Sun 21 Mar 2010

Reviewed by David L. Vineyard: CARROLL JOHN DALY – Murder from the East.

Posted by Steve under Authors , Characters , Pulp Fiction , Reviews[7] Comments

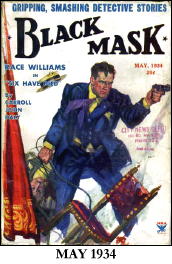

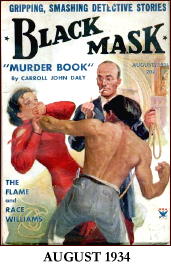

CARROLL JOHN DALY – Murder From the East. Frederick A. Stokes, hardcover, 1935. Previously serialized (as individual stories) in Black Mask, May-June, August 1934. Paperback reprint: International Polygonics, 1978.

Some books have everything — or nearly everything. Murder From the East is one of those. It has a bit of everything — the yellow peril, beautiful adventuresses, and tough guy private eyes.

And as the latter goes, there was never anyone tougher than Race Williams. And if you don’t believe it, just ask him.

His right hand, that was under his jacket, flashed into view. For the moment the hard square surface of a black automatic showed; jerked up so that I looked down the blue barrel of a German Luger.

Hard, red knuckles tightened and showed white. And — I shot him five times. Five times smack in the stomach, before he could ever squeeze the trigger.

Surprised? He was amazed.

So are we. But we shouldn’t be. Race Williams is the first private eye. True, Daly’s own Three Gun Terry Mack beat Race to the game, but Terry wasn’t a private eye, or a least never identified himself as one. He was an adventurer like Gordon Young’s tough gambler Don Everhard.

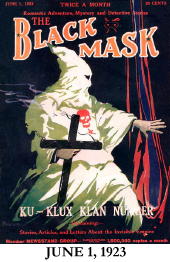

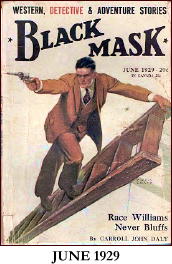

Race is the first of his breed (not the first private detective, but the first in the hard-boiled mode) making his debut in the Ku Klux Klan issue of The Black Mask in “Knights of the Open Palm.” Some of the stories were pro Klan — Daly’s was anti.

In Murder From the East Gregory Ford, who runs the biggest private detective agency in the city, is working for the government, and wants to hire Race to knock off a gunman who is gunning for Race anyway. But Race isn’t having any.

But before the day is over the gunman has run down Race and met his just end. Then the man who hired the gunman shows up in Race’s office.

His name is Count Jehdo, and he turns out to be from Astran, a country that is making trouble in Europe and Asia. He’s also involved in the “Torture Murders” the papers are screaming about.

Pretty soon Race is in the pay of the General, the man behind Gregory Ford, and the trail leads Mark Yarrow, the man behind the torture murders and Astran’s crimes but even he doesn’t know about the Number 7 man, the General’s man inside the organization, and Race’s job is to destroy Yarrow while the Number 7 man brings down Jehdo.

Then, who should show up but —

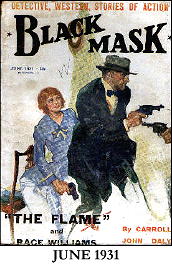

The Flame and Race have been at this game for a while. She’s up to her neck in this new game and wants Race out of her way.

But she has taken on more than a lover. She is now the Countess Jedho.

The rest of the book precedes in a hail of gun smoke as Race thins the numbers of the organization and generally makes a nuisance of himself. He’s captured and tortured, but escapes thanks to the Flame and eventually smashes Yarrow and Jehdo and reveals the Number 7 man.

Much has been written about Daly’s shortcomings as a writer, and most of it is true, but what is also true is that he wrote at a sort of white hot level straight from the hip, like the hot lead pouring from is blazing .45’s, and for all the melodrama, cliches and corn, there is a conviction to his best work that few writers ever managed.

In terms of style and literary considerations he is a pale shadow of Hammett and Chandler, and he could never plot or even created characters as well as Erle Stanley Gardner, but he was the most popular writer at the famed Black Mask, and his name on the cover drove sales up every month.

Time passed Daly and Race by. For a time his tales of Satan Hall, a Dirty Harry style cop, surpassed Race, and Race eventually fell from the Mask to lesser pulps as Daly’s career sagged. By his death in the 1950’s his books couldn’t find an American publisher.

For a time Race Williams and Carroll John Daly were kings of the hard-boiled private eyes. If they lacked the graces of the better writers they still offered their own brand of thrills and action, and in their wake marched the Dan Turner’s, Mike Hammer’s, and Shell Scott’s that followed. If nothing else Daly influenced Mickey Spillane, and in Spillane had a lasting impact on the genre.

Race and his creator are fairly insubstantial figures now, but once they were giants, and traces of their footprints still leave a trail. Park a few of your critical judgments and you can still find a good deal of enjoyment in Race’s adventures.

You may not applaud the writing, but you are likely to stay for the sheer entertainment. Perhaps more than many of the better writers from Black Mask, the true voice of the pulps thunders in the exploits of the one of a kind Race Williams.

March 21st, 2010 at 9:48 pm

A ‘hail of gunsmoke?’ I’ve been reading too much Daly obviously.

March 21st, 2010 at 11:57 pm

Collecting BLACK MASK I read alot of Daly’s work in the magazine. I always had a big problem with one habit that Daly used several times in the Race Williams stories and perhaps in the other series also. He would stop the story and have the hero talk directly to the reader. I guess many readers liked this gimmick but for me it always had the same result: the story stopped dead and I just found it unbelievable. After reading several novels and stories, I had to give up on Daly because he was just too crude, too hardboiled, too unbelievable.

Reading such writers like Chandler, Hammett, Paul Cain, Norbert Davis, Fred Nebel, Roger Torrey, and other BLACK MASK writers, made Daly’s fiction look rather silly.

March 22nd, 2010 at 12:24 am

Walker

No disagreement. Daly is full of undigested corn, melodrama, and cliche, but he is also a writer of some energy and his stories have a certain crude power that we associate with the pulps.

No one is suggesting he is in the same class as the best of the hard boiled writers (or even the middle rank), certainly not the best of the Black Mask Boys. Truth-fully, he can’t even compete with Robert Leslie Bellem for readability and invention, but I’ve always found his work compellingly readable for all of its crudities and weaknesses. Daly is the Model T of hard boiled fiction — it ain’t pretty, but it gets you where you are going.

And, as I said, his influence on one school of the hard boiled novel that reached its height with Spillane is undeniable, and I think, with a good deal of forgiveness, his best work is important for more than historical reasons.

Incidentally Spillane picked up that habit of stopping the action to talk to the reader usually justifying and stating Mike Hammer’s credo. Spillane did it much better than Daly, but it still originated with Daly and Race Williams.

The Satan Hall stories and books are a bit better written than the Race Williams stories, but even with his weaknesses Daly is worth reading for anyone who wants to understand the hard boiled novels origins, and with a bit of forgiveness shows us the bare bones of the genre in its infancy.

Daly has one film credit for the story to TICKET TO A CRIME (1934) for the screen story. I don’t know if it is based on a Race Williams story or not. Ralph Graves plays private eye Clay Holt, who unravels a case with secretary Peggy Cummings. Whether it is based on a Race Williams story or not it would be an interesting one to see.

March 22nd, 2010 at 5:17 am

I think we agree on Daly’s place in detective fiction. By the way Clay Holt, the private eye who appears in TICKET TO A CRIME, appeared in several stories in DIME DETECTIVE in the 1930’s and I remember him even in Street & Smith’s DETECTIVE STORY. So the story may be based on one of the Clay Holt stories, but knowing Hollywood I wouldn’t be surprised if they adapted a Race Williams story and changed the name of the hero to Clay Holt.

March 22nd, 2010 at 3:31 pm

Walker

Thanks for the Clay Holt info. Re Daly, I think our only disagreement is that I can still read him despite his flaws and enjoy them for what they are, but I don’t think there is much difference in our assessment of his talents such as they were.

March 22nd, 2010 at 5:39 pm

Since reading this I went back and reread “Three Gun Terry” and should revise this since he does identify himself as a private detective. I may have confused it with the narrator of “The False Burton Combs.” Still, I think Race takes the title if not precedence considering his success. Even Chandler experimented for a decade with Carmody, Dalmas, and Evans before coming up with Marlowe.

Private Detectives were fairly common before Daly. Arthur Morrison’s Martin Hewitt, Octavius Roy Cohen’s Jim Hanvey, and for that matter Nick Carter, Sexton Blake, and Secret Service Smith were all professional private detectives: And John Douglas in Conan Doyle’s THE VALLEY OF FEAR was himself a private detective (in fact some have suggested this was the first hard-boiled novel and is being reprinted as such by Hard Case). Nor was the hard-boiled voice entirely new, Gordon Young’s Don Everhard was as tough and gun proud as Race Williams ever thought to be. For that matter Eugene Vidoq, the first police detective had also been the first private detective when he was forced out of the police.

What Daly’s accomplishment is was to marry that hard-boiled tough voice with the urban private detective creating the character as we know it today. Race Williams comes complete with most of the important tropes of the character from the small office, the uneasy relationship with authority, the quasi legal standing, and the old west gunfighter comparisons. Whatever his weaknesses as a writer Williams is clearly one of the same company of private eyes from Sam Spade to Mike Hammer to Rockford and Spenser. Owen Wister’s Virginian wasn’t the first cowboy either, but the novel he appears in is likely the first western as we know the genre today.

March 22nd, 2010 at 5:54 pm

Thanks for going back and checking out that point about Race Williams and Three Gun Terry. I’d been meaning to do that myself, but as usual, hadn’t gotten around to it yet.

In terms of his being the first meaningful hard-boiled, urban-based PI, I think you make a good case for Race Williams as being the one.

— Steve