Sat 6 Oct 2012

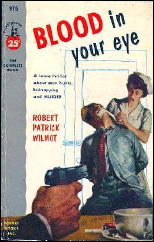

Archived Review: ROBERT PATRICK WILMOT – Blood in Your Eye.

Posted by Steve under Bibliographies, Lists & Checklists , Characters , Reviews[13] Comments

ROBERT PATRICK WILMOT – Blood in Your Eye. J. B. Lippincott, hardcover, 1952. Pocket 975; paperback, October 1953. Cover illustration by James Meese.

Blood in Your Eye is the first of three cases cracked by New York City private eye Steve Considine, and for the record, here’s a list of all three:

Blood in Your Eye. Lippincott, 1952; Pocket 975, Oct 1953.

Murder on Monday. Lippincott, 1953; Pocket 997, March 1954.

Death Rides a Painted Horse: Lippincott, 1954; Jonathan Press #80, abridged, no date.

You’re much more likely to like this one if you’re a fan of hard-boiled tough guy detective fiction; it really isn’t one that’s going to convert you. The cover of the paperback is (um) an eye-catcher, and the first 100 or so pages are terrific. By that time, though, while the pace hasn’t let up, the air has started to leak out of the tires, and by the time the book is over, you may have cause to wonder from where solution came, far left field?

To start at the beginning, though, Considine is hired to wet-nurse an actively practicing but generally amiable alcoholic on a plane trip to England, where a doctor is waiting for him. On the night before their departure, Charlie Gillespie, given in the past to hallucinatory and (hence) quite invalid misinterpretations of everyday events, claims to have seen a murder committed, and soon after, goes underground and disappears completely.

Considine’s job: find him, and thus we have a story. What I think I’ll do is give you two long quotes, both of which caught my attention in no uncertain terms, but in not exactly the same way. First, from pages 36-37, where Considine is alone in a bedroom with a girl who’s involved — and of course there is:

She bit hard and it hurt like hell and I went crazy mad, for a moment. I got my right hand into her hair and gripped it and spun her around and slapped her across the mouth with the flat of my bloody left hand. Then we were locked in tearing, panting embrace, me trying to hold her hands while she clawed at my face and jerked her knees up into my body, until I got both her arms pinned and pulled her so close that she couldn’t use her hands or knees, and I could feel her breasts swelling firm and big against my chest, and her curved long thighs against my thighs.

Desire and rage were so completely mingled within me that I twisted her wrist even as I kissed her lips — and I kissed her lips hard. Her head went back and she gave a long, sighing, panting breath, and for an instant her lips met mine wide and warm, and her body seemed to melt in a yielding movement that made it part of my own… Then she butted me solidly on the cheek with her head and twisted loose from my hands.

It’s quite a first date, even for a kindergarten teacher, which in fact she is, although Considine doesn’t know that yet. He continues:

The girl’s name is Carla Paul, and later on — here’s the other quote coming up now — Considine is talking the case over with the cop on the case. From pages 65-66:

“Sometimes,” I said, wondering what-the-hell.

“You know how it is in those stories,” Christie said. “They got a regular formula. The hero is always a bright gum-shoe, with ideas, and he’s always getting fouled up with a lot of stupid, sadistic city cops who do everything they can to prevent him from solving the crime.”

“I bet you could write yourself,” I said. “How do you know, if you haven’t ever tried?”

Christie ignored my remark. “So, because of the dumb cops, our Shamus hero has to more or less take the law into his own hands. In order to bring the villain to book, it’s necessary for our hero to break every law in the book, himself.”

“Tell me more,” I said.

“Take a case like this,” Christie went on. “The cops might wanna case Carla Paul’s room, just to see what they could see. But they’d need a warrant, because if Carla or the landlady came in while they were shaking down the place, there’d be hell to pay. If it did happen to be a case of mixed identity, I’d hate to be the cop who happened to be caught with a handful of her unmentionables.”

“Time presses,” I said, “so suppose I just take the story from here. The Shamus in your story isn’t inhibited by legal red tape or bothered by stupid principles against the search. Right?”

“Oh, so right,” Christie cooed.

“So he waits until Paul isn’t home,” I said, “and he opens her door with a skeleton key, or maybe a strip of celluloid because that makes it sound harder. He goes into the room and combs it good, and maybe he finds something — a letter or something — that gives him a line on Mr. Blair? Okay so far?”

“Perfect,” Christie answered, avoiding my eyes. “I doubt if Raymond Chandler himself could do better.”

“There’s only one thing wrong,” I said, “and that’s the possibility that someone may come in and catch the bold hero in shaking down the apartment. Someone like a big, tough policeman, for instance. Or a two hundred and fifty pound wrestler, who doubles as a janitor.”

“That ain’t in the script,” Christie said, “but I’ll admit it would be awkward if it happened.”

“Yes, wouldn’t it? And then our Shamus gets carted off to the nearest police station and placed in a backroom where a lot of uncouth persons ask impertinent questions about him having been in the apartment. And then maybe Shamus gets so indignant that he gives a discourteous answer, and loses some of his teeth.”

I flipped my cigarette at the cuspidor and grinned at Christie. “I need my teeth, lieutenant. I might be sent out on a job that paid so well I could afford to eat steak.”

Christie rolled a pencil around on the desk top and looked at me thoughtfully. “Of course,” he said, “the Shamus could always ask to speak to Lieutenant Christie.”

“No doubt he could,” I said, “and by the time he got to talk to Christie, our hero would have a pocket full of teeth. See you later, Chris.”

We went out, and as we closed the door, Christie sighed again.

I don’t know about you, but for me, that was worth the price of admission, right there. I also have to admit that there was a time, about half way through, that I had absolutely no idea where the story was going next, and that’s doesn’t happen, or at least not very often.

You may take that as a good thing — I do — but what it also means it that it takes a full final chapter that’s ten pages long, after the bad guys have been named and identified, to tie up all of the loose ends, or at least all but one, a huge, massive coincidence that Wilmot dares not even mention, but I will. Possible? Sure, but without it, it all falls apart.

[UPDATE] 10-06-12. I’ve not been able to find any personal information about the author online, but I did come across a reference to one quote that’s interesting. From the cover or jacket flap of a British edition of Death Rides a Paper Horse: “Robert Patrick Wilmot has been compared by Anthony Boucher of the New York Times to the young Dashiell Hammett.” I have not found the quote from the Times itself, but it does suggest that reading the book again may be in order, or even all three of them.

October 6th, 2012 at 6:58 pm

Robert Patrick Wilmot started off with quite a bang in MANHUNT DETECTIVE STORY MONTHLY, March 1953, which was the third issue of this excellent crime fiction digest. On the back cover is a pen and ink drawing of Wilmot smoking a cigarette and the blurb says:

“Robert Patrick Wilmot, whose Triple Cross marks his first appearance in MANHUNT, caused a sensation with his first novel, BLOOD IN YOUR EYE. The New York Times labelled him one of the best mystery writers to come along since Raymond Chandler.”

The April 1953 issue of MANHUNT has his second story, The G-Notes, which is 19 pages long and the best story in the issue. My note for the story says “Very effective tough and hardboiled story-maybe too tough.”

The inside back cover has the department “Mugged and Printed” and gives the following information about Wilmot:

“…was born in Butte, Montana and ran at sixteen to Mexico. He took a fling at Hollywood and did stints in Minneapolis and Chicago as a reporter. For some years he was the reluctant proprietor of a traveling carnival which he inherited from his father. When the depression and hostile sheriffs put the carnival out of business, he became a publicity man and eventually editor of a large newspaper in the Pacific Northwest.”

Then in the May 1953 issue the blurb tells us that:

“…he’s seen every skid row from Borneo and back-and that he’s come across every type of character in most of them. This and his skilled writing accounts for the realism in his yarns.”

October 6th, 2012 at 9:13 pm

Thanks, Walker. That’s all extremely interesting.

I meant to check to see what Al Hubin said about Wilmot, but I forgot.

There’s very little. No year of birth nor death, only “Born in Montana; reporter and newspaper editor, radio and song lyric writer; living in New York City in 1950s.”

In spite of his work being compared to either Chandler or Hammett, Wilmot’s career in writing crime fiction seems to have limited to only three years, 1952-1954, only to have disappeared again, as suddenly as he appeared.

October 7th, 2012 at 1:52 am

I am sure I have in my paperback collection “Blood in Your Eye”, perhaps also “Murder on Monday”. All three novels were published as hardbacks by the British publisher Boardman in the “American Bloodhound” series.

October 7th, 2012 at 9:13 am

An article in the NY Times of April 24, 1941,

p. 15 mentions Robert Patrick Wilmot as editor of the Portland (OR) labor paper THE WOODWORKER

an organ of the Columbus River district of the CIO’s International Woodworkers of America

giving testimony that he had seen Harry Bridges

at Communist Party meetings in Portland and

that the CIO leader once told him “We Communists must stick together”

I would imagine the CIA would have a file on him somewhere in its papers on the Communist Party.

Anyone who might want to track down Mr. Wilmot’s whereabouts in 1954 could send away

to the Copyright Office for the details of

where Wilmot was living when the book Death

Rides A Painted Horse came out The registration number of the book was A124651

October 7th, 2012 at 10:01 am

Great work, Victor. It’s good to know that there was a Robert Patrick Wilmot before his crime fiction days, and that some of the background information on him was actually correct.

August West has a rave review of “Stakeout,” one of Wilmot’s stories in MANHUNT (the May 1953 issue) on his blog. He says in conclusion:

“All tightly packaged up in a handful of pages, that spins and catches the reader off guard. Exceptionally good, with characters that interlocked together dangerously. Robert Patrick Wilmot sure was an author who had talent!”

http://vinpulp.blogspot.com/2008/11/stakeout-by-robert-patrick-wilmot.html

October 7th, 2012 at 10:02 am

PS

If not the CIA, then the FBI. I should also mention that to get to an author’s whereabouts when his or her book was registered, the Copyright Office charges $8.50 provided one can supply the registration number, otherwise it is

some ridiculous price.

Victor Berch

October 7th, 2012 at 10:12 am

Josef

I’ve sometimes wondered about the the connection might have been between TV Boardman, publisher of the “American Bloodhound” series in hardcover, and MANHUNT magazine in the US, where Wilmot’s short stories first appeared, about four or five of them.

From http://www.dandare.info/biblio/boardman.htm

“In May 1961 Boardman started to reprint the original US detective magazine Manhunt under the title Bloodhound Detective Story Magazine and it ran for 14 issues.”

October 7th, 2012 at 11:27 am

I have 5 of the BLOODHOUND DETECTIVE STORY MAGAZINES and probably Boardman just realized what a great magazine MANHUNT was and got the rights to reprint the stories. The covers and stories look just like the MANHUNTS but the inside illustrations are different.

October 7th, 2012 at 11:38 am

I think that’s the reason why I never collected any of the Bloodhound magazines, that it reprinted only stories from Manhunt. Or should that be “mostly,” not “only”?

October 7th, 2012 at 3:53 pm

I looked again at my 5 issues of BLOODHOUND and all the stories looked like they were reprinted from early issues of MANHUNT. I also checked one of my favorite reference books, Michael L. Cook’s MYSTERY, DETECTIVE, AND ESPIONAGE MAGAZINES. This book should be in every mystery magazine collector’s library.

Robert Adey in his piece on BLOODHOUND, says the stories “…were unashamedly MANHUNT.” From the 4th issue on there was a statement that “This magazine is a British edition of MANHUNT.”

So I would say it looks like BLOODHOUND rerpinted “only” stories from MANHUNT.

October 8th, 2012 at 6:51 pm

This was a very interesting article, about an author completely new to me.

You can really learn a lot here!

March 8th, 2014 at 7:12 am

Hi, I happened on your site after Googling for images of my father’s books…my daugter is interested in reading some of them.

Thanks for the interesting posting & information; I had forgotton about some of the things mentioned….like the carnival; reportedly aquired by my grandfather in a card game.

What’s the interest in where he was living in 1954?

March 8th, 2014 at 1:04 pm

Hi John

Thanks for stopping by. I’m happy to know you found this post and the followup comments both interesting and useful.

I think the significance of the year 1954 is that is when your father’s last detective novel came out, and we were wondering why he stopped writing — mystery fiction, at least.