Sun 8 Feb 2009

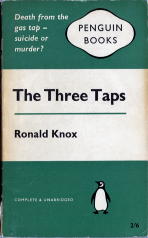

Review: RONALD KNOX – The Three Taps.

Posted by Steve under Bibliographies, Lists & Checklists , Crime Fiction IV , Reviews[18] Comments

RONALD KNOX – The Three Taps. Penguin 1451, UK, paperback, 1960. Hardcover editions: Methuen, UK, 1927; Simon & Schuster, US, 1927.

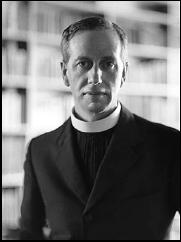

Born in Knibworth, Leicestershire, Ronald Knox was ordained a Roman Catholic priest in 1918, and with The Belief of Catholics in 1927 he became one of the UK’s foremost spokespersons for the religion. As most fans of early detective fiction know, he also dabbled in more mundane matters of more interest to us here. In fact was a prominent member of the exclusive Detection Club for many years, until he was requested by his bishop to cease and desist writing mere mysteries.

He is known perhaps in our circles more for his Ten Commandments for Detective Fiction than for his novels, here they are in short form, as stated in his introduction to The Best English Detective Stories of 1928:

II. All supernatural or preternatural agencies are ruled out as a matter of course.

III. Not more than one secret room or passage is allowable..

IV. No hitherto undiscovered poisons may be used, nor any appliance which will need a long scientific explanation at the end.

V. No Chinaman must figure in the story.

VI. No accident must ever help the detective, nor must he ever have an unaccountable intuition which proves to be right.

VII. The detective must not himself commit the crime.

VIII. The detective must not light on any clues are not instantly produced for the inspection of the reader.

IX. The stupid friend of the detective, the Watson, must not conceal any thoughts which pass through his mind; his intelligence must be slightly, but very slightly, below that of the average reader.

X. Twin brothers, and doubles generally, must not appear unless we have been duly prepared for them.

The longer version with commentaries and suggested exclusions, et cetera, can be found here.

Ronald Knox produced only six detective novels of his own, all but the first solved by one Miles Bredon, an insurance investigator for the Indescribable Company. This makes him a sleuth very much like a private eye in nature, but he’s no mean streets kind of guy. Small village life is the setting of The Three Taps, and along with him is his wife Angela, and I have to admit, she’s no slouch as a detective either.

Slowing the book down in the beginning is a long rambling preamble that assumes, first of all, that the reader knows what an Euthanasia policy is. I couldn’t find a single reference to such an agreement on the Internet, but I probably ran out of patience before I should have. From the context, though, I finally gathered that it was an insurance contract that before the policy holder reached the age of 65 paid off on the his or her death in the usual fashion, but then turned into an annuity making regular payment to the survivor, if he did.

Of course if the policyholder commits suicide before the age of 65, the heirs get nothing. This is the crux of the story. A man named Mottram, the holder of such a policy, is found dead of gas poisoning in the room in the inn which he was staying while on a vacation fishing trip. He’s under 65, but recently he’d tried to buy out his policy from Bredon’s insurance company, telling them that a doctor had given him only a few months to live.

Bredon makes a bet with his friend Inspector Leyland. Breton says his death was suicide (so his company doesn’t have to pay off), and Leyland says it was murder. And with the wager in mind, each looks for clues to back his version of what really happened.

It’s a complicated matter, and a beautifully constructed one, with lots of clues mixed in with the red herrings, double bluffs, hidden motives and of course no one tells (all) the truth. The denouement is even more complicated, so far as to be unreal, but truth (and fate) certainly does fall in strange and unexpected ways, so who am I to argue?

Besides the Euthanasia policy to confound the present-day reader, the matter also depends greatly (and quite naturally) on the gas taps in the dead man’s room: which of the three were on, and which were off, and when and why. For all except the last, or “why,” it would take a mathematician to follow the logic, but I plead guilty and admit that I fell asleep at the switch.

Overall then: this tale is definitely dated — much of the current crowd of mystery readers isn’t going get very far into this one — but it’s their loss. This is a beautifully and wonderfully constructed detective story.

Bibliographic data:

[Taken from the Revised Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin.]

KNOX, [Monsignor] RONALD A(rbuthnott). 1888-1957. Series character: Miles Bredon, in all but the first.

The Viaduct Murder (n.) Methuen 1925.

The Three Taps (n.) Methuen 1927.

The Footsteps at the Lock (n.) Methuen 1928.

The Body in the Silo (n.) Hodder 1933.

Still Dead (n.) Hodder 1934.

Double Cross Purposes (n.) Hodder 1937.

February 8th, 2009 at 11:47 am

I’ve always had a problem with the Ten Commandments of Detective Fiction. Maybe they worked for the classic puzzle type of detective story back in the 1920’s and 1930’s, but after that period my feeling is why not break the Commandments?

February 8th, 2009 at 11:58 am

Rules like these, I think are meant to be broken, if they can. They’re a challenge to creativity, or at least that’s how I’d take them if I were ever to write a piece of mystery fiction.

You’re absolutely right, though, in saying that as rules, they were meant to apply only to a certain restricted subset of crime fiction — the detective puzzler.

For proof, here are the opening paragraphs of Knox’s essay. (Follow the link in my review to read all of it.)

“What is a detective story? The title must not be applied indiscriminately to all romances in which a detective, whether professional or amateur, plays a leading part. You might write a novel the hero of which was a professional detective, who did not get on with his wife, and therefore ran away with somebody else’s in chapter 58, as is the wont of heroes in modern novels. That would not be a detective story. A detective story must have as its main interest the unravelling of a mystery; a mystery whose elements are clearly presented to the reader at an early stage in the proceedings, and whose nature is such as to arouse curiosity, a curiosity which is gratified at the end.

“And here, for my own part, I would draw a very clear line of demarcation between detective stories and ‘shockers’. Shockers are not in the true sense mystery stories at all; they do not arouse a human instinct of curiosity….”

— Steve

February 8th, 2009 at 6:43 pm

I think Knox’s “rules” are perfectly reasonable (the Chinaman one was a jab at the Fu Manchu nonsense); it’s some of Wright’s (SS Van Dine) that go rather overboard.

February 8th, 2009 at 9:13 pm

Curt —

Restricted to the subgenre of detective puzzlers, there’s no doubt that the rules are reasonable. My thought is that if the author is clever enough, that maybe the rules could be stretched or bent if never quite broken.

Here, from http://gaslight.mtroyal.ca/vandine.htm is a shortened version of Van Dine’s 20 Rules. As you can see, there’s a big overlap with those of Knox’s, and I can see a lot of flexibility and leeway in those of Van Dine’s that Knox doesn’t include. In fact, I have read a Golden Age mystery novel recently in which one of Van Dine’s rules is specifically broken.

To no ill effect, I may add.

— Steve

1. The reader must have equal opportunity with the detective for solving the mystery.

2. No willful tricks or deceptions may be placed on the reader other than those played legitimately by the criminal on the detective himself.

3. There must be no love interest. The business in hand is to bring a criminal to the bar of justice, not to bring a lovelorn couple to the hymeneal altar.

4. The detective himself, or one of the official investigators, should never turn out to be the culprit.

5. The culprit must be determined by logical deductions — not by accident or coincidence or unmotivated confession.

6. The detective novel must have a detective in it; and a detective is not a detective unless he detects.

7. There simply must be a corpse in a detective novel, and the deader the corpse the better. No lesser crime than murder will suffice.

8. The problem of the crime must he solved by strictly naturalistic means.

9. There must be but one detective — that is, but one protagonist of deduction — one deus ex machina.

10. The culprit must turn out to be a person who has played a more or less prominent part in the story.

11. A servant must not be chosen by the author as the culprit.

12. There must be but one culprit, no matter how many murders are committed.

13. Secret societies, camorras, mafias, et al., have no place in a detective story.

14. The method of murder, and the means of detecting it, must be be rational and scientific.

15. The truth of the problem must at all times be apparent — provided the reader is shrewd enough to see it.

16. A detective novel should contain no long descriptive passages, no literary dallying with side-issues, no subtly worked-out character analyses, no “atmospheric” preoccupations.

17. A professional criminal must never be shouldered with the guilt of a crime in a detective story. Crimes by housebreakers and bandits are the province of the police departments — not of authors and brilliant amateur detectives.

18. A crime in a detective story must never turn out to be an accident or a suicide.

19. The motives for all crimes in detective stories should be personal. International plottings and war politics belong in a different category of fiction.

20. And (to give my Credo an even score of items) I herewith list a few of the devices which no self-respecting detective story writer will now avail himself of. They have been employed too often, and are familiar to all true lovers of literary crime. To use them is a confession of the author’s ineptitude and lack of originality. (a) Determining the identity of the culprit by comparing the butt of a cigarette left at the scene of the crime with the brand smoked by a suspect. (b) The bogus spiritualistic se’ance to frighten the culprit into giving himself away. (c) Forged fingerprints. (d) The dummy-figure alibi. (e) The dog that does not bark and thereby reveals the fact that the intruder is familiar. (f)The final pinning of the crime on a twin, or a relative who looks exactly like the suspected, but innocent, person. (g) The hypodermic syringe and the knockout drops. (h) The commission of the murder in a locked room after the police have actually broken in. (i) The word association test for guilt. (j) The cipher, or code letter, which is eventually unraveled by the sleuth.

February 9th, 2009 at 12:58 am

Rules against “love interest” and “atmospheric writing” strike at the heart of the crime novel idea, in a shortsighed way I think. The implication that a servant, as a person not “worthwhile,” cannot be the culprit is based on snobbish and false assumptions.

Rules made to ensure “fair play” and to segregate the “thriller” from the detective novel are perfectly sensible.

And, yes, Rules were broken in the Golden Age, even by supposedly orthodox authors.

February 9th, 2009 at 6:32 am

Give me a “shocker” anytime over these guys…

February 9th, 2009 at 10:53 am

Aw, Juri. You don’t know what you’re missing. I can read and enjoy thrillers and shockers as much as you, and I do all the time. But give me an old-fashioned detective puzzler with clues, false leads and surprise endings, and I’m happy as a clam.

There’s nothing quite like the game of wits between author and reader — and it can happen in thrillers, too.

— Steve

PS. I’d just posted this comment and was looking it over when I spotted a word I’d used: old-fashioned. Trends come and go, I know, but I have a feeling that the popularity of “old-fashioned” detective story is similar to that of the LP as a means of supplying music. Never quite going away, with a small cult of enthusiasts keeping it alive and with resurgences from time to time, but it’s never going to be on top again.

February 9th, 2009 at 11:22 am

Doesn’t just suit me. I was once an avid reader of Christie (as a teenager), but she failed to interest me when I tried again some 15 years ago. I’ve read one book by S.S. Van Dine and remember being bored (even though I don’t remember much about the actual book).

February 9th, 2009 at 11:39 am

Juri

I’ll take it back, then. You DO know what you’re missing. I wouldn’t recommend Philo Vance and S. S. Van Dine to any new reader of mystery fiction, but if Agatha Christie’s not your cup of tea now either, then I’m not sure who to suggest. John Dickson Carr?

Or let’s turn things around. In terms of thrillers and shockers, of authors active in the 1920s and 30s, have you ever tried Edgar Wallace?

— Steve

February 9th, 2009 at 3:28 pm

Steve:

S. S. Van Dine must be spinning in his grave on a continual basis these days. Some of the same hoary gimmicks are being used on televised detective/crime fiction shows. To wit:

Relative to his 20th rule:

* “The bogus spiritualistic seance to frighten the culprit into giving himself away”: Agatha Christie herself unabashedly used this one in one of her Poirots (filmed in the ’80s).

* “The final pinning of the crime on a twin, or a relative who looks exactly like the suspected, but innocent, person”: This one was used just last week in a MONK episode.

* “The commission of the murder in a locked room after the police have actually broken in”: Used in an episode of JONATHAN CREEK; the killer was with the police.

Relative to his 1st rule:

* “The reader must have equal opportunity with the detective for solving the mystery”: This is the bedrock rule which should NEVER be violated by detective story writers, but which is constantly ignored, particularly on TV: I don’t know how many times the viewer was cheated out of this “equal opportunity” on MURDER, SHE WROTE and other programs. Only Jim Hutton’s ELLERY QUEEN seemed interested in giving us a sporting chance.

As to Van Dine’s 11th rule:

* “A servant must not be chosen by the author as the culprit”: That dodge had probably been done to death by the ’20s; even Conan Doyle used it at least once (“The Musgrave Ritual”) in the previous century.

As for his 17th rule:

* “A professional criminal must never be shouldered with the guilt of a crime in a detective story”: Once again, Conan Doyle’s Professor Moriarty comes to mind.

If there is one field of literature that characteristically goes against the grain of dumbing down the material for mass consumption, it’s the well-plotted DETECTIVE STORY, as defined by S. S. Van Dine. I applaud him for his efforts to bring logic and order to the mystery.

Mike

February 9th, 2009 at 7:42 pm

I noticed they used a seance in the TV adaptation of Peril at End House. Did Christie actually use this in the book? Remember, the medium in the TV Peril was Miss Lemon and there was no Miss Lemon in that novel! I thought the whole sequence was made up by the TV writers.

It is funny to see these same cliches still popping up today.

Nicholas Blake also might be worth trying if you don’t like Christie.

February 10th, 2009 at 3:14 am

I may try John Dickson Carr and Nicholas Blake one of these days. (Actually it seems more like “one of these years”, since my to-be-read pile is really a whole library.) From the Golden Age writers, I think my top choice would be Francis Iles.

I remembered one more from my growing years: E.C. Bentley’s TRENT’S LAST CASE. Couldn’t’ve cared less. (I even tried a Catherine Aird, since she was compared to Christie in a back cover, which shows just how great Christie was in the genre. [I know that Aird is a more recent writer.])

As for Edgar Wallace, him I haven’t tried, save for occasional short story.

February 11th, 2009 at 9:31 pm

You can polish off Francis Iles quite quickly. If it’s primarily criminal psychology/suspense that interests you, naturally you would find Golden Age “rules” of puzzle construction irrelevant. I think you might find Iles on the underwhelming side too. Maybe you should try Philip Macdonald’s Murder Gone Mad.

February 12th, 2009 at 5:22 am

Steve, I’ve read two books by Iles and I liked them both (MALICE AFTERTHOUGHT and another one whose name I can’t remember. It was some 15-20 years ago, though, so I don’t know what I’d think of them now. (I’m not sure if I have them at the moment.)

And yes, you’re right about the rules. The puzzles seem totally irrelevant and absurd. (Even saying this I acknowledge the absurdity of a Fredric Brown or a John Franklin Bardin. But at least in the case of Brown, he’s writing about real people whose feelings I can recognize. It’s been a bit too long since I read Bardin, so can’t really say about thim.)

Philip Macdonald has only one book translated in Finnish, THE LIST OF ADRIAN MESSENGER. Any reason I should try it?

February 24th, 2009 at 3:39 am

A few notes on various topics.

While I’m a big fan of S.S. Van Dine and Philo Vance, even his greatest defender has to admit that Ogden Nash had a point (“Philo Vance needs a kick in the pants”), and the later books can be formulaic — especially when you realise the murderer invaribly shows up on the same page in virtually every book. In the Vance tradition you have the early Ellery Queen’s and the unjustly forgotten Thatcher Colt books by A. Abbot(bestselling writer Fulton Oursler). Colt was loosely based on Teddy Roosevelt, and like TR was the Commissioner of the New York Police. The books are clever and fun in the classical mode, and perhaps a bit better written in strictly literary terms than most. Adolph Menjou played Colt in at least one movie, and Sidney Blackmer in another, both good casting since Colt was both a clothes horse and based on TR who Blackmer often played in films. Most of the books have the title, About the Murder of …, though two later books were called The Shudders and The Creeps.

If you like Francis Isles, and you are looking for classical mysteries from the period then check out his other well known pseudonym Anthony Berkley. The Poisoned Chocolates Case is a masterpiece featuring his series sleuth Roger Sherringham, and Trial and Error a classic non series murder tale adapted for televison for Alfred Hitchcock (I think starring Tom Ewell and one of the ones Hitch actually directed). If you still prefer the Isles sytle you might check out F. Tennyson Jesse’s A Pin to See the Peepshow or one of Hugh walpole’s ‘shockers’ like The Killer and the Slain and Portrait of the Man with Red Hair, but you probably aren’t going to find much in the classical line to your taste, though there are non series books by Christie, Nicholas Blake, Michael Innes, and Philip Macdonald you might enjoy. Macdonald in particular wrote the classic ‘shockers’ Mystery of the Dead Police and Murder Gone Mad as well as being a notable screenwriter on everything from Charlie Chan and Mr. Moto to Hitchcock’s Rebbeca.

As to whether to read The List of Adrian Messenger by Macdonald, I would say yes, by all means. Besides being the basis of an entertaining ‘gimmick’ film by John Huston, the books is a tour de force, as Macdonald’s series sleuth Anthony Gethyrn pursues a killer whose victims number in the hundreds and across a period of fifteen years. The film and book are close enough to enjoy both, but diverge at the ending for equally enjoyable climaxes. Macdonald was one of the few classical detective story writers to combine the elements of the ‘shocker’ in his detective novels, notably in Warrant for X (aka The Nursemaid Who Disappeared). Some don’t care for this, but it makes for more suspense than just who-dun-it. Warrant was also a notable film as Henry Hathaway’s 23 Paces to Baker Street (filmed before in England under the British Nursemaid title). Macdonald is more cinematic than many of his contemporaries and not afraid of a little melodrama.

And if Chistie isn’t your cuppa you might try Dorothy L. Sayers whose Lord Peter is a bit more literary or Margery Allingham whose Albert Campion often uses thriller elements to alieviate the tec puzzle. Just in general though it isn’t until well into the forties that the ‘shocker’ and the classical tale begin to come together. Michael Innes in particular did several books in the Buchan tradition, some with his series hero Sir John Appleby. Of later writers I would suggest Edmund Crispin’s often surreal comic Gervase Fen novels about an Oxford don who has a way with murder. The Moving Toyshop is exceptional with a nice impossible crime, and some of the books have an inside look at the British film industry since Crispin was conductor and composer Robert Montgomery who among other things wrote the scores for the Carry On films.

However, if your standard is ‘real people’ you probably should stick to suspense along the line of Isles. He’s a pretty high standard, but you might try Cornell Woolrich, Charlotte Armstrong, Margaret Millar, Elizabeth Saxnay Holding, Dorothy B. Hughes, Helen McCloy, and Helen Nielson. The classical tec story may just not be for you. If you enjoy Fred Brown you might look at some of the screwball school of the hardboiled genre like Jonathan Latimer’s Bill Crane books, Geoffrey Homes, Norbert Davis, and Erle Stanley Gardner’s Donald Lam and Bertha Cool mysteries. Or Craig Rice, Richard and Frances Lockridge’s Mr. and Mrs. North, Kelly Roos Jeff and Halia Troy, or Q. Patrick’s Peter and Iris Duluth who mix elements of suspense comedy and even classical detection.

The artificial pleasures of the classical detective story aren’t for everyone, but for those of us who enjoy the game half the fun is seeing how well the game is played — though both Agatha Chistie and Ellery Queen didn’t mind bending and breaking the rules, and John Dickson Carr danced all around them. Some sticklers have never forgiven Christie for Roger Ackroyd. Still, for the best writers in the genre they rules were just one more element of the game. I would point out that while the rules were certainly aimed at Sax Rohmer and Fu Manchu (the business of the Chinese and poisons unknown to science), they were equally aimed at popular writers such as Arthur B. Reeve whose Craig Kennedy encountered a good deal of sheer melodrama.

February 26th, 2009 at 12:03 am

A quick addenda, I should have mentioned that Francis Isles/Anthony Berkley was Anthony Berkley Cox a founding member of the Detection Club and contirbutor to some of their round robin novels as well. Some, myself included, consider his amateur sleuth Roger Sherringham to be the single most annoying and obnoxious sleuth in genre history — which be all accounts is what the author intended. Both Trial and Error and The Poisoned Chocolates Case have been reprinted fairly frequently so shouldn’t be too hard to find, but if you didn’t like Trent’s Last Case you are unlikely to care for rhe Berkley novels.

December 11th, 2010 at 4:23 pm

[…] Comment: In my review of Knox’s The Three Taps earlier on this blog, I included for easy reference his “Ten […]

January 7th, 2013 at 5:56 pm

I enjoyed the three taps and the insight it provides into life in an English village ninety years ago. However if Knox or Christie do not float your boat why not try Austen Freeman. His Dr Thorndyke is a pioneer of forensics and medical jurisprudence and you will learn some really useful techniques in crime solving as well as enjoying an excellently written whodunit.