Sat 5 May 2007

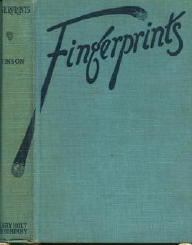

Review: HUNTER STINSON – Fingerprints.

Posted by Steve under Authors , Pulp Fiction , Reviews[3] Comments

HUNTER STINSON – Fingerprints

Henry Holt & Co.; First Edition, March 1925.

After a short investigation on my part, I believe that I can safely say that this is the only edition that was published of this book, nor were there any other books that appear under this author’s name. (The asking price for the only copy found on the Internet at the time I am writing this is $50, but that is certainly explainable by the fact that that particular copy is inscribed by the author; otherwise it is in about the same condition as mine.) FOOTNOTE.

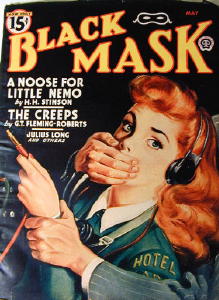

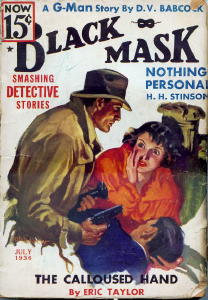

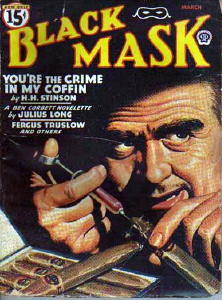

Long time readers of the pulp magazines may, however, suspect that they know the author by a slightly different name, and they would be correct, if they happen to be thinking of H. H. Stinson. An incomplete list of his short fiction at Bill Contento’s Fiction Mag website begins with a western story published in Top Notch in 1928 and ends with a mystery yarn in Black Mask in 1948. In the latter magazine he had a series character by the name of Kenny O’Hara.

To discover more, I put out a call for help, first from Victor Berch, whose name has been mentioned on these pages before, then from the various members of the Pulp Mags yahoo list:

[From John Locke:] He’s mentioned in The Black Mask Boys [edited by William F. Nolan]:

H.H. Stinson’s series hero was quick-fisted Ken O’Hara, of the Los Angeles Tribune. Again, a very tough cookie.

From the AFG Bulletin, July 1, 1936:

Your request to select a “model” story in the July Black Mask, or in almost any issue, for that matter, cannot be fairly done without a word of explanation. You see, we follow the principle of “no dud in any issue;” therefore it is rarely that any one story stands out markedly from any other or all of the balance, although we hope that the magazine itself, as a whole, does.

So far as the writers permit, we select for an issue the best of as many types as are available; in consequence, readers naturally have preference for one over another in accordance with their individual tastes, and all may be equally good as to workmanship quality. There is a story in the July issue, however, which can be pointed to for a specific reason. It is “Nothing Personal,” by H. H. Stinson.

If a new writer should ask me to suggest what might be interesting to our readers, I would probably mention anything but what Mr. Stinson has in his story, in the way of characters, by name or position – that is, a reporter, an editor, a tough police official, and so on. They have been used so many, many times.

Yet Mr. Stinson has done something with these familiar identities, with the ordinary action, which, to many readers, will make this an outstanding, a “model” story, in any company. The one word to describe it is “treatment.” He has brought every one of his characters vitally alive. The fact that they are this, that or the other is less important than that they are “real” personages; not once do they speak, act or react out of character – with a more or less commonplace setup, his handling of story detail, of constant menace, of action, is masterly. One careful reader refers to one of his scenes as the most vivid, the best of its type since Hammett told about Ned Beaumont in The Glass Key.

The fact that Mr. Stinson is himself a newspaper man, a police reporter on one of the big Los Angeles papers, may have contributed to the sense of reality which he has infused into the story. But it isn’t every newspaperman who can make a story live and throb like this one. If it were, editors would have an easier time.

A “model” story. No – except for treatment. A marvelously entertaining and vital one? Yes – decidedly yes.

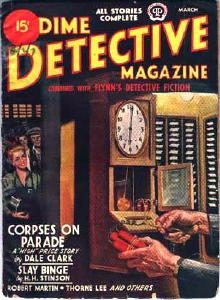

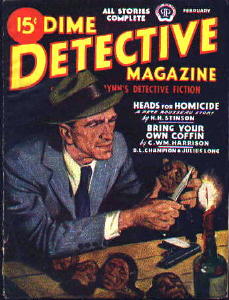

[From Ed Hulse:] Besides O’Hara in Black Mask, Stinson in the post-WWII years wrote a series about a dick named Pete Rousseau for Dime Detective.

He stopped writing for both Mask and Detective in 1948. He wrote for other detective pulps, too; Cook-Miller credits him with 60-odd stories altogether.

[From Will Murray:] I just went through my copy of the manuscript of the Joe Shaw bio written by his son, Milton. I find no mention of HHS.

However, Shaw did pick one Stinson story for possible inclusion in his Hard-Boiled Omnibus, “Give a Man Rope.” His editor thought it weak in comparison to other selections and it was dropped along with several others.

So we know what Shaw thought was his best BM story.

Me again. I’m back, and I’m assuming that after all of this talking, as interesting as I hope you found it, you’d like to hear about the book itself. Truth be told, it’s not very good, but for most of an evening or two, the entertainment value is still high enough that I did. Read it in an evening or two, that is.

As the story begins, the primary protagonist has discovered that as of that very same morning, he is a pauper. The estate he believed that had been left to him by his overly generous father, he learned, had been badly (and sadly) overtaken by various notes, mortgages, liens and debts. Which therefore means, as of that very same evening, his marriage to Maryse Douglas is off.

Not by any wishes of the young lady herself, far from it, but by Owen Kenrick, her guardian until she comes of age. Here is how the author describes the young lady, on page 5:

The next morning Christopher is consoled by a gent by the name of Bosworth, who lives in the apartment upstairs from him. From page 13:

This is not the sort of dialogue that would make any kind of headway in the pages of either Black Mask or Dime Detective, nor would the mystery itself. When Kenrick is found dead, young Christopher is, of course, the obvious suspect. The only others in the running are the butler or Miss Douglas herself, and when Christopher’s fingerprints are found on the murder weapon, that just about clinches the case right then and here.

Except for one undeniable fact, and that is that Christopher did not do it, and in the remaining 200 pages, it is up to him, Maryse, and Bosworth (who has secrets of his own) to prove it.

Also on Blake’s trail are a gang of jewel thieves (jewelry being a primary item of trade for the dead man) who kidnap Maryse as part of their nefarious doings, but she escapes and makes her way back to the city just as Blake and Bosworth discover the hideout where she had been kept a captive, and mystery upon mystery ensues. By page 209 Maryse has been captured again, by yet a third party to the drama, and rest of the book is devoted to her rescue, nothing more, and quite a lot less.

A lot happens in this book, as you can tell, but when it comes down to it, as I’ve already implied, nothing really happens, if you know what I mean. And what about the phony fingerprints? You might ask, and rightly so. In 1925, they were still a novelty to mystery readers, and so in 1925 they must have been amazed as to what could be done with them, by both the investigators and (in this case) the villains. I checked online with Google, and guess what, what the chaps on the wrong side of the law did back then could really be done. Of course Mr. Stinson makes it sound easy, but in terms of the technology of 1925, I’m still not quite convinced it would have been as easy as he made it sound.

FOOTNOTE: I seem to have spoken somewhat ahead of myself. After some further investigation I have discovered that the novel was previously published as a three-part serial in the mystery fiction magazine Real Detective Tales and Mystery Stories, concluding in the February 1925 issue. Mostly, I think but am not sure, the stories that appeared in RDT&MS were either of the mansion house variety or out-and-out thrillers, and thusly not hard-boiled fare at all.

Or am I making a judgment on a sample of size only one? Other authors who appeared in the magazine in 1925 include Seabury Quinn, Arthur J. Burks, Raoul Whitfield, Otis Adelbert Kline and Vincent Starrett. You tell me.

May 6th, 2007 at 12:59 pm

Thanks for the info, very interesting! Stinson’s photo can be seen at least in Frank MacShane’s biography of Chandler, you might want to scan it. It’s in the photo of Fictioneers (or whatever the pulp writer gang was called).

I’ve read some of Stinson’s stories and remember they were pretty good. One of the stories had Kerry Monahan as the hero. Don’t know the original title for it, neither do I know if Monahan was a series character.

Stinson wasn’t the only hardboiled writer to have written cozies before turning into hardboiled. Frederick Davis also wrote some pretty annoying cozy stuff in the twenties and there must’ve been others.

July 14th, 2010 at 10:25 pm

Mr. Stinson was married to my cousin, Evelyn Nichols Stinson. She was an actress and played “Rosemary” in her sister’s play “Abie’s Irish Rose” on Broadway in the 1920s. Mr. Stinson did write some plays. He and his wife had a son and a daughter.

March 21st, 2013 at 2:26 am

Found original manuscripts by HHStinson. Would like to know list of what was published. Also very old letters by Leonard family, related to HH.