Sat 20 Mar 2010

A Movie Review by Walter Albert: DR. JEKYLL AND MR. HYDE (1931).

Posted by Steve under Horror movies , Reviews[16] Comments

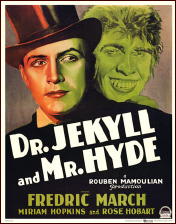

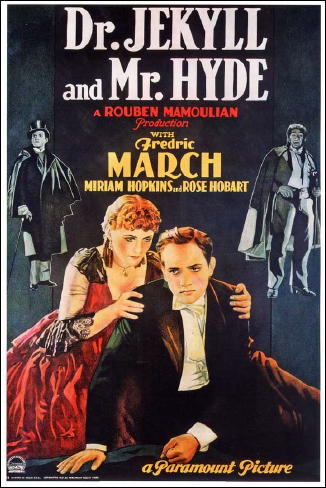

DR. JEKYLL AND MR. HYDE. Paramount Pictures, 1931. Fredric March, Miriam Hopkins, Rose Hobart, Holmes Herbert, Halliwell Hobbes, Edgar Norton, Tempe Pigott. Screenplay: Samuel Hoffenstein and Percy Heath, based on the story by Robert Louis Stevenson. Director: Rouben Mamoulian.

In 1931, two films were released that are still being shown in theaters and on television: James Whale’s Frankenstein and Tod Browning’s Dracula. Their great popularity initiated the horror cycle of the thirties.

A third film was released that year whose subject was, like Frankenstein, the creation by a brilliant, eccentric scientist of a creature who threatens his creator’s life and sanity, but Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde is director Rouben Mamoulian’s only horror film, and it has languished in relative obscurity,

The film’s fluid, imaginative camera work, for which Mamoulian was noted, allies it to the best horror/fantasy films of the period as well as to the innovative musicals that were Mamoulian’s chief subjects in his long Hollywood career. It may be of some interest to note, in this respect, Whale’s direction of the 1936 Showboat, and to suggest that in their free use of non-realistic elements, the musical and horror films of the thirties are not unrelated.

Mamoulian’s adaptation, like the other film versions of Robert L. Stevenson’s novella, places great emphasis on the laboratory and transformation scenes and, unlike the source, doesn’t attempt to conceal the nature of Hyde’s identity from the audience.

(In Stevenson’ s story, Hyde is the evasive criminal whose secret Mr. Utterworth, the lawyer-investigator wryly calling himself Mr. Seek, sets out to uncover, making of the adventure at once a morality and a detection tale.)

The laboratory is the conventional workshop of the thirties’ horror film, a classical locus that is at its most poetic and imaginative in Whale’s Bride of Frankenstein. It is also a dramatic stage which gives some slight plausibility to the drug-induced emergence of the Hyde personality.

Mamoulian’ s principal interest is probably not in the horrific or suspenseful elements of the story, although his film is lacking in neither of these. His Hyde — a curious Simian-Negroid creation that may strike some viewers as a rather blatant ethnic stereotype — is certainly repulsive enough, but I think the director’s real subject is the consequences of the release of all inhibitions, his Hyde brooking no interference with any of his immediate needs and desires.

This is most evident in the careful portrayal of the apparent distinction between Jekyll, the staid Victorian lover (even if unconventional scientist), and Hyde, the sensual, brutal lover whose pleasure is in a sadistic inflicting of pain on his mistress. And it is in the tactful but powerful depiction of Hyde’s relationship with his mistress (marvelously played by Miriam Hopkins) that the originality of this film in its relation to the horror film lies.

The male/female relationships in the Hollywood horror films of the period tended to be chaste, unlike the franker treatment in other genre films: the rampant visual/sexual puns in the Busby Berkeley musicals, the poetic physicality of the Tarzan/Jane relationship in the first two MGM Weismuller/O’Sullivan films and Kong’s famous — and later edited — undressing of Fay Wray in King Kong.

If one of the cherished memories — and cliches — of the monster chasing and sometimes carrying the heroine to a possible but never realized fate worse than death, the sexual play in these films is relatively tame.

Not so in Mamoulian’s Jekyll. One of the best sequences — still memorable and unsettling is of Hyde’s unexpected return to his mistress’s chambers and his subsequent vicious teasing before he strangles her in a grim and deadly parody of the sexual embrace.

It has often been said that the Horror of Dracula (Hammer Films, 1957) made explicit the eroticism of the vampire myth; what should also be pointed out — and perhaps for its irony — is that in the year that Browning’ s Dracula presented the classic version of the gentleman vampire, Mamoulian’s night-creature (like Dracula, freest and most powerful in his mistress’ s bedroom) tortured and teased and sexually abused his lover a way that the “mainstream” horror film would only dare to follow a quarter of a century later.

The classic horror film has its narrative source in Victorian taboos and the way in which they are circumvented by the monster created in the laboratory or the grave. The vampire is the dark lover, the sensual bringer of pleasure and death, so unlike the correct, cardboard hero.

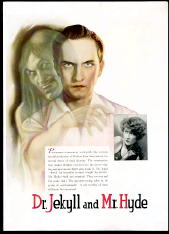

In Mamoulian’s film, the hero and the villain inhabit the same body. His Jekyll (Fredric March) has been criticized for his wooden playing, but what has not to my knowledge been pointed out is the way in which, as Hyde increases in strength, Jekyll comes to resemble him.

There is a striking scene when Jekyll returns home, free he thinks of Hyde but dressed in the cape and top-hat affected by his other self and in his extravagant gestures more like the exuberant Hyde than the controlled scientist.

But, then, Hyde was never far from Jekyll as the scientist pursued his obsession with the separation of the dual self, an obsession whose consequences are finally as destructive as Hyde’s natural genius for evil.

Early in the film, before Jekyll effects his first transformation, the good doctor treats a patient in her room. This patient is Ivy, the prostitute Hyde will pursue and kill, and as Jekyll takes his leave of her after they are surprised by his friend Lanyon in a passionate embrace, Ivy whispers seductively, “Come back,” and languorously, voluptuously moves her bare leg enticingly back and forth.

Mamoulian superimposes the shot of her leg and the echo of her invitation over the following scene as the supposedly blameless Jekyll and his friend walk away from the apartment. Sex and science are both seductive siren calls, and the breaching of limits is fatal for both scientist and lover.

Call Mamoulian’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde a morality play, a scientific romance, a monster film with many of the genre’s conventions, a psychological flirtation with the mysteries of the self, this superbly crafted and haunting film is an artful extension of the possibilities of the horror film, and it has a power to disturb that still sets it apart from most other genre films of its time.

March 21st, 2010 at 11:18 am

Hyde here is very close to the simian version suggested in Stevenson’s story, much more so than Barrymore or Tracy’s versions. Strictly from the basis of the story the Jack Palance is very good.

March, of course won the Oscar for this (as much the special effects as the acting) and Hopkins garnered great reviews. My uncle told me his parents, who were related to her and very religious, went to see the film because they had heard so much about it. They were horrified at her Ivy and never went to a movie again.

Walter

As you point out there is curious tie between horror and musicals from this period. It may be the artificial nature of both or the simplified story structure and visual emphasis, but it is clearly there.

And great job on a classic film too often left out when the great horror films are talked about. It’s a far better film than the over blown Tracy, though you have to miss the Freudian sequence of Lana Turner and Ingrid Bergman draped in flowing cloth (and nothing more) as Tracy drives them pulling his chariot with his whip.

March 21st, 2010 at 12:20 pm

It’s very much a Pre-Hayes Code movie, which is presumably why it gets away with some fairly kinky elements (see the Karloff/Lugosi THE BLACK CAT for a study in how to get away with sheer perversity in a mainstream Horror movie). This and the Tracy movie were really the only serious treatments of the story until after the war. You have to wonder whether Hollywood’s apparent disinclination had something to do with the strong sexual element in the story. Unlike DRACULA, there is no attempt to disguise them, and there is always a feeling that Hyde is at least partly sublimated Libido.

March 21st, 2010 at 1:34 pm

Stevenson claimed that the first version of the story, written after a nightmare, was so horrible that his wife persuaded him to burn it and write another. Of course that may have been a bit of self promotion, but the book certainly reads as if a dream inspired it, and hit a note that still resonates today.

The first stage production of the story in West London coincided with the Jack the Ripper murders (just barely), and ever since the two have been tied. American actor Richard Mansfield was so convincing as Hyde that he was briefly a suspect in the Ripper murders (along with several hundred others).

The best description of the story was the comment that it is the only mystery ever written where the solution is more horrible than the crime. Especially true as Stevenson is careful to never exactly say what Hyde’s crimes are.

The Victorians were both fascinated and horrified by atavism, the idea that man could become a throwback to his more primitive self. Conan Doyle used the theme in several of his stories and Wells in THE ISLAND OF DR. MOREAU, but no one as powerfully as Stevenson — who manages to suggest much more than he ever says, letting his readers fill in all the lurid details of Hyde’s trespasses.

Both the March and Tracy films are major productions with star casts and production values most horror films could only dream about. Neither Paramount or MGM did much horror, but here they both go full out.

Tracy didn’t care for his performance and admittedly he is badly cast in the film, but thanks to the dream-like quality and the heavy handed Freudian overtones as well as a splendid performance by Bergman in the Hopkins role the film is a pleasure to watch.

Barrymore did the transformation without make up or special effects in the silent version, and Tracy mixed that with special effects, but March’s version wins hands down for the transformation scenes, much of it done with the use of filters that revealed the face of Hyde without cutting away.

March 22nd, 2010 at 6:17 am

Wonderful review: scholarly but never ponderous, as usual for Walter.

Leonard Wolfe commented that the book is full of Victorian gentlemen running about lste at night on unspecified business. He also noted the prevalence of doors in the story and what they portend. “Doors keep secrets but they also reveal them; a book itself is a kind of door.”

March 22nd, 2010 at 9:26 am

Did anyone catch the recent showing of THE MAGICIAN(1926) on TCM recently? It had some early elements that were used in the first sound horror movies: the mad scientist, the crazy assistant, the isolated and spooky laboratory, the pretty girl who the mad scientist wants to operate on, etc. All the elements that we love.

March 22nd, 2010 at 10:38 am

Myself, I think March’s Hyde looks like Jerry Lewis!

March 22nd, 2010 at 3:54 pm

About time THE MAGICIAN was finally revived. For anyone who doesn’t know it is based on Somerset Maugham’s novel and the character of Oliver Haddo was based on the notorious Alister Crowley, self proclaimed mage, pervert, con-man, and also model for Dennis Wheatley’s Mocata in THE DEVIL RIDES OUT and Ian Fleming’s Ernst Stavro Blofield.

Now if someone will just find the lost serial HOMUNCULUS with Otto Fons my silent wish list will be greatly thinned down.

Ray

He does look a bit like Jerry, but then so does Henry Hull’s werewolf in the WEREWOLF OF LONDON. Maybe it’s the prominent teeth and the low forehead.

Boris Karloff’s make up for the Abbot and Costello film A&C MEET DR. JEKYL AND MR. HYDE was sort of a cross between the March and Tracy look, though much cheaper.

The Classics Illustrated adaptation of the novel by Lou Cameron closely resembled the simian March version. Ironically Stevenson’s brief description of the character seems to resemble nothing so much as what we now know early homonids looked like, small, hirsute, and bipedal, but vaguely ‘other’ looking.

One reason the book was so popular at the time was because the Victorian’s were obsessed with atavism and prehistoric man — which was one reason scams like Piltdown worked.

I know the Broadway musical version with David Hasslehoff has been on television recently, but does anyone but me recall the musical version that showed on television with Kirk Douglas as Jekyl and Hyde.

And since Walter mentions it in passing the proper pronunciation is not the familiar Jeck-il, but Jee-kil to rhyme with ‘seek’ as in hide and seek, a little joke of Stevenson’s.

March 22nd, 2010 at 4:31 pm

Re: THE MAGICIAN.

Walter mentioned that it was going to be on, but as usual I parked the information away and promptly forget until about 30 minutes into the movie. I watched for a while, enjoyed what I saw, but not really knowing what was going on, I eventually turned it off, telling myself it was going to be on again, but mentally kicking myself where it hurts the most.

— Steve

March 22nd, 2010 at 5:31 pm

THE MAGICIAN was so interesting that I ordered the Somerset Maugham book because of the crazy plot and Alister Crowley connection. By the way Maugham’s long novelets are classic adventures along the white man’s grave type plot. He did many of these novelets for COSMOPOLITAN when it published excellent fiction in the 1930’s. Pulp fiction with a touch of Literature and first class characterization.

March 22nd, 2010 at 10:53 pm

Maugham is an old favorite of mine and much of his fiction has touches of pulp sensibility, at least in subject matter. He was particularly fond of the Englishman in the Far East or South Seas as a theme, and of course it isn’t just ‘The Letter’ or the ASHENDEN stories that touch on the matter. His ‘Lord Montdrago’ was a good segment of the anthology film THREE CASES OF MURDER.

NARROW CORNER about a man on the run who finds adventure, love, and redemption in the South Seas was filmed twice, once with Douglas Fairbanks Jr., and remade as ISLE OF FURY with Humphrey Bogart. Murder and crime also figure in the novel CHRISTMAS HOLLIDAY a good noirish little film by Robert Siodmak with Gene Kelly and Deanna Durbin.

As Walker says much of his work is ‘Pulp fiction with a touch of Literature and first class characterization.’

Maugham’s more literary short stories were the subject two excellent anthology films, QUARTET and TRIO. The Ashenden stories became Hitchcock’s SECRET AGENT and were later adapted for TV and shown here on A&E. More recently they were adapted for radio on BBC7.

March 22nd, 2010 at 11:38 pm

Actually there were three anthology films dealing with Maugham’s stories: QUARTET, TRIO, AND ENCORE. These films are available from amazon.com.uk at a heavy discount. You need a region free dvd player but all three are available as a set for about 7 pounds or $11.00. Maugham can be seen actually introducing the films. I’ve seen them all a couple times and also read the stories to compare with the adaptations.

March 23rd, 2010 at 12:25 am

Yes, I forgot about ENCORE. They’ve also been shown on TCM if you would prefer to record them yourself or don’t have a multi region or region free DVD player. At various times all of the versions of OF HUMAN BONDAGE have shown up on TCM, including the Leslie Howard/Bette Davis and Laurence Harvey/Kim Novak films as well as the harder to catch 1946 Paul Henried/Eleanor Parker version. THE LETTER shows up fairly regularly too as does THE PAINTED VEIL and it’s remake THE SEVENTH

SIN.

Also worth catching is either version of THE BEACHCOMBER based on Maugham’s story ‘The Vessel of Wrath’ about an unregenerate drunken Englishman on a South Seas island who is reformed by a missionary’s nurse sister during a cholera outbreak. Both the Charles Laughton/Elsa Lanchester and Robert Newton/Glynis Johns versions are delightful, the latter handsomely shot in color on location.

Anyone wanting to try out Maugham without spending anything will find a good many of his works available as free e-books.

Maugham was portrayed twice on screen by Herbert Marshall, in THE MOON AND SIXPENCE and THE RAZOR’S EDGE since Maugham often injected himself in the story as narrator.

ASHENDEN: OR THE BRITISH AGENT was based on Maugham’s exploits as a British spy during WW I. He served in intelligence again in WW II though not as effectively since by then his cover was well blown.

March 23rd, 2010 at 6:24 am

Well, we’ve morphed from Dr.Jekyll to Mr. Maugham. His THE MAGICIAN is rather well done, with fine horrific elements but also very real characters. Interesting that in the novel THE RAZOR’S EDGE he gives himself two very good scenes (well after all, he’s the author) but in the films those scenes were given to Tyrone Power and Bill Murray (well, they’re the stars.)

March 23rd, 2010 at 7:23 am

The video revolution is a great event in my life. Not too long ago, if I wanted to watch either version of THE BEACHCOMBER by Somerset Maugham, one of my favorite authors, I would have been out of luck, except for catching it by accident on TV.

Now, a quick check of my video tapes reveals I have the Charles Laughton version, a VHS tape, still in shrink wrap. I’ll watch it tonight after rereading the story. The other version starring Robert Newton is available for 48 cents plus $2.99 shipping on amazon.com. It’s now on the way to me with one click of the mouse.

We take all this for granted now, but it’s a great time of film buffs.

March 23rd, 2010 at 8:41 am

I’m somewhat surprised that my 25-year-old review has provoked so many comments, but it’s a well-deserved tribute to the artistry of Mamoulian, who is one of my favorite Hollywood directors.

I was delighted when I saw the listing for “The Magician” in the TCM program guide. Some viewers find the Ingram films, in spite of their great artistry, slow-moving. If not to the modern taste, they are very much to mine.

The fascinating tour of the MGM studios (circa 1925?) that followed the feature has been shown more than once on TCM but it was a welcome follow-up to the Ingram feature.

September 5th, 2010 at 12:40 pm

The first time I viewed this movie I was very terribly petrified being only 6 or 7 years old

now i Have my own copy and it Whenever i wish

March was great and forget Spencer Tracy

However I only watch in the evening

Emil derose excuse my typing