Sun 19 Apr 2009

A Review by David L. Vineyard: E. C. BENTLEY – Elephant’s Work.

Posted by Steve under Authors , Reviews1 Comment

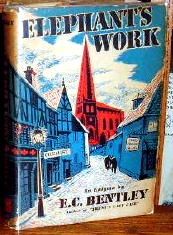

E. C. BENTLEY – Elephant’s Work: An Enigma. Hodder & Stoughton, UK, hardcover, 1950. Alfred A. Knopf, US, hardcover. 1950. Also published as The Chill. Dell 704, paperback, 1953.

E(dmund) C(lerihew) Bentley is one of the magical names in the mystery genre. His book Trent’s Last Case (1912) is usually cited as the birth of the Golden Age of the British detective novel, and certainly the book that carried the genre from the short form practiced by Doyle, Chesterton, and Morrison, to the novels championed by Christie, Sayers, Berkley and others.

In addition to the classic Trent’s Last Case Bentley also wrote a collection of short stories featuring journalist and amateur sleuth Philip Trent, Trent Intervenes (1938), and a second novel, Trent’s Own Case (1936) with H. Warner Allen, but then was silent in the field until 1950 when he penned Elephant’s Work: An Enigma.

And enigma is exactly what Elephant’s Work is. Bentley dedicated the work to John Buchan, and it is certainly in the form of a “shocker,” inspired when Bentley expressed his admiration for Buchan’s The Thirty Nine Steps and Buchan suggested Bentley pen his own. The result forty years later was this book. In retrospect he should have ignored the advice and stuck to detective stories.

The novel begins promisingly. The hero Severn boards a train where he encounters a formidable American and learns there is a dangerous fugitive abroad. As they wait, there is a ruckus coming from a nearby circus train. An elephant has escaped and gone on a rampage. When the elephant goes wild again on the train and causes a wreck, Severn is knocked unconscious.

When he awakens, he is suffering from amnesia and finds he is the guest of one General da Costa who informs him the name on his passport is Taylor, and while the General, the doctor, and everyone else are all perfectly kind, it soon dawns on Severn he is a virtual prisoner, and his fate is involved with someone known as Nick the Chill who works for a gangster called Farewell Billy.

In fact it is more than implied by the General and others that Severn is none other than Nick the Chill, a gunman in the employ of Farewell Billy.

So far so good. The writing is clean and clear and the suspense well calculated. The sense of mystery and Severn/Taylor’s confusion and growing paranoia well drawn. Is he the deadly Chill, or an innocent man being set up to take the fall in some elaborate scheme? Buchan himself could hardly have done it better, especially when Severn/Taylor eludes his protectors and tries to piece the mystery together pursued by mysterious sinister men and unable to go to the police who may believe he is a dangerous killer.

And then Elephant’s Work takes the most absurd twist you can imagine. I almost hesitate to reveal it, save unwary readers might think Elephant’s Work was a lost classic of the thriller genre only to run aground on the most unlikely reef in the history of the chase and pursuit novel.

Severn isn’t Taylor, and he isn’t Nick the Chill, he’s the Bishop of Glanister, on a little holiday before taking up his new duties — as the just appointed Archbishop of Canterbury — and the entire conspiracy has been the hastily contrived work of his friends attempting to protect him from any potential bad publicity while he was recovering his memory.

If at this point you feel the need to throw the book across the room, it is at least a small volume. Of course there is a bit more to it than that. The General himself was a fugitive of sorts who didn’t want Severn’s presence to reveal where he was until his situation was settled, but even that is hardly a satisfying explanation why everyone behaves in the most absurd manner possible and for the most absurd of reasons.

Ultimately Elephant’s Work is one of those annoying books where if anyone behaved halfway reasonably or made some effort to actually think, the entire facade would come crashing down like the house of cards the author has constructed. You should on general principle avoid any book which the author subtitles an “Enigma.” Chances are he means it.

This shouldn’t put anyone off reading Bentley’s classic detective novels. While it’s a bit dated, Trent’s Last Case is a genuine classic, and both Trent Intervenes and Trent’s Own Case are exceptional works in the genre.

Philip Trent is the model for many of the amateur sleuths to come later and especially an early influence on Dorothy L. Sayers and Lord Peter Wimsey. Bentley was a clever and charming man who gave his own name to the playful four line stanzas known as Clerihews he wrote in school and which were published with illustrations by G.K. Chesterton as Biography For Beginners. Bentley himself was a respected journalist and editorial writer for the Daily Telegraph.

But be forewarned, Elephant’s Work is one of the single most annoying thrillers ever written, light as a souffle only because it really is filled with hot air. And be careful where you throw it. You might upset an elephant and start the whole absurd business all over again.

The victim of Trent’s Last Case is the millionaire Sigsbe Manderson, that name being a motive for murder if nothing else, as some wag once pointed out. Trent’s Last Case was filmed twice, the second time as The Woman in Black with Michael Wilding as Trent and Orson Welles as Manderson.

Despite, or because of that, it’s a dull affair all around. Luckily we were spared the film version of Elephant’s Work — one of those small mercies we should be grateful for.

June 13th, 2021 at 3:23 am

[…] Father Brown (or Leo Bruce’s parody) would have blandly said: ‘I told you so’ – and that David L. Vineyard flung the book across the […]