Tue 22 Jun 2010

A Review by Curt Evans: JOHN DICKSON CARR – The Problem of the Green Capsule.

Posted by Steve under Reviews[22] Comments

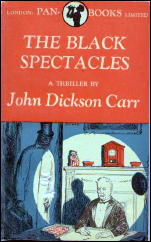

JOHN DICKSON CARR – The Problem of the Green Capsule. Harper & Brothers, US, hardcover, 1939. Published in the UK as The Black Spectacles, Hamish Hamilton, hardcover, 1939. Reprinted many times, in both hardcover and paperback, including: Books, Inc., hc, 1944; Pan, UK, pb, 1947; Bantam #101, pb, 1947; Berkley, pb, 1970; Award, pb, 1976; IPL, pb, 1986.

A series of poisonings of village children by means of doctored chocolates brings in a Scotland Yard detective, Andrew Elliot. While he’s there, it is learned that another murder has taken place: that of Marcus Chesney, a local millionaire whose niece, Marjorie, has been suspected of the earlier poisonings.

Chesney has died from poisoning! And he was being filmed at the time he was poisoned! Chesney was doing a demonstration of how the doctored chocolates had been substituted for the innocent chocolates in the village shop, testing the perceptions of an audience of three people: Marjorie; Marjorie’s fiance, George Harding; and a neighboring friend, Professor Ingram.

Chesney’s brother, Doctor Joe Chesney, had had to absent himself from the performance, while Marcus’ employee, Wilbur Emmet, was a participant in the performance, as the mysterious, muffled Mr. Nemo.

It is “Mr. Nemo” who forced a presumably poisoned capsule down Marcus Chesney’s throat. But Wilbur is found concussed in the yard after the performance. Was Wilbur really Mr. Nemo, or was someone else masquerading as him?

All three members of the audience seemingly have perfect alibis — they were watching the performance. Dr. Joe was attending a patient. So we have an impossible crime once again, though more in the nature of an alibi problem: how was someone able to get in position to poison Marcus?

I find this on re-reading still to be a very good detective novel, with an interesting problem, lucidly elucidated at the end. Some may find it short on action, but that’s okay with someone like me, who finds some Carr’s too active.

Interestingly, the Carr stand-in hero here is a young police inspector. On the whole, this works well. Dr. Fell does not appear until halfway through the book, and a very good police investigation is conducted until then. Then Inspector Elliott meets Dr. Fell, shouts that he loves Marjorie and confesses that he has concealed that he knew before taking the case that Marjorie tried to buy poison.

Fell (who it turns out is suppressing evidence about Marjorie as well) compliments Elliott on his chivalry. This put me off a bit. It seemed Carr’s romanticism getting the better of good sense. Any policeman behaving that way should have been drummed out of the force.

And that Elliot could have been “in love” with Marjorie to that extent after seeing her once in Pompeii (Pompeii is for lovers?) seemed absurd to me. But I think I’m the first person ever to complain about this, so I guess it isn’t an issue with most people.

The characters are solid enough, classic Carr stock. We have the disputatious academic (Professor Ingram); the bluff, hearty fellow who roars a lot (Doctor Joe); the goody two shoes, obsequious male (George Harding — though did Carr really need to give us as black marks that he has “Southern European” looks and went to a “minor” public school, oh dear!); and the beautiful girl who is either an angel or a devil.

The police are nicely characterized (Major Crow only sounds like Carr once, when he informs Elliott of Marjorie: “For all her sweetly innocent looks, I hear she sometimes uses language that would startle a sergeant-major”).

There’s a lot of roaring from the male characters that goes on in this book (Dr. Fell even makes a roaring whisper, I don’t know how). I could do without the roaring myself, and I know this got on Barzun’s nerves.

After reading Doug Greene’s excellent biography of Carr with all the information about his drinking, I can’t help wondering if the drinking bouts kind of influenced Carr’s writing in this regard. After all, drunken people do often roar and shout. Or maybe Carr was just naturally excitable.

We know he was strongly attracted to the more romantic past. It’s interesting that he was such good friends with the phlegmatic John Street. Of course, both Carr and Street had a fascination with and great talent for murder mechanics.

Carr often coupled this talent for murder with a Christie-level skill at misdirection, which makes him a truly major figure of the period even if one does like all his stylistic quirks. Barzun and Taylor are far too harshly critical of Carr (and it should be noted they never read many of his best books).

Nitpicking aside, this seems to me one of Carr’s strongest books. Not flashy, but a fascinating problem. One part of the explanation has a beautiful simplicity, but chances are the reader will miss it until it is revealed!

Editorial Comment: Curt has recently been re-reading a number of books by John Dickson Carr. This is the fourth in a series of reviews he wrote as a result. The Corpse in the Waxworks was the third, and you can read it here.

June 22nd, 2010 at 9:18 pm

I suppose when you model your sleuths on G.K. Chesterton and Winston Churchill some roaring is to be expected.

As for Elliot — love at first sight does happen — and even seems likely to one of Carr’s romantics. I suppose if we took Elliot seriously as a Scotland Yard man at all his behavior would be reprehensible, but as a Carr hero it’s just what you expect.

This is not a favorite, but overall a good entry even with the roaring. And as for the ‘roaring whisper’ I suspect that was taken directly from Chesterton — in fact I think I have read the term in some reference to him — it also sounds a bit like something Professor Challenger would do. It is not the misnomer it sounds to be — I’ve known a few people who whispered in a roar.

And drinking in general gets a good deal of attention in the Golden Age, though it never seems to have the same effect in fiction as in reality. At least the heroes of the hardboiled school have the good grace to sport the occasional hangover.

Still for all that, and all the quirks that Barzun and Taylor so complain of, Carr remains remarkably readable, and there is nothing dry or bloodless about his work. The roaring, swashbuckling, and bouts of romanticism do get a little overbearing at times, but I can’t say it much bothers me. I’m usually having too much fun to care.

June 22nd, 2010 at 9:48 pm

I simply don’t enjoy Fell much as a character, though, oddly, I do like H. M. a lot. Fell just seems a collection of artificial mannerisms to me. H. M. is highly exaggerated, yet somehow I find him believable.

How one feels about the stylistic quirks depends on one’s feelings about “realism” in a detective novel. I tilt more to realism than most Carr fans, I suppose (and certainly Carr himself). I just couldn’t believe in the whole “I’m in love at first sight, so now I’ll behave completely unprofessionally” aspect of the plot; and that did interfere with my enjoyment of the book.

I felt like the hero was an absolute bonehead. Is it really the “thing to do” for a policeman to conceal incriminating evidence in a murder investigation because he has fallen in love at first sight with the woman implicated? I suppose you could make a good moral dilemma novel out of this, but Carr just passes it off simply as natural chivalric behavior. And Fell abets it! Bah. But I’m sure Carr would say I’m a bluenosed Puritan with water in my veins.

On the other hand, I thought a great deal of it was very clever and I would rate it highly overall. The Carrisms don’t get really bad until the 1950s and 1960s, when, to be honest, a lot of his work becomes nearly unreadable for me. The characters behave like children (mudfights in Night at the Mocking Widow, etc.). I like at least an appearance of surface realism, unless you just go completely for broke with baroque fantasia, like the Bencolins or some of the books by Michael Innes or Gladys Mitchell.

So I guess I’m somewhat in agreement with Barzun on the style aspect, though I think he is much too dismissive of Carr, who I really do believe, with most aficionados I’m sure, is one of the greats. His locked rooms are brilliant, his clueing often nearly as adroit as Christie’s and his writing atmospheric.

One plotting complaint, however. I’ve found, as here, you can often guess the Carr murderer based on a knowledge of his personal likes and dislikes. Christie was more self-effacing in that respect, which is one reason I still put her at the top.

June 22nd, 2010 at 9:50 pm

I didn’t care much for this book, it seemed very slow. The solution, though, was very neatly done indeed.

June 22nd, 2010 at 10:08 pm

Well, I’m partial to the Humdrums, so I think the slowness worked for me. For much of the book, indeed, it’s almost like a classical Humdrum police investigation (albeit with Carr’s Chestertonian knack for quirky events). I didn’t need for there to be an emotional element, because I loved the problem.

On the “roaring whisper” bit, lol, I thought a whisper meant to speak softly? I know people can shout SSSHHHH!!!!!! but that’s not really a whisper, darn it! Okay, I’m nitpicking here, but I guess I just do not like that Dr. Fell. Why it is I cannot tell. But this I know and know it well, I do not like that Dr. Fell. 😉

You recall when I said I would have liked He Who Whispers better without Fell (though he is recessive there), perhaps. Yet I love H. M. He’s probably my favorite comic detective and one of my favorites overall. That’s probably why I tend to rate the Dicksons higher than the Carrs.

June 22nd, 2010 at 10:41 pm

Curt

Re-Fell, he is very close to the real Chesterton who was larger than life and twice as blustery — I’m sure if he ever got the chance Chesterton would have been just as outrageous and high handed as Fell — he certainly drank as much, dressed the same, and in general was thoroughly theatrical.

Frankly Ellot doesn’t bother me here because few of the Golden Age greats have the faintest grasp of actual police work. New Scotland Yard is the administrative headquarters of the London Metropolitan Police Force, and while they did travel outside of London for investigations and to assist in investigations at the request of the local police they wouldn’t have been involved in half the crimes they investigate in the course of the Golden Age. They are not, and never have been, a national police force summoned whenever some local bigwig dies at a great home. Allingham gets the details right in some of her later books with Luke working out of a specific station, but most of the GA writers made little or no effort at that sort of realism.

As for the realism I confess in Carr’s case that is the least of my concerns. I’m not really sure what you mean by realism in relation to these books in general. Appleby doesn’t even bother to look at the body half the time. Frankly Edgar Wallace’s police procedure is better than fully half of the Golden Age greats. They knew they were writing in an artificial construct and assumed we did too and offered that to us as a game.

So long as the writers don’t violate the space time continuum, the laws of physics, or go too far out on a limb I give them a good deal of leeway. Carr isn’t trying for realism, and I would argue didn’t give a fig whether he was realistic or not so I give him his game so long as he entertains me, and if he needs a romantic Scotland Yard man to protect the girl he loves I’ll let him have his way.

Of course, if it bothers you, it bothers you, but looking overall at the genre I’m not sure I can find much I consider realistic outside of Freeman and Thorndyke or perhaps Inspector French or Henry Wade’s Poole. If there is a single realistic moment in all of Sayers I missed it — her rural settings make COLD COMFORT FARM look normal — you have expect the locals to tug their forelock whenever Wimsey deigns to speak to one of them.

As for the predictability of the killer at least unlike Van Dine the killer doesn’t always show up on the same page and unlike Christie the young lovers aren’t usually the murderers. I grant Carr’s personal prejudices show up in the killer, but so do Sayers and Christies.

I agree with all your critiques of the book, but would say rather than failing as realism the characterization of Elliot fails because it is a rather obvious ploy to get around a difficult situation and create a bond between Fell and the Yard man.

And from personal experience I can tell you love at first sight can be powerful enough for even a policeman to violate the rules. That bit is far more realistic than it may seem.

June 22nd, 2010 at 10:44 pm

Curt

Re “Roaring Whisper” it is known as a “Stage Whisper” one that can be heard in the back of the theater. I’ve known many a deaf person guilty of it and a few who hear perfectly well. I give Carr this one largely because I’ve known a number of people incapable of being quiet even while whispering.

June 23rd, 2010 at 12:28 am

David, to be honest, I’m not sure I would have “believed” Chesterton as a character either–and I think a little of him would have gone a long way (though I like Father Brown a great deal)! By the way, Carr didn’t actually meet Chesterton, or did he? I seem to recall in Doug Greene’s bio reading that Carr was disappointed not to have met him.

Fell just doesn’t do much for me. He’s a collection of rumblings and cryptic utterances. People can say the same thing about Poirot, say, but I believe in Poirot, that he really has a life somewhere in the Golden Age beyond. I enjoy his banter with Hastings and Hastings substitutes.

On the “realism” question, all I can say is Elliot’s behavior for me grated. As I said in the piece, I seem to be the only person who has made this complaint, but there it is! It’s not so much a demand for police procedural realism on my part, but simply human realism, or what I see that as being. Sayers’ police procedure may not be realistic, but at least Harriet Vane’s emotions as a lover, say, are, or they seem so to me.

Carr’s characters sometimes seem more like they came out of the seventeenth century (a time Carr loved). It’s no surprise to me that he turned more to historicals as he lost zest for modern life. But then you ended up in the present-day Fells with things like the duel in The Dead Man’s Knock that seem even more out of place.

Carr’s British publisher once criticized The Arabian Nights Murder and the fantastic strain in his work, saying that sort of thing was too much out of the reader’s experience and suggesting that Carr write something more realistic and everyday. So he ended up with The Burning Court, a story about witchcraft! But, the funny thing is, the everyday setting and its juxtaposition with the fantastic works splendidly. I think it’s one of the best books he did. If that sort of thing ever COULD have happened that’s exactly how it WOULD have happened! I believe it all when I read it.

June 23rd, 2010 at 1:05 am

Personally, I’ve always preferred the more bizarre and fantastic of his books. It’s a bit like a taste for really spicy foods. You either like this sort of thing or you don’t, and there’s nothing wrong with personal taste. Since my wife became interested in True Crime literature, and has shown some of the dafter cases to me, I have begun to feel that if people behaved in literature as they behaved in real-life, then no-one would believe it. Similarly, the ridiculous coincidences that occur regularly in the real world would simply not be allowed in a book!

June 23rd, 2010 at 2:02 am

Bradstreet

I’ve been following this discussion between Curt and David, and I’ve been thinking exactly the same thing. The coincidences that happen in real life, no author would dare put in a book.

No good author, that is.

I’m also thinking sports fiction. It used to be popular, back in the 1940s and before. Now it’s dead and it’s not coming back. Who could write a baseball story in which a perfect game is ruined with two outs in the ninth by an umpire’s blown call, or a soccer game in which …

You know what I mean?

— Steve

June 23rd, 2010 at 2:22 am

I’m certainly not advocating my view is superior. I believe all these things are matters of taste. And among GA fans, more are going to agree with the Carr position, I have no doubt. I’d have Barzun on my side, but he’ll be 103 this year, don’t know how much longer I can count on him.

Let me add again, though, that I think Barzun and Taylor are much, much too negative about Carr. He obviously was a great figure in the genre. I’m not even an advocate of absolute realism in the detective novel; I think that would be absurd. But I need to be able to believe it on the surface, if you know what I mean. In this book I would have had an easier time with it had the hero not been a police detective. I was lulled into the opening when he acted like a police detective, then he became the usual impetuous Carr hero (often something of a bonehead!).

I like Carr better too when he doesn’t stir the emotional pot so much. One of my least favorite Carrs is The Problem of the Wire Cage, where he makes everything so Tense! Tense! Tense! I guess I do think detection should tend to be a bit calmer than that. There seems to me a reason for segregating thriller/suspense elements from detection proper.

Another of my favorite Carrs is The Judas Window, where the courtroom stuff is brilliantly done and H. M. is funny. In later Dicksons H. M. gets out of control (one might suspect he is losing his mind), but in the earlier books he is splendidly funny and keen as mustard.

June 23rd, 2010 at 5:05 am

Curt

It is all a matter of personal taste, and ironically most critics complain about H.M. for exactly the reasons you don’t care for Fell, plus H.M.’s tendency to slapstick comedy. I like them both, though I will grant it took me longer to warm to Fell. I prefer H.M. too, but I think Fell was much closer to Carr’s heart — toward the end I think he had trouble sustaining H.M. as a character which was never true of Fell. And in the long run I think many of his best books are in the Fell series.

I know what you mean about emotional realism, but I always think of Christie’s masterpiece MURDER ON THE ORIENT EXPRESS, which is a wonderful book and a classic of the GA form — but the plot so absurd and contrived as to border on fantasy psychologically and practically. But Christie brings it off and I never find myself thinking about how unlikely it is until well after I have finished. Obviously Carr failed in that aspect in this one for you, I’ve only been pointing out why it didn’t bother me as much as it did you. I wasn’t bothered by Elliot’s actions because I didn’t believe him as a policeman in the first place.

And where would the genre be without numbskull heroes? Sad to say even a few of the genre masterpieces would fall apart like a house of cards if anyone used any common sense.

And granted Carr cared even less than most for the probability of his plots and characters. Even Anthony Boucher took him to task for playing fast and loose with the English language in one book in order to throw the reader. As you say most of his characters would be perfectly happy in a 17th century setting.

I’m not sure that Carr knew Chesterton, but he was a well known public figure and easy to draw on and caricature. His famous debates with George Bernard Shaw and his other public appearances and public persona meant that he didn’t really need to know him in order to model Fell on him. I was only pointing out that the theatrical Dr. had a real life model and if anything Carr toned him down a bit — hard as that is to believe. By all accounts Chesterton was drunker, louder, and more theatrical than Carr ever dared portray Fell.

I’m not sure I agree about Harriet Vane and Wimsey. I do appreciate Harriet is a much more realistic character than the usual romantic interest we have come to expect, and the romance is probably more realistic than most in GA fiction, but I’m afraid it always felt a little contrived to me — the only way Sayers could really get Lord Peter. I love Sayers and her books overall, but there is a nasty mean streak in her at times, and with the exception of Chesterton she is the writer I most often have to forgive for her racism — and her snobbery.

And I grant I enjoy the tension and thriller elements in Carr. I can enjoy a good humdrum too, but sometimes you want a bit of pot boiling thrown in. There are some books in the genre that are so bloodless in their pursuit of the pure puzzle you wonder the murderer worked up enough passion to commit a crime in the first place.

I love THE JUDAS WINDOW, especially when H.M. insults the jury as he addresses them, I’d love to see Perry Mason try that.

Even at 103 having Barzun on your side is pretty good support.

Steve

Truth is not only stranger than fiction it is often more contrived and trite than fiction too.

Praised for his realism, most of John Le Carre’s spy jargon is made up and none of his plots reflect anything but his imagination with the exception of TINKER TAILOR SOLDIER SPY, and even there he badly mishandles the Philby character’s psychology.

On the other hand many of the absurd plots in Fleming’s books are based on actual wartime incidents or plans, the colorful villains on real people, and Bond himself on any number of real agents — including one who used to tool around Paris in a Rolls Royce packing a gun (Wilfrid Dunderdale). Almost everyone would choose Le Carre as the more realistic of the two — and be wrong. But he does work to fake realism more consistently.

Even two of the greatest master criminals in fiction have real life counterparts: Moriarity was suggested by Adam Worth; and Dr. Fu Manchu the French fence Hanoi Shan. For that matter try Lawrence of Arabia purely as fiction.

Dr. Crippen is a pretty good example of the improbability of actual crime what with disguising his lover as a boy and being chased across the Atlantic by Inspector Dew racing to beat him to New York, and the whole thing playing out in the world press while Crippen was kept in the dark. I’m not sure even Christie could have made that one believable. Then throw in he was largely convicted on the evidence of Sir Bernard Spilsbury, a figure as improbable as any fictional detective, and most editors would toss it the outgoing slush pile.

That’s why in general if the writer entertains me I give him or her their improbabilities. If you don’t you could find fairly quickly you couldn’t read fiction at all. Of course some writers stretch my patience and abuse the honor system, but I tend to be lenient until they really mess up. After all that murderous orang-outang from the very first story in the genre is pretty improbable.

June 23rd, 2010 at 6:18 am

H. M. gradually became so monstrously willful as to become an impossible character. The last few books were so embarrassing it’s just as well Carr stopped the series. Fell never descended to that level. It’s not that Fell ruins the books for me–some of the best Carr books are Fell titles–it’s just he does nothing for me as a character (except maybe the locked room lecture or perhaps Crooked Hinge) and I find some of his mannerisms irritating. When I read one of the classics H.M.s, though, I’m always looking forward to what he will do next. In addition to being a great atmospheric horror writer, Carr was an accomplished humorous writer.

I first read Carr in my first year of law school on a gray blustery day on the balcony of an old gray apartment building in Chicago. It was The Burning Court. Carr at his best enchants you, there’s a magical quality to his writing. Rereading him I find myself noticing what I call Carrisms that I never even noticed the first time around. Something in me has changed a bit–maybe it’s all the slower-paced Britishers I’ve been reading, I don’t know. But I still enjoyed rereading him quite a bit.

On the whole I like him better than Sayers, for what that is worth (though I do think Harriet is believable as a character, in great part because she is an ego-projection of the author)! I found on rereading her that I didn’t like the antics of Lord Peter quite as much as I once did. And Carr’s plots are cleverer.

June 23rd, 2010 at 6:06 pm

What a fascinating conversation on JDC! But, on a minor point, John never met Chesterton. He did indeed base Dr. Fell on GKC, and some of Chesterton’s friends told Carr that GKC didn’t mind at all. Carr hoped to meet Chesterton when he was inducted into the Detection Club in 1936, but GKC died earlier that year.

June 23rd, 2010 at 8:16 pm

A minor point, maybe, Doug, but after 12 earlier comments, it’s something I really wanted to know. Thanks!

June 23rd, 2010 at 8:55 pm

I’m as surprised as anyone that this one went on so long! Doug: I thought I had read that in your book. Also, the bit about The Arabian Nights Mystery and Hamish Hamilton came from your book as well, of course. I think there are a few Carr reviews yet to post, it will be interesting to see how that goes. This Green Capsule one was the fourth, I think, after hew Who Whispers, The Man Who Could Not Shudder and The Corpse in the Waxworks.

June 24th, 2010 at 1:12 pm

I do wonder whether the reason that Carr ended up dropping HM was something to do with the need to constantly find him something to do. For all of his harrumphings and coughs and splutters, Fell is able to vanish into the background when necessary. He doesn’t need to take centre stage quite so often. HM is a much bigger and more comical personality, and Carr often provides him with big set-pieces (such as the Baseball game in A GRAVEYARD TO LET). HM needs to be centre stage much more than Fell for the book to work. As time wore on, perhaps Carr just felt that he had run out of things for HM to do. It’s a shame, really, for as much as I love Fell, HM is my favourite of Carr’s series characters.

June 24th, 2010 at 4:20 pm

I think it’s the mixture of the seriousness and silliness that I don’t like in Fell. I’d like him better as a mostly serious character (similarly I think Carr had softened Bencolin too much by the last book). With Merrivale I look forward to the humor bits. Although, yes, I think Carr ended up building Merrivale too much around “the bit” in each book. His behavior just got more and more outlandish–boorish really–until he became unacceptable. But I love some of the earlier bits, like the magic show in The Gilded Man.

Fell can recede–like In He Who Whispers. H. M. will not be contained.

June 24th, 2010 at 6:21 pm

Looking at the publication dates, it’s interesting to note that Fell is at his most Merrivale-like at the beginning of THE EIGHT OF SWORDS (1934)(His impersonation of the German psychiatrist, not to mention the stories about his time in the USA) That same year we see THE PLAGUE COURT MURDERS appear

June 24th, 2010 at 6:48 pm

I think Curt and Bradstreet have both hit on the essential problem in regard to H.M. and the relative restraint in regard to Fell. I like the ‘bits’ with H.M. for the most part, but they must have been a strain to come up with and make work in regard to the rest of the book. And I don’t think he ever knew who H.M. was in the same way he knew Fell. There is only one major change in Fell’s history from the first to last (he changes to a historian from his original career), but H.M. is all over the place (though his career as both doctor and barrister was also true of Freeman’s Thorndyke and the real Sir Bernard Spilsbury).

But it may be that the very looseness of H.M.’s conception allows for more inventiveness than the more fixed Fell. And while Churchill was certainly a part of H.M.’s persona early on his identification with the character grows more pronounced over time.

Re Bencolin the character in the early stories isn’t as dark as the one in the first three novels, and I think Carr tried to get back to that in the fourth book — too much so in my opinion. Notably, with the exception of Patrick Butler, all his later series sleuths tend to be on the portly and humorous side, even Colonels Marquis and March.

I like the dark and ‘cruel’ Bencolin, but I can see where Carr may have felt the need to get away from that, just as he tried something different with Patrick Butler in BELOW SUSPICION and PATRICK BUTLER FOR THE DEFENSE. In regard to Butler I don’t think he really pleased anyone but himself (and me, I enjoyed the character), and went back to his fallback — Fell and the historical books.

June 25th, 2010 at 1:37 pm

I really liked the Patrick Butler character, too. I read …FOR THE DEFENCE in one go, and thoroughly enjoyed it. Clever little mystery, and the romance really works. BELOW SUSPICION was also enjoyable. Shame that he didn’t carry on with the character.

June 30th, 2010 at 7:34 pm

[…] reviews he wrote as a result. The Problem of the Green Capsule was the fourth, and you can read it here. […]

June 4th, 2022 at 6:46 am

[…] Problem of The Green Capsule has been reviewed, among others, by Curtis Evans at Mystery File, Nick Fuller at The Grandest Game in the World, Martin Edwards at ‘Do You Write Under Your Own […]