Return to

the Main Page.

MARTIN M. GOLDSMITH -

Detour: An Extraordinary Tale MARTIN M. GOLDSMITH -

Detour: An Extraordinary TaleO’Bryan House, Publishers; trade paperback, 2005. Hardcover edition: Macauley Co., 1939. The people behind O’Bryan House, and that includes Richard Doody who wrote the introduction, have done the fans of noir fiction a tremendous favor in reprinting this book. If you are thinking, “What book?” and I imagine many of you are, you are in exactly the same position I was when I first heard about it. Now of course there is The Movie Version, which perhaps you have heard of. If there ever were a poll of noir film fans, the film that is based on this book would have to rank in the top two or three of all time. Forgive me, though, if I don’t review the movie, although I will have to admit that it was the rhinoceros in my head when I was reading the book. I’ll review the book, though, if you so allow, and whatever movie you’re thinking of, I never heard of it. Let me get back to the “favor” that I mentioned in the first paragraph. There are two copies of the First Edition on ABE, neither of which has a dust jacket. The asking price for the first is $2500, and no, I did not loose the decimal point, so you can get up off your hands and knees and stop looking for it. The second copy is a mere $3500, but that one is signed by Mr. Goldsmith, who died in 1994, with a long inscription, so it is probably worth the money. There may be other ways to obtain the paperback edition, but one good way may be to order it from Amazon, and at an even more reasonable $14.95. If Mr. Doody has any alternative means to get a book into your hands, I will have him tell you later. To get started on the review, however, I hope that you don’t mind if I simply start off by quoting to you the first four paragraphs or so. Once again, if you are a fan of noir fiction, and if you were to tell me that you could put the book down after reading this, most of the first page, frankly, I wouldn’t believe you. One way or another, you’d be lying to me. Either you’re no fan of noir fiction, or you’re picking the book back up again when I’m not looking.

The big grey roadster streaked

by me and came to a halt fifty yards down the highway with screaming

tires. I got my lungs full of the smell of hot oil and burning

rubber. It choked me so that for a full minute I couldn’t

breathe. Neither could I move; I just stood there staring

stupidly at it and at the two black skid-marks the wheels left on the

concrete. I was heading west, via the thumb-route, and had been

waiting over three hours for a lift. I can’t remember exactly

where I was at the time, but it was somewhere in New Mexico, between

Las Cruces and Lordsburg.

It seemed kind of crazy, that car stopping. I had begun to believe that only old jalopies and trucks picked up hikers any more. Bums are generally pretty dirty and good cars have nice seats. Then, too, it was a lonesome stretch in there and plenty can happen on a lonesome stretch. The guy driving the car yelled at me over his shoulder. “Hey, you! Are you coming?” He acted as though he was in a great hurry, for he goosed his engine impatiently so I’d shake a leg. I snapped out of it. It was hot as a bastard and I guess the sun was getting me. Somewhere back along the line I had lost my hat and the top of my head seemed to be on fire. Anyway, the last two hours I had been waving at cars more or less mechanically, not expecting anyone to stop. A few hundred of them must have whizzed by without even slowing down a little to give me the once-over. You know, hitch-hiking isn’t as popular out west as it used to be. I suppose that is why the real bums stick to the rails. Telling this first part of the story is a down-on-his-luck jazz musician named Alex Roth. He is heading for California, and Hollywood in particular, since that is where his former live-in girl friend, Sue Harvey, has headed before him, only a week or ten days before they were to have gotten married. (She is the impulsive type, Alex tells the reader.) Picking him up in the grey roadster is Charles Haskell, who has a wad of money in his billfold and who is not long for this world. It is an accident, but Alex knows that no one will believe him, given that small incident (thirty days) in Dallas, and given that he and Haskell do look alike... Well, you get the picture. Backing up just a little, from page 32:

All right. Now you’ve

reached the part where all the mess begins. You’ll probably take

the rest of the story with a grain of salt or maybe just come right out

and call me seven different brands of liar. It sounds fishy – but

I can’t help that, any more than I could have helped what

happened. Up to then I did things my way; but from then on

something else stepped in and shunted me off to a different destination

than the one I had planned for myself. And there was nothing in

the world I could do to prevent it. The things I did were the

only things left open for me to do. I had to take and like

whatever came along.

For when I pulled open that door, Mr. Haskell fell and cracked his skull on the running-board. He went out like a light. In the meantime, Sue herself is not doing so well. From pages 47-48, she expresses to the reader her distinctly discouraged view of Hollywood, where she is getting by (barely) as a waitress, and not as the star she had thought she was destined to be. Or if so, not yet. It scarcely seemed believable, but only a

few months before I too had thought Hollywood a glamorous place.

I had arrived so thoroughly read-up on the misinformation of the fan

magazines that it took me a full week before I realized that the

“Mecca” was no more than a jerkwater suburb which publicity had sliced

from Los Angeles – a suburb peopled chiefly by out and out hicks (the

kind of dumbbells who think they are being wild and sophisticated if

they stay up all night) or by Minnesota farmers and Brooklyn smart

alecks who think they know it all. I soon saw that here were only

two classes of society: the suckers, like myself, who had come to take

the town; and the slickers who had come to take the suckers. Both

groups were plotters and schemers and both on the verge of starvation.

Goldsmith is less convincing as the voice of Sue Harvey than is as Alex Roth, but his portrayal of her is solidly etched in weariness and desire, and if one of the two of his two leading characters were to be considered hard-boiled, you have to know that it is not Alex. And returning to that half of the story, the reader’s brain will start to scream vicariously in warning when Alex, in turn, picks up a hitch-hiker, female, a woman named Vera, and man, does the story explode from there, eventually taking a leap with one staggering coincidence that exceeds even the often crazy incoherence of a Cornell Woolrich short story or novel, but in this kind of story, the stops are usually pulled all of the way out, and if they weren’t, you’d complain. Backing up one more time, from page 84, after Vera has agreed to the lift, saying as she gets in, “Los Angeles is good enough for me, mister.”

I kept looking at her out of

the corner of my eye for a long time, wondering who she was, why she

was going to Los Angeles and where she had come from in the first

place. I has asked her all of those questions when she first got

in the car, but her answers had all been vague. Her name was

Vera, though. I didn’t quite catch the last part. Vera’s

manner puzzled me in a way. She didn’t seem at all grateful for

the lift I was giving her. She acted as though it were only

natural, that it was coming to her. I had half-expected her to go

into ecstasies when I told her I was going all the way to the

coast. However, when I said I’d take her to Los Angeles, she

wasn’t at all surprised or pleased. She merely nodded her head

and shot me a look I couldn’t understand. It was a funny look,

shrewd and calculating, and a couple of times I turned my head and

caught it again. That gave me the notion that this dame was a

little simple upstairs.

These are the players. What you have just read includes considerably more quoting than I usually do, but there is little here, I guarantee you, that you will not glean from reading the few sentences of descriptive material on the back cover. There is plenty of story left, and on very nearly every one of the 158 pages in this book, there is another passage as quotable as any one of these. To my mind, this is the great undiscovered American novel, told from the underside, and somehow in its understated raciness, marvelously reminiscent of those rather notorious pre-Code days at the movies. Which brings us back around to one of my opening comments. They did make a movie out of this book, did you know?

January 2006

PostScript. In his introduction, Richard Doody mentions Goldsmith’s first book, Double Jeopardy (Macauley, 1938), but he doesn’t describe it at all, except to say that it is a crime novel. There are three copies on ABE, ranging in price asked from $175 to $275. That’s also beyond my price range, unfortunately, but (Richard?) I really would like to know more. Update. Richard has responded to the questions I asked, including how to obtain copies and to tell us what he knows about Goldsmith’s first book. You will find his reply in the Readers Forum. Second Update. Follow the link to a brief summary by Bill Pronzini of the author’s other two books. Bill also provides cover scans of all three in jacket.  CARA BLACK

- Murder in the Marais CARA BLACK

- Murder in the MaraisSoho Crime; trade paperback, October 2000. Hardcover edition: Soho Press, 1998. The publication date for the hardcover edition of this book is generally accepted to be 1998, but I’m a little puzzled by it. In the paperback edition I have, the copyright date is given as 1999. On the other hand, the book was an Anthony (and Macavity) nominee for Best First Mystery in 1999, so 1998 it has to be. (Until or unless I learn otherwise.) Since the obvious success of this, her first book, Cara Black (who is not the young tennis player from Zimbabwe, if you try Googling her) has written several more in the series, to whit: Murder in Belleville. Soho Press, 2000; trade paperback: April 2002. Murder in the Sentier. Soho Press, 2002; trade paperback: April 2003. Murder in the Bastille. Soho Press, 2003; trade paperback: April 2004. Murder in Clichy. Soho Press, 2005; trade paperback: March 2006. Murder in Montmarte. Soho Press, March 2006. All of these are cases of one species or another for Parisian private eye Aimée Leduc, a specialist in computer penetration, and her partner, René Friant, a “handsome dwarf with green eyes and a goatee.” Either the author or her character has struck quite a chord with her readers, as witness the almost yearly addition to the saga, and all in multiple printings. The books themselves are handsomely made as well, solid and somehow daring you not to pick them up. In Marais, the first of the six, Aimée is hired by an aged French Nazi-hunter to take a digitalized photo (converted from computer code) to an elderly woman still living in the Jewish section of Paris. Aimée arrives too late, finding Lili Stein murdered soon before her arrival; and her employer, Soli Hecht, is hospitalized soon thereafter in what is called a horrrific pedestrian accident. (We know better.) In France and apparently Paris in particular, life has gone on since World War II, but the days of Nazi control are never too far away from many inhabitants’ memories, both victims and collaborators. One such sad story is what Aimée finds herself up to her neck into. Aimée herself reminded me of Emma Peel and a not-so-voluptuous Honey West, mixed in with a dash of Sydney Bristow (of TV’s Alias) with her penchant for disguise and undercover work, slinking across Parisian rooftops in high-heeled pumps. And a form-fitting tight black skirt. (I can picture that.) Her partner René does not have much of a role in this one, content to opening password-locked computer accounts with an ease and nonchalance that makes it seem all too easy, with his one big scene consisting of being hung by his suspenders by one of the villains on a peg on the wall. It would seem churlish to suggest that passwords are not discovered as easily as they are in this book, but perhaps the author was just trying to keep the pace of the book moving, which is constant, fierce and filled with action upon demand. A large portion of Aimeé’s background is described in broad outlines, but some of her past is only hinted at. The part that is hidden may be part of what it is that has had readers coming back for more. That, and of course, the independent and free spirit that is Aimée herself, living as she wants, and being attracted to and sleeping with whomever she wants. Life in Paris is always an attraction to people in the United States, and whether her depiction is authentic or not, Cara Black makes the city come to life, the non-touristy part, made even more real by the inclusion of more than occasional phrases in French, in my mind just the right dosage. (Some of the reviewers of this book online have taken issue with the authenticity, which I noted but did not want to know about. If it was an illusion, I did not want the illusion broken. So I am pointing this out but stepping back, and with a double grain of salt, allowing you to be the judge.) I am therefore disappointed in myself for having to tell you my other impressions. The book is not meant for speed-reading. The prose, while not clumsy, is often as disjointed as the plot, jumping here and there and sticking in good scenes when a good scene is called for, whether it is always that particular scene or not. Here is one example of the author’s carelessness in the details. On page 217, the dying Soli Hecht’s last words are related as having been “Don’t ... let ... him ...,” then “Lo ... ” On page 251, the man’s last utterance, as Aimée is puzzling over the case to that point, she remembers as “Ka ... za.” Faulty details like this are deadly in a detective story, even if both versions could have been true. To my knowledge the point was never addressed, just another indication that in the world of detective fiction today, atmosphere and eye-catching characters can often carry the day, even if the puzzle of the plot is present but passed aside as if it doesn’t really matter. But here’s what is really funny, not in the sense of “ha-ha” funny, unless the joke is on me, but funny in the sense of “I can’t explain it either.” I enjoyed the book, and if you were to ask me if I am going to read another of Aimée’s adventures, the answer would definitely be yes. January

2006

COLIN ROBERTSON - A Lonely Place to Die Robert Hale (UK); hardcover, 1969. No US edition. You can sometimes buy the darnedest things on eBay, which is what happened not too long ago, when I picked up a small collection (seven) of Colin Robertson’s hardcover mysteries from a seller in Canada. And even though seven sounds like a sizable amount, it is indeed small when you compare it to the author’s total output, which runs to something like 57 novels and collections under his own name, not including a Sexton Blake adventure that came out under the house name of Desmond Reid.  The book I happened to pick, more or less at random out of the stack, is an adventure of Peter Gayleigh, a name I confess I did not know ahead of time, and whom I will get back to in a minute. First, though, here’s a list of all of the series characters that originated from the typewriter of Mr. Robertson. See how many of these fellows (and one gal, I believe) you recognize. In chronological order of their first appearances: Inspector John Martin (1935-39; three books.) Inspector Robert Strong (1935-40; four books) Victor Raiefield (1938-40; two books, both in tandem with Strong) Peter Gayleigh (1939-69; fifteen books) Edward North (1950-53; four books) Vicky McBain (1951-61; nine books) Supt. Bradley (1957-70; eleven books) Alan Steel (1965-68; three books) There were some stand-alone’s as well, in case you were trying to make the total come out right. And to tell you the truth, as I hinted at above, I am only assuming that Vicky McBain is female. Googling did not help. I found only one semi-useful reference, and it did not say either way, only that Vicky was a private investigator. And if you were wondering, no, none of the other six Robertson’s I obtained via eBay are Vicky McBain thrillers either, so there is no assistance gained from that quarter. But a few of the ones I have are affairs that it was up to James Bond knockoff Alan Steel to handle. I use the term “knockoff” deliberately and in similar fashion to Peter Gayleigh, who seems to have followed (gaily? sorry) in the footsteps of one Simon Templar, gentleman adventurer, rather closely. Or perhaps, if one to were to analyze the matter even more in depth, it might be possible to conclude that John Creasey’s Richard Rollinson (aka The Toff) was also a likely model. It is difficult, you see, to make generalizations when you’ve only read one or two books recently from any of the three authors, but I see in the notes I wrote to myself while reading the book in hand that at one point I was definitely reminded off The Toff, so I’ve changed my mind, and The Toff it is, at least for now. Well, I’ll give you the same paragraph I was reading when I made the quote, and you can judge for yourself. From page 62:

As Diana [Caryll,

Gayleigh’s close lady companion] had

found, he [Gayleigh] effected

the privileged few who worked for him in that way. There was

something in his vital personality that bound his subordinates to him

with enduring loyalties. It was partly the buccaneering

recklessness in those cool blue eyes; partly his inherent capacity for

overcoming any obstacle; but in the main that indefinable attribute of

the born leader.

On page 70, Gayleigh is referred to as “a notorious character, an insolent buccaneer,” so maybe the Simon Templar comparison is not so far off either, since that is exactly how I remember The Saint as being described in Mr. Charteris’s books. You decide. I had no idea while I was reading this book that it was to be Gayleigh’s last (recorded) adventure, a spy caper involving a deadly virus designed for germ warfare, although I doubt that it would have changed my opinion of it very greatly. He and Diana (see above) live apart, and they seem to have a rather chaste relationship, for all of the companionship there exists between them. What is rather remarkable – or let’s make that “who” – is a femme fatale who nearly comes between them. At the least, there are strong hints (see page 89) that Gayleigh is strongly attracted to Corinne Raeburn, a madcap heiress or jet-set socialite not akin to an early Paris Hilton, but with a gun. And she is also a woman who knows how to use it. The plot is strictly a paint-by-numbers sort of affair, brightly colored in spots and not making a lot of sense in others if you were to take the time to look at them up close. While the book kept me reading for the requisite amount of time, I see the other six books sitting there, and I say to myself, probably not next. Sometime soon, perhaps, but not next.

January 2006

J. P. HAILEY - The Anonymous Client Tor, paperback reprint; 1st printing, August 1993. Hardcover edition: Donald I. Fine, 1989. In the real world, the pseudonymous J. P. Hailey is known as Parnell Hall, as you may have already known o your own. Over the course of his writing career Hall has come up with three rather distinct series characters, two under his own name and one as by Hailey. First by a year was Stanley Hastings, who first appeared in Detective (Donald I. Fine, 1987) as by Hall. Hastings is an outwardly inept and reluctant private eye who does small-time jobs for ambulance-chasing attorneys. He is also still around, or so it seems, last appearing not so very long ago in Manslaughter (Carroll & Graf, 2003). Attorney Steve Winslow, to whom I’ll return in a moment, is the detective of record in the Hailey books, beginning the year after Hastings’ debut with The Baxter Trust (Donald I. Fine, 1988). He seems to have run out of cases to solve, though, since he hasn’t made an appearance in over 13 years now. Picking up the slack has been crossword puzzle constructor Cora Felton, who beginning with A Clue for the Puzzle Lady (Bantam, hc, 1999), again as by Hall, has proven to be very popular, solving a long line of detective novels that come out on a regular basis ever since. I’ve not (yet) read any of them, but the way the elderly Cora Felton has been described, she seems to be a deliberate reverse take-off of Agatha Christie’s Miss Marple: crusty, promiscuous, and a lush. (If I have that wrong, please let me know. I’d hate to be sued for defamation of character.) Let’s get back to J. P. Hailey, shall we? Here’s the list of the books in which Steve Winslow is the sleuth of distinction:  The Baxter Trust. Fine, 1988. Lynx, pb, 1989. The Anonymous Client. Fine, 1989. Tor, pb, 1993. The Underground Man. Fine, 1990. Forge, pb, 1994. The Naked Typist. Fine, 1990. No paperback edition. The Wrong Gun. Fine, 1992. No paperback edition. Something is entirely wrong here. If a book with a title like The Naked Typist can’t get reprinted in a paperback edition, something is wrong with the world of publishing, totally. In any case, after two hardcovers for which the softcover rights were not sold, that was it, no more, the end of the series. Now obviously after reading only the one book, and the second one in the series at that, I can’t possibly tell you what did go wrong. But will you allow me to guess? Ah, well no. On second thought, I won’t guess. Let me just tell you about the book I did read, and not the ones I didn’t, which is where the problem(s), if any – whatever they were – may actually be. Steve Winslow is a lawyer with only one client, a wealthy woman (heiress?) a carry-over from the previous book. I’m not sure how correct I’d be if you were to try to pin me down about the details, but I think I have the wealthy part right. As a result of whatever it was that happened in the previous book, Winslow is now Sheila Benton’s personal attorney. Although as a result he has a steady income, which is of course a good thing, he is also essentially only on call when needed. His secretary Tracy Garvin is so bored with nothing to do that at the beginning of this, the second book, she has just given him two weeks notice. She reads mysteries, you see, and working for Steve Winslow is nothing like what happens to Della Street in the Perry Mason books. Not until, that is, the morning mail brings an envelope containing ten thousand-dollar bills as a retainer from a client who deliberately has not signed the note that comes with it. It may be difficult to believe, but this creates a big problem. Winslow already has a client, and he cannot act on behalf of this new one in case there is a conflict of interest with the old one. He also cannot return the money, because he does not know to whom to give it back. Luckily Winslow knows a private detective whose offices are in the same building, an old buddy named Mark Taylor, and if he doesn’t remind you of Paul Drake, you certainly don’t get out and read those old Erle Stanley Gardner books very often, do you? Many complications ensue, and I won’t go into all of them – or any of them, for that matter – but if you were thinking that there’s got to be some really unusual courtroom shenanigans that occur, then you are thinking along exactly the same line that you should be. Here is a lengthy quote that I liked, lifted from page 129. It is in one of the aforementioned courtroom scenes, and Winslow is on the stand. (I wonder if Perry ever was, in one of his books – on the stand, I mean.)

“Mr. Winslow, I hand you a

piece of paper and ask

you if you have ever seen it before.”

“Yes I have.” “What do you recognize it to be?” “It is the list of serial numbers off of ten one thousand dollar bills.” “Where did you get that list?” “You just handed it to me.” And later on, from page 228:

As [prosecutor] Dirkson began citing cases into the

record, [co-defense attorney] Fitzpatrick

turned to Steve

Winslow. “We’re going to lose.”

“I know,” Steve said. “We’re just laying the groundwork for an appeal.” “I know, but I hate to lose.” “Stick with me. You’ll get good at it.” So there you have it. I enjoyed the jokes, and I enjoyed the complicated plot. Make that “really enjoyed” and “really complicated.” But I have a couple of comments to make – not guesses, you understand – but just an observation or two. Parodies are fine – can this be anything else? – but some people may not like the razzing of their heroes. The F-word was never heard in any of Erle Stanley Gardner’s novels, but it is in this one, and several times over. Parodies can also fizzle, and badly, when the subject of the parody is no longer very popular or perhaps not even remembered. By the time Steve Winslow’s run of adventures was over, Perry Mason had long since vanished from the bookstore shelves and the TV screen, or very nearly so. I have an uneasy feeling, and maybe you realize it too, that these are the guesses I was going to make, after all. Here are some more: Maybe Parnell Hall got tired of the series himself, or maybe even a little more likelier, became weary of thinking up really complicated mysteries for a really quick-witted attorney, dedicated (sort of) and (in this case) underappreciated secretary, and long-suffering private investigator to solve. I guess I could ask, and I think I will.

January

2006

ROBERT LEE HALL - Murder on Drury LaneSt. Martin’s, paperback reprint; October 1993. Hardcover edition: St. Martin’s, November 1992.  Checking back on

Hall’s career, he seems to have

worked exclusively in the historical mystery subgenre. In doing

so, he has also been no slouch at all in choosing either characters or

period settings. Here’s what I found, in terms of his

crime-oriented fiction: Checking back on

Hall’s career, he seems to have

worked exclusively in the historical mystery subgenre. In doing

so, he has also been no slouch at all in choosing either characters or

period settings. Here’s what I found, in terms of his

crime-oriented fiction:Exit Sherlock Holmes. Scribner’s, hc, 1977. Playboy Press, pb, 1979. The King Edward Plot. McGraw-Hill, hc, 1980. Critics Choice, pb, 1987. * Benjamin Franklin Takes the Case. St. Martin’s, hc, 1988; pb, 1993. Murder at Saint Simeon. St. Martin’s, hc, 1988. No paperback edition. * Benjamin Franklin and a Case of Christmas Murder. St. Martin’s, hc, 1991; pb, 1992. * Murder on Drury Lane. St. Martin’s, hc, 1992, pb, 1993 * Benjamin Franklin and the Case of the Artful Murder. St. Martin’s, hc, 1994; pb, 1995. * Murder by the Waters. St. Martin’s, hc, 1995; trade pb, 2001. * London Blood. St. Martin’s, hc, 1997. No paperback edition. The Ben Franklin cases of detection, of which Murder on Drury Lane is one, are marked with an asterisk. Sherlock Holmes made an appearance only in Hall’s first mystery. Murder at Saint Simeon takes place at the California mansion of William Randolph Hearst, with Marion Davies, Louella Parsons, Jean Harlow and Charlie Chaplin all making at least cameo appearances. That leaves The King Edward Plot, which takes place in England in 1906, during the reign of Edward VII, and one online source describes it as “the first novel-length story to feature Holmes as a character.” This does not appear to be so. Holmes’s appearance is not mentioned in a Kirkus review of the book, and the statement seems in itself to contradict the existence of Exit Sherlock Holmes. Other mystery novels that Holmes had a role in and which also came before Hall’s first book are: Ellery Queen [Paul W. Fairman], A Study in Terror, Lancer, 1966. Michael & Mollie Hardwick, The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes, Mayflower (UK), 1970. Nicholas Meyer, The Seven-Per-Cent Solution, Dutton, 1974. Philip José Farmer, The Adventure of the Peerless Peer, Aspen, 1974. Frank Thomas, Sherlock Holmes Bridge Detective Returns, Thomas, 1975. Don R. Bensen, Sherlock Holmes in New York, Ballantine, 1976. Richard L. Boyer, The Giant Rat of Sumatra, Warner, 1976. Nicholas Meyer, The West End Horror, Dutton, 1976. Austin Mitchelson & Nicholas Utechin, The Earthquake Machine, Belmont, 1976 – Hellbirds, Belmont, 1976. I may have missed one or two, but I don’t believe many more than that. Keep in mind that this is a list of novels only, and that I deliberately attempted to avoid self-published works. Ever since 1977 (what happened then, timewise?) the dam has burst, and Sherlock Holmes has unquestionably become the one single fictional character, detective genre or not, who has appeared in the works of more novels by other authors than any other. (You can question the statement, if you like, as long as you can come up with an alternative.) I seem to have gone off on a tangent here. The Sherlockian connection that exists in The King Edward Plot, and strongly so, is that two of the four amateur detectives who uncover the plot reside at 221A Baker Street. One of them nicknamed “Wiggins.” I will have to read it. Mr. Benjamin Franklin is getting restless, I am sorry to day. The book I have just read is about him, and he is being neglected. Here is a quote from page two. Franklin’s son William, a law student while in London, has just walked into the home where the Franklin entourage is staying, but he is unable to talk about the experience he has just had: Mr. Franklin wore his

customary brown worsted suit and black, buckled shoes. He

sighed. “As my son’s voice appears disarmed, mine must

slay the silence; viz.: he set by the law for the Theatre Royal in

Drury Lane, where he saw the play. Some soubrette has stole his

heart – and his tongue with it.”

He lifted an inquiring brow. “Did I hit the mark?

Did your enchantress dance in the pantomime?”

“Desdemona,” breathed William Franklin. “She played Desdemona.” He blinked, as if waking. “But, Father, I did not tell you that I went to the theatre. Indeed I have not been in my chamber since midmorning.” If Mr. Franklin’s explanation behind his deductive reasoning processes does not match that of the master, the attempt is well taken, at least by me, and the language is well appropriate for the tale that follows. Telling the story is Nick Handy, a twelve-year old lad who is Mr. Franklin’s illegitimate son. (Franklin made more than one trip to London, and there is a story behind this, one that was told in the first installment of the series. See above.) Actually the language, the vocabulary and the insight of the narrator is far beyond those of a twelve-year-old boy, but if you assume that Nick is rather precocious and add some sense of wonder, you will soon not notice. The year, lest I forget to mention it, is 1758, and Drury Lane (as the title aptly suggests) is the center of the mysterious misadventures taking place. David Garrick hires Ben Franklin to investigate, who obligingly allows young Nick to tag along, making sketches of the various places they go and the people they meet. It also turns out that Mr. Franklin is a pioneer in the field of fingerprints and handwriting analysis, but it is the later – with regard to the threatening notes that Garrick has been receiving – that is the more important of the two this time around. The pace of the tale is leisurely, to say the least. Perhaps more important to the mystery, until the end, of course, are the sights and sounds of the theater itself, as well as the area surrounding, bit players included. Other famous personages have roles as well: Sir John Fielding, Dr. Samuel Johnson. Horace Walpole attends a play, as does Tobias Smollett. A tremendously well-manufactured atmosphere is present, in other words, with a melodramatic ending that fits the mood perfectly. If the detection takes second place, it is only a minor quibble on my part to say so.

January 2006

LESLIE CAINE - Manor of Death  Dell, paperback original; 1st printing,

February 2006. Dell, paperback original; 1st printing,

February 2006.I do my best to keep up to date with all of the mysteries that come out every month, or at least those that come out in paperback. Honest, I do. I buy almost all of them, but I have to confess, at 30 or so a month, that averages out to a book a day, and in my reclining years it takes me two or three days to read a detective novel, and those are on the good days. You do the math. And there are all of the older books in this house to be read. This book by Leslie Caine came out in February, and it’s being reviewed in February. Did that happen last month? No. Will it happen in March? We will have to see. I’ll give it my best shot, but I will also promise you this: No promises. There are two previous books in Caine’s “Domestic Bliss” series, namely: Death by Inferior Design.

Dell, pbo, October 2004.

False Premises. Dell, pbo, June 2005. Take a look at the short amount of time between these books. No wonder I feel so bad. And do you know what else? All of the books are nearly 400 pages long. The lady writes faster than I can read, and I’m not kidding. Here’s a quick recap of the series, using Amazon.com as a guide. In Inferior Design, in trying to determine which of three couples are her real parents, two sets of which end up being killed – can that be right? – home decorator/designer (and primary series character) Erin Gilbert ends up nearly being murdered herself. In Premises, Erin finds that the antiques that she has used to decorate a wealthy client’s home have all been replaced by fakes. Her “nemesis” in these three books, if you care to call him that, segueing into Manor of Death now as well, is her primary competitor in Crestwood CO, Steve Sullivan. (If you don’t get the play on names, let me be blatant about it.) Sullivan is, of course, also a strong quasi-romantic interest in the stories as well. The major events in Manor occur in the house next door to the one where Erin is currently renting space for her and her cat to live. It seems as though the ghost of a young girl who fell, committed suicide, or was murdered forty years ago has now come back and is haunting the present inhabitants. Erin’s involvement is guaranteed since she has been hired to remodel the house, including the girl’s former room and the upstairs tower from which she met her death. Erin, who tells the story in first person singular, is appropriately smart and sassy, but the pacing is oddly off. The opening premise runs on to great length, with only the ghostly happenings (supposedly) and a seance to keep one’s interest alive. Or as you very well may be thinking, my interest, at least. With home decorating such a powerfully significant part of Erin’s life, you might question whether or not I am among the intended readership for this book, and that would probably be a fair inquiry to make, if you were to make it. (Not that home decorating is not a manly pursuit, you understand, don’t you?) On page 106, there is at last a death to investigate. By this time in the series Erin has become a good friend with the primary investigating officer (female and in no way competition for Sullivan), and as good friends do, the police politely make themselves (relatively) scarce. This allows Gilbert and Sullivan to combine forces and dig up the necessary clues from the past – high school yearbooks and the like – on their own. By page 273 the story has finally started to move into higher gear. I went along for the ride, but to tell you the truth, by that time all of the squabbling neighbors and their ofttimes trifling concerns had largely taken their toll on me. The mystery is not bad. The problem is that it’s too small for the book. I’ll take that back. That was my problem, possibly gender based, and it may not necessarily be yours.

February 2006

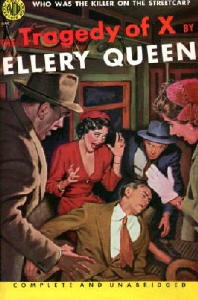

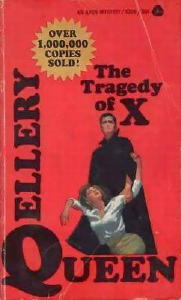

Charles Scribner’s Son; hardcover; First Edition, 1940. Even though there is a hint in the last paragraph that Inspector Steve Hamilton of the Bermuda Police Department may at some later date have another case to solve, it didn’t happen. This is it, the only case he ever had (one that was recorded for posterity, that is) but nonetheless, it’s a good one. Better than good, as a matter of fact. Something occurred to me while reading this book, though, and I’m not exactly sure why it’s never occurred to me so strongly before, since I’ve known it all along, but this is what it was. That the settings of the mysteries that are part of the period that’s commonly known as the Golden Age of Detection – and 1940 is almost exactly in the center of the time frame, or just afterwards – that the setting and people involved were almost always of the upper crust, the jet set (before there were jets) the rich or the artsy or both. The private eyes hung out in the gutters of society. The socialites had their world, and a certain segment of the population liked their detective work to take place in that world, not that they were part of that world, but that they enjoyed the opportunity to take a peek into that world and (perhaps) to see segments of that society broken down, just a little. As you must have gathered by now, that’s the kind of mystery this one is. And with the youngish Inspector Hamilton’s kid sister Joan romantically involved with the owner of the estate on the island just off Bermuda, he’s also there on the scene before the crime of murder is committed. What this book is also about, and once again something which is also very common in books taking place in the Golden Age of Detection, is a murder that takes place in a somehow isolated locale, in this case an island, and therefore resulting in only a limited number of suspects to be concerned about. (Well, almost.) Which includes the following: an young actor and a young actress, a man-about-town and his wife, a famous director’s wife and a famous artist, female. Not to mention the host and one mystery guest, whom everyone seems to know and seems to have seen even before the surprise is announced. Besides being involved with the host, Tony Bound, and not necessarily to Inspector Hamilton’s pleasure, his sister Joan is also his “Watson,” as she amusingly discovers that a murder investigation is something very much to her liking, eavesdropping in on the questioning of the suspects, making timetables, and all of the other accouterments and other apparatus of solving a crime. Either you like timetables in your detective fiction, or you don’t, but I do, even though I also like a private eye novel that dwells down in the lower echelons of society as much as anyone else. The detective work in this book I thought was excellent. Worthy of a Queen? Yes, even so, and once again, even with the cliched situations and settings that make themselves so noticeable that you cannot help but stumble over them, all I can say it that is it a shame that Joan never had the chance to help her big brother out like this again. UPDATE: This was the only work of crime fiction that David Burnham (1907-1974) produced, but Bill Pronzini, who provided the scan of the dust jacket above, suggests that he perhaps was also the author of Winter in the Sun (Scribner’s, 1937), a book about ranch life in the Arizona desert. The name’s the same, and the publisher’s the same, so the chances are better than good that it’s a match. February 2006

HILARY BURLEIGH - Murder at Maison Manche Hurst & Blackett Ltd., British hardcover. First Edition; date not stated but in fact 1948.  Another one-shot detective novel from an all-but-unknown author today, but not one, in my opinion, that is nearly as successful as the entry above. To begin with, to set the scene, so to speak, let me quote from early on in the affair, from page 13:

The salon at Pierre Manche’s was never crowded. His

clientèle was too carefully chosen for that. One could say

with truth that it was chosen, for in these days the distinction of

being dressed by Mache is so eagerly sought that it is more often the

case of Manche choosing whom he would dress than of Manche seeking

clients. To have admission to his dress parades was a

distinction. Tickets took the form of invitations to an exclusive

function, and men and women came as guests to that beautiful room,

where they were personally welcomed by the little fat man at the head

of the stairs and regaled with cocktails or sherry of undoubted

vintage, as a prelude to the display of fashion.

So all right, then. Both of the ingredients for a successful Golden Age Mystery are present, as touched upon in my comments on the Burnham book. Essential setting ingredient number one: A house (or even better, a manor) full of glitzy people, or an exclusive business establishment of some sort, or some other meeting place of the rich and famous. Essential setting ingredient number two: When Gleba, Mache’s most beautiful mannequin (model) is found murdered immediately after a showing of a wedding dress (page 18) there has been only limited access to the salon and the dressing rooms behind. Only the people on the premises can be presumed to have been the killer. One difference between this book and the previous one is how early on the victim’s death occurs. Here it seems almost too soon, only eighteen pages in, and there has been no time to know anything about the girl, except that she wears clothes well, and thus there has been no time for the reader to react properly and have any feeling about such minor matters such as rationale, reason and motive. In this book, matters like these are left to be revealed only gradually, but the major one as far as I will reveal to you is that the wedding dress Gleba had been wearing just before she was killed was that of a woman in the audience with whose fiancé she (Gleba) recently had had an affair. The detective from Scotland Yard who is quickly called to scene is Chief Inspector Tellit. He is described in detail on page 74 as a thick-set man dressed in well-cut and utterly uninspired clothes, ugly hands, far from good-looking but with an often kindly look in his deep blue eyes. In general, however, “he was considered a hard man” as far as crime and criminals are concerned. This is far from his first brush with a mysterious death, you may also be interested in knowing, since on page 48, his assistant, Det. Sgt. Fry feels “content that he was once again with Tellit on a murder case.” Tellit is a man for keeping track of details, gathering together scraps of information and putting them together like pieces of a jigsaw, as we are told on page 101. Every so often the author (in the guise of Inspector Tellit) feels the need for a recap and a provisional summing up, a device that seems worn-out today, but it is one which this reader, at least, almost always finds welcome. If this is not as gripping a detective yarn as David Burnham’s one was, it is for two reasons, the first being the huge amount of coincidence that is involved to put all of the actors on the scene at precisely the right moment, with the right means (a mysterious snake venom manufactured only in one lab in South America), the right motive and the right opportunity. Secondly the pacing is oddly off. In particular, the book also seems to “end” at page 180, with 27 more pages to go, and another character, previously relegated to the background is needed to emerge to set up the “real” solution. One more coincidence, and usually for a suspension of disbelief, all that an author is usually allowed is one, or no more than two. The right ingredients are present, in other words, but they get themselves muddled up a bit at the hands of an author whom I will call an amateur – without knowing anything else about her – in the finest sense of the word. February 2006

DEAN OWEN - Juice

Town DEAN OWEN - Juice

TownMonarch 290; paperback original. First printing, December 1962. (Cover art by Rafael M. deSoto.) As an author, Dean Owen (born Dudley Dean McGaughey, 1909-1986) is perhaps better recognized for his westerns than for his crime fiction, but today I don’t imagine he’s a well-known name in either field. If you follow the link, however, you’ll find a fairly lengthy and what I hope is a complete checklist of the fiction he wrote, starting out in the pulps, then almost exclusively paperback originals. Of the books listed in Al Hubin’s Crime Fiction IV, I found two errors. First of all, Juice Town is listed as only a marginal entry. Not so, as you will see in a minute. And A Killer’s Bargain (Hillman, pbo, 1960) is included, and I don’t believe it should be. From all I can tell without having it in hand, it’s a western, with no more crime elements than almost any other western has. And of the “sleaze” books Dean wrote, some may have definite crime elements, but while they’re included in the checklist, I don’t own any of them, so someone else will have to report in on those. (And in fact, two of the hard-to-find digests Owen wrote as Hodge Evens have since been confirmed as having substantial crime content.) It’s been a long time since I’ve read a book like this one. It starts out really, really tough and doesn’t let up until it’s over. It doesn’t matter too much if it’s also only a song with only one note. The one note is like a small incessant drumming in the background that just doesn’t go away until the book is over. In a sense (speaking of westerns) this is a western in theme, at least, if not in reality. One guy in a white hat comes to town and cleans it up, one guy against the mob, one guy who’s left himself vulnerable with a wife and kids, but he does his job anyway. The guy in this book is Del Painter. Out of a job and looking for work – there’s a story behind that as well – he is persuaded to return to his home town of Southbay, California, and to join the same police department that he was so proud his Uncle Ray, now deceased, was a member of for so long. Little does Del know that his uncle was a crook, that the entire police department is crooked (and rather openly so), and that he on his first day on the job is expected to be a crook as well. Juice, in the sense of the title, means protection, as it is carefully explained to Del on page 34, and the police in Southbay make out very well, including the use of the services of the local ladies of the evening whenever they feel they have a need for them. Del has a hard head, though, and hard heads make for harder enemies in towns like this. He does make a few friends, however, although it difficult to tell at times – well, most of the time – on which side some of the friends are. At only 144 pages in length, this book can be read in only one evening, and probably in only one sitting. And even though several weeks later you are probably not very likely to remember much of the details of what is admittedly a rather minor effort, this vividly jagged portrayal of a town with such a blatant disregard of the law may stick with you a whole lot longer than you think it will, when you’re done with it.

February 2006

OCTAVUS ROY COHEN - Romance in the First Degree Popular Library 88; no date stated [1946]. Hardcover edition: Macmillan, 1944. The copyright date is 1943, which led me to a quick investigation and the discovery that this very enjoyable detective novel first appeared in several installments as a four-part serial in Collier’s in December of that year. I don’t collect Collier’s, even though I’m often tempted to, as there’s quite a bit of genre fiction to be found in the magazine, including both mysteries and westerns. But just as it is with The Saturday Evening Post, the oversized format makes it both awkward to read and to store, and so (so far) I’ve been able to resist. At any rate (sometimes I do digress) this book would come in Cohen’s later period, if he had periods, but if he did, his early period has been covered by Jon Breen in a short article he did a year or so ago. If you follow the link, you will also find a comprehensive bibliography of Cohen’s crime fiction. As far as when one period ends and another begins, your guess is as good as mine. This may be the first book by Octavus Roy Cohen I’ve read, but you can believe me when I say that it won’t be my last. The opening premise is rather strange. Straight out of the army with a now-healed war wound (but with several missing toes), Jerry Anthony is hired by Warren Cameron, the man he used to work for, but as an unofficial investigator to find out what kind of trouble his (Cameron’s) son and new wife have somehow gotten themselves into. Since Jerry needs a place to stay, there is no better place than the Cameron apartment, where Alan, Linda and their baby are also living. That’s not the unusual part. Cameron is also the father of Rita, the girl Jerry was supposed to marry, but who jilted him while he was overseas. Now engaged to someone else, she still lives at home, as does Sandy, the youngest daughter, who has been in love with Jerry since she was 16. (She is only a few years older than that now.) It’s quite an arrangement. You might think that this is going to be one of those upper class mysteries I was talking about a while before, one involving the Park Avenue set, but No Sir or Ma’am, this is something else altogether. Following Alan and Linda one night to a desolate road house on Long Island, Jerry enters after they have left to find a dead man inside, at which moment he (Jerry) is clunked on the head. From which point on, when he wakes up, the mob is involved – the dead man being a close associate of head mobster Leo North – and so is the dead man’s girl friend; another mobster in love with the girl friend; a somewhat unsavory private eye named Dave Larric who somehow seems to know too much and somehow not enough; and a vivacious young Broadway star named Holly Hamilton. While Jerry knows he did not do the killing, he is not too sure about Alan and Linda, but even though they are not talking, he figures that it is part of his job to protect them. How everyone else fits in, he has no idea. This is one of those cases that gets screwier and screwier one  chapter to the next, nor in the meantime is

there any shortage of death and skullduggery at almost any level you

can think of. chapter to the next, nor in the meantime is

there any shortage of death and skullduggery at almost any level you

can think of.Assisting Jerry in sorting through the facts and the clues is Rita’s younger sister Sandy, and if you don’t grasp onto the fact that some romantic (and only slightly sappy) fireworks are going to go off in that regard, you simply have not read enough fiction, young sir or lady. As for Rita, she is sort of steamed about this, and before I forget, here is Jerry’s description of the older sister when he first sees her for the first time in this country after their broken engagement (from page 21): She was a full two inches taller than

Sandy which made her tall enough to be called statuesque. She had

a figure which couldn’t miss the same description What every

woman wants, she had. If you were inclined to think along certain

lines, you could call her voluptuous. I called her

voluptuous. It was a nice thing to call her, and it fitted.

She had provocative gray-green eyes and the richest golden hair that I

ever saw.

She was in a dinner dress. She wore dinner dress every chance she got. She had at least two good reasons. [...] She said, “Jerry! It’s good to see you again.” She said it in a deep, throaty voice that sent tingles up and down my spine. She put both hands in mine. I almost upset my cocktail putting it down to make the most of this opportunity. [...] Already I felt myself looping, just as I had in the old days. I even said “Nuts” to the still small voice that was warning me to watch my step. Besides doing descriptions very well, Cohen has a good hand with dialogue as well, not only here, but throughout the book. Eventually, after Jerry has filled his eyes to the brim, a paragraph or two later his brain seems to take over again. “Magnificent,” I said. “And it all

belongs to someone else.”

I heard a chuckle. I couldn’t tell where it came from, but I suspected Sandy. This hasn’t anything to do with the mystery, but byplay like this surely makes the tale Cohen tells go down more smoothly, not that it needs a whole lot of help. Surprisingly enough, all of the clues eventually fit and make a coherent whole out of what seemed to have been an impossible tangled mass of events and unknown motives and relationships. It is all choreographed so beautifully that – Um. I should not get carried away so dramatically. This is all relatively speaking, you understand. It is not Tchaikovsky I am talking about here, but perhaps you know what I mean without forcing me to finish the sentence above. And let me not forget the private eye whose presence is both peripheral and essential to the story, Dave Larric. In terms of doing down-to-earth detective work, Jerry Anthony is only an amateur. Larric is the professional, straight from the pulp magazines. Although he may as a result be somewhat stereotypical in being so, I wonder (and would really like to know) if he ever appeared in any other of Cohen’s novels.

February 2006

BRUCE ALEXANDER - Rules of Engagement Berkley, paperback; 1st printing, February 2006. Hardcover edition: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, March 2005. This is the first of Bruce Alexander’s “Sir John Fielding” detective novels that I’ve read, and no, I did not realize it until after I’d picked it out to read that this is also the last one that Alexander ever wrote. Bruce Alexander was not his real name – you probably knew that, and so did I. Bruce Cook (1932-2003) wrote eleven mysteries as “Alexander.” Under his own name he had five earlier ones, four of them with Antonio “Chico” Cervantes as the leading character. Now it gets interesting. (I will get back to Antonio “Chico” Cervantes in a minute.) Cook also was at least in part responsible for writing William J. Coughlin’s last book after he (Coughlin) died, The Judgment (St. Martin’s, 1997). I’m quoting from Al Hubin in Crime Fiction IV now: “Apparently written by Bruce Cook from a beginning by Coughlin, then finished and polished by widow Ruth Coughlin.” The reason is that this is interesting, is that this is also exactly how Rules of Engagement got written. From the back cover, and quoting again: “He (Bruce Cook) died in 2003, having completed most of Rules of Engagement, and left notes on how the rest of the story unfolded. John Shannon, author of the highly praised Jack Liffey series, most recently Dangerous Games, completed the novel with Bruce’s wife, Joan Alexander.” As coincidences go, it would be rather minor, but was it a coincidence? Probably not. The idea was there, and the Bruce Cook and his wife simply carried it out in the same way it had been done before. And as you can easily imagine, there are both pluses and minuses in doing so. Before getting into that, and to Sir John Fielding and what the book (and the series) is about, I promised to tell you something about Chico Cervantes. The Thrilling Detective link will tell you more, but perhaps it suffices to say that Cervantes was a Mexican-American ex-LA cop turned private eye whose stomping grounds were (as you probably already guessed) Southern California. His four recorded cases (1988-94) did not seem to turn the mystery fiction world on fire, and in fact, only one of the four, the first, Mexican Standoff, was ever published in paperback, the other three only in hardcover. For whatever that tells you. In any case (no pun intended) the year the last Cervantes book came out, 1994, was the same year that Blind Justice, the first Sir John Fielding novel appeared. Cook, as Alexander, at the age of 62, had hit the equivalent of pay dirt. Here is the complete list of the highly popular Fielding books. (I have them all. They are still in the TBR (To Be Read) portion of the basement. Unfortunately.) All were published in hardcover by Putnam and in paperback by Berkley. The dates are of the hardcover editions; the paperback generally appeared a year later.

Sir John Fielding, as I’d better make sure I tell you, was the blind English magistrate who was the real-life founder of London’s first true police force, the Bow Street Runners, in the mid-to-late 1700s. What is interesting about one of the books above, An Experiment in Treason, Benjamin Franklin makes an appearance, although unlike in Robert Lee Hall’s series of books, in Alexander’s novel he (Franklin) is a suspect, not the detective, while Fielding is only a (relatively) minor character. In the books by Bruce Alexander, Fielding’s household and close-knit circle of friends and close acquaintances takes center stage, filled to abundance with family, servants, many of which (if not most) are fictional. Especial note should be made of the narrator of the tales, one Jeremy Proctor, Fielding’s protege with him throughout the series, an orphan taken under his wing as a dogsbody, now all of eighteen and Sir John’s clerk at the Bow Street Court. The title comes in part from the fact that Jeremy is engaged to be married to Clarissa Roundtree, the other orphan taken in by the Fieldings, Clarissa as Lady Fielding’s general factotum, and as the book begins, he (Jeremy) is beginning to wonder greatly about his future. (On page 241 there is another context in which “rules of engagement” come into play.) The mystery, which is extremely slight, but of course it needs to be mentioned, is that of the strange death of Lord Lammermoor, who has recently jumped to his death from a bridge while crossing the Thames alone. Several chapters later (or to be precise, in Chapter Three) the case is all but solved when Fielding and his entourage are entertained at the theater by a practitioner of “animal magnetism” and/or “mesmerism.” The only question that remains (to the reader, that is) is who is responsible, and while I cannot reveal his/her name, you will know as soon as he/she enters the story. (Ventriloquy is also an important factor, but my telling you that will neither enlighten you further, or less.) One hopes for more, but more there is not, save 200 pages in which a great happens, but very little of any consequence. All in all, what the authors in consultation have provided is nothing less than a worthy attempt to tie up some loose ends for the readers who have followed the series from early on, but not all of them (the loose ends, that is). Life happens, and that is what is left for the reader to contemplate. This is one of the aforementioned pluses. For someone expecting a detective story with some solid, down-to-earth detective work going on, either Mr. Alexander did not have one in mind, or if he did, neither his wife nor John Shannon were able to build one out of the notes that he left them. This is one of the aforementioned minuses. For the record, the pluses outweigh the minuses, but personally, coming in at the end as I did, I left with a feeling of disappointment that, strangely enough, I sincerely wished I didn’t. If you’d like to call my verdict “mixed,” you’d certainly be right. I wouldn’t deny it at all.

March 2006

DAVID DODGE - Shear the Black Sheep Popular Library 202; paperback reprint; no date stated, but circa 1949. Hardcover edition: The Macmillan Co., 1942. Magazine appearance: Cosmopolitan, July 1942. After I finished reading this, the second murder mystery adventure of accountant detective Jim “Whit” Whitney, I went researching as I usually do, and it didn’t come as any surprise to learn (from a website devoted to David Dodge) that Dodge was also a CPA by profession, and that he started writing mystery fiction only on a dare from his wife. Although Dodge went on to another series (one with private eye Al Colby) and after that several standalones, there were only four books in the Whit Whitney series, to wit:  Death and Taxes. Macmilllan, hc, 1941. Popular Library 168, pb, 1949. Shear the Black Sheep. Macmillan, hc, 1942. Popular Library 202, pb, 1949. Bullets for the Bridegroom. Macmillan, hc, 1944. Popular Library 252, pb, 1950. It Ain’t Hay. Simon & Schuster, hc, 1946. Dell 270, pb, 1949 [mapback]. Sorry. I couldn’t resist. You can find much more detailed entries for each of these books at the David Dodge website, which includes a complete bibliography of all of his other books, both fiction and non-fiction. Not to mention his plays, his magazine stories, the articles he wrote and all of the radio, TV and movie adaptations of his work, the most well-known of which is TO CATCH A THIEF, the Cary Grant and Grace Kelly film from 1955. Comprehensive is an understatement, and it’s definitely worth looking into, just to see a bibliography done right. As for Whit Whitney, his home base is San Francisco, but in Shear the Black Sheep he is talked into taking a case in Los Angeles over the New Year’s Eve holiday weekend. Against his better judgment, he agrees to check into the activities of a client’s son, who seems to be spending too much of his father’s money in the business they’re in. They’re a wool brokerage firm – hence the title. The son has also left his wife and new-born baby. Is there another woman? Assisting Whitney – or making her way down to LA on her own to spend the holiday with him, or as much of it as there is left after Whit’s investigative duties are over – is Kitty MacLeod, “the best-looking girl in San Francisco, and pretty clever as well,” as she’s described on page 12. I’ve not read the first book in the series, and make no doubt about it, I will, but in that book (according the short recap on just about the same page) Whit’s former partner was murdered and at the time, Kitty was his wife. It’s now six month’s later, and Whit and Kitty are very close. Whit is beginning to worry that some of his colleagues are starting to talk. There had even been some talk at the time that Whit had had something to do with Kitty’s ex’s departure from life, and getting out of the jam at the time seems to be the gist of the story in Death and Taxes. But that was then, and this is now. There is indeed a woman involved, as suspected – getting back to the case that Whit was hired to do – and the woman leads to a hotel room, and in the hotel room are ... gamblers. A crooked card game, and the black sheep is getting sheared. It is all sort of a light-hearted tale, in a way, but then a murder occurs, and a screwy case gets even screwier – in a hard-boiled kind of fashion. Let me quote from page 160. Whit is talking to his client, who speaks first:

“I don’t think it’s wise to

interfere with the police, Whitney.”

“I won’t interfere with them. I’d cooperate with them except that they’ve told me to keep out of it. I want you to know how I feel, Mr. Clayton. You hired me to find out what Bob was doing with your money, and to stop it. I found out what was going on, but I thought the best way to stop it was to let these crooks get out on a limb, and then saw it off behind them. I thought I could protect your money and show Bob what was happening at the same time. I guessed wrong. I don’t know who killed [...] or why he was killed, and I don’t think I’m responsible for his death, but I’m in a bad spot and I’d like to bail out of it by myself – for my own satisfaction. The police needn’t know what I’m doing. I don’t have to tell you that I don’t want to be paid for it, but if you haven’t any objection, I’ll try to find out who killed [...] and get your money back.”  Here are a few lines from page 170, at which point things are not going so well:

He got off the bed and prowled

thoughtfully around the room in his stocking feet, still holding the

beer glass. What would Sherlock Holmes do with a case like

this? Probably give himself a needleful in the arm – Whit drained

his beer glass – and deduce the hell out of the case.

Whit tried deduction. These were the days when mystery thrillers were also detective novels. After a long paragraph in which Whit tries out his best logic on the tangled threads of the plot, and who was where and when and why: It was a pretty wormy syllogism. As

a deducer Whit knew he was a lemon when it came to logic, and he was an

extra-sour lemon because he didn’t know enough about Bob Clayton to

figure out what he might do in a given set of circumstances. Such

as having a pair of football tickets to dispose of, for example.

Ruth Martin might have known where they went, but didn’t, ditto Mrs.

Clayton, ditto John Clayton. Jack Morgan was the next one to try.

What’s interesting is that Kitty has more to do with solving the case than Whit does. Things happen rather quickly at the end, and if all of the loose ends are (or are not) all tied up, no one other than I seems to think it matters, as long as the killer is caught – who was not someone I suspected, or did I? I probably suspected everyone at one point or another. I also wonder if what happens on the last page has anything to do with the title of Whit Whitney’s next adventure in crime-solving. Read it, I must. And I will.

March

2006.

FRANK G. PRESNELL - No Mourners Present  Dell 646, paperback reprint; no date stated,

but circa 1953.

(Cover by Robert Stanley.) Hardcover edition: William Morrow

& Co., 1940. Dell 646, paperback reprint; no date stated,

but circa 1953.

(Cover by Robert Stanley.) Hardcover edition: William Morrow

& Co., 1940.The jacket of the hardcover edition suggests that the book may have been published as by “F. G. Presnell,” but any final judgment on that would have to wait until the title page has been examined, the final and only arbitrator on matters of bibliographic significance like this. There is nothing on the Internet that discusses Frank G. Presnell (1906-1967) nor his three mysteries in any significant way. At the moment, all I have to tell you about him personally is what Al Hubin says in Crime Fiction IV: “Born in Mexico; educated at Antioch College and Ohio State Univ.; designer and engineer; lived in Ohio for 40 years, then in Los Angeles.” Which is a start, but what it doesn’t say is why Mr. Presnell wrote two good books in 1939 and 1940, both with high-powered (and hard-boiled) practicing attorney John Webb, then not another novel until 1951, and Webb is not in it. For the record, here is a list of Presnell’s only contributions to the world of crime fiction: Send Another Coffin. Morrow, hc, 1939. Detective Book Magazine, Winter 1939-40. Handi-Book #39, pb, 1945. No Mourners Present. Morrow, hc, 1940. Dell 646, pb, 1953. Too Hot to Handle. M. S. Mill / Morrow, hc, 1951. Dell 593, pb, 1952. I had not known until I looked it up, but a movie was made of Send Another Coffin, one I’ve never seen, but I believe I shall have to purchase it. The title of the movie is SLIGHTLY DISHONORABLE (United Artists, 1940), and besides Pat O’Brien and Ruth Terry as the two leading characters – I’ll get to that in the next paragraph – also in the film are Edward Arnold and Broderick Crawford.

In the movie, Ruth Terry is credited only as “Night Club Singer,” but in the book she has a name: Anne Seymour. In the followup book, the one at hand, she has another name: Anne Webb. A substantial part of No Mourners Present is the mystery novel, of course – and I’ll get to that in moment too – but another significant portion of it, one mixed up one with the other, concerns the domestic life of the two newlyweds. The tough attorney John Webb is deeply in love with his wife. That much is apparent right away. He also seems to wonder how it is that he is so lucky to have her in love with him. Her background as a singer seems to be a concern to him as well: how well will she fit in with the wealthy set that he sometimes hangs around with? Without revealing too much, I think Anne Webb is smarter in many ways than he thinks she is, and that she can hold her own in his world very well indeed, and maybe even better. John has nothing to worry about. Of course there is no way of knowing. Two books with the Webbs, and that was all there was. If I had known while I was reading this, the second one, it might have influenced the way that I read it, but of course we will never know that, either. For Mr. Presnell, we must assume that the war intervened, and life and a family and earning a living. The town in which John Webb is a man with considerable political clout is not named, I don’t believe, and since Hubin doesn’t suggest a setting (I just checked) neither do I believe it is a matter of my missing it. With very few preliminaries, the mystery gets into action right away, with Jake Barman’s murder taking place on page 15, one page after Webb very nearly slugs a radio news commentator for a remark he makes about Anne. Anne takes him to task reproachfully afterward. “Listen,” she says. “You’ve got to stop hitting people.” Barman is a partner in a building firm, or he was, and he also had ambitions of being elected governor. He is on the outs with his wife, however, which is a liability, especially since everyone knows that Julie Gilson, his secretary, is also his mistress. She is also the leading suspect as well, especially after she disappears completely from sight after Barman’s death. Without a client, Webb is only incidentally involved until Julie’s brother comes to town are hires him to help protect her name. Once hired, Webb goes immediately into Perry Mason mode. See page 40, and you will see exactly what I mean.  If you’re only in your 30s

or 40s, it may not seem like it – it’s too long ago – but 1940 was

still a time in this country’s history when if your company bucked

either the gangs or the unions, people were maimed for life. This

is the sort of thing that gets Webb’s blood boiling as well.

Here’s a long quote from page 45. He’s talking to the man he’s

working for who’s in charge of operations at a chain of cleaning

establishments. If you’re only in your 30s

or 40s, it may not seem like it – it’s too long ago – but 1940 was

still a time in this country’s history when if your company bucked

either the gangs or the unions, people were maimed for life. This

is the sort of thing that gets Webb’s blood boiling as well.

Here’s a long quote from page 45. He’s talking to the man he’s

working for who’s in charge of operations at a chain of cleaning

establishments. “... In the second place, even if I

didn’t give a good Goddamn whether Acme ever makes another nickel or

not, I’ve got a front to keep up. Why do you think people pay me

fancy prices to do things for them? Because they think I’m going

to lie down and let myself be walked on? Like hell they do!

They hire me because they know they’ll get grade-A effort,

anyhow. And how come I usually give them results besides?

Because the other side knows they’ll sweat for anything they get. [...]

If anybody from this damn

cleaning-and-dyeing-trades racket comes around here, you tell ’em to

talk to me.”

I mentioned Perry Mason a short while back. Perry was tough in his early days, but not as tough as John Webb. Here is a portions of his thoughts, his philosophy of action, you might say, taken from page 61:

Cabash was tough and vicious,

but he wasn’t smart. He’d start trying to bluff us, and when he

did, it was up to me to give him a chance to do nothing but wonder what

hit him. I didn’t know how I was going to work it, but you can

always figure out ways if you’re willing to use them.

As a word of warning, the book is a little too talky to be this tough all the way through, but when it is, it is. It earns high points as a detective novel as well, or at least it did with me, with plenty of twists and turns in the plot to keep Webb’s brain (and mine) working in as finely-tuned fashion as his brawn. The solution is not nearly as finely worked out as one of Perry Mason’s, however, containing as it does one small gap I haven’t quite yet figured out. Nonetheless, even if the mystery itself is not a classic that anyone will remember for very long, if there’s any in mourning at the moment, it’s me, wishing that there were a next one to read, and as much for the characters, I would advise you, as for anything else. Sadly to say, one more time, there wasn’t a next one to read at the time, and there isn’t now.

March 2006.

GEORGE HARMON COXE - Focus on Murder  Pyramid R-1259; reprint paperback, January

1966. Cover by Frank Kalan. Hardcover edition: Alfred A.

Knopf, March 1954. Hardcover reprint: Dollar Mystery Guild, June

1954. Previous paperback reprint: Dell 970, 1958. Pyramid R-1259; reprint paperback, January

1966. Cover by Frank Kalan. Hardcover edition: Alfred A.

Knopf, March 1954. Hardcover reprint: Dollar Mystery Guild, June

1954. Previous paperback reprint: Dell 970, 1958.What with two paperback editions and (more importantly) a book club edition, this should not be a difficult book to come across, if you all you want to do is to find one to read. In his prime, Coxe was not a bestselling author like Gardner and Christie, but if longevity has anything to say about it, his sales must have been steady if not spectacular. Coxe’s career in hardcover fiction began in 1935, with Murder with Pictures, also with Kent Murdock, the crime-solving news photographer who has the starring role in Focus on Murder, and it did not end until No Place for Murder. Kent Murdoch does not appear in this latter book, but private eye Jack Fenner does, and he also appeared in Murder with Pictures, his career in hardcover therefore lasting exactly as long as Coxe’s did. And here’s something interesting. While Jack Fenner appeared in 12 cases chronicled by Coxe, his only solo shot was that final one, and it did not appear until the author was 74. (After retiring from writing, Coxe himself lived another nine years, until 1984.) Coxe is probably best known for his series character “Flash” or “Flashgun” Casey, a tough Boston-based news photographer who began his crime-solving in the pages of Black Mask magazine, circa 1934, but (after a quick double-check to confirm this) Coxe wrote far many more novels in which Boston-based news photographer Kent Murdock appeared (23) than those in which Casey was the detective of record (only five). The difference in fame, such as it may be, is probably due to the fact that Casey had a long-running radio show named after him, and two movies based on his exploits, while Murdock had neither. Kevin Burton Smith over at www.thrillingdetective.com suggests that Murdock is Casey with the rough edges smoothed off. Given Casey’s early pulp fiction days, Kevin is probably quite correct in that assessment. The paths of Murdock and Casey also seem to have never crossed, and this only adds more credence that they were in fact one and the same person, only under different names. Although his roots were in the pulps, I would definitely consider Coxe as an author solidly in the Golden Age of Detection story-telling tradition, but if you do indeed come across a copy of this book, and if my review and other chatter convinces you to read it as well – which I certainly am going to do my best to do – be sure to strap yourself in for a fast-paced mixture of action and clues you have to keep your eyes on every minute of the way. Let’s get the basic plot out of the way first – or at last, depending on your point of view. Ralph Stacy, a colleague of Murdock’s at the Courier is found murdered shortly in his apartment after his (Murdock’s) departure, said colleague (as it turns out) having been a blackmailer in his spare time. That Murdock happened to have been in Stacy’s place of residence is important but not significant in the sense that he becomes one of the suspects – Lt. Bacon has worked with Casey before, and I’ll get back to this in a moment – but (as it turns out) an entire parade of suspects just happens to have been in and out of the apartment and/or lurking around the building both before and after Murdock comes on the scene, not all of them totally coincidentally. There is nothing like good old-fashioned (and dirty) blackmail to create a long list of suspects in the death of a blackmailer, not to mention a wife who has just moved out, a current girl friend, and a close boy friend of said girl friend, who just happens to be the jazz singer shown on the cover. Murdock is also personally offended in a personal sense, he being a true-blood newspaperman through and through, nor can the reader help be offended as well. Coxe also has (had) an excellent insight into the way people in the real world (mostly male, I concede, but far from entirely) react to tragedy and other things, which includes matters of right versus wrong, in a strangely tweedy sort of way. He also seems to have been quite the jazz aficionado. I won’t quote Murdock’s conversation with pianist Jack Frost about Art Tatum on page 80 – it’s rather long – but there is nothing said here about Tatum that anyone could possibly dispute. It’s dead on, in other words. By page 116, Lt. Bacon has (figuratively) thrown up his hands and asks Murdock, quite unofficially of course, to give him (Bacon) whatever assistance he (Murdock) can. And of course he (Murdock) does, again with neither the final flourish of a Christie or a Gardner – to pick a couple of prime examples out of the air – but with the somewhat subdued manner of a magician whose apparent casualness may catch you blinking, and with a slowly comprehending grasp of just how easily the unwary reader can be taken in.

March

2006

WILLIAM MURRAY - I’m Getting Killed Right Here Bantam; reprint paperback, July 1992. Hardcover edition: Doubleday, November 1991. You very well may know this, but the bad news is that William Murray, author of the Shifty Lou Anderson books, of which this is one, died last year (2005) at the age of 78. He wrote nine in the series, of which this is the first one I’ve read, and no, it will not be my last. Shifty, who tells the stories himself, is what you might call a “close up magician” by vocation and a steady habitue or patron of the racetracks by avocation. Here is a list – you were waiting for this, right? – of the nine Shifty Lou Anderson novels: Tip on a Dead Crab.

Viking Press, hc, April 1984.