Fri 4 Dec 2009

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

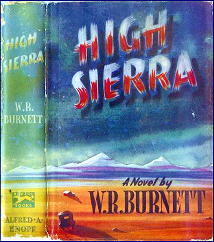

W. R. BURNETT – High Sierra. Alfred A. Knopf, hardcover, 1940. Paperback reprints include: Bantam #826, 1950; Carroll & Graf, December 1986; Zebra, November 1987.

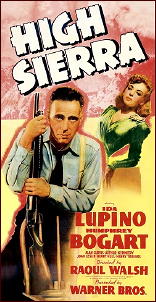

Films: Film: First National, 1941 (with Ida Lupino, Humphrey Bogart; director: Raoul Walsh). Also: Warner Bros., 1949, as Colorado Territory (with Joel McCrea, Virginia Mayo; director: Raoul Walsh). Also: Warner Bros., 1955, as I Died a Thousand Times (with Jack Palance, Shelley Winters; director: Stuart Heisler).

“Early in the twentieth century, when Roy Earle was a happy boy on an Indiana farm, he had no idea that at thirty-seven he’d be a pardoned ex-convict driving alone through the Nevada-California desert towards an ambiguous destiny in the Far West.”

Thus begins what is, in effect, the biography of Roy Earle, a fictional creation who reflects the lives of several eminent American outlaws of the 1920s and 1930s.

The structure and texture of the opening sentence signals the reader that this will be much more than simply a genre piece of tommy guns and molls. Burnett will attempt nothing less than a definitive appraisal of a bandit’s life as Earle leaves prison, falls in love, and works toward the robbery that will doom him.

For many, Sierra is probably more familiar as the finest of Bogart’s films (with the arguable exception of The Treasure of Sierra Madre). In the film version, John Huston sought to create a romance, a complex variation on the Robin Hood myth, but Burnett creates a novelistic portrait of Roy Earle that is full of fire and contradiction.

Chapter 37 is the key scene in the book. In the space of 3000 words, Roy Earle expounds on himself (?I steal and I admit it”); on his inability to trust (?The biggest rat we had in prison was a preacher who’d gypped his congregation out of the dough he was supposed to build a church with.”); and on the failure of the common man to fight for himself (?Why don’t all them people who haven’t got any dough get together and take the dough? It’s a cinch.”).

He is, throughout the novel, idealistic, naIve, ruthless, and doomed in a way that is almost lyrical. Not unlike Studs Lonigan, Roy Earle becomes sympathetic because his faults, for all their outsize proportion, are human and understandable, and his humility almost Christ-like. “Barmy used to talk to me about earthquakes,” Roy says; “he said the old earth just twitched its skin like a dog. We’re the fleas, I guess.”

Far from the myths created by J. Edgar Hoover’s biased attitude toward the criminals of the 1930s, Burnett gives us a sad, sometimes surreal look at a true outlaw. High Sierra is filled with every possible kind of feeling, from bleak humor to a pity that becomes Roy Earle’s doom.

The book’s theme of time and fate is worthy of Proust. If you want to know what made the work of “proletariat” America so powerful in the 1930s, all you have to do is pick up this novel.

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright ? 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

December 4th, 2009 at 10:18 pm

Great novel and great film (two good remakes too), but Burnett’s romanticized version of the outlaw is no more realistic than Hoover’s version. Roy Earle is certainly a sympathetic figure, but the real thing was often a charming sociopath (and not always charming) who didn’t really give a damn where the bullets struck or who got hurt.

Bonnie and Clyde were in reality a cheap prostitute and a homosexual psychopath, Machine Gun Kelly little more than a thug. Even Dillinger is less than the sum of his parts, Johnny Depp to one side.

My grandfather was a Deputy Sheriff in East Texas in the thirties and knew and even exchanged gunfire with some of these romantic outlaws. Some of them were perfectly charming people when they weren’t committing crimes, but when the time came not one of them gave a damn if a bystander ended up dead.

Like Jesse James and Billy the Kid you are better off with the legend than the murderous reality. High Sierra is a great novel and a great film, but it bears the same relation to reality that The Adventures of Robin Hood does to English history.

December 7th, 2009 at 6:52 am

Sorry, but I always found the film HIGH SIERRA kinda corny and overly-sentimental (unusual for Walsh). I much prefer Walsh’s bleak, exciting remake, COLORADO TERRITORY.

December 7th, 2009 at 10:02 pm

Dan

I like High Sierra better than you, but actually agree about Colorado Territory, it seems much closer to what Burnett was trying to say, and the western setting seems to give the film a depth the original lacks.

They made yet another of Burnett’s crime films into a western, with Delmer Daves’ The Badlanders based on Asphalt Jungle. In that case it isn’t as good as the original, but it is still a good film.