Sat 29 Mar 2014

Reviewed by Jonathan Lewis: GEORGES SIMENON – Pietr the Latvian.

Posted by Steve under Reviews[9] Comments

GEORGES SIMENON – Pietr the Latvian. Penguin Books, softcover, 2013. Translated from the French by David Bellos. First US edition: Covici Friede, hardcover, 1931. First UK edition: Hurst, hardcover, 1933. Also published as Maigret and the Enigmatic Lett. Penguin, US/UK, paperback, 1963. First published serially in French as Pietr-le-Letton in the weekly Ric & Rac, No. 71-83, 19 July to 11 October 1930.

Class-conscious interwar Paris, along with gritty Depression-era New York City and 1940s-era noir Los Angeles, are ideal urban settings for mystery writers seeking to place their protagonist in the heart of societies experiencing disruptive cultural and social changes.

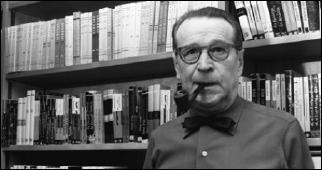

Georges Simenon’s (1903-1989) Pietr the Latvian, originally published in 1930, is a police procedural set primarily in interwar Paris. In this short novel, Simenon introduces the character of Inspector Maigret, one of the twentieth-century’s best-known fictional policemen. After this first Maigret novel, Simenon would go on to feature the pipe-smoking detective in in 74 additional novels and 28 short stories. (There were also numerous television adaptations.)

Is there a robust market for Maigret in the English-speaking world? Hard to say, but Penguin Books surely must have sensed a profitable business opportunity when it decided that Penguin Classics, beginning in 2013, would publish English translations of all the Inspector Maigret novels.

The first of the Maigret novels, Pietr the Latvian, both captivates and disappoints. The plot follows the Parisian inspector’s relentless pursuit of the eponymous international criminal. When Maigret discovers a man fitting Pietr’s description dead in a train car, the mystery only deepens. There appear to be two Pietrs, one dead and one still very much alive, residing in a Parisian hotel. Maigret’s chase takes him to unique locales within both Paris and Normandy. Along the way, he encounters a wide array of unique characters, including an American millionaire and his wife, a dancer, a Jewish hotelier, and a man who appears to be Pietr.

Simenon’s prose succeeds at temporarily transporting the reader to a wet, windswept land where things aren’t always what they seem. Two of the novel’s memorable settings are the posh Majestic, a hotel on the Champs-Élysées and the Marais, the traditional Jewish quarter. The contrast between these two worlds within the larger city of Paris, as described by Simenon, is palpable.

A notable subtext is the author’s critical analysis of the ethnic schisms and class divisions of interwar Paris. For instance, Simenon describes Inspector Maigret as both having a proletarian frame and being out of place at an elite Parisian hotel:

And when Inspector Maigret attends the opening night of a play at the Gymnase Theatre to trail a wealthy suspect, “he stuck out as the only person not wearing formal attire†(p. 56). Simenon’s descriptions, both explicit and implicit, of the mores of the trans-Atlantic upper crust also merit the reader’s attention.

Simenon’s treatment of the ethnic divide in Paris, namely between native Frenchmen and Eastern European immigrants, is also worth analyzing. The story hinges, in part, on how one Jewish female character from the Marais interacts with persons staying at the Majestic.

Through Simenon’s writing, one catches a glimpse of how many Western Europeans at the time viewed emigrants from Russia, Poland, and the Baltics as both foreign and mysterious. A contemporary reader may bristle upon reading Chapter 14’s opening line, one dealing with the aforementioned Jewish character’s apartment:

That said, Simenon’s treatment of Jewish and Eastern European characters is comparably innocuous when compared with much that was written in that era.

It’s too bad, then, that this good detective story with an atmospheric setting suffers from uneven writing, at least in this translation. There are far too many instances within the text where the writing can only be best described as clunky. The translation also seems to be too literal. (I say this as someone who has translated French academic texts.)

Take, for instance, this sentence from Chapter 12:

Or this sentence from Chapter 10:

Fortunately, not all of the work reads like this. It would be preferable to read sentences that not only captured Simenon’s original intent, but also flowed well in contemporary English. Simenon’s writing, or at least how it’s rendered here, is nowhere near as fluid as that of Arthur Conan Doyle or Raymond Chandler.

With all that in mind, it’s worth mentioning that this will not be the only Inspector Maigret novel I shall read. I look forward to reading other translators’ rendering of Simenon’s work and to follow the life and times of one of the twentieth-century’s most beloved fictional detectives.

March 29th, 2014 at 8:37 am

Good one. It almost makes me want to go back and start reading the series again, perhaps because today will be the same kind of cold, rainswept day Simenon wrote about so often and so well.

March 29th, 2014 at 9:20 am

This is quite an ambitious project Penguin is doing. With 75 Maigret novels to publish, at a rate of one a month and perhaps in chronological order, you can do the math yourself.

March 30th, 2014 at 10:15 am

I have a lot of Maigret novels in a box in the cellar. But I have read only ten or twelve of them. Furtheron I enjoyed Maigret graphic novels and the TV-series with Rupert Davis.

March 31st, 2014 at 4:05 pm

Simenon likely would never have come to this country if Gertrude Stein hadn’t introduced the Maigret novels to Ernest Hemingway. His mentions of them would eventually open the American audience, and of course the time Simenon lived in Arizona (next door to John Creasey more or less)and produced a number of American set novels (The Brothers Rico, Bottom of the Bottle) would finally impress Maigret on the American psyche.

I don’t recall Simenon having much of an American following until the fifties, and Maigret until almost the sixties (I think Ace may have issued the first Maigret in American paperback though it could have been Bantam’s Maigret in New York or Maigret and the Strangled Stipper.

The Brits tumbled to Simenon fairly early and were for a long time the only source for Maigret in English. As far as I know all translations of his work are British, and British centric in many small details (Maigret is Commissar not an Inspector, Inspector isn’t used in France). Why no one at least Americanized the translations I can’t imagine, but as far as I know many of these volumes are the original translations from their first publication.

For a different view of Maigret read Simenon’s Maigret in Court, which gives up a picture of the younger Maigret as a gendarme.

Incidentally the famous Surete is only the detective branch of the Paris police, not a national police force. The national police are the Police Judiciaire known as the PJ and Nicholas Freeling’s Henri Castang provides a fine picture of their work. In the past the Surete did provide help to smaller areas in France much as Scotland Yard (the detective branch of the London Metropolitan Police) did. Americans to this day seem to believe both are equivalent to the FBI.

April 1st, 2014 at 5:33 am

This excellent provocative review makes me think you might enjoy Bill Alder’s work:

Maigret, Simenon and France: Social Dimensions of the Novels and Stories

The Maigret series in general “both captivates and disappoints†me, which is probably why I’ve read the bulk of it.

Having dabbled in translating French to English (Le Docteur Maigret to Doctor Maigret), I worry about the “clunky†translation you describe. It will be interesting to read what you think of the forthcoming translations. I get the sense Penguin will be calling on several to many for the job.

Thanks!

April 1st, 2014 at 9:10 pm

David,

Thanks for the fascinating information re Scotland Yard and Police Judiciaire. I am one of those Americans who did not know the deal.

April 4th, 2014 at 9:54 am

It looks like Penguin will be releasing one Simenon novel per month. I plan to read and review another one in the near future

November 23rd, 2014 at 2:43 pm

I quite enjoyed the book, but really it was a messy read, made even more complicated by all that East European baloney. and all those exclamation marks! Often ending consecutive sentences! Why couldnt the people who sent the telegrams in the first paragraphs come round sooner, and identify Pietr before poor Maigret stopped a bullet? and all Latvian men’s names end in s, so it was actually Pietrs the Latvian. But very atmospheric, i caught a bad cold while reading it.

May 12th, 2023 at 3:43 am

[…] Mystery*File […]