Tue 24 Jul 2012

A Movie Review by Walter Albert: LEMORA, LADY DRACULA (1973).

Posted by Steve under Horror movies , Reviews[6] Comments

by Walter Albert

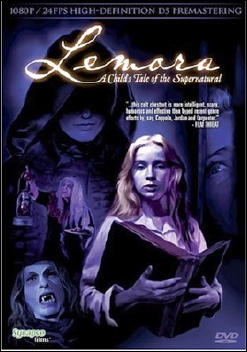

LEMORA, LADY DRACULA. Media Cinema Group, 1973. Originally released as Lemora: A Child’s Tale of the Supernatural. Lesley Gilb, Cheryl Smith, William Whitton, Hy Pyke, Maxine Ballantyne, Steve Johnson, Parker West. Director: Richard Blackburn, also co-screenwriter.

Now that I have disposed of the romantic and realistic Damsels in Distress (DID) films, honesty obliges me to admit that there is one kind of DID film that I find not unappealing  the bizarre or the erotic.

A late-night film I saw recently qualifies, on both counts. Lemora, Lady Dracula is described in John Stanley’s Creature Features Movie Guide (privately printed, 1981) as an “offbeat, surrealistic vampire flick with heavy artistic overtones,†a fairly accurate, bite-sized summary.

The basic narrative concerns an adolescent girl who has been redeemed by a fundamentalist congregation from her worthless parents and trained as a singer to witness for the church. When she receives word that her father is dying and would like to see her, she runs away, traveling through a nightmare country inhabited by prostitutes and lascivious rustics until she is waylaid and carried off by monstrous, semi-human creatures looking like rejects from Dr. Moreau’s laboratory.

Escaping from the stone prison they lock her into, she is “rescued†by a tall, beautiful woman dressed in black with thick white makeup and given a robe to put on for a mysterious ceremony. Both Lemora and the fey children who attend her are vampires, and the girl’s father has become one of the Moreau-like creatures who had kidnapped her. The rest of the film is taken up with the girl’s flight from Lemora and her cohorts and the vampire’s eventual victory.

The film’s colors are predominantly black and red with glossy highlights, and there is a veneer of seductiveness and erotic titillation in almost every frame. (Even in the opening sequences in the church, the girl is dominated by a young, intense minister of whom we are immediately suspicious.)

The depiction of the vampire children is particularly effective, a ‘blend of the diabolic’ and the pathetic. Lemora, who seems to be an untrained actress and reads her lines stagily (she is better at leering than reading) is the Dark Lady of romantic legend and exudes a sensual quality that gives the film a rather lurid cast.

There is increasingly less distinction between the present and past, fantasy and reality, and the girl’s flight from seduction becomes a sexual odyssey that is often quite disturbing.

Although Lemora is clearly an exploitation film and sometimes borders on the ludicrous, its implicit content pre-dates the recent rash of summer-camp psycho films but, like them, charts adolescents’ ambivalent sexual feelings.

The most common situation is one in which young girls or women are pursued by murderous/sexually threatening men or women. The ambivalence of the spectator’s feelings toward the monster in the classic horror film (both admiration and fear) is exploited in a more troubling way.

The classic film monster was often a tormented being with some impulse toward good; now, he  or she  is as threatening as the unspecified taboos and mysteries of sex, a disquieting visualization of the adolescents’ deepest fears and instincts.

Another feature of these films is that very often the monster is not exorcised or destroyed. He lives again to spread havoc through one or more sequels. This was also true of the Universal Studio horror cycle, but there was usually some escape from the threat posed by the monster.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yQNmu4Cw72s

In this open-ended narrative one can see a reflection of the contemporary fondness for unresolved plots. Like the anti-detective novel, where the narrative gaps are left unresolved, the conventions of the horror film seem increasingly to function not to quiet anxieties but to intensify them and may reflect a fairly general feeling that there are no longer satisfactory solutions to any problems.

It may be a symptom of the disappearance of some of the traditional distinctions between elitist and popular art that popular art can feed contemporary anxieties, but that phenomenon, in itself, may be as disquieting as the fears it no longer mediates but intensifies.

Vol. 7, No. 2, March-April 1983 (slightly revised).

July 24th, 2012 at 6:51 pm

Hmmm.. sounds like a classic .

The Doc

July 24th, 2012 at 8:32 pm

Based on that first video clip, the bus ride into hell, I’d have to agree with you, Doc. I don’t get chills too often watching movies, but this one’s a doozie.

July 25th, 2012 at 9:36 am

DO see it on the restored DVD. I wish they would release a Bluray version.

July 25th, 2012 at 10:08 am

Tim

Yes, that’s the DVD I’ve just purchased. The restoration has gotten rave reviews, and the are a number of extras, including a commentary track with Leslie Gilb (Lemora), director Richard Blackburn and producer Robert Fern.

Unfortunately Cheryl “Rainbeaux” Smith, who played Lila, ran into trouble with drugs, served a couple of terms in prison, and died in 2002 at the age of 47. From the little I’ve read about her, she might have had a fine career in the movies.

May 9th, 2013 at 8:58 am

One of the greatest vampire movies of the seventies, the Synapse dvd looks wonderful showing off Bava-esque blues and Argento-like reds! Man I would LOVE to see Synapse release it on Bluray!

May 10th, 2013 at 3:07 am

Great review, I enjoyed it. It’s actually one of the few vampire movies I enjoy (there’s been a few since the twilight rage… and don’t even let me get started on that one).