Sun 19 Jul 2009

Reviewed by Marvin Lachman: PATRICK QUENTIN – A Puzzle for Fools.

Posted by Steve under Reviews[8] Comments

by Marvin Lachman

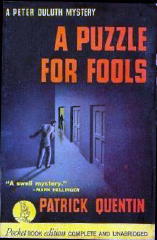

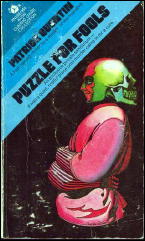

PATRICK QUENTIN – A Puzzle for Fools.

Simon & Schuster, US, hardcover, 1936. Victor Gollancz, UK, hc, 1936. Paperback reprints include: Pocket #83, 1940, with several later printings; Dell D192, Great Mystery Library #4, 1957; Ballantine F461, 1963; Avon PN238, 1969, with at least one later printing. Trade paperback: Penguin Classic Crime, 1986.

During the nineteen-thirties many movie comedies had the hero and heroine meet “cute.” Example: Claudette Colbert and Gary Cooper meeting in a haberdashery; he only wants pajama bottoms, and she only wants pajama tops. They agree to buy a single pair.

Patrick Quentin’s A Puzzle for Fools is in that tradition, as Peter Duluth, an alcoholic theatrical producer, and Iris Pattison, a young woman suffering from melancholia, met at an exclusive mental sanatorium. This book has seldom been out of print since it was first published more than fifty years ago.

The Duluth books were to get better as time went on. This book, the first which Hugh C. Wheeler and Richard Wilson Webb wrote as Patrick Quentin, is lively and readable but shows some of the earmarks of inexperience (Wheeler was only twenty-four at the time) and hasty writing; the team was very prolific in the years before World War II.

Duluth’s fears as he goes through alcohol withdrawal while trying to solve a murder are not well conveyed. Instead, we have him saying things like, “Those were some of the most harrowing moments of my life,” but the authors do not make the readers feel it.

Too often the authors rely on Had-I-But-Known writing to get across that there are sinister events to come. For example: “Of course, I had no idea then of the fantastic and horrible things which were soon to happen in Doctor Lenz’s sanatorium. I had no means of telling just how significant these minor and seemingly pointless disturbances were.”

And, later, “Maybe I could have prevented a lot of tragedy if I had gone to the authorities there and then.” (Quentin comes close to setting a world’s record for the amount of information withheld from the police in this book.)

The pace is very quick, and Duluth’s light, self-deprecating tone makes him an enjoyable narrator. Don’t expect the kind of sophistication to be found in the British puzzles of the nineteen-thirties, though Wheeler and Webb were born in England.

No American writer has quite achieved what is to be found in Allingham, Innes, Blake, Sayers, et al. There must be an invisible barrier on the western shore of the Atlantic.

Incidentally, if the name Hugh Wheeler sounds familiar, it should. After he stopped writing mysteries in 1965 he became a major playwright, best known for his collaborations with Stephen Sondheim on such works as A Little Night Music, Pacific Overtures, and Sweeney Todd.

Editorial Comment: This is the second of two mysteries taking place in psychiatric institutions that Marv referred to in his recent review of A Mind to Murder, by P. D. James. Although the book was in print in 1987, it no longer seems to be, some 22 years later.

Coming Soon: Another review of this book by Newell Dunlap and Marcia Muller, taken from 1001 Midnights; then my review of Puzzle for Players, the second book in the series.

Also relevant: Kevin Killian’s review of The Crippled Muse (1951), by Hugh Wheeler; and two of my previously posted reviews. First, Death My Darling Daughters, by Jonathan Stagge; then Return to the Scene, by Q. Patrick.

July 20th, 2009 at 12:45 pm

The Duluth’s made it to the screen in The Black Widow as Van Heflin and Gene Tierney, in The Female Fiends (Strange Awakening) based on Puzzle for Fiends as Lex Barker and Monica Grey (called Peter and Iris Chance), and in Homicide for Three based on Puzzle for Puppets played by Warren Douglas and Audrey Long.

I always liked the Duluth books as one of the better Nick and Nora clones and the authors made good use of their own theatrical backgrounds in the series.

July 20th, 2009 at 2:00 pm

“No American writer has quite achieved what is to be found in Allingham, Innes, Blake, Sayers, et al. There must be an invisible barrier on the western shore of the Atlantic.”

British authors do British mysteries.

American authors do American mysteries.

I don’t think the Quentins, at least in this incarnation, ever tried to be like Allingham or Innes. The Puzzle series is quintessentially American even though both Webb and Wheeler were born in Albion, and I tend to agree with the late French mystery critic Maurice-Bernard Endrèbe that they were a gasp of fresh air at the time and a significant milestone in the transition from the Golden Age detective story to the Post-War suspense novel. I may blog about this when my writer’s block is over.

July 20th, 2009 at 3:07 pm

Endrèbe said the Quentins were “a significant milestone in the transition from the Golden Age detective story to the Post-War suspense novel.”

That’s a fascinating observation, and one I both immediately agree with and will have to keep in mind as I make my way (very slowly) through their work.

I say slowly, not for lack of appreciation, but for lack of time. There are too many other books in my basement and garage calling my name.

But every book I’ve read by them, in any of their incarnations, has had something special about it to remember it by.

And yet, in spite of Marv’s comment that A PUZZLE FOR FOOLS was still in print in 1987, the Quentin novels are unknown to all but a very small handful of readers today.

July 20th, 2009 at 5:09 pm

The Quentin books are due a revival and it would be as well to start with the Duluth books which are among the best of their kind — smart, funny, and filled with good characters and solid mystery plots.

One correction, in 1987 the Duluth books weren’t “still in print,” but “back in print.” The former suggests a writer like Christie who has never been out of print, which isn’t true of the the Quentin titles. Still, back in print means they could be discovered again.

July 20th, 2009 at 6:19 pm

David

Yes, you’re right. What Marv said in 1987 was that it has “seldom been out of print,” and he was speaking only of A PUZZLE FOR FOOLS, not necessarily all of the Duluth books, or even the Puzzle series.

I wonder if the folks at Rue Morgue Press have considered any of the Quentin books for reprinting. Are there any other publishers doing what they are doing? (They do tend to go with lighter Golden Age material, but not exclusively.)

July 21st, 2009 at 9:43 am

When they made the film of BLACK WIDOW they changed the name of the character from Peter Duluth to Peter Denver. I guess they wanted a bigger city.

July 21st, 2009 at 9:55 am

Producers always go for the bigger names as drawing cards, don’t they?

And looking at the various pairings that were used in making “Duluth” movies — see Comment #1 — I think that Van Heflin and Gene Tierney in BLACK WIDOW beat any of the other choices, hands down.

July 21st, 2009 at 4:53 pm

[…] of author Patrick Quentin’s Peter Duluth mysteries, the first being Puzzle for Fools, reviewed here (by Marv Lachman) and in the post just preceding this one. There were nine books in the series in […]