Sun 10 Jul 2011

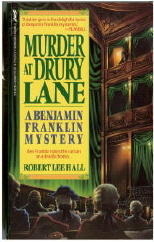

Archived Review: ROBERT LEE HALL – Murder on Drury Lane.

Posted by Steve under Authors , Bibliographies, Lists & Checklists , Reviews[3] Comments

ROBERT LEE HALL – Murder on Drury Lane. St. Martin’s, paperback reprint; October 1993. Hardcover edition: St. Martin’s, November 1992.

Checking back over Hall’s career, he seems to have worked exclusively in the historical mystery subgenre. In doing so, he has also been no slouch in choosing either his characters or the period settings he’s put them in. Here’s what I found, in terms of his crime-oriented fiction:

Exit Sherlock Holmes. Scribner’s, hc, 1977. Playboy Press, pb, 1979.

The King Edward Plot. McGraw-Hill, hc, 1980. Critics Choice, pb, 1987.

* Benjamin Franklin Takes the Case. St. Martin’s, hc, 1988; pb, 1993.

Murder at San Simeon. St. Martin’s, hc, 1988. No paperback edition.

* Benjamin Franklin and a Case of Christmas Murder. St. Martin’s, hc, 1991; pb, 1992.

* Murder on Drury Lane. St. Martin’s, hc, 1992, pb, 1993

* Benjamin Franklin and the Case of the Artful Murder. St. Martin’s, hc, 1994; pb, 1995.

* Murder by the Waters. St. Martin’s, hc, 1995; trade pb, 2001.

* London Blood. St. Martin’s, hc, 1997. No paperback edition.

The Ben Franklin cases of detection, of which Murder on Drury Lane is one, are marked with an asterisk. Sherlock Holmes made an appearance in Hall’s first mystery only. Murder at San Simeon takes place at the California mansion of William Randolph Hearst, with Marion Davies, Louella Parsons, Jean Harlow and Charlie Chaplin all making at least cameo appearances.

That leaves The King Edward Plot, which takes place in England in 1906, during the reign of Edward VII, and one online source describes it as “the first novel-length story to feature Holmes as a character.†This does not appear to be so. Holmes’s appearance is not mentioned in a Kirkus review of the book, and the statement seems in itself to contradict the existence of Exit Sherlock Holmes.

Other mystery novels that Holmes had a role in and which also came before Hall’s first book are:

Ellery Queen [Paul W. Fairman], A Study in Terror, Lancer, 1966.

Michael & Mollie Hardwick, The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes, Mayflower (UK), 1970.

Nicholas Meyer, The Seven-Per-Cent Solution, Dutton, 1974.

Philip José Farmer, The Adventure of the Peerless Peer, Aspen, 1974.

Don R. Bensen, Sherlock Holmes in New York, Ballantine, 1976.

Richard L. Boyer, The Giant Rat of Sumatra, Warner, 1976.

Nicholas Meyer, The West End Horror, Dutton, 1976.

Austin Mitchelson & Nicholas Utechin, The Earthquake Machine, Belmont, 1976

– Hellbirds, Belmont, 1976.

I may have missed one or two, but I don’t believe many more than that. Keep in mind that this is a list of novels only, and that I deliberately attempted to avoid self-published works. Ever since 1977 (what happened then, timewise?) the dam has burst, and Sherlock Holmes has unquestionably become the one single fictional character, detective genre or not, who has appeared in the works of more novels by other authors than any other. (You can question the statement, if you like, as long as you can come up with an alternative.)

I seem to have gone off on a tangent here. The Sherlockian connection that exists in The King Edward Plot, and there is one, is that two of the four amateur detectives who uncover the plot reside at 221A Baker Street. One of them nicknamed “Wiggins.†I will have to read it.

Mr. Benjamin Franklin is getting restless, I am sorry to say. The book I have just read is about him, and he is being neglected. Here is a quote from page two. Franklin’s son William, a law student while in London, has just walked into the home where the Franklin entourage is staying, but he is unable to talk about the experience he has just had:

“Desdemona,†breathed William Franklin. “She played Desdemona.†He blinked, as if waking. “But, Father, I did not tell you that I went to the theatre. Indeed I have not been in my chamber since midmorning.â€

If Mr. Franklin’s explanation behind his deductive reasoning processes does not match that of the master, the attempt is well taken, at least by me, and the language is well appropriate for the tale that follows. Telling the story is Nick Handy, a twelve-year old lad who is Mr. Franklin’s illegitimate son. (Franklin made more than one trip to London, and there is a story behind this, one that was told in the first installment of the series. See above.)

To tell you the truth, the language, the vocabulary and the insight of the narrator is far beyond those of a twelve-year-old boy, but if you assume that Nick is rather precocious and add some sense of wonder, you will soon not notice.

The year, lest I forget to mention it, is 1758, and Drury Lane (as the title aptly suggests) is the center of the mysterious misadventures taking place. David Garrick hires Ben Franklin to investigate, who obligingly allows young Nick to tag along, making sketches of the various places they go and the people they meet.

It also turns out that Mr. Franklin is a pioneer in the field of fingerprints and handwriting analysis, but it is the later – with regard to the threatening notes that Garrick has been receiving – that is the more important of the two this time around.

The pace of the tale is leisurely, to say the least. Perhaps more important to the mystery, until the end, of course, are the sights and sounds of the theater itself, as well as the area and people around it, bit players included. Other famous personages have roles as well: Sir John Fielding, Dr. Samuel Johnson. Horace Walpole attends a play, as does Tobias Smollett.

A well-manufactured atmosphere has been created here, in other words, with a melodramatic ending that fits the mood perfectly. If the detection takes second place, it is only a minor quibble on my part to say so.

July 11th, 2011 at 4:58 pm

SHERLOCK HOLMES BRIDGE DETECTIVE RETURNS – it is not a novel, it is a bridge instruction book with Sherlock Holmes short stories intermingled

July 11th, 2011 at 6:49 pm

Jamie, Thanks for catching that. I didn’t realize it when the I originally wrote the review, but I have a copy of the book now, and you’re quite right.

I think what I will do is delete it from the list of Holmes pastiches in the review, and let anyone reading this later figure out what happened…!

— Steve

January 14th, 2015 at 1:48 pm

I’ve read Hall’s “Exit Sherlock Holmes” and found it surprisingly, abysmal. A real letdown. Main problem: it was mawkish, maudlin, lachrymose..huge gobs of sentiment and hand-wringing emotion at the end of the tale. Totally dismaying.

What I really was hoping was that Hall had written a story which posited that Holmes was actually an android from the future, sent back in time to the Victorian era–and that this accounts for his phenomenal powers of analysis and reason. A computer brain. I thought it was going to be a combination Holmes mystery and innovative SF tale, in which Holmes’ android programming breaks down in some way–placing him in real danger–and thus, Watson, while treating him–gradually uncovers the true mechanical physiognomy of his friend. I figured that from that point in this (imaginary story I had concocted in my mind), Watson must mentally adjust to the revelation, and then keep Holmes’ otherworldly aspects, a secret as well. In the best tradition of sidekick loyalty. That would have been astounding, amazing, grand! But that is not what I found.