment. Donald was at the railroad station at the time, waiting for his train, but can’t prove it, and soon he and Helen and the ex-pug go on the run.

The plot this time is less involuted than most of Gardner’s, and suffers here and there from careless plotting; Donald, for example, locates the vanished bride-to-be only because she’s going by a name no rational person in her position would have used. Without slowing the pace, Gardner punctuates the novel with side excursions, in the first of which we learn perhaps more than we want to know about the gimmicking of slot machines.

But the later excursions are much more rewarding. I especially liked the sequence where Donald and Helen and the ex-pug Louie Hazen, on the run from the police, camp out on the desert as their creator loved to do most of his life. “There has never been anything quite as soul-satisfying, quite as filled with the promise of life, as the smell of coffee out in the open when the fresh air has done its work and you realize that you’re ravenously hungry.â€

I also enjoyed the later scenes where the three hole up in a one-cabin wilderness motel — with how many bedrooms remains murky — and Louie teaches Donald to be a boxer. Gardner, you may remember, fought in a number of unlicensed matches in his salad days. At the climax Donald finds a confession letter from the murderer (who actually killed in self-defense), lets that person go free and frames one of the other characters who is much more of (forgive me, all you critters who bear the noble name of Bufo bufo) a toad, although the frame would fall flat on its kiester unless Donald and the dead guy happen to be of the same blood type. I challenge anyone to find an ending so cynical in a Perry Mason novel.

From its title you might guess that gambling would also figure prominently in DOUBLE OR QUITS (1941). But the first word in the title of the fifth (or, if you count THE KNIFE SLIPPED, the sixth) Cool & Lam exploit actually refers to that old standby of crime fiction, double indemnity — and to the legal difference between accidental death, which doesn’t pay double the face amount of a life insurance policy, and death by accidental means, which does.

On a fishing excursion Donald and Bertha meet a prosperous doctor who immediately hires the firm to investigate the theft of his wife’s jewels from a wall safe in his study to which he alone knew the combination — or so he thought — and the simultaneous disappearance of his wife’s secretary.

Donald spends that evening at the doctor’s house meeting his family, which includes a niece and nephew of the wife who are living with their aunt and uncle. Later the doctor goes out to make a couple of house calls, leaving Donald in his study. Close to midnight, during a Santa Ana windstorm, Donald finds him dead in his garage, apparently a victim of carbon monoxide poisoning while tinkering with his car, whose motor is running and whose glove compartment contains a valuable ring belonging to his wife plus the cases for all the stolen jewelry.

Unfortunately for the widow, who’s the beneficiary of his life insurance policy, if the situation is what it seems his death was accidental but not by accidental means. Result: no double indemnity.

The complications keep piling up along with suspicious characters like the vanished secretary’s roommate, the niece’s ex-husband and her lawyer, a sinister chauffeur and a suave oil speculator. Eventually Donald sets up a test in the garage, trying to establish that the Santa Ana winds might have slammed down the overhead door, which would constitute accidental means and require the insurance company to pay double.

But everything goes wrong and Donald winds up in a fistfight with the insurance adjuster in which, thanks to Louie Hazen’s training in SPILL THE JACKPOT!, he acquits himself handily. He also makes out very well in his employment situation, literally quitting the firm in mid-case until Bertha promotes him to full partner.

Back on the job he finds another body, this one clearly a murder victim, strangled with string from a girdle tightened around the neck by, I am not making this up, a potato masher. DOUBLE OR QUITS earned a rave from Barzun & Taylor in A CATALOGUE OF CRIME (2nd ed. 1989): “One of the best of the A.A. Fair stories. It is witty, reasonably simple, and brilliantly told….â€

Personally I found it no more witty or brilliantly narrated than any other book in the long-running series, with a plot not simple but all too complicated, characters with confusingly similar names (would you believe Timken, Timley and Harmley?), and at least one crucial fact — that the two doctors in the cast live within walking distance of each other — kept concealed from us until too late. But it’s readable enough and plays at least partially fair, so let’s give it one thumb up.

Between DOUBLE OR QUITS and the next C&L novel, Pearl Harbor was attacked, the U.S. went to war, and every mystery writer with a male series character below middle age had to face the question Why is my man not in uniform? Gardner didn’t have to worry about Perry Mason, whose age was never given and whom most readers probably thought of as in his forties, but with Donald Lam, who had been established as in his late twenties, it was a different story.

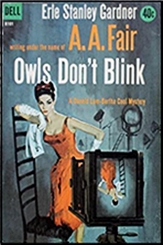

OWLS DON’T BLINK (1942), which takes place a few months after Pearl Harbor, opens in medias res and in the middle of the night with Donald in New Orleans trying to track down yet another vanished woman, whose apartment in the French Quarter he’s rented for a week.

In the morning Bertha arrives in town by train along with the firm’s latest client, a New York lawyer who had hired these Los Angeles PIs to find a vanished woman in New Orleans but refuses to explain why he wants to find her. Donald locates the woman easily enough but soon discovers that she was using another woman’s name

and winds up in the middle of a Machiavellian legal maneuver to invalidate a wealthy Californian’s divorce on the ground that it wasn’t his estranged wife but another woman who was served with process.

Then the lawyer who dreamed up the scheme is shot to death in the present apartment of the woman Donald was looking for, and the trail of the woman she was impersonating leads him first to Shreveport and then back to L.A.

The plot has a little bit of everything: scams within scams, gun switching, legal issues, a consignment of silk stockings that exists only in Donald’s imagination, ju-jitsu, and a love song to that classic New Orleans dish, oysters Rockefeller. “The shells are placed in rock salt. There’s a little touch of garlic and a special sauce….And then they’re baked, right in their shells.â€

It’s such a rich assortment of ingredients that few will object to the Keeler Koinkydink that everything hinges on the two women in the dead man’s life living across an apartment-house corridor from each other.

During the middle stretches Donald discovers that Bertha has surreptitiously started a second business and wangled a contract to build military housing, apparently to keep him from being drafted on the ground that he works in a defense industry, and angrily retaliates, after solving the case, by enlisting in the Navy.

That decision brings the first sequence of C&L adventures to an abrupt end. How Gardner managed to continue the series while his male hero was in Navy whites must be saved till later this year.

May 1st, 2021 at 7:43 pm

That desert sequence in SPILL really resonated with me, and is one of the best examples of just plain good writing in any of Gardner’s novels.

For fun I rate the Lam and Cool books as Gardner’s greatest creation. I still love Perry Mason, and the plotting and maneuvering are often better integrated in them, but Donald is such an ingratiating character, and while Bertha is no Nero Wolfe you get something of the feel of Archie and Wolfe from Donald and Bertha’s dealings.

Best of all by making Donald a “runt” Gardner couldn’t take any of the tough guy short cuts common to the genre. Donald, no matter how tight the corner, and he gets into some really tight ones, has to think his way out and always manages to do so keeping on his toes.

Because of the nature of the Lam and Cool books compared to Perry and company the books feel a bit more dated than the Mason novels which can almost be interchangeable after the first ten or so in terms of time period, but Donald in the end wins me over. He’s easily the most engaging character Gardner ever created and for me the most fun to read and reread.

May 1st, 2021 at 7:51 pm

I go back and forth between which I favor more, Mason or Cool/Lam. I think it depends on which way the wind in blowing on the day when I decide which one I will read (or re-read) next.

All for the same reasons you state, David, so there’s no need for me to repeat any of them.

But one thing you said I hadn’t realized before, and you’re right. The Mason books are interchangeable in terms of the year they take place, while the Fair books are dated simply because they are dated. When they take place is often a substantial part of the story. But does it bother me? No, not at all, and that’s why it never occurred to me before.