Fri 2 Jul 2010

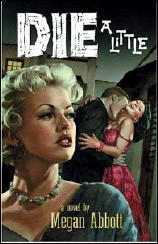

MEGAN ABBOTT – Die a Little. Simon & Schuster, hardcover, February 2005.

There are books that come along, every once in a while — in mystery fiction, that is — which belong almost in a category of their own. Die a Little, a first novel, is one of them.

It might be described as Southern Calilfornia “noir,” but if I were to say that, it would immediately bring someone like Raymond Chandler to mind, I’m sure. But while the milieu is the same — Los Angeles, Hollywood — brought up to date into the early 50s, rather than the 30s and 40s, this is a book that I can’t imagine Chandler ever having written.

The problem I’m facing right now is that “noir” is one of those words that means something different to almost everyone. To me it’s when a story is has a sense of darkness to it — well, yes, I know — a sense of desperation and/or despair. Woolrich is noir, and in a way, I can almost imagine that he could have written Die a Little. Almost.

“Noir” to me is a story that happens to everyday people. Everyday people, that is, who sometimes, not always, have a bit of shady side to them. They find themselves in situations in which they struggle to get to out, and all they do is find themselves more and more caught up in the webs that fate has trapped them in.

“Noir” is not everyday cheap thugs messing up their own lives in crummy, violent ways. “Noir” is not a private eye going about his everyday business, snooping into the business of others. “Noir” is not bizarre sex, the kinky stuff. Although, on the other hand — and this is important — any of these might be. It’s the tone, it’s the feeling, and it’s instinctive. I know it when I read it. And this book has it.

“Noir” from a female point of view. Megan Abbott is not the first woman to write noir, but no one, male or female, has used the female point of view in quite the same way before — that of fascination and frustration, worry and envy. Could Woolrich have written this book? Keep reading.

Lora King is a schoolteacher. Her brother Bill works for the L.A. district attorney’s office. They seem very close to each other, at least so far as the reader can tell from the way Lora tells the story. We never are privy to any of Bill’s thoughts, only Lora’s, and when Bill falls in love with — and marries — a victim of a minor automobile accident named Alice, it is, although she does not quite say this (although she does), it is as though her world has been turned upside down. And inside out.

Alice, shall we say, is flamboyant, glittery, coarse (in a refined way), loud, trashy, with a mysterious (or even worse, dishonorable) past, with uncouth (and couth) friends and associates, but mostly uncouth, as Lora quickly discovers — very much the opposite of the siblings Laura and Bill. Bill is enchanted, Lora is protective, and Lora (although she never says so) is fascinated. Alice is a someone who has lived. Bill and Lora, up to now, never have.

There is an eerie sense of mystery that envelops the three of them, so massively that at times there seems to be no room to breathe, for either the characters or the reader. When Lora goes with Alice to visit the latter’s friend Lois, Lora briefly eavesdrops on the other two when they do not know she is listening. From page 71, here is how she tells what happens:

The voice — as it seems only one now — becomes abruptly lower, inaudible, sliding from reach. The more I strain, the more I lose to the ambient sounds of the courtyard, the radio, a creaking chair, the cat, the vague clatter of someone knocking shoes together, a bottle rolling.

Lora begins to investigate Alice, her past, and the hold she has on her brother. From pages 110-111:

There is a string I am pulling together, a string a question marks so long they are beginning to clatter against each other, and loudly.

I count them on my fingers, beginning to feel the fool; the missing credentials, the unexplained absences, the playing card, the postcard, and now the address book. And perhaps most of all, Alice herself. Something in her. The hold so tight over my brother, and suddenly it appears more and more as thought she is this brooding darkness lurking around him, creeping toward him, swarming over him. Her glamour like some awful curse.

In a book like this, it is the men who are the fragile ones. Alice is obviously the strongest, most inscrutable, of the three, but Lora, as it turns out — but that would be telling.

Note: A shorter version of this review appeared in Historical Novels Review.

July 2nd, 2010 at 12:47 am

In its way. a sinister masterpiece. I found it unforgetable and terrific at giving the feel of 50s L.A.

I read it last year, raved about to my circle of friends.

I quickly ordered it on unabridged audio and it’s been just about time to give it a listen.

(I remember the plot and atmosphere clearly, but try to not listen to an audio book when I can still remember the actual phrasing…)

July 2nd, 2010 at 9:57 am

What a well-written review. Thanks for re-posting this. I have not read this book, though i have read others by the author and enjoyed them. You have sufficiently tweaked my interest this morning. Looks like my wallet will be slimmer soon, and my TBR Pile taller.

July 2nd, 2010 at 4:28 pm

Well, this did my heart good.

July 2nd, 2010 at 4:48 pm

Patti

I don’t know how Megan and I got together, whether I sent her the review, or somehow she saw it somewhere, but she did. There was a lag time between my reading it and when it appeared in the Historical Novels Review, but I had (and still have) an advance reading copy, and other than the big outfits like PUBLISHERS WEEKLY, I was among the first to review it.

Hope she remembers it! Say hi from me.

— Steve

July 2nd, 2010 at 4:58 pm

Megan Abbott taught an introductory course in hardboiled fiction at The New School in Manhattan in the Spring of 2006. The title of the course was “Kiss Me Deadly: Gender Play in Hardboiled Fiction.”

Just after the course started she sent me a syllabus for it

https://mysteryfile.com/Abbott/Syllabus.html

plus a PDF handout

https://mysteryfile.com/Abbott/Hardboiled.pdf

that she passed out the first evening describing the overall “geneaology” of hardboiled fiction, putting into perspective the books and authors to be covered in the course and to get some discussion started.

July 2nd, 2010 at 6:54 pm

First time I saw it, Steve and it’s nice reading it now. And one of the most interesting reviews of it five years later.

July 2nd, 2010 at 11:26 pm

It’s nice to know the true noir voice is alive and well. The cover alone was enough to sell me, but it never hurts when the book itself is this good.

July 3rd, 2010 at 5:55 am

Excellent review, Steve. Thanks.

July 9th, 2010 at 8:40 am

Megan Abbott writes noir better than any one publishing today!