Thu 29 Aug 2013

Archived Review: URSULA CURTISS – Catch a Killer (The Noonday Devil).

Posted by Steve under Authors , Reviews[8] Comments

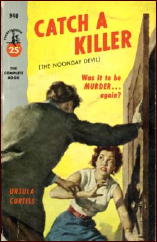

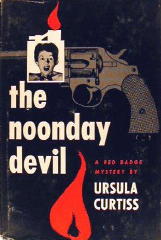

URSULA CURTISS – Catch a Killer. Pocket 940; 1st printing, June 1953. Hardcover edition: Dodd Mead, 1951, as The Noonday Devil.

It’s my guess that every time one of Ursula Curtiss’s books is reviewed today, it begins with the observation that her mother was mystery writer Helen Reilly, and that her sister was mystery writer Mary McMullen. (And equally obviously, I’m no exception.) It must have been in the genes, but during the time when all three were actively writing (Reilly from 1930 to 1962; Curtiss from 1948 to 1985, with a posthumous collection of short stories; and McMullen from 1951 to 1986), do you suppose that anyone ever asked them what was in the water they were drinking?

While Helen Reilly had a series detective who appeared in most of her books, Inspector McKee of Manhattan Homicide, Ursula Curtiss and Mary McMullen, were heavy practitioners of (suburban?) domestic malice and/or romantic suspense, and neither of them (as far as I know) used a repeating character in any of their books.

As far as Curtiss is concerned, this is the only book of hers I’ve read. So far. In any case, what you expect is not always what you get. In Catch a Killer, for example, I was surprised (although not nonplussed) to discover that the leading character is male, and that the story begins in Manhattan. I had the uneasy feeling that I was leaning one way, and the book, with Curtiss in charge, was going another.

In the second half of the book, though, the scene changes, and rather drastically. Under some pretext or another, all of the leading characters seem to find their way to the same small country town in New England, and when they do, everything seems to revert to normal. (By which I mean, closer to what was expected, if not anticipated.) And as a direct consequence, perhaps with the characters’ closer proximity to each other, the action seems to pick up as well.

The atmosphere is dark, introspective and moody throughout. And coincidences simply thrive in such climates, beginning as they do here, in Chapter One. When you walk into an unfamiliar bar for the first time, for example, you never know whom you’ll meet, and that’s where Andrew Sentry finds a man who had been in the same Japanese prison camp as his brother Nick – an encounter occurring only by chance.

Nick, as it happened, died in a fatal attempt to escape, and his death, Andrew for the first time is now told, was no accident. There was an informer – someone Nick knew. Someone who told their guards of Nick’s plans, which were then foiled. This is an unusual (if not unique) means of killing someone, but who was the mysterious man who called himself Sands, and what was his motive?

More coincidences. Every male in Andrew’s small circle of friends and acquaintances seems to have been a Japanese prisoner in the Philippines at some time or another during the war. Nick’s fiancée Sarah Devany may have received a postcard in code from him just before he died, but when a simple question might have unraveled the mystery before it has even begun, there are, unfortunately, barriers which, as it happens, have been laid in the way.

When Andrew came to break the news of Nick’s death to Sarah, it is revealed, he found her kissing another man, and he has not spoken to her since. And since the case for murder is so flimsy, the police cannot be called in, which limits Andrew’s resources to himself and whoever he feels he can trust, the list of whom changes chapter by chapter.

And so does the reader’s grip on the story, or vice versa, the story’s grip on the reader. Excellent characterizations are mixed helter-skelter with a plot that’s held together with a strong brand of duct tape. Nonetheless, New England summer towns can be filled with as much malice as large population centers such as Manhattan, and the generally capable touch of Ursula Curtiss goes a long way in proving it.

August 30th, 2013 at 1:17 am

I enjoyed this novel very much. I think it is one of her best suspense novels.

August 30th, 2013 at 1:47 am

I’m inclined to read it again myself, should my copy ever come to surface again!

August 30th, 2013 at 7:34 pm

Interesting. I’d like to know more about the whole family.

August 30th, 2013 at 8:34 pm

For a lot more on Helen Reilly’s career, see Michael Grost’s long article about her on the main Mystery*File website, followed by a complete bibliography and lots of cover imagess:

https://mysteryfile.com/Reilly/Grost.html

For more on the family, I should have remembered this link before now, an article about the family posted much earlier here on this blog:

https://mysteryfile.com/blog/?p=136

Thanks for the nudge, Kelly!

August 30th, 2013 at 8:39 pm

I’ve enjoyed the three or four Ursula Curtiss mystery novels I’ve read over the years. I haven’t read any Helen Reilly or Mary McMullen although I many have copies of their books floating around. There’s a new focus on women suspense writers. Here’s one of the latest books on this topic:

Troubled Daughters, Twisted Wives: Stories from the Trailblazers of Domestic Suspense [Penguin, $16.00], an anthology of 14 crime stories, all written by women in the 40s through 70s. Editor Sarah Weinmen selected tales from Patricia Highsmith, Joyce Harrington, and other writers who laid the groundwork for such modern bestsellers as Gillian Flynn and Tana French. Sarah Weinman is a news editor for Publishers Marketplace and Crime Wave columnist for the National Post Books section.

August 30th, 2013 at 8:47 pm

I saw that book in the local Barnes & Noble store yesterday, George, and I was so impressed that I almost bought it. But something in the back of my mind warned me that maybe I shouldn’t, and I was right.

When I got back home I discovered an email from Amazon telling me that the book was on its way to me. Turns out that I had pre-ordered it several months ago, but in the meantime I had all but forgotten it.

So I don’t have a copy now, but I will in a few days

September 1st, 2013 at 7:25 pm

I’ve never read any Ursula Curtiss.

This review makes her sound mighty interesting.

Have ordered The Noonday Devil through Inter Library Loan.

Thank you!

September 1st, 2013 at 8:55 pm

Mike

You’re welcome. I’m always happy to know when good books find their way to hands (and eyes) of those who will appreciate them.

— Steve